Prostate

| Prostate | |

|---|---|

pudendal plexus, vesical plexus, internal iliac vein | |

| Nerve | Inferior hypogastric plexus |

| Lymph | internal iliac lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | prostata |

| MeSH | D011467 |

| TA98 | A09.3.08.001 |

| TA2 | 3637 |

| FMA | 9600 |

| Anatomical terminology] | |

The prostate (

The prostate glands produce and contain fluid that forms part of semen, the substance emitted during ejaculation as part of the male sexual response. This prostatic fluid is slightly alkaline, milky or white in appearance. The alkalinity of semen helps neutralize the acidity of the vaginal tract, prolonging the lifespan of sperm. The prostatic fluid is expelled in the first part of ejaculate, together with most of the sperm, because of the action of smooth muscle tissue within the prostate. In comparison with the few spermatozoa expelled together with mainly seminal vesicular fluid, those in prostatic fluid have better motility, longer survival, and better protection of genetic material.

Disorders of the prostate include enlargement, inflammation, infection, and cancer. The word prostate comes from Ancient Greek προστάτης, prostátēs, meaning "one who stands before", "protector", "guardian", with the term originally used to describe the seminal vesicles.

Structure

The prostate is a

The internal structure of the prostate has been described using both lobes and zones.[6][3] Because of the variation in descriptions and definitions of lobes, the zone classification is used more predominantly.[3]

The prostate has been described as consisting of three or four zones.[3][5] Zones are more typically able to be seen on histology, or in medical imaging, such as ultrasound or MRI.[3][6] The zones are:

| Name | Fraction of adult gland[3] | Description |

| Peripheral zone (PZ) | 70% | The back of the gland that surrounds the distal urethra and lies beneath the capsule. About 70–80% of |

| Central zone (CZ) | 20% | This zone surrounds the ejaculatory ducts.[3] The central zone accounts for roughly 2.5% of prostate cancers; these cancers tend to be more aggressive and more likely to invade the seminal vesicles.[9] |

| Transition zone (TZ) | 5% | The transition zone surrounds the proximal urethra. |

| Anterior fibro-muscular zone (or stroma ) |

N/A | This area, not always considered a zone, fibrous tissue.[3]

|

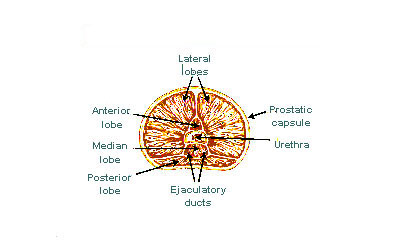

The "lobe" classification describes lobes that, while originally defined in the fetus, are also visible in gross anatomy, including dissection and when viewed endoscopically.[6][5] The five lobes are the anterior lobe or isthmus, the posterior lobe, the right and left lateral lobes, and the middle or median lobe.

-

Lobes of prostate

-

Zones of prostate

Inside of the prostate, adjacent and parallel to the prostatic urethra, there are two longitudinal muscle systems. On the front side (ventrally) runs the urethral dilator (musculus dilatator urethrae), on the backside (dorsally) runs the muscle switching the urethra into the ejaculatory state (musculus ejaculatorius).[10]

Blood and lymphatic vessels

The prostate receives blood through the

The veins of the prostate form a network – the

The lymphatic drainage of the prostate depends on the positioning of the area. Vessels surrounding the vas deferens, some of the vessels in the seminal vesicle, and a vessel from the posterior surface of the prostate drain into the external iliac lymph nodes.[5] Some of the seminal vesicle vessels, prostatic vessels, and vessels from the anterior prostate drain into internal iliac lymph nodes.[5] Vessels of the prostate itself also drain into the obturator and sacral lymph nodes.[5]

-

Imaging showing theinternal iliac arteries.

-

Image showing thevein

Microanatomy

The prostate consists of glandular and

The connective tissue of the prostate is made up of fibrous tissue and smooth muscle.[3] The fibrous tissue separates the gland into lobules.[3] It also sits between the glands and is composed of randomly orientated smooth-muscle bundles that are continuous with the bladder.[12]

Over time, thickened secretions called corpora amylacea accumulate in the gland.[3]

-

Microscopic glands of the prostate

-

Microanatomy of a prostatic gland, showing both luminal cells and surrounding basal cells. H&E stain.

Gene and protein expression

About 20,000

Development

In the developing

The prostatic part of the urethra develops from the middle, pelvic, part of the urogenital sinus, which is of

Condensation of

Function

In ejaculation

The prostate secretes fluid, which becomes part of the

In urination

The prostate's changes of shape, which facilitate the mechanical switch between urination and ejaculation, are mainly driven by the two longitudinal muscle systems running along the prostatic urethra. These are the urethral dilator (musculus dilatator urethrae) on the urethra's front side, which contracts during urination and thereby shortens and tilts the prostate in its vertical dimension thus widening the prostatic section of the urethral tube,[21][22] and the muscle switching the urethra into the ejaculatory state (musculus ejaculatorius) on its backside.[10]

In case of an operation, e.g. because of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), damaging or sparing of these two muscle systems varies considerably depending on the choice of operation type and details of the procedure of the chosen technique. The effects on postoperational urination and ejaculation vary correspondingly.[23]

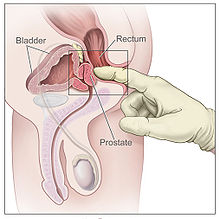

In stimulation

It is possible for some men to achieve orgasm solely through stimulation of the prostate gland, such as via prostate massage or anal intercourse.[24][25] This has led to the area of the rectal wall adjacent to the prostate to be popularly referred by the anatomically incorrect term, the "male G-spot".[26]

Clinical significance

Inflammation

Acute prostatitis and chronic bacterial prostatitis are treated with

Enlarged prostate

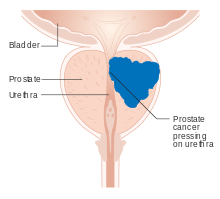

An enlarged prostate is called

BPH can be treated with medication, a minimally invasive procedure or, in extreme cases, surgery that removes the prostate. In general, treatment often begins with an alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonist medication such as tamsulosin, which reduces the tone of the smooth muscle found in the urethra that passes through the prostate, making it easier for urine to pass through.[27] For people with persistent symptoms, procedures may be considered. The surgery most often used in such cases is transurethral resection of the prostate,[27] in which an instrument is inserted through the urethra to remove prostate tissue that is pressing against the upper part of the urethra and restricting the flow of urine. Minimally invasive procedures include transurethral needle ablation of the prostate and transurethral microwave thermotherapy.[30] These outpatient procedures may be followed by the insertion of a temporary stent, to allow normal voluntary urination, without exacerbating irritative symptoms.[31]

Cancer

Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers affecting older men in the UK, US, Northern Europe and Australia, and a significant cause of death for elderly men worldwide.[32] Often, a person does not have symptoms; when they do occur, symptoms may include urinary frequency, urgency, hesitation and other symptoms associated with BPH. Uncommonly, such cancers may cause weight loss, retention of urine, or symptoms such as back pain due to metastatic lesions that have spread outside of the prostate.[27]

A

Prostate cancer that is only present in the prostate is often treated with either surgical

Sometimes, the decision may be made not to treat prostate cancer. If a cancer is small and localised, the decision may be made to monitor for cancer activity at intervals ("active surveillance") and defer treatment.[27] If a person, because of frailty or other medical conditions or reasons, has a life expectancy less than ten years, then the impacts of treatment may outweigh any perceived benefits.[27]

Surgery

Surgery to remove the prostate is called

The whole prostate can be removed. Complications that might develop because of surgery include

History

The prostate was first formally identified by

At the time, Du Laurens was describing what was considered to be a pair of organs (not the single two-lobed organ), and the

The fact that the prostate was one and not two organs was an idea popularised throughout the early 18th century, as was the English language term used to describe the organ, prostate,[38] attributed to William Cheselden.[39] A monograph, "Practical observations on the treatment of the diseases of the prostate gland" by Everard Home in 1811, was important in the history of the prostate by describing and naming anatomical parts of the prostate, including the median lobe.[38] The idea of the five lobes of the prostate was popularized following anatomical studies conducted by American urologist Oswald Lowsley in 1912.[6][39] John E. McNeal first proposed the idea of "zones" in 1968; McNeal found that the relatively homogeneous cut surface of an adult prostate in no way resembled "lobes" and thus led to the description of "zones".[40]

Prostate cancer was first described in a speech to the

The role of the

Other animals

The prostate is found only in mammals.[53] The prostate glands of male marsupials are proportionally larger than those of placental mammals.[54] The presence of a functional prostate in monotremes is controversial, and if monotremes do possess functional prostates, they may not make the same contribution to semen as in other mammals.[55]

The structure of the prostate varies, ranging from

The prostate gland originates with tissues in the urethral wall.[citation needed] This means the urethra, a compressible tube used for urination, runs through the middle of the prostate; enlargement of the prostate can constrict the urethra so that urinating becomes slow and painful.[68]

Prostatic secretions vary among species. They are generally composed of simple sugars and are often slightly alkaline.[69] In eutherian mammals, these secretions usually contain fructose. The prostatic secretions of marsupials usually contain n-Acetylglucosamine or glycogen instead of fructose.[70]

Skene's gland

Because the

See also

- Ejaculatory duct

- List of distinct cell types in the adult human body

- Prostate evolution in monotreme mammals

- Seminal vesicles

References

Citations

- ^ "PROSTATE | Pronunciation in English - Cambridge Dictionary".

- ISSN 0719-532X.

- ^ ISBN 9780702047473.

- PMID 90380.

- ^ )

- ^ doi:10.1002/tre.676.

- ^ a b "Basic Principles: Prostate Anatomy" Archived 2010-10-15 at the Wayback Machine. Urology Match. Www.urologymatch.com. Web. 14 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Prostate Cancer Information from the Foundation of the Prostate Gland." Prostate Cancer Treatment Guide. Web. 14 June 2010.

- S2CID 52417682.

- ^ ISBN 9783131395337, p. 298, PDF.

- ^ "Prostate Gland Development". ana.ed.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2003-04-30. Retrieved 2011-08-03.

- ^ "Prostate". webpath.med.utah.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-17.

- ^ "The human proteome in prostate – The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2017-09-26.

- S2CID 802377.

- PMID 26237329.

- PMID 24009853.

- ^ ISBN 9781496383907.

- ^ ISBN 9781496383907.

- ISBN 978-1-4160-3705-7.

- ^ OCLC 1076268769.

- S2CID 9423239.

- S2CID 31046054.

- S2CID 49556196. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2021-08-11. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

- ISBN 978-0618755714. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-8018-9396-4. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- PMID 29265651.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Davidson's 2018, pp. 437–9.

- ^ PMID 16952676.

- ^ "Physical Therapy Treatment for Prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- ^ Christensen, TL; Andriole, GL (February 2009). "Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Current Treatment Strategies". Consultant. 49 (2).

- PMID 18374395.

- PMID 31068988.

- PMID 23271765.

- ^ "What is Brachytherapy?". American Brachytherapy Society. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Surgery for Prostate Cancer". www.cancer.org. The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team. 1 August 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Surgery to remove your prostate gland | Prostate cancer | Cancer Research UK". www.cancerresearchuk.org. Cancer Research UK. 18 Jun 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- PMID 27591810.

- ^ S2CID 44922919.

- ^ S2CID 56476748.

- S2CID 33861863.

- .

- PMID 27591810.

- ^ PMID 21805756.

- PMID 11371867.

- Samuel David Gross (1851). A Practical Treatise On the Diseases and Injuries of the Urinary Bladder, the Prostate Gland, and the Urethra. Philadelphia: Blanchard and Lea.

"The idea of extirpating the entire gland is, indeed, too absurd to be seriously entertained... Excision of the middle lobe would be far less objectionable"

- ^ Young HH (1905). "Four cases of radical prostatectomy". Johns Hopkins Bull. 16.

- S2CID 30740301.

- ^ Huggins CB, Hodges CV (1941). "Studies on prostate cancer: 1. The effects of castration, of estrogen and androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate". Cancer Res. 1 (4): 293. Archived from the original on 2017-06-30.

- PMID 4941683.

- PMID 6461861.

- PMID 12044015.

- PMID 1104900.

- PMID 12645922.

- ISBN 978-0-521-33792-2.

- PMID 11999298.

- ISBN 9781133709510.

- ^ Nelsen, O. E. (1953) Comparative embryology of the vertebrates Blakiston, page 31.

- ISBN 978-1-118-71028-9.

- ISBN 978-1-4863-0753-1.

- ^ Australian Mammal Society. Australian Mammal Society. December 1978.

- ISBN 978-1-78064-316-8.

- ISBN 978-0-643-06257-3.

- ISBN 978-0-323-54602-7.

- ISBN 9781107000018.

- ISBN 9781437702828.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ISBN 978-0-08-091993-5.

- ^ Rommel, Sentiel A., D. Ann Pabst, and William A. McLellan. "Functional anatomy of the cetacean reproductive system, with comparisons to the domestic dog." Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny of Cetacea. Science Publishers (2016): 127–145.

- ISBN 9780199230846.

- ISBN 9780323263740.

- ISBN 978-1-139-45742-2.

- S2CID 5045626.

- ISBN 978-1135825096.

- ISBN 978-0323091312.

- OCLC 911037670.

- PMID 28400434.

General and cited sources

- Ralston, Stuart H.; Penman, Ian D.; Strachan, Mark W.; Hobson, Richard P., eds. (2018). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (23rd ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-7028-0.

- Attribution

- Portions of the text of this article originate from NIH Publication No. 02-4806, a public domain resource. "What I need to know about Prostate Problems". National Institutes of Health. 2002-06-01. No. 02-4806. Archived from the original on 2002-06-01. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

External links

Media related to Prostate at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Prostate at Wikimedia Commons