Izumo-class cruiser

A postcard of Iwate at speed, circa 1905–1915

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Izumo class |

| Builders | Armstrong Whitworth, United Kingdom |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Asama class |

| Succeeded by | Yakumo |

| Built | 1898–1901 |

| In commission | 1900–1945 |

| Completed | 2 |

| Lost | 2 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Armored cruiser |

| Displacement | 9,423–9,503 t (9,274–9,353 long tons) |

| Length | 132.28 m (434 ft) (o/a) |

| Beam | 20.94 m (68 ft 8 in) |

| Draft | 7.21–7.26 m (23 ft 8 in – 23 ft 10 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 2 shafts; 2 triple-expansion steam engines |

| Speed | 20.75 knots (38.43 km/h; 23.88 mph) |

| Range | 7,000 nmi (13,000 km; 8,100 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 672 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

The Izumo-class cruisers (出雲型装甲巡洋艦, Izumo-gata sōkōjun'yōkan) were a pair of

Iwate was first used as a

Background and design

Japan initiated the 1896 Naval Expansion Plan after the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95. The plan included four armored cruisers and four battleships, all of which had to be ordered from foreign shipyards as Japan lacked the capability to build them itself. Further consideration of the Russian building program caused the IJN to believe that the battleships ordered under the original plan would not be sufficient to counter the Imperial Russian Navy. Budgetary limitations prevented ordering more battleships and the IJN decided to expand the number of more affordable armored cruisers to be ordered from four to six ships. The revised plan is commonly known as the "Six-Six Fleet".[1] These ships were purchased using the £30,000,000 indemnity paid by China after losing the First Sino-Japanese War.[2] Unlike most of their contemporaries, which were designed for commerce raiding or to defend colonies and trade routes, the Izumo class was intended as fleet scouts and to be employed in the battleline.[3]

Construction of the Izumo-class ships was awarded to the

Description

The Izumo-class ships were 132.28 meters (434 ft 0 in) long

The ships had two 4-cylinder

Armament

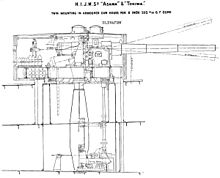

The

The

The Izumo-class ships were equipped with four submerged 18-inch (457 mm) torpedo tubes, two on each broadside. The Type 30 torpedo had a 100-kilogram (220 lb) warhead and three range/speed settings: 870 yards (800 m) at 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph), 1,100 yards (1,000 m) at 23.6 knots (43.7 km/h; 27.2 mph) or 3,300 yards (3,000 m) at 14.2 knots (26.3 km/h; 16.3 mph).[14]

Protection

All of the "Six-Six Fleet" armored cruisers used the same armor scheme with some minor differences, one of which was that the four later ships all used

The barbettes, gun turrets and the front of the casemates were all 6 inches thick while the sides and rear of the casemates were protected by 51 millimeters (2.0 in) of armor. The deck was 63 millimeters (2.5 in) thick and the armor protecting the

Ships

| Ship | Builder [9] | Laid down[9]

|

Launched[9] | Completed [17] | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Izumo | Armstrong Whitworth, Elswick | 14 May 1898 | 19 September 1899 | 25 September 1900 | Sunk, 28 July 1945; broken up, 1947[18] |

| Iwate | 11 November 1898 | 29 March 1900 | 18 March 1901 | Sunk, 25 July 1945; scrapped, 1946–1947[19] |

Service

Russo-Japanese War

The sisters spent most of the Russo-Japanese War as flagships together in the 2nd Division of the

In April 1904, the division was tasked to contain the Russian armored cruisers based at

Battle of Tsushima

The Russian 2nd and 3rd Pacific Squadrons were spotted on the morning on 27 May 1904 and Tōgō ordered his ships to put to sea. Izumo and Iwate had rejoined the 2nd Division in anticipation of this battle and Kamimura's ships confirmed the initial spotting later that morning before joining Tōgō's battleships. Together with most of the Japanese battleships, the division opened fire at 14:10 on the Russian battleship Oslyabya, which was forced to fall out of formation at 14:50 and sank 20 minutes later. After a failed torpedo attack was repulsed by Iwate and several other cruisers around the same time, the Russian battleship Knyaz Suvorov suddenly appeared out of the mist at 15:35 at short range. Kamimura's ships engaged her for five minutes before she disappeared back into the mists. Later in the day, Kamimura led his division in a fruitless pursuit of some of the Russian cruisers around 17:30. He abandoned his chase around 18:03 and encountered the Russian battleline about a half hour later. He stayed at long range and his ships fired when practicable before ceasing fire at 19:30.[24]

The surviving Russian ships were spotted the next morning and the Japanese ships opened fire and stayed beyond the range at which the Russian ships could effectively reply. Rear Admiral

Subsequent service

Izumo was ordered to patrol the west coast of

Iwate played a minor role in the war, participating in the

In 1924, four of the ships' 12-pounder guns were removed, as were all of their QF 2.5-pounder guns, and a single 40-caliber

China service and World War II

In 1932, during the

Still in Shanghai at the beginning of the Pacific War on 8 December 1941, Izumo captured the American river gunboat USS Wake and assisted in sinking the British river gunboat HMS Peterel.[18][36] On 31 December, the cruiser struck a mine in Lingayen Gulf while supporting Japanese forces during the Philippines Campaign. During this period, Iwate was still serving as a training ship in home waters. The sisters were briefly re-classified as 1st-class cruisers on 1 July 1942[18][19] before they became training ships in 1943. Izumo returned to Japan late that year and joined her sister in training naval cadets.[37]

In early 1945, the sisters were rearmed when their 8-inch guns were replaced by four

The sisters were attacked, but not hit, during the American aerial

Notes

- ^ "Cwt" is the abbreviation for hundredweight, 12 cwt referring to the weight of the gun.

Footnotes

- ^ Evans & Peattie, pp. 57–62

- ^ Brook 1999, p. 125

- ^ Milanovich, p. 72

- ^ Brook 1999, pp. 112–13

- ^ Milanovich, pp. 74–76

- ^ Milanovich, pp. 74, 80

- ^ a b c Jentschura, Jung & Mickel, p. 74

- ^ Milanovich, p. 81

- ^ a b c d Brook 1999, p. 112

- ^ Milanovich, pp. 76–77

- ^ a b Milanovich, p. 78

- ^ Friedman, p. 276; Milanovich, p. 78

- ^ Friedman, p. 114

- ^ a b Milanovich, p. 80

- ^ Milanovich, pp. 80–81

- ^ Chesneau & Kolesnik, p. 225

- ^ Milanovich, p. 73

- ^ a b c d e f Hackett & Kingsepp, Izumo

- ^ a b c Hackett & Kingsepp, Iwate

- ^ Kowner, pp. 241, 465

- ^ Forczyk, pp. 42–43

- ^ Brook 2000, pp. 43, 45

- ^ Corbett 1994, II, pp. 52, 104, 159–62, 176–77

- ^ Campbell 1978, Part 2, pp. 128–32; Part 3, pp. 186–87

- ^ a b Corbett 1994, II, pp. 319–20

- ^ Brook 1999, p. 113; Campbell 1978, Part 4, p. 263

- ^ Corbett, II, pp. 356, 363–65, 377–80

- ^ "Japanese Cruiser Sent to Mexico". San Francisco Call. California Digital Newspaper Collection. 12 November 1913. p. 2. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ Estes

- ^ Burdick, pp. 228, 241

- ^ Corbett 1938, I, pp. 366, 409

- ^ Lacroix & Wells, pp. 657–58

- ^ a b Chesneau, p. 174

- ^ Campbell 1985, pp. 197–98

- ^ "Japanese Consulate in Ruins". The Sydney Morning Herald. Trove. 18 August 1937. p. 15. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ Rohwer, p. 123

- ^ a b Fukui, p. 4

- ^ Campbell 1985, pp. 192–93

- ^ Campbell 1985, p. 200

References

- Brook, Peter (2000). "Armoured Cruiser vs. Armoured Cruiser: Ulsan 14 August 1904". In Preston, Antony (ed.). Warship 2000–2001. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-791-0.

- Brook, Peter (1999). Warships for Export: Armstrong Warships 1867–1927. Gravesend: World Ship Society. ISBN 0-905617-89-4.

- Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-459-4.

- Campbell, N.J.M. (1978). "The Battle of Tsu-Shima, Parts 2, 3 and 4". In Preston, Antony (ed.). Warship. Vol. II. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 127–35, 186–192, 258–65. ISBN 0-87021-976-6.

- Chesneau, Roger, ed. (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. Greenwich, UK: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-146-7.

- Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- ISBN 1-55750-129-7.

- Corbett, Julian (March 1997). Naval Operations to the Battle of the Falklands. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. Vol. I (2nd, reprint of the 1938 ed.). London and Nashville, Tennessee: Imperial War Museum and Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-256-X.

- Estes, Donald H. (1978). "Asama Gunkan: The Reappraisal of a War Scare". Journal of San Diego History. 24 (3). Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- Evans, David & ISBN 0-87021-192-7.

- Forczyk, Robert (2009). Russian Battleship vs Japanese Battleship, Yellow Sea 1904–05. Botley, UK: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-330-8.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Fukui, Shizuo (1991). Japanese Naval Vessels at the End of World War II. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85367-125-8.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Hackett, Bob & Kingsepp, Sander (2012). "IJN Iwate: Tabular Record of Movement". SOKO-JUNYOKAN - Ex-Armored Cruisers. Combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- Hackett, Bob & Kingsepp, Sander (2014). "IJN Izumo: Tabular Record of Movement". SOKO-JUNYOKAN - Ex-Armored Cruisers. Combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- Harmsen, Peter (2013). Shanghai 1937: Stalingrad on the Yangtze. Havertown, Pennsylvania: Casemate. ISBN 978-1-61200-167-8.

- ISBN 978-1-906502-84-3.

- Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter & Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 0-87021-893-X.

- ISBN 978-0-81084-927-3.

- Lacroix, Eric & Wells, Linton (1997). Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-311-3.

- Milanovich, Kathrin (2014). "Armored Cruisers of the Imperial Japanese Navy". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2014. London: Conway. ISBN 978-1-84486-236-8.

- ISBN 1-59114-119-2.

- Saxon, Timothy D. (Winter 2000). "Anglo-Japanese Naval Cooperation, 1914–1918". Naval War College Review. LIII (1). Naval War College Press. Archived from the original on 13 December 2006.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Warner, Denis & Warner, Peggy (2002). The Tide at Sunrise: A History of the Russo-Japanese War, 1904–1905 (2nd ed.). London: Frank Cass. ISBN 0-7146-5256-3.