Church of the Holy Apostles (Ani)

40°30′32″N 43°34′14″E / 40.508798°N 43.570685°E

The Church of the Holy Apostles, also Surp Arak’elots (Armenian: Սուրբ Առաքելոց եկեղեցի, Surb Arakelots yekeghets’i, "Holy Apostles Church"),[3] is an important ecclesiastical monument of the ruined city of Ani, modern Turkey, on the border with Armenia.[4]

The Church is composed in two parts: the church itself, now largely ruined, and the colonnated gavit in front of it, remaining in large part.[4]

The remains of the gavit are clearly derived from Seljuk architectural designs.[5]

The old Armenian Church (c. 1031)

The Church itself was built before 1031, date of a now lost inscription over the south entrance to the church, which was left by

The dedicatory inscription in Armenian on top of the entrance to the church reads:

In 480 (ie 1031), by the Grace of God, I, Abughamir, son of Vahram, Prince of Princes, have given the camp of Carnut to the Saint Apostoles, for the health and prolongation of the life of my brother Grigor.

— Dedicatory inscription.[6]

-

The church before the construction of the gavit in front

-

Detailed plan of the church

-

Entrance gate of the old church with a lintel decorated with acanthus leaves, and a dedicatory inscription. View from outside the church, from inside the gavit

-

Gate of the old church, viewed from inside the church

-

Remains of the Church (interior to north apse)

The gavit or narthex (1031-1215)

Having a colonnaded

The overall design of this wall is very similar to the design of the gate of the Mama Hatun mausoleum at Tercan, dated to c. 1200, and belonging to the Seljuk Saltukids dynasty.[4] The vault design is also similar to that of the Bagnayr Monastery, which is dated by an inscription to 1201, supporting a date of around 1200 for the zhamatun of the Church of the Holy Apostoles.[8]

In 1064, the Seljuk sultan

The style of the vault is considered as similar to that of the

-

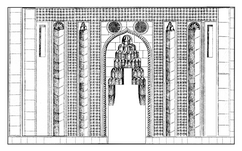

Eastern entrance gate with muqarnas

-

Eastern side of the Seljuk gavit, with entrance

-

Plan of the church and the gavit. The church followed a traditionnal Byzantine design, while the gavit in front of it was in Seljuk caravanserai style.

-

Design of the roof of the gavit. Muqarnas door to the right, roof with three ceiling boxes and an ex-centered vault.

-

Entrance withMuqarna(viewed from the inside)

-

Vault design with 360°Muqarna

Adoption of muqarnas styles in Armenian art

The muqarnas motif was clearly inspired by Islamic sources, but it was used differently, and the Armenian muqarnas vault with oculus was not found in the Muslim world until it was copied about a century later, as in the vault of the Yakutiye Madrasa in nearby Erzurum (1310).[15]

Il-Khanate imperial decrees

Ani was under Armenian

From around 1260, with the Mongol

An inscription in the name of the Il-Khan is dated 1269, and reports the cancellation of taxes:

718 (ie 1269). (In the name) of the Il-khan.

By the grace of God, we, customs officers, for the longevity of our masters, Sahip-Divan, Sahmad and Qarimadin, have removed from Ani the tax for priests that this city did not pay not originally; we confirm (this exemption again). No one has the right to demand tax, whatever nationality or family he may be. The one who [said] otherwise or who bothers to [request] the tax, is cursed by the 318 Fathers; those who observe] (this) are blessed by God. I[srael the writer].— Inscription of 1269.[18]

Another one in 1276:

In 725 (ie 1276). (In the name) of the

Il-khan.

For the longevity of the Padishah and the Saïp-Divan,[19] we, customs officers of Ani: Hindutchakh, (who) is the son of the lord judge, Oussup from Za[ta], Gorg from Nouât, and the mercer Baulé, and the gdrik of the oven, we gave this writing to the controllers (?) of Ani, having noticed that they were encouraged by unfair customs officials, and we have removed (them). They perceived on each beast of burden half of its charge (?); we, the aforementioned customs officers, have abolished (this) for the longevity of the Padishah.

Also in the name of the Il-Khan, an inscription by Bishop Mkhithar, dated to circa 1276, under the authority of dom Sargis and Malik Phakhradin, prohibiting commerce on Sundays in the street, following an earthquake that year (located in one of the alcoves of the gavit).[20]

In the name of the Il-khan. By the grace of God, under the government of this city, under the superiority of Dom Sarguis, and under the authority of the melik Phakhradin, I Bishop Mkhithar, originally from Teglier, because of the earthquake that took place these days, we have eliminated the Sunday trade in the street. [He who] opposes this writing, great or small, is responsible for sins of this city.[20]

Other inscriptions

Other important incriptions in the Church of the Holy Apostles include:

- A 1217 inscription by Archibishop dom Grigor, son of Apughamr, announcing the cancellation of taxes for Shirak Province and the churches of Ani.[21]

- A 1253-1276 inscription by Agbugha I, son of muqarna decoration).[22]

- A 1303 inscription by Agbugha II, son of Ivane II, lamenting about the high level of taxes, and announcing the cancellation of several of them.[23]

- A 1320 inscription by Princess Kuandze, wife of Shahnshah II Zakarian (inside the gavit, on the inside of the arcade next to the gate of the church).[24]

- A 1348 inscription by a certain Chapadin, son of Hovhannes, donating gift for the monks of the church (inside wall of the gavit).[25]

See also

External links

- "Ani, église des Saints-Apôtres (Many high quality photographs)". Vanker.org : Monuments et sites au fil de l’Akhourian et autour du lac de Van (in French).

References

- .

The only parallels to them come from the Christian monuments of the Caucasus, such as the zhamatun of the church of the Holy Apostles in Ani, and the Akhlati-built Sitte Melik in Divrigi.

- ^ Eastmond, Antony (PhD in the art of medieval Georgia in the Caucasus, Oxford University). "Church of the Holy Apostles". Crossing Frontiers. The Courtauld Institute of Art, London.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Akture, Zeynep (2019). Unesco World Herıtage ın Turkey 2019. Unesco. pp. 466–477.

- ^ The Courtauld Institute of Artin London.

- ^ a b Eastmond, Antony (1 January 2014). "Inscriptions and Authority in Ani". Der Doppeladler. Byznanz und die Seldschuken in Anatolien vom späten 11. Bis zum 13. Jahrhundert, eds. Neslihan Austay-Effenberger, Falko Daim: 81.

This was an early 11th-century church that was expanded in the early 13th century by the addition of a gavit on its southern side. In form this building was clearly indebted to Seljuq architectural designs, both for the overall structure of its porch (fig. 10), and for the muqarnas construction of its central dome. The architectural similarities highlight the importance of texts as a means of articulating identity in Ani when so many other facets of the contemporary environment were almost indistinguishable from that of the Seljuq world around them.

- ISBN 978-1-4632-2085-3.

[En 180, par la grâce de Dieu, moi, Apoughamr, fils de Vahram, prince des princes, j'ai donné] le champ [de Ca]rnout aux [Saints-Apôtres, pour la santé et la prolongation [de la vie de mon frère Grigor.]

- ^ Marouti, Andreh (2018). Preservation of the architectural heritage of Armenia: a history of its evolution from the perspective of the early 19th century european travelers to the scientific preservation of the soviet period by Andreh Marouti · 3035215335 · OA.mg. Faculty of Preservation of Architectural Heritage Department of DASTU Politecnico di Milano. p. 136, Fig.18.

- .

Many of these overlaps come together in one building, the zhamatun that was added to the early eleventh-century church of the Holy Apostles in Ani some time shortly before 1217 (the earliest inscription on the building). Note 25: A date of around 1200 is supported by the similarity of the vaulting of the zhamatun of the monastery at Bagnayr, where the earliest inscription dates to 1201.

- ^ a b c d e f "Archaeological Site of Ani (Turkey) No 1518". Unesco. pp. 176–177.

- .

- .

This date is based on the similarity between its stone vaults and those of the zhamatun of the church of the Holy Apostles, which has a terminus ante quem of 1217, determined by the earliest surviving inscription there: Orbeli, Corpus Inscriptionum Armenicarum, no. 56; Basmadjian, Inscriptions armeniennes d'Ani, no. 49.

- ISBN 978-0-19-026901-2.

- ^ JSTOR 1523305.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4744-1130-1.

- Nur al-Din Zangi's 1174 hospital in Damascus, but conceived very differently: the monastic muqarnas are structurally pendentives, whereas the Damascus dome is a succession of stucco squinches. A generation later the Armenian use of muqarnas was re-imported into the Muslim world, and buildings such as the Yakutiye Madrasa in Erzurum (1310) copied the idea of a muqarnas vault around an oculus.

- ^ a b c d Eastmond, Antony (1 January 2014). "Inscriptions and Authority in Ani". Der Doppeladler. Byznanz und die Seldschuken in Anatolien vom späten 11. Bis zum 13. Jahrhundert, eds. Neslihan Austay-Effenberger, Falko Daim: 81.

By the 1260s, at which time Ani was under Ilkhanid rule, the gavit seems to have acted as a central deposit for legal affairs, especially those concerning taxes and import duties. The interior and exterior of the building are replete with inscriptions recording changes to levies – usually the alleviation of taxes, but occasionally impositions (such as the ban on Sunday street trading after the earthquake. These texts show a marked difference from the earlier Shaddadid inscriptions in the city about trade. Whereas those inscriptions were in Persian, these are all in Armenian, despite their ultimate authority coming from Iran. Indeed six of the inscriptions begin their texts with the words "[In the name of] the Ilkhan". They even adopt Mongolian terms, notably the word yarligh (imperial decree) which appears in the inscription of 1270.

- ^ a b c

Basmadjian, K.J. (1922–23). Graffin, René (ed.). "LES INSCRIPTIONS ARMÉNIENNES D'ANI DE BAGNA1R ET DE MARMACHÈN". Revue de l'Orient Chrétien (1896-1946): 341–42, inscription 72. ISBN 978-1-4632-2086-0.

- ISBN 978-1-4632-2086-0.

- JSTOR 4030920.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4632-2086-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4632-2086-0.

- ISBN 978-1-4632-2086-0.

- ISBN 978-1-4632-2086-0.

- ISBN 978-1-4632-2086-0.

- ISBN 978-1-4632-2086-0.