Eastern Approaches

OCLC 6486798 | | |

Eastern Approaches (1949) is a memoir of the early career of Fitzroy Maclean. It is divided into three parts: his life as a junior diplomat in Moscow and his travels in the Soviet Union, especially the forbidden zones of Central Asia; his exploits in the British Army and SAS in the North Africa theatre of war; and his time with Josip Broz Tito and the Partisans in Yugoslavia.

Maclean was considered to be one of the inspirations for James Bond,[1] and this book contains many of the elements: remote travel, the sybaritic delights of diplomatic life, violence and adventure. The American edition was titled Escape To Adventure, and was published a year later. All place names in this article use the spelling in the book.

Golden Road: the Soviet Union

Fresh out of

The Caucasus

In the spring of 1937, he took a trial trip, heading south from Moscow to

To Samarkand

His second trip, in the autumn of the same year, took him east along the

Maclean spent the winter working in Moscow and amusing himself at the

To Chinese Turkestan

When the weather became more conducive to travel, Maclean began his third and longest trip, aiming for

To Bokhara and Kabul

His fourth and final Soviet trip was once more to Central Asia, spurred by the desire to reach Bokhara (

Orient Sand: the Western Desert Campaign

The middle section of the book details Maclean's first set of experiences in

Joining up

The first challenge Maclean faced was getting into military service at all. His Foreign Office job was a

Benghazi and the desert retreat

After basic training, Maclean was sent to

Once he had recovered, Stirling involved him in preparations for a larger SAS attack on Benghazi. They attended a dinner with Churchill, the

The arrest of the Persian general

In September 1942 Maclean was ordered to

By the end of the year, the war had developed in such a way that the new SAS detachment would not be needed in Persia. General Wilson was being transferred to

Balkan War: With Tito in Yugoslavia

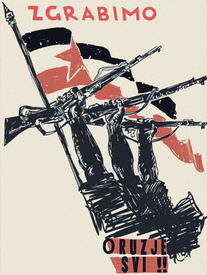

The final and longest section of the book covers Maclean's time in and around Yugoslavia, from the late summer of 1943 to the formation of the united government in March 1945.

The list of characters

In the late summer of 1943, Maclean parachuted into

Some of the characters close to Tito whom Maclean met in his first months in Bosnia were

Other Yugoslavs of note whom he met later included

Officers and soldiers under Maclean's command included Peter Moore of the Royal Engineers; Mike Parker, Deputy Assistant Quartermaster general; Gordon Alston; John Henniker-Major, a career diplomat; Donald Knight, and Robin Whetherly.

Maclean arranged for an Allied officer, under his command, to be attached to each of the main Partisan bases, bringing with him a radio transmitting set. Maclean was not in fact the first Allied officer in Yugoslavia, but the few who had been dropped before him had not been able to get much of their information out. Maclean made contact with Bill Deakin, an Oxford history don who had served as a research assistant to Churchill; Anthony Hunter, a Scots Fusilier, and Major William Jones, an enthusiastic but unorthodox one-eyed Canadian.

First journey across Bosnia and Dalmatia

Maclean saw his task as arranging supplies and air support for the Partisan fight, to tie up the Axis forces for as long as possible. The Royal Air Force was reluctant to risk landing on what they saw as an amateur airstrip at Glamoj (Glamoč), although Slim Farish was in fact an airfield designer, and night air drops were sporadic. The Royal Navy was approached, and they offered to bring supplies to an outlying island off the Dalmatian coast. Maclean and a couple of companions set off on foot for Korčula, being passed from guerilla group to guerilla group. They passed through battle-scarred villages and towns that had changed hands many times, some so recently that corpses still lay on the ground: Bugojno and Livno and Aržano. Once, they were billeted with a landlady whose sympathies clearly did not lie with the Partisans; she would not sell them food, but there was no question of simply commandeering it. Eventually, after an all-night march across noisy stony ground, dodging German patrols as they crossed a major road, the little group reached Zadvarje, where they were greeted with astonishment as creatures from another world "as indeed in a sense we were". After a few hours' sleep, they continued over the final range of hills to the coast, and down to Baška Voda, where a fishing boat took them circuitously to Korčula. There, all seemed in order for a Navy supply drop, but the wireless set developed problems. Maclean was on the point of returning to Jajce when the motor launch arrived, with a crew that included Sandy Glen (also, like Maclean, thought to be one of the inspirations for James Bond) and David Satow. By this point the enemy were closing in to take the remaining access points to the coast, which would throttle the Partisan supply route before it had even begun. He sent top priority requests, asking for air and sea support from Allied bases in Italy, and these took effect. Maclean decided he needed to discuss matters with Tito and then with Allied superiors in Cairo to argue for more resources to push the project forward, and accordingly made his way back to Partisan HQ in Jajce. He returned to the islands, first on Hvar and then on Vis, to wait for the response to his strongly worded signals. On Vis he discovered an overgrown British war cemetery dating from a naval victory over the French in 1811.

Gaining support

In Cairo Maclean dined with Alexander Cadogan, his FO superior, and the next day reported to

Churchill received him in trademark fashion: in bed, wearing an embroidered dressing gown, smoking a cigar. He, Joseph Stalin, and Franklin D. Roosevelt had discussed the matter of Yugoslavia at a recent conference in Teheran, and had decided to give all possible support to the Partisans. This was the turning point. The Chetniks were given a task (a bridge to blow up) and a deadline, to show whether they could still be effective allies; they failed this test and supplies were re-directed from them to the Partisans. The British government was left with the tricky political and moral problem of King Peter and his royalist government in exile. But the main issues were air supplies and air support, and to help co-ordinate this, Maclean's mission was expanded. Some of the new officers included Andrew Maxwell of the Scots Guards, John Clarke of the 2nd Scots Guards, Geoffrey Kup, a gunnery expert, Hilary King, a signals officer, Johnny Tregida, and, for a time, Randolph Churchill. Some of these were SAS or otherwise known from the Western Desert Campaign the previous year.

Marshal of Yugoslavia

Maclean returned to the islands and settled on

The Partisan headquarters moved to the village of Drvar, where Tito took up residence in a cave with a waterfall. Maclean spent months there with him, "talking, eating, and above all, arguing". He and Tito agreed a system of allocating the air drop supplies around the country, although there was some friction from officers wanting a bigger share. Air drops became much more frequent, as did air support for Partisan operations. At this point all support for the Cetniks was withdrawn, a fact Churchill announced in the House of Commons. Maclean decided to go to Serbia to see for himself what this stronghold of Cetniks held for the Partisans. In early April, before this could be arranged, he was ordered to London for further discussions. (A stop-over in Algiers meant a specially arranged radio phone call with Churchill. Maclean, who hated telephone conversations, managed to wring amusement from the mix-ups of codes and scrambling. Churchill's son was referred to as Pippin.)

They arrived in England to find "the whole of the southern counties [were] one immense armed camp". Despite the tension over the anticipated

Negotiating the future of Yugoslavia

Vis had been transformed in the intervening months, becoming a substantial base for aircraft, commandos, and navy boats "engaged in piratical activities against enemy shipping up and down the whole length of the Jugoslav coastline from

The negotiations that followed were called the Naples Conference, with Tito, Velebit and Olga on one side of the table and Churchill and Maclean on the other. Churchill was happy to give this matter his personal attention, and, Maclean says, he did it very well. One day the two leaders were taking a rest, having handed things over to a committee of experts, when a matter arose required Churchill's immediate attention. Maclean was sent to find him; he was believed to be bathing in the Bay of Naples. When they got to the shore, they saw the huge flotilla of troopships setting off for the south of France (Operation Dragoon), and a small bright blue admiral's barge dodging around them. Maclean was assigned a little torpedo boat, complete with a cautious captain and an attractive stenographer. It zoomed after the barge, eventually catching up with the prime minister, who found Maclean and his crew's arrival a source of much hilarity.

Immediately after the Naples Conference, Tito continued the diplomatic discussions on Vis, this time with

Planning for action

But by this point Maclean had had enough of high politics and garrison life. He wanted to be back in the action, and it looked as if the Germans were planning to withdraw from Yugoslavia. Accordingly, he came up with a plan known as Operation Ratweek, in which the Partisans and Allies were to harass the Axis troops in close co-ordination for seven days, destroying their communication lines. Bill Elliot, in command of the Balkan Air Force, supported the plan, as did the Navy and General Wilson. Tito committed himself too, although, as Maclean points out, it would have been understandable had he wished to let the Germans leave as soon as possible. Maclean got permission from Churchill to go to Serbia, previously a stronghold of the Chetniks, to supervise Ratweek from there.

He landed at

End stages

From Bari, he calculated that Tito would want to be directing the

A few days later, Tito arrived, and Maclean had to convey Churchill's displeasure at his sudden and unexplained departure. Tito had been to Moscow at Stalin's invitation to arrange matters with the Soviet High Command. Maclean helped to hammer out a draft agreement, and went to London with it, while Tito's envoys took it to Moscow. "It was a difficult and thankless task. King Peter, quite naturally, was not easy to reassure, and Tito, sitting in Belgrade with all the cards in his hand, was not easy to satisfy". The bargaining went on for months, and meanwhile Maclean's staff wanted to get away, to assist guerrilla wars elsewhere When the Big Three (Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin) met at Yalta in February 1945 and made it clear that Tito and Šubašić had to get on with it, King Peter gave in, and all the pieces fell into place. The regents were sworn in, as was the united government, and the British ambassador flew in. Maclean was finally able to leave.

Quotations

- When I got to Cairo, I took a taxi to the address at which I had been told to report. "Ah," said the villainous-looking Egyptian who drove me, when he heard the address. "You want Secret Service."

- (On a reconnaissance trip to occupied Benghazi.) We walked down the middle of the street arm in arm, whistling and doing our best to give the impression that we had every right to be there. Nobody paid the slightest attention to us. On such occasions it's one's manner that counts. If only you can behave naturally, and avoid any appearance of furtiveness, it is worth any number of elaborate disguises and faked documents.

- Clearly it was no easy task to transport several dozen vehicles and a couple of hundred men across 800 miles of waterless desert without attracting the attention of the enemy.

- Another truck full of explosives went up, taking with it all my personal kit. That was another two trucks gone. My equipment was now reduced to an automatic pistol, a prismatic compass and one plated teaspoon. From now onwards I should be travelling light.

- Our meal that night was on a more luxurious scale than anything that we had tasted for some time. In addition to the usual spoonful of bully beef, we used up some of the remaining water in making some hot porridge and brewed up some tea. We also scraped up enough rum for a small tot all round. This we drank after supper, lying on a little sandbank and watching the sun sinking behind the dunes. I cannot remember a meal that I enjoyed more or that seemed more wildly and agreeably extravagant. Extravagant it certainly was, for, when we had finished eating, there was no food left at all, and only enough water to half fill one water-bottle for each man.

- I was to have dinner that night with [Sir Alexander] Cadogan. As I lay in my bath, I reflected that the last time I had seen him had been in his room at the Foreign Office when I had handed him my letter of resignation from the Diplomatic Service. It seemed a long time ago. Looking back on the few but crowded years between, it occurred to me forcibly how fortunate I had been in my decision and how lucky not to miss the experiences which had fallen to my lot in the intervening space of time. To me, it was not disagreeable to look forward to a future of uncertainty and insecurity, with none of the slow inevitability of a career in the Government service; to feel myself, in however small a way, the master of my destiny. With my left foot I turned the hot-water tap full on and wallowed contentedly.

- The day after, I asked my pilot, a cheerful young New Zealander, if he thought we really needed an escort. He said that, unless we had bad luck, he could probably get away from anything except a very up-to-date fighter. I asked him if he would get into trouble if we went without an escort. He replied cheerfully that, if we came back safely, no one would say anything, and if we didn't, it wouldn't matter anyway. This seemed sound enough logic, and so we sent off a signal to Robin, announcing our arrival, and set off on our own.

- I was right: we had been dropped from very low indeed; no sooner had my parachute opened, than I hit the ground with more force than was comfortable.

See also

References

- ^ Obituary, The New York Times.

- ^ "Back to Benghazi" in Eastern Approaches

- Maclean, Fitzroy. Eastern Approaches (1999 reprint ed.). Penguin Global. ISBN 0-14-013271-6.

- Maclean Fitzroy. Eastern Approaches (1949 ed.) https://znaci.org/00001/1.pdf