Cesar-Ranchería Basin

| Cesar-Ranchería Basin | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cuenca Cesar-Ranchería | ||

Field(s) Marracas | | |

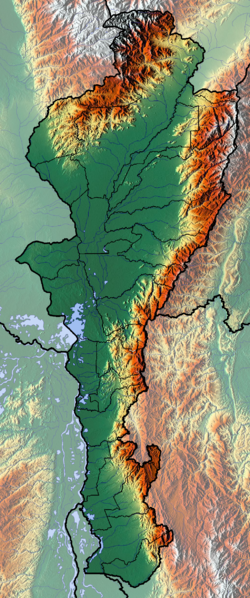

The Cesar-Ranchería Basin (Spanish: Cuenca Cesar-Ranchería) is a sedimentary basin in northeastern Colombia. It is located in the southern part of the department of La Guajira and northeastern portion of Cesar. The basin is bound by the Oca Fault in the northeast and the Bucaramanga-Santa Marta Fault in the west. The mountain ranges Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta and the Serranía del Perijá enclose the narrow triangular intermontane basin, that covers an area of 11,668 square kilometres (4,505 sq mi). The Cesar and Ranchería Rivers flow through the basin, bearing their names.

The basin is of importance for hosting the worldwide tenth biggest and largest

The Cesar-Ranchería Basin is relatively underexplored for hydrocarbons, compared to neighbouring hydrocarbon-rich provinces as the

Etymology

The name of the basin is taken from the Cesar and Ranchería Rivers.[1]

Description

The Cesar-Ranchería Basin is an

The sedimentary sequence inside the basin comprises Jurassic to Quaternary rocks, underlain by Paleozoic basement. An important unit is the Paleocene Cerrejón Formation, hosting major coal reserves, excavated in several open-pit mines of which Cerrejón in the northeast of the basin is the most striking. Cerrejón is the tenth biggest coal mine worldwide and the largest of Latin America.[5] The formation provides low-ash, low-sulphur bituminous coal with a total production in 2016 of almost 33 Megatons.[6] Other coal mines include La Francia, in the western Cesar portion of the basin. The total coal production of the Cesar-Ranchería Basin in 2016 was nearly 81 Megatons.[7]

The Cesar-Ranchería Basin is located at the northern edge of the

Petroleum exploration in the Cesar-Ranchería Basin commenced in 1916. The first exploitation of hydrocarbons was performed in 1921 and 1922 at Infantas in the Ranchería Basin and in 1938 the first well (El Paso-1) was drilled in the Cesar Basin.

Municipalities

| Municipality bold is capital |

Department | Altitude of urban centre |

Inhabitants 2015 |

Notes | Topography |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | La Guajira | 320 m (1,050 ft) |

26,606 |

| |

| Barrancas | La Guajira | 40 m (130 ft) |

34,619 |

||

| Hatonuevo | La Guajira | 50 m (160 ft) |

24,916 |

||

Distracción |

La Guajira | 65 m (213 ft) |

15,790 |

||

| Fonseca | La Guajira | 11.8 m (39 ft) |

33,254 |

||

| El Molino | La Guajira | 240 m (790 ft) |

8718 |

||

| San Juan del Cesar | La Guajira | 250 m (820 ft) |

37,327 |

||

| Villanueva | La Guajira | 250 m (820 ft) |

27,657 |

||

| Urumita | La Guajira | 255 m (837 ft) |

17,910 |

||

| La Jagua del Pilar | La Guajira | 223 m (732 ft) |

3213 |

||

| Valledupar | Cesar | 168 m (551 ft) |

473,232 |

| |

| Manaure Balcón del Cesar | Cesar | 775 m (2,543 ft) |

14,514 |

||

La Paz |

Cesar | 165 m (541 ft) |

22,815 |

||

Pueblo Bello |

Cesar | 1,200 m (3,900 ft) |

22,275 |

||

| San Diego | Cesar | 180 m (590 ft) |

22,815 |

||

| Agustín Codazzi | Cesar | 131 m (430 ft) |

50,829 |

||

| Bosconia | Cesar | 200 m (660 ft) |

37,248 |

||

| El Paso | Cesar | 36 m (118 ft) |

22,832 |

||

| Becerril | Cesar | 200 m (660 ft) |

13,453 |

||

La Jagua de Ibirico |

Cesar | 150 m (490 ft) |

22,283 |

||

| Chiriguaná | Cesar | 40 m (130 ft) |

19,650 |

||

| Curumaní | Cesar | 112 m (367 ft) |

24,367 |

||

| Chimichagua | Cesar | 49 m (161 ft) |

30,658 |

Tectonic history

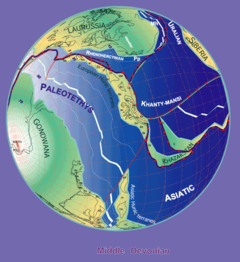

The tectonic history of the Cesar-Ranchería Basin has been subdivided into six phases. The basin started as a

Passive margin

The passive margin phase was characterised by the deposition of shallow marine sediments in three periods, divided by

Compressive margin I

Sediments from the Late Permian to Triassic periods are absent in the Cesar-Ranchería Basin, but evidenced in the surrounding orogens. Intense magmatism and metamorphism affected the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta and the

Rift basin

The break-up of Pangea in the Early Jurassic generated a sequence of rift basins in northern South America, surrounding the proto-Caribbean. The area of the present-day Serranía del Perijá was a continental rift, while basins to the west were marine in origin. Regional fault lineaments formed during this phase, that during the compression of the Andean orogenic stage were reactivated as thrust faults. The current compressional faults of the Cesar-Ranchería Basin are high-angle.[39]

The rift basin setting spanned the Jurassic period and was followed by post-rift sedimentation in the Early Cretaceous, evidenced by the Río Negro and Lagunitas Formations.[40]

Back-arc basin

During the Cretaceous, the basins of northern South America were connected in a back-arc basin setting. The first phase of the Andean orogeny uplifted the Western Ranges and was characterised by magmatism in the Sierra de San Lucas in the northern Central Ranges, dated to the Albian to Cenomanian epochs. Sedimentation on the northern South American platform was of siliciclastic and carbonate character, the latter more dominant in the northern areas. In the Cesar-Ranchería Basin, this led to the deposition of the main source rock formations of the basin, most notably La Luna.[40]

Compressive margin II

A second phase of compressive margin has been noted in the Cesar-Ranchería Basin by the strong differences between the sedimentary thicknesses of the Paleocene formations. During this stage in the basin development, the Cesar-Ranchería Basin was connected to the Middle Magdalena Valley to the west. The Paleocene Lisama Formation has a reduced thickness in the northern part of the Middle Magdalena Valley due to erosion, while the Paleocene section in the Cesar-Ranchería Basin is very thick. This has been explained by the tilt of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta and the formation of several thick-skinned thrust faults in the basin.[40] The initiation of this compressive phase has been dated to the Maastrichtian, when tectonic uplift and deformation was active in the Central Ranges, to the west of the basin.[41]

Intermontane foreland basin

While the Llanos Basin to the southeast experienced a foreland basin setting since the Paleogene, due to the first phases of uplift of the Eastern Ranges, the Cesar-Ranchería Basin was characterised by an intermontane basin setting with forming mountain ranges to the north and southeast; the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta and Serranía del Perijá respectively. Inside the basin, the main compressional movement is dated to this phase, where reverse faults were formed.[41]

Stratigraphy

The stratigraphy of the Cesar-Ranchería Basin has been described by various authors. The coal producing area was mapped in 1961.[42]

Paleontology

In the Cesar-Ranchería Basin several important fossils have been found, most notably in the Cerrejón Formation, together with the

Fossil content

Basin evolution

Paleozoic to Early Mesozoic

The Cesar-Ranchería Basin is underlain by

During the

| Paleogeography of Colombia | |

|

170 Ma |

|

150 Ma |

|

120 Ma |

|

105 Ma |

|

90 Ma |

|

65 Ma |

|

50 Ma |

|

35 Ma |

|

20 Ma |

|

Present |

Early to Late Mesozoic

The sedimentary sequence drilled in the basin starts with the

The Lower Cretaceous series is followed by the deposition of the regional main source rock of northern Colombia and northwestern Venezuela,

Paleogene to recent

At the end of the Cretaceous, the tectonic regime changed to a compressive phase, due to the movement of the Caribbean Plate.

During the Eocene and Early Oligocene, the western part of the basin was exposed and modest deposition concentrated in the Ranchería Sub-basin. The previously humid ecosystem changed to an arid plain environment.[108] In contrast, the Neogene conglomerates of the Cuesta Formation show a larger thickness in the southwestern part of the basin, close to the connected Middle Magdalena Valley.[109] During this period, especially in the Late Miocene to Pliocene, the Oca and Bucaramanga-Santa Marta Faults were tectonically active,[110] which is still observed in the present day.[111] Ongoing uplift and reverse faulting created the intermontane fluvial-dominated basin architecture of today.[109]

Economic geology

Petroleum geology

Despite various detailed studies and the similarities with neighbouring hydrocarbon rich provinces as the

Mining

Coal mining in the Cesar-Ranchería Basin is concentrated in the northeast, with

A study published in 2015 on the La Quinta Formation, shows the presence of 1.45% of copper, present mainly in malachite mineralisations in the volcanoclastic beds of the formation.[118]

See also

- Geology of Colombia

- Geology of the Ocetá Páramo

- Geology of the Eastern Hills

- Maracaibo Basin

- Middle Magdalena Valley

- Bogotá Formation, Honda Group

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ 2017 population data

References

- ^ Arias & Morales, 1994, p.11

- ^ Barrero et al., 2007, p.35

- ^ Ayala, 2009, p.13

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p ANH, 2010

- ^ The 10 biggest coal mines in the world

- ^ Cerrejón

- ^ a b (in Spanish) Producción de carbón en Colombia - UPME

- ^ Ayala, 2009, p.11

- ^ a b Olshansky et al., 2007, p.13

- ^ Mojica et al., 2009, p.17

- ^ Mojica et al., 2009, p.18

- ^ Vargas Jiménez, 2012, p.35

- ^ a b c Garzón, 2014, p.14

- ^ Garzón, 2014, p.10

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Albania, La Guajira

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Barrancas, La Guajira

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Hatonuevo

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Distracción

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Fonseca, La Guajira

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website El Molino, La Guajira

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website San Juan del Cesar

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Villanueva, La Guajira

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Urumita

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website La Jagua del Pilar

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Valledupar

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Manaure Balcón del Cesar

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website La Paz, Cesar

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Pueblo Bello, Cesar

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website San Diego, Cesar

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Agustín Codazzi, Cesar

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Bosconia

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website El Paso, Cesar

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Becerril

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website La Jagua de Ibirico

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Chiriguaná

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Curumaní

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Chimichagua

- ^ Ayala, 2009, pp.15-17

- ^ a b c Ayala, 2009, p.15

- ^ a b c Ayala, 2009, p.16

- ^ a b c Ayala, 2009, p.17

- ^ Plancha 41, 1961

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m ANH, 2007, p.65

- ^ Ayala, 2009. p.34

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Plancha 47, 2001

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Plancha 48, 2008

- ^ a b García González et al., 2007, p.83

- ^ a b c Ayala, 2009. p.30

- ^ García González et al., 2007, p.79

- ^ García González et al., 2007, p.78

- ^ a b Ayala, 2009, p.29

- ^ a b c Ayala, 2009, p.27

- ^ a b c Ayala, 2009, p.26

- ^ a b c d e Plancha 34, 2007

- ^ a b c Ayala, 2009, p.24

- ^ a b c Ayala, 2009. p.23

- ^ a b c Ayala, 2009, p.22

- ^ García González et al., 2007, p.67

- ^ a b Ayala, 2009, p.20

- ^ a b Ayala, 2009. p.19

- ^ Head et al., 2009, p.717

- ^ Titanoboa cerrejonensis at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Head et al., 2009

- ^ Acherontisuchus guajiraensis at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Hastings et al., 2011, p.1095

- ^ Anthracosuchus balrogus at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Hastings et al., 2014

- ^ Cerrejonisuchus improcerus at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Hastings et al., 2010

- ^ Carbonemys cofrinii at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Cadena et al., 2012a

- ^ Cerrejonemys wayuunaiki at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Cadena et al., 2010

- ^ Puentemys mushaisaensis at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Cadena et al., 2012b

- ^ Herrera et al., 2011

- ^ Herrera et al., 2008

- ^ Herrera et al., 2014, p.199

- ^ Herrera et al., 2014, p.204

- ^ Wing et al., 2009

- ^ Cerrejón 0315 at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Cerrejón 0318 at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Cerrejón 0319 at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Cerrejón 0322 at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Cerrejón 0323 at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Cerrejón 0324 at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Cerrejón 0706 at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Cerrejón 0707 at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Cerrejón 0708 at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Cerrejón 0710 at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Cerrejón FH0705-12 at Fossilworks.org

- ^ a b c García González et al., 2007, p.303

- ^ García González et al., 2007, p.77

- ^ a b c García González et al., 2007, p.307

- ^ a b García González et al., 2007, p.75

- ^ García González et al., 2007, p.68

- ^ Ayala, 2009, p.18

- ^ Paleomap Scotese 356 Ma

- ^ Ayala, 2009, p.21

- ^ Ayala, 2009, p.25

- ^ Naafs et al., 2016, p.135

- ^ Ayala, 2009, p.28

- ^ Ayala, 2009, p.64

- ^ Ayala, 2009, p.65

- ^ Wing et al., 2009, p.18629

- ^ Bayona et al., 2007, p.41

- ^ Ayala, 2009, p.73

- ^ Ayala, 2009, p.74

- ^ a b Ayala, 2009, p.66

- ^ Hernández Pardo et al., 2009, p.28

- ^ Cuéllar et al., 2012, p.77

- ^ Olshansky et al., 2007, p.16

- ^ García González et al., 2007, p.16

- ^ Olshansky et al., 2007, p.83

- ^ Hernández Pardo et al., 2009, p.54

- ^ Geoestudios & ANH, 2006, p.94

- ^ (in Spanish) Producción de oro - UPME

- ^ Cardeño Villegas et al., 2015, p.123

Bibliography

General

- Barrero, Dario; Andrés Pardo; Carlos A. Vargas, and Juan F. Martínez. 2007. Colombian Sedimentary Basins: Nomenclature, Boundaries and Petroleum Geology, a New Proposal, 1–92. ANH.

- García González, Mario; Ricardo Mier Umaña; Luis Enrique Cruz Guevara, and Mauricio Vásquez. 2009. Informe Ejecutivo - evaluación del potencial hidrocarburífero de las cuencas colombianas, 1–219. Universidad Industrial de Santander.

- Garzón, José William. 2014. Recursos de CBM en Colombia - estimación del potencial, 1–31. ANH. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- Naafs, B.D.A.; J.M. Castro; G.A. De Gea; M.L. Quijano; D.N. Schmidt, and R.D. Pancost. 2016. Gradual and sustained carbon dioxide release during Aptian Oceanic Anoxic Event 1a. Nature Geoscience 9(2). 135–139. Accessed 2017-06-14.

Cesar-Ranchería Basin

Cesar-Ranchería general

- Arias, Alfonso, and Carlos J. Morales. 1994. Evaluación del agua subterránea en el Departamento del Cesar, 1–107. INGEOMINAS.

- Ayala Calvo, Rosa Carolina. 2009. Análisis tectonoestratigráfico y de procedencia en la Subcuenca de Cesar: Relación con los sistemas petroleros (MSc.), 1–255. Universidad Simón Bolívar. Accessed 2017-06-14. Archived 2021-12-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Bayona, Germán; Felipe Lamus Ochoa; Agustín Cardona; Carlos Jaramillo; Camilo Montes, and Nadejda Tchegliakova. 2007. Procesos orogénicos del Paleoceno para la cuenca de Ranchería (Guajira, Colombia) y áreas adyacentes definidos por análisis de procedencia. Geología Colombiana 32. 21–46. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- Cardeño Villegas, Karol; Elias Ernesto Rojas Martínez; Dino Carmelo Manco Jaraba, and Rony Rafael Cárdenas López. 2015. Identificación de las Mineralizaciones de Cobre Aflorantes en el Corregimiento de San José de Oriente, La Paz, Cesar. Ingeniare 18(18). 115–125. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- Cardona, A.; V.A. Valencia; G. Bayona; J. Duque; M. Ducea; G. Gehrels; C. Jaramillo; C. Montes, and G. Ojeda & J. Ruiz. 2011. Early-subduction-related orogeny in the northern Andes: Turonian to Eocene magmatic and provenance record in the Santa Marta Massif and Rancheria Basin, northern Colombia. Terra Nova 23. 26–34. Accessed 2018-05-12.

- Cuéllar Cárdenas, Mario Andrés; Julián Andrés López Isaza; Jairo Alonso Osorio Naranjo, and Edgar Joaquín Carrillo Lombana. 2012. Análisis estructural del segmento Bucaramanga del Sistema de Fallas de Bucaramanga (sfb) entre los municipios de Pailitas y Curumaní, Cesar - Colombia. Boletín de Geología 34. 73–101. Accessed 2017-06-09.

- García González, Mario; Ricardo Mier Umaña; Andrea F. Arias R.; Yeny M. Cortes P.; Mario A. Moreno C.; Oscar M. Salazar C., and Miguel F. Jiménez J. 2007. Prospectividad de la cuenca Cesar-Ranchería, 1–336. ANH.

- Hernández Pardo, Orlando; José María Jaramillo; Mauricio Parra; Armando Salazar; Raymond Donelick, and Astrid Blandón. 2009. Reconstrucción de la historia termal en el piedemonte occidental de la Serranía del Perijá entre Codazzi y La Jagua de Ibirico - Cuenca de Cesar-Ranchería, 1–85. Universidad Nacional de Colombia & ANH. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- Ojeda Marulanda, Carolina, and Carlos Alberto Sánchez Quiñónez. 2013. Petrografía, petrología y análisis de procedencia de unidades paleógenas en las cuencas Cesar - Ranchería y Catatumbo. Boletín de Geología 35. 67–80. Accessed 2017-06-14.

Cerrejón Formation

- Cadena, Edwin A.; Daniel T. Ksepka; Carlos A. Jaramillo, and Jonathan I. Bloch. 2012a. New pelomedusoid turtles from the late Palaeocene Cerrejón Formation of Colombia and their implications for phylogeny and body size evolution. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 10(2). 313–331. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- Cadena, Edwin A.; Jonathan I. Bloch, and Carlos A. Jaramillo. 2012b. New bothremydid turtle (Testudines, Pleurodira) from the Paleocene of northeastern Colombia. Journal of Paleontology 86(4). 688–698. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- Cadena, Edwin A.; Jonathan I. Bloch, and Carlos A. Jaramillo. 2010. New Podocnemidid Turtle (Testudines: Pleurodira) from the Middle-Upper Paleocene of South America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30(2). 367–382. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- Hastings, Alexander K.; Jonathan I. Bloch, and Carlos A. Jaramillo. 2014. A new blunt-snouted dyrosaurid, Anthracosuchus balrogus gen. et sp. nov. (Crocodylomorpha, Mesoeucrocodylia), from the Palaeocene of Colombia. Historical Biology 27(8). 998–1020. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- Hastings, Alexander K.; Jonathan I. Bloch, and Carlos A. Jaramillo. 2011. A new longirostrine Dyrosaurid (Crocodylomorpha, Mesoeucrocodylia) from the Paleocene of north-eastern Colombia: Biogeographocal and behavioural implications for New-World Dyrosayridae. Palaeontology 54. 1095–1116. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- Head, J.J.; J.I. Bloch; A.K. Hastings; J.R. Bourque; E.A. Cadena; F.A. Herrera; P.D. Polly, and C.A. Jaramillo. 2009. Giant boid snake from the paleocene neotropics reveals hotter past equatorial temperatures. Nature 457(7230). 715–718. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- Herrera, Fabiany A.; Carlos A. Jaramillo; David L. Dilcher; Scott L. Wing, and Carolina Gómez N. 2008. Fossil Araceae from a Paleocene neotropical rainforest in Colombia. American Journal of Botany 95(12). 1569–1583. Accessed 2017-06-14.[permanent dead link]

- Wing, Scott L.; Fabiany Herrera; Carlos A. Jaramillo; Carolina Gómez Navarro; Peter Wilf, and Conrad C. Labandeira. 2009. Late Paleocene fossils from the Cerrejón Formation, Columbia ((sic)), are the earliest record of Neotropical rainforest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106(44). 18627–18632. .

Petroleum geology

- Garzón, José William. 2014. Recursos de CBM en Colombia - estimación del potencial, 1–31. ANH. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- Geoestudios &, ANH. 2006. Cartografía geológica cuenca Cesar-Ranchería, 1–95. ANH.

- Mojica, Jairo; Oscar J. Arévalo, and Hardany Castillo. 2009. Cuencas Catatumbo, Cesar – Ranchería, Cordillera Oriental, Llanos Orientales, Valle Medio y Superior del Magdalena, 1–65. ANH. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- Olshansky, A.S.; E.L. Kuzmin, and V.V. Maslianitzkiy. 2007. Programa sísmico Cesar-Ranchería 2D - reporte final de procesamiento e interpretación, 1–84. ANH. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- Vargas Jiménez, Carlos A. 2012. Evaluating total Yet-to-Find hydrocarbon volume in Colombia. Earth Sciences Research Journal 16. 1–290. .

- N., N. 2010. Cuenca Cesar-Ranchería - Open Round Colombia 2010, 1. ANH. Accessed 2017-06-14.

Maps

- Colmenares, Fabio; Milena Mesa; Jairo Roncancio; Edgar Arciniegas; Pablo Pedraza; Agustín Cardona; César Silva; Jhoamna Romero, and Sonia Alvarado and Oscar Romero, Felipe Vargas, Carlos Santamaría. 2007. Plancha 34 - Agustín Codazzi - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- N., N. 1961. Plancha 41 - Mapa geológico de la cuenca carbonífera Cesar-Ranchería - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- Hernández, Marina; Jairo Clavijo, and Javier González. 2001. Plancha 47 - Chiriguaná - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- Hernández, Marina, and Jairo Clavijo. 2008. Plancha 48 - La Jagua de Ibirico - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-14.

Further reading

- Bally, A.W., and S. Snelson. 1980. Realms of subsidence. Canadian Society for Petroleum Geology Memoir 6. 9–94. .

- Kingston, D.R.; C.P. Dishroon, and P.A. Williams. 1983. Global Basin Classification System. AAPG Bulletin 67. 2175–2193. Accessed 2017-06-23.

- Klemme, H.D. 1980. Petroleum Basins - Classifications and Characteristics. Journal of Petroleum Geology 3(2). 187–207. Accessed 2017-06-23.