Enceladus Life Finder

Enceladus Life Finder (ELF) is a proposed

Overview

The Enceladus Life Finder mission was first proposed in 2015 for Discovery Mission 13 funding,[2] and then it was proposed in May 2017 to NASA's New Frontiers program Mission 4,[4][5][6] but it was not selected.[7]

If selected at another future opportunity, the ELF mission would search for

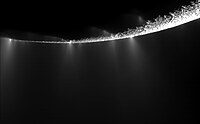

In 2008, the Cassini orbiter was flown through a plume and analyzed the material with its neutral

On 14 December 2023, astronomers reported the first time discovery, in the

Mission concept

The Enceladus Life Finder (ELF) mission would pursue the implications of

Objectives

The goals of the mission are derived directly from the most recent decadal survey: first, to determine primordial sources of organics and the sites of organic synthesis today; and second, to determine if there are current habitats in Enceladus where the conditions for life could exist today, and if life exists there now.[1] To achieve these goals, the ELF mission has three objectives:[1]

- To measure abundances of a carefully selected set of neutral species, some of which were detected by Cassini, to ascertain whether the organics and volatiles coming from Enceladus have been thermally altered over time.

- To determine the details of the interior marine environment — pH, oxidation state, available chemical energy, and temperature — that permit characterization of the life-carrying capacity of the interior.

- To look for indications that organics are the result of biological processes through three independent types of chemical measurements that are widely recognized as diagnostic of life.

Proposed scientific payload

The ELF spacecraft would use two

- mass spectrometerwith significantly improved performance over existing instruments, and optimized to analyze the gas expelled from the vents.

- Enceladus Icy Jet Analyzer (ENIJA), optimized to analyze solid particles expelled from the vents.

The

ELF's instruments would conduct three kinds of tests in order to minimize the ambiguity involved in life detection.

See also

- Abiogenesis

- Astrobiology

- Enceladus Orbilander

- Enceladus Explorer

- Enceladus Life Signatures and Habitability (ELSAH)

- Explorer of Enceladus and Titan (E2T)

- Europa Clipper

- Journey to Enceladus and Titan (JET)

- Life Investigation For Enceladus (LIFE)

- THEO

References

- ^ a b c d e f Lunine, Jonathan I.; Waite, Jack Hunter Jr.; Postberg, Frank; Spilker, Linda J. (2015). Enceladus Life Finder: The search for life in a habitable moon (PDF). 46th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2015). Houston (TX): Lunar and Planetary Institute.

- ^ a b c d Clark, Stephen (April 6, 2015). "Diverse destinations considered for new interplanetary probe". Space Flight Now. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ Battersby, Stephen (March 26, 2008). "Saturn's moon Enceladus surprisingly comet-like". New Scientist. Retrieved April 16, 2015.

- ^ Cofield, Calla (April 14, 2017). "Enceladus' Subsurface Energy Source: What It Means for Search for Life". Space.com.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (September 15, 2017). "Back to Saturn? Five Missions Proposed to Follow Cassini". The New York Times.

- PMID 28461387.

- ^ Glowatz, Elana (December 20, 2017). "NASA's New Frontier Mission Will Search For Alien Life Or Reveal The Solar System's History". IB Times.

- ^ a b c d e f Lunine, Jonathan I. "Searching for Life in the Saturn System: Enceladus Life Finder" (PDF). ELF Team. Lunar And Planetary Institute. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (December 14, 2023). "Poison Gas Hints at Potential for Life on an Ocean Moon of Saturn - A researcher who has studied the icy world said "the prospects for the development of life are getting better and better on Enceladus."". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 14, 2023. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- from the original on December 15, 2023. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ Gronstal, Aaron (July 30, 2014). "Enceladus in 101 Geysers". NASA Astrobiology Institute. Archived from the original on August 16, 2014. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ a b Witze, Alexandra (March 11, 2015). "Hints of hot springs found on Saturnian moon". Nature News. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ "Ocean Within Enceladus May Harbor Hydrothermal Activity". SpaceRef. March 11, 2015.

- ^ Platt, Jane; Bell, Brian (April 3, 2014). "NASA Space Assets Detect Ocean inside Saturn Moon". NASA. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- S2CID 28990283.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (April 3, 2014). "Saturn's Enceladus moon hides 'great lake' of water". BBC News. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ Anderson, Paul Scott (March 13, 2015). "Cassini Finds Evidence for Hydrothermal Activity on Saturn's Moon Enceladus". AmericaSpace. Retrieved April 7, 2015.