Asama-class cruiser

Asama in 1900

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Asama class |

| Builders | Armstrong Whitworth, United Kingdom |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | Izumo class |

| Built | 1897–1899 |

| In commission | 1899–1945 |

| Completed | 2 |

| Scrapped | 2 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Armored cruiser |

| Displacement | 9,514–9,557 long tons (9,667–9,710 t) |

| Length | 442 ft 0 in (134.72 m) (o/a) |

| Beam | 67 ft 2 in (20.48 m) |

| Draft | 24 ft 3 in – 24 ft 5 in (7.4–7.43 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 10,000 nmi (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 676 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

The Asama-class cruisers (浅間型装甲巡洋艦, Asama-gata sōkōjun'yōkan) were a pair of

Asama continued to make training cruises until she ran aground again in 1935, after which she became a stationary

Background and design

The 1896 Naval Expansion Plan was made after the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95 and included four armored cruisers in addition to four more battleships, all of which had to be ordered from foreign shipyards as Japan lacked the capability to build them itself. Further consideration of the Russian building program caused the IJN to believe that the battleships ordered under the original plan would not be sufficient to counter the Imperial Russian Navy. Budgetary limitations prevented ordering more battleships and the IJN decided to expand the number of more affordable armored cruisers to be ordered from four to six ships. The revised plan is commonly known as the "Six-Six Fleet".[1] These ships were purchased using the £30,000,000 indemnity paid by China after losing the First Sino-Japanese War.[2] Unlike most of their contemporaries which were designed for commerce raiding or to defend colonies and trade routes, these cruisers was intended as fleet scouts and to be employed in the battleline.[3]

In June 1896, Sir Andrew Noble, then in Japan, telegraphed Armstrong Whitworth to lay down two stock cruisers. Work then began on a preliminary design based on an improved version of the earlier Chilean cruiser O'Higgins. Several iterations of the design were made before the IJN approved the final design on 21 August. This was over 1,000 long tons (1,016 t) larger, more heavily armed, and slightly faster the Chilean armored cruiser.[4] The first ship of the class was laid down in October although the Japanese did not order the ships until 6 July 1897.[5]

Description

The ships were 442 feet 0 inches (134.72 m) long

The Asama-class ships had two 4-cylinder

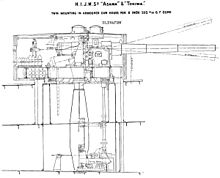

Armament

The

The

The Asama-class ships were equipped with five submerged 18-inch (457 mm)

Protection

All of the "Six-Six Fleet" armored cruisers used the same armor scheme with some minor differences, with the Asama class using Harvey armor. The waterline belt ran the full length of the ships and its thickness varied from 7.0 inches (178 mm) amidships to 3.5 inches (89 mm) at the bow and stern. The thickest part of the belt covered the middle of the ship for a length of 284 feet 2 inches (86.62 m). It had a height of 7 feet 0 inches (2.13 m), of which 4 feet 11 inches to 5 feet 0 inches (1.51 to 1.52 m) was normally underwater. The upper strake of belt armor was 5.0 inches (127 mm) thick and extended from the upper edge of the waterline belt to the main deck. It extended 214 feet 8 inches (65.42 m) from the forward to the rear barbette. The Asama-class ships had a single transverse 5-inch armored bulkhead that closed off the forward end of the central armored citadel.[15]

The barbettes, gun turrets and the front of the casemates were all 6 inches thick while the sides and rear of the casemates were protected by 51 millimeters (2.0 in) of armor.

Ships

| Ship | Builder[9] | Laid down[9]

|

Launched[16] | Completed[5] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asama | Elswick

|

20 October 1896 | 22 March 1898 | 8 February 1899 |

| Tokiwa | 6 January 1897 | 6 July 1898 | 18 April 1899 |

Service

Before the start of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904, Tokiwa supported Japanese forces during the

Russo-Japanese War

At the beginning of the Russo-Japanese War the sisters were assigned to the 2nd Division of the

In early March Tokiwa was reassigned to the 3rd Division and Asama joined her shortly afterwards.[22] They participated in the action of 13 April when Tōgō successfully lured out two battleships of the Russian Pacific Squadron. During this action, the sisters engaged the Russian cruisers that preceded the battleships before falling back on Tōgō's battleships.[23] When the Russians spotted the five battleships of the 1st Division, they turned back for Port Arthur and the battleship Petropavlovsk struck a minefield laid by the Japanese the previous night. The ship sank in less than two minutes after one of her magazines exploded.[24]

Tokiwa rejoined the 2nd Division a few days later and the division was tasked to contain the Russian armored cruisers based at Vladivostok. It failed to do so until 13 August[25] when the latter tried to rendezvous with the ships that attempted to breakout from Port Arthur. Unbeknownst to the Russians, Tōgō had defeated the ships from Port Arthur during the Battle of the Yellow Sea on 10 August and the Russian squadron from Vladivostok was intercepted off Ulsan, Korea by the 2nd Division. The steering of the Russian cruiser Rurik was damaged early in the battle and the Russians made several attempts to prevent the Japanese from concentrating fire on her, but were ultimately forced to abandon her to her fate. Kamimura left Rurik to the tender ministrations of his reinforcements and pursued the two remaining Russian ships for a time before breaking off pursuit prematurely based on an incorrect report that his flagship had expended most of her ammunition. Tokiwa only suffered three men wounded during the battle.[26]

In the meantime, Asama remained on blockade duty off Port Arthur and participated in a minor way in the Battle of the Yellow Sea. She was coaling when the Pacific Squadron sortied and took some time to intercept the Russian ships. The battle was almost over by then and the ship only engaged them for the last hour or so of the battle.[27] After the battle, the sisters were refitted and assigned to different units, escorting troop convoys to northern Korea and blockading the Tsugaru Strait until the Russian ships from the Baltic Fleet approached Japan in mid-1905.[28]

Battle of Tsushima

The Russian 2nd and 3rd Pacific Squadrons were spotted on the morning on 27 May 1905 and Tōgō ordered his ships to put to sea. Asama and Tokiwa were assigned to the 2nd Division in anticipation of this battle and Kamimura's ships confirmed the initial spotting later that morning before joining Tōgō's battleships. Together with most of the Japanese battleships, the division opened fire at 14:10 on the Russian battleship Oslyabya. Shortly afterwards, Asama was damaged by a shell that knocked out her steering that forced her to fall out of formation. Around 15:35, the Russian battleship Knyaz Suvorov suddenly appeared out of the mist at short range. Kamimura's ships engaged her for five minutes before she disappeared back into the mists. Asama rejoined the division at 15:50, but further hits caused serious flooding that again caused her to fall out of formation about 20 minutes later. She finally caught up to the division at 17:05. Shortly afterwards, Kamimura led his division in a fruitless pursuit of some of the Russian cruisers around 17:30. He abandoned his chase around 18:03 and encountered the Russian battleline about a half-hour later. He stayed at long range and his ships fired when practicable before ceasing fire at 19:30.[29]

The surviving Russian ships were spotted the next morning and the Japanese ships opened fire and stayed beyond the range at which the Russian ships could effectively reply. Rear Admiral

Subsequent service

In 1910–11 and 1914, Asama served as a training ship, making cruises with naval cadets to North and Central American and Hawaii, among other destinations. After the start of World War I in August 1914, she was assigned to search for Vice Admiral

While entering Puerto San Bartolomé in Baja California in early 1915, Asama struck an uncharted rock and was badly damaged. It took months to refloat her and to make her partially seaworthy. The ship was given temporary repairs at the British naval base at Esquimalt, British Columbia, before arriving back in Japan in December[35] where permanent repairs were not completed until March 1917.[32] Asama was assigned to the Training Squadron later that year and made another cadet training cruise in 1918.[36]

Tokiwa supported Japanese forces during the

Asama made a training cruise in 1921[36] before her armament was modified in 1922. All of her main deck guns, six 6-inch and four 12-pounder guns, were removed and their casemates plated over. In addition all of her QF 2.5-pounder guns were removed and a single 8 cm/40 3rd Year Type AA gun was added.[40] After the refit, she resumed her training cruises, generally at two-year intervals, until she ran aground in 1935. The damage to her bottom was severe enough that the IJN decided make her a stationary training ship in 1938.[41]

Tokiwa's

The Pacific War

The ship returned home in 1943 and began to lay defensive minefields in 1944. She was moderately damaged by a mine in April 1945 and struck an American mine two months later. By this time, her armament had been augmented with approximately ten 25 mm Type 96 AA guns in single mounts and 80

Asama was reclassified as a training ship in 1942 and became a gunnery training ship later that year. She was disarmed at some point during the war, only retaining several 8 cm/40 3rd Year Type anti-aircraft guns.[47] The ship survived the war intact and she and Tokiwa were stricken from the navy list in November 1945. Asama was scrapped in 1946–47 while Tokiwa was refloated in 1947 and scrapped that same year.[42][48]

Notes

- ^ "Cwt" is the abbreviation for hundredweight, 12 cwt referring to the weight of the gun.

Footnotes

- ^ Evans & Peattie, pp. 57–62

- ^ Brook 1999, p. 125

- ^ Milanovich, p. 72

- ^ Brook 1999, pp. 107–09

- ^ a b Milanovich, p. 73

- ^ Milanovich, pp. 74, 80

- ^ a b c d Jentschura, Jung & Mickel, p. 72

- ^ Milanovich, p. 81

- ^ a b c d e f Brook 1999, p. 109

- ^ Milanovich, pp. 76–77

- ^ a b Milanovich, p. 78

- ^ Friedman, p. 276; Milanovich, p. 78

- ^ Friedman, p. 114

- ^ a b Milanovich, p. 80

- ^ Milanovich, pp. 80–81

- ^ a b c Chesneau & Kolesnik, p. 225

- ^ Brook 1999, p. 107

- ^ Dix, p. 307

- ^ Kowner, p. 465

- ^ Warner & Warner, pp. 188–95

- ^ Forczyk, pp. 42–43

- ^ Corbett, I, pp. 127, 142

- ^ Warner & Warner, pp. 236–38

- ^ Forczyk, pp. 45–46

- ^ Corbett, I, pp. 188–89, 191–96, 283–89, 319–25, 337–51

- ^ Brook 2000, pp. 43, 45

- ^ Corbett, I, pp. 389, 397–98, 417

- ^ Corbett 1994, II, pp. 47, 52, 97, 104, 153, 159–60, 176–77, 217

- ^ Campbell 1978, Part 2, pp. 128–32; Part 3, pp. 186–87

- ^ Corbett 1994, II, pp. 319–20

- ^ a b Campbell 1978, Part 4, p. 263

- ^ a b Brook, p. 110

- ^ Watts & Gordon, p. 109

- ^ Corbett, II, pp. 356, 363–65, 377–80

- ^ a b Estes

- ^ a b Lacroix & Wells, p. 657

- ^ Burdick, pp. 235, 241

- ^ Saxon

- ^ Campbell 1985, pp. 197–98

- ^ Jentschura, Jung & Mickel, p. 73

- ^ Lacroix & Wells, pp. 657–59

- ^ a b c d Hacket & Kingsepp

- ^ Chesneau, p. 207

- ^ Campbell 1985, p. 200

- ^ Rohwer, p. 123

- ^ Fukui, p. 13

- ^ Fukui, p. 53

- ^ Lacroix & Wells, p. 659

References

- Brooke, Peter (1999). Warships for Export: Armstrong Warships 1867–1927. Gravesend: World Ship Society. ISBN 0-905617-89-4.

- Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-459-4.

- Campbell, N.J.M. (1978). "The Battle of Tsu-Shima, Parts 2, 3 and 4". In Preston, Antony (ed.). Warship. Vol. II. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 127–35, 186–192, 258–65. ISBN 0-87021-976-6.

- Chesneau, Roger, ed. (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. Greenwich, UK: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-146-7.

- Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- ISBN 1-55750-129-7.

- Dix, Charles Cabry (1905). The World's Navies in the Boxer Rebellion (China 1900). London: Digby, Long & Co. p. 307. OCLC 5716842.

- Estes, Donald H. (1978). "Asama Gunkan: The Reappraisal of a War Scare". Journal of San Diego History. 24 (3). Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- Evans, David & ISBN 0-87021-192-7.

- Forczyk, Robert (2009). Russian Battleship vs Japanese Battleship, Yellow Sea 1904–05. Botley, UK: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-330-8.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Hackett, Bob & Kingsepp, Sander (24 December 2011). "IJN Tokiwa: Tabular Record of Movement". FUSETSUKAN! Stories and Battle Histories of the IJN's Minelayers. Combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- Halpern, Paul S. (1994). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Hirama, Yoichi (2004). "Japanese Naval Assistance and its Effect on Australian-Japanese Relations". In Phillips Payson O'Brien (ed.). The Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 1902–1922. London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 140–58. ISBN 0-415-32611-7.

- Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter & Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 0-87021-893-X.

- ISBN 978-0-81084-927-3.

- Lacroix, Eric & Wells, Linton (1997). Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-311-3.

- Milanovich, Kathrin (2014). "Armored Cruisers of the Imperial Japanese Navy". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2014. London: Conway. ISBN 978-1-84486-236-8.

- Newbolt, Henry (1996). Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents. Vol. IV (reprint of the 1928 ed.). Nashville, Tennessee: Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-253-5.

- ISBN 1-59114-119-2.

- Saxon, Timothy D. (Winter 2000). "Anglo-Japanese Naval Cooperation, 1914–1918". Naval War College Review. LIII (1). Naval War College Press. Archived from the original on 13 December 2006.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Warner, Denis & Warner, Peggy (2002). The Tide at Sunrise: A History of the Russo-Japanese War, 1904–1905 (2nd ed.). London: Frank Cass. ISBN 0-7146-5256-3.

- Watts, Anthony J. & Gordon, Brian G. (1971). The Imperial Japanese Navy. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0385012683.