Microbiology

| Part of a series on |

| Biology |

|---|

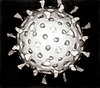

Microbiology (from

The existence of microorganisms was predicted many centuries before they were first observed, for example by the

History

The existence of microorganisms was hypothesized for many centuries before their actual discovery. The existence of unseen microbiological life was postulated by

In 1546,

In 1676,

Kircher was among the first to design magic lanterns for projection purposes, and so he was well acquainted with the properties of lenses.[16] He wrote "Concerning the wonderful structure of things in nature, investigated by Microscope" in 1646, stating "who would believe that vinegar and milk abound with an innumerable multitude of worms." He also noted that putrid material is full of innumerable creeping animalcules. He published his Scrutinium Pestis (Examination of the Plague) in 1658, stating correctly that the disease was caused by microbes, though what he saw was most likely red or white blood cells rather than the plague agent itself.[16]

The birth of bacteriology

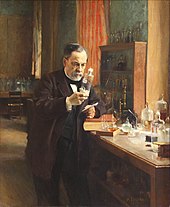

The field of

While Pasteur and Koch are often considered the founders of microbiology, their work did not accurately reflect the true diversity of the microbial world because of their exclusive focus on microorganisms having direct medical relevance. It was not until the late 19th century and the work of

Branches

The

Applications

While some people have

Bacteria can be used for the industrial production of

A variety of

Microorganisms are beneficial for

Research has suggested that microorganisms could be useful in the treatment of

Some bacteria are used to study fundamental mechanisms. An example of model bacteria used to study motility[37] or the production of polysaccharides and development is Myxococcus xanthus.[38]

See also

- Professional organizations

- American Society for Microbiology

- Federation of European Microbiological Societies

- Society for Applied Microbiology

- Society for General Microbiology

- Journals

References

- ^ "Microbiology". Nature. Nature Portfolio (of Springer Nature). Retrieved 2020-02-01.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-321-73551-5.

- ISBN 9781118960608.

- S2CID 4431143.

- PMID 7535888.

- ^ Rice G (2007-03-27). "Are Viruses Alive?". Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-26606-2.

- ISBN 978-81-208-1578-0.

- ^ Varro MT (1800). The three books of M. Terentius Varro concerning agriculture. Vol. 1. Charing Cross, London: At the University Press. p. xii.

- ^ "فى الحضارة الإسلامية - ديوان العرب" [Microbiology in Islam]. Diwanalarab.com (in Arabic). Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- S2CID 57857037.

- ^ Fracastoro G (1930) [1546]. De Contagione et Contagiosis Morbis [On Contagion and Contagious Diseases] (in Latin). Translated by Wright WC. New York: G.P. Putnam.

- ^ "RKI - Robert Koch - Robert Koch: One of the founders of microbiology".

- ^ PMID 25750239.

- S2CID 23998841.

- ^ PMID 12964250.

- ^ Drews G (1999). "Ferdinand Cohn, among the Founder of Microbiology". ASM News. 65 (8): 547.

- ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- PMID 12758285.

- S2CID 22211340.

- ^ Johnson J (2001) [1998]. "Martinus Willem Beijerinck". APSnet. American Phytopathological Society. Archived from the original on 2010-06-20. Retrieved May 2, 2010. Retrieved from Internet Archive January 12, 2014.

- ^ Paustian T, Roberts G (2009). "Beijerinck and Winogradsky Initiate the Field of Environmental Microbiology". Through the Microscope: A Look at All Things Small (3rd ed.). Textbook Consortia. § 1–14.

- PMID 23231482.

- PMID 20361283.

- ^ "Branches of Microbiology". General MicroScience. 2017-01-13. Retrieved 2017-12-10.

- ISBN 978-0321897398.

- )

- PMID 23317557.

- ISBN 978-1-904455-30-1. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- S2CID 21602792.

- ISBN 978-1-904455-36-3. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- ISBN 978-1-904455-17-2. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- PMID 10195977.

- ISBN 978-1-904455-01-1. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- ^ Wenner M (30 November 2007). "Humans Carry More Bacterial Cells than Human Ones". Scientific American. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-904455-38-7.

- S2CID 2340386.

- PMID 32516311.

Further reading

- Kreft JU, Plugge CM, Grimm V, Prats C, Leveau JH, Banitz T, et al. (November 2013). "Mighty small: Observing and modeling individual microbes becomes big science". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (45): 18027–18028. PMID 24194530.

- Madigan MT, Martinko JM, Bender KS, Buckley DH, Stahl DA (2015-06-05). Brock Biology of Microorganisms, Global Edition. Pearson Education Limited. ISBN 978-1-292-06831-2.

External links

Media related to Microbiology at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Microbiology at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Microbiology at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Microbiology at Wikiquote- nature.com Latest Research, reviews and news on microbiology

- Microbes.info is a microbiology information portal containing a vast collection of resources including articles, news, frequently asked questions, and links pertaining to the field of microbiology.

- Microbiology on In Our Time at the BBC

- Immunology, Bacteriology, Virology, Parasitology, Mycology and Infectious Disease

- Annual Review of Microbiology Archived 2009-01-20 at the Wayback Machine