Arachnid

| Arachnid Temporal range:

Early Silurian – present | |

|---|---|

| |

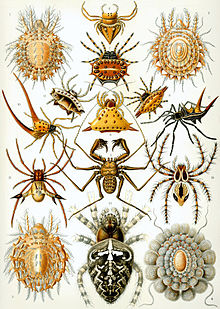

| Representatives of the 12 extant orders of arachnids | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Clade: | Arachnomorpha |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Class: | Arachnida Lamarck , 1801

|

| Orders | |

| |

Arachnids are arthropods in the class Arachnida (/əˈræknɪdə/) of the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, harvestmen, camel spiders, whip spiders and vinegaroons.[1]

Adult arachnids have eight legs attached to the cephalothorax, although the frontmost pair of legs in some species has converted to a sensory function, while in other species, different appendages can grow large enough to take on the appearance of extra pairs of legs. The term is derived from the Greek word ἀράχνη (aráchnē, 'spider'), from the myth of the hubristic human weaver Arachne, who was turned into a spider.[2]

Almost all

Morphology

Arachnids are further distinguished from insects by the fact they do not have

Like all arthropods, arachnids have an exoskeleton, and they also have an internal structure of cartilage-like tissue, called the endosternite, to which certain muscle groups are attached. The endosternite is even calcified in some Opiliones.[15]

Locomotion

Most arachnids lack

Physiology

There are characteristics that are particularly important for the terrestrial lifestyle of arachnids, such as internal respiratory surfaces in the form of

Further adaptations to terrestrial life are

The excretory glands of arachnids include up to four pairs of

Arachnid blood is variable in composition, depending on the mode of respiration. Arachnids with an efficient tracheal system do not need to transport oxygen in the blood, and may have a reduced circulatory system. In scorpions and some spiders, however, the blood contains

Diet and digestive system

Arachnids are mostly

Arachnids produce digestive enzymes in their stomachs, and use their pedipalps and chelicerae to pour them over their dead prey. The digestive juices rapidly turn the prey into a broth of nutrients, which the arachnid sucks into a pre-buccal cavity located immediately in front of the mouth. Behind the mouth is a muscular, sclerotised

The stomach is tubular in shape, with multiple

Senses

Arachnids have two kinds of eyes: the lateral and median

In addition to the eyes, almost all arachnids have two other types of sensory organs. The most important to most arachnids are the fine sensory hairs that cover the body and give the animal its sense of touch. These can be relatively simple, but many arachnids also possess more complex structures, called trichobothria.

Finally, slit sense organs are slit-like pits covered with a thin membrane. Inside the pit, a small hair touches the underside of the membrane, and detects its motion. Slit sense organs are believed to be involved in proprioception, and possibly also hearing.[21]

Reproduction

Arachnids may have one or two gonads, which are located in the abdomen. The genital opening is usually located on the underside of the second abdominal segment. In most species, the male transfers sperm to the female in a package, or spermatophore. The males in harvestmen and some mites have a penis.[34] Complex courtship rituals have evolved in many arachnids to ensure the safe delivery of the sperm to the female.[21] Members of many orders exhibit sexual dimorphism.[35]

Arachnids usually lay yolky

Taxonomy and evolution

Phylogeny

The

| Arthropoda

|

| ||||||||||||

The extant chelicerates comprise two marine groups: Sea spiders and horseshoe crabs, and the terrestrial arachnids. These have been thought to be related as shown below.[40][43] (Pycnogonida (sea spiders) may be excluded from the chelicerates, which are then identified as the group labelled "Euchelicerata".[45]) A 2019 analysis nests Xiphosura deeply within Arachnida.[46]

| Chelicerata |

| ||||||||||||

Discovering relationships within the arachnids has proven difficult as of March 2016[update], with successive studies producing different results. A study in 2014, based on the largest set of molecular data to date, concluded that there were systematic conflicts in the phylogenetic information, particularly affecting the orders

|

Arachnopulmonata |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

More recent phylogenomic analyses that have densely sampled both genomic datasets and morphology have supported horseshoe crabs as nested inside Arachnida, suggesting a complex history of terrestrialization. but recover other ordinal relationships with low support.

Fossil history

The Uraraneida are an extinct order of spider-like arachnids from the Devonian and Permian.[58]

A fossil arachnid in 100 million year old (mya)

Taxonomy

The subdivisions of the arachnids are usually treated as orders. Historically, mites and ticks were treated as a single order, Acari. However, molecular phylogenetic studies suggest that the two groups do not form a single clade, with morphological similarities being due to convergence. They are now usually treated as two separate taxa – Acariformes, mites, and Parasitiformes, ticks – which may be ranked as orders or superorders. The arachnid subdivisions are listed below alphabetically; numbers of species are approximate.

- Extant forms

- Acariformes – mites (32,000 species)

- Amblypygi – "blunt rump" tail-less whip scorpions with front legs modified into whip-like sensory structures as long as 25 cm or more (250 species)

- Araneae – spiders (51,000 species)

- Opiliones – phalangids, harvestmen or daddy-long-legs (6,700 species)

- Palpigradi – microwhip scorpions (130 species)

- Parasitiformes – ticks (12,000 species)

- Pseudoscorpionida – pseudoscorpions (4,000 species)

- Ricinulei – ricinuleids, hooded tickspiders (100 species)

- Schizomida – "split middle" whip scorpions with divided exoskeletons (350 species)

- Scorpiones – scorpions (2,700 species)

- Solifugae – solpugids, windscorpions, sun spiders or camel spiders (1,200 species)

- Uropygi (also called Thelyphonida) – whip scorpions or vinegaroons, forelegs modified into sensory appendages and a long tail on abdomen tip (120 species)

- Extinct forms

- †Haptopoda – extinct arachnids apparently part of the Tetrapulmonata, the group including spiders and whip scorpions (1 species)

- †Phalangiotarbida – extinct arachnids of uncertain affinity (30 species)

- †Trigonotarbida – extinct (late Silurian Early Permian)

- †spinnerets(2 species)

It is estimated that 110,000 arachnid species have been described, and that there may be over a million in total.[4]

See also

- Arachnophobia

- Endangered spiders

- Glossary of spider terms

- List of extinct arachnids

References

- ^ Cracraft, Joel & Donoghue, Michael, eds. (2004). Assembling the Tree of Life. Oxford University Press. p. 297.

- ^ "Arachnid". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). 1989.

- ISBN 9783319591568.

- ^ .

- ISBN 978-1-4822-3582-1.

- ISBN 978-3-89432-405-6.

- S2CID 90899467.

- ISBN 978-981-10-1594-6.

- ISBN 978-0-7641-3885-0.

- ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ISBN 978-0-521-25218-8.

- ISBN 978-0-674-02343-7.

- PMID 29783957.

- .

- S2CID 23119386.

- ^ S2CID 40503319.

- S2CID 46935000.

- ISSN 1477-9145. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- S2CID 56461501.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-0-03-056747-6.

- S2CID 246078291.

- S2CID 234364795.

- ^ Common harvestman | The Wildlife Trusts

- ^ How do harvestmen hunt? - BBC Wildlife Magazine

- ^ ISBN 978-0-674-02343-7.

- ^ Rare Vegetarian Spider Discovered

- PMID 29783636.

- PMID 22540028.

- PMID 35448857.

- PMID 28797246.

- PMID 34118237.

- ^ Tick Paralysis - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf

- PMID 30416880.

- PMID 30416880.

- ISBN 978-1-4557-3356-9.

- S2CID 73728615.

- S2CID 53166528.

- PMID 20534705.

- ^ S2CID 4427443.

- ^ PMID 20702459.

- PMID 21896763.

- ^ PMID 25107551.

- PMID 24077329.

- S2CID 4431635.

- ^ PMID 30917194.

- S2CID 231614575.

- PMID 35440674.

- ^

Ontano, A.Z.; Gainett, G.; Aharon, S.; Ballesteros, J.A.; Benavides, L.R.; Corbett, K.F.; et al. (June 2021). "Taxonomic sampling and rare genomic changes overcome long-branch attraction in the phylogenetic placement of Pseudoscorpions". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 38 (6): 2446–2467. PMID 33565584.

- PMID 32385269.

- PMID 31847768.

- PMID 35137183.

- ^ S2CID 4239867.

- PMID 28431496.

- PMID 27030415.

- PMID 25405073.

- .

- PMID 19104044

- ^ Briggs, Helen (5 February 2018). "'Extraordinary' fossil sheds light on origins of spiders". BBC. Retrieved 9 June 2018.