London, Brighton and South Coast Railway

1920 map of the railway | |

The LB&SCR armorial device[note 1] | |

| Technical | |

|---|---|

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) |

| Length | 457 miles 20 chains (735.9 km) (1919)[1] |

| Track length | 1,264 miles 32 chains (2,034.9 km) (1919)[1] |

The London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR (known also as the Brighton line, the Brighton Railway or the Brighton)) was a railway company in the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1922. Its territory formed a rough triangle, with London at its apex, practically the whole coastline of

The LB&SCR was formed by a merger of five companies in 1846, and merged with the L&SWR, the SE&CR and several minor railway companies in southern England under the

Origins of the company

The London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR) was formed by

- The London and Croydon Railway (L&CR), created in 1836 and opened in 1839.

- The London and Brighton Railway (L&BR), created in 1837 and opened in 1841.

- The Brighton and Chichester Railway, created in 1844 and opened in stages between November 1845 and June 1846, with an extension to Havant under construction at the time of amalgamation.

- The Brighton, Lewes and Hastings Railway, created in February 1844, opened in June 1846.

- The Croydon and Epsom Railway, created in July 1844, under construction at the time of amalgamation.

Only the first two were independent operating railways: the Brighton and Chichester and the Brighton, Lewes and Hastings had been purchased by the L&BR in 1845,[2] and the Croydon and Epsom was largely owned by the L&CR.)

The amalgamation was brought about, against the wishes of the boards of directors of the companies, by shareholders in the L&CR and L&BR who were dissatisfied with the early returns from their investments.[3]

The LB&SCR existed for 76 years until 31 December 1922, when it was wound up as a result of the

Original routes

(Dates of opening from F. Burtt The Locomotives of the London Brighton and South Coast Railway 1839–1903.[4])

At the time of its creation the LB&SCR had around 170 route miles (274 km) in existence or under construction, consisting of three main routes and a number of branches.

The

The

The

A short line from New Cross to Deptford Wharf, proposed by the L&CR, was approved in July 1846, shortly before amalgamation, but was not opened until 2 July 1849. The use of this line for passengers would have contravened the recently negotiated agreement with the SER that the LB&SCR would not operate lines to the east of its main line, and it was restricted to goods.[5] A short branch from this line to the nearby Surrey Commercial Docks in Rotherhithe opened in July 1855.[6]

London stations

The main London terminus was the L&CR station at

The LB&SCR inherited from the L&CR running powers to the smaller SER passenger terminus at Bricklayers Arms. Poorly sited for passengers, it closed in 1852 and was converted into a goods station.

The LB&SCR owned three stations at Croydon, later East Croydon (former L&BR) Central Croydon and West Croydon (former L&CR).

Atmospheric lines

The L&CR had been partially operated by the atmospheric principle between Croydon and Forest Hill, as the first phase of a scheme to use this mode of operation between London and Epsom. However, following a number of technical problems, the LB&SCR abandoned atmospheric operation in May 1847. This enabled it to build its own lines into London Bridge, and have its own independent station there, by 1849.

The history of the LB&SCR can be studied in five distinct periods.

Relations with neighbouring railways, and the beginnings of expansion 1846–1859

The LB&SCR was formed at the same time as the bursting of the

In 1847 the naval dockyard of

In 1853 the Direct Portsmouth Railway gained parliamentary authority to build a line from Godalming to Havant with the intention of the company selling itself either to the L&SWR or the LB&SCR. This scheme would provide a far more direct route to Portsmouth but involved sharing the LB&SCR tracks for the five miles (8 km) between Havant and the joint line to Portsea.[10] The LB&SCR objected to the scheme but the L&SWR negotiated with the new company and in December 1858 sought to operate a train over the new route. The LB&SCR attempted to prevent the use of its tracks and the so-called 'battle of Havant' ensued. The matter was eventually resolved in the courts in August 1859, and relations between the railways were formalized in agreements of 1860 and 1862.[11]

Samuel Laing had also approved a modest degree of expansion elsewhere, most notably the acquisition of a

Crystal Palace Branch

Some of the directors of the LB&SCR were closely involved with the company that purchased

Rapid expansion 1856–1866

Samuel Laing retired as chairman at the end of 1855 to pursue a political career, and was replaced by the

West End of London

Schuster also encouraged an independent concern, the West End of London and Crystal Palace Railway (WEL&CPR), to construct a new line extending in a wide arc round south London from the LB&SCR Crystal Palace branch to Wandsworth in 1856 and to Battersea in 1858 with a temporary terminus at Battersea Pier. Shortly after this line was completed, the LB&SCR leased it from the WEL&CPR and incorporated it into its system.

Between 1858 and 1860 the LB&SCR was a major shareholder in the

New lines in South London

The VS&PR line was also connected with another joint venture the

The

At the same time, the LB&SCR was cooperating with the LC&DR to create the

New lines in Sussex

During 1858, a

In West Sussex the

Following the 1862 agreement with the L&SWR, a line was built from near Pulborough to a junction with the

New lines in Surrey

The

The LB&SCR wished to connect Horsham with significant towns in Surrey, and in 1865 it opened a line between West Horsham and the L&SWR near Guildford. It constructed a line from Leatherhead to Dorking in March 1867, continued to Horsham two months later. This enabled alternative LB&SCR routes from London to Brighton and the West Sussex coast and further reduced the distance of its route from London to Portsmouth.

The LB&SCR supported the independent Surrey and Sussex Junction Railway, which obtained powers in July 1865 to build a line from Croydon to Tunbridge Wells via Oxted, to be worked by the LB&SCR. The involvement of LB&SCR directors in this scheme was interpreted by the SER as a breach of the 1849 agreement, and in retaliation the SER and LC&DR obtained Parliamentary approval to build a rival 'London, Lewes and Brighton Railway', which would undermine the profitable LB&SCR monopoly to that town.[21] Neither scheme was proceeded with.

Newhaven Harbour

Following the opening of the branch from

Growth of the London suburbs

Largely as a result of the railway, the rural area between

As part of its suburban expansion, the LB&SCR built a

Deterioration of relations with the SER

Relations between the LB&SCR and the SER and the interpretation of the 1848 agreement continued to be difficult throughout the 1850s and 1860s. They reached a low point in 1863 when the SER produced a report for its shareholders outlining a long list of the difficulties between the two companies, and the reasons why they considered that the LB&SCR had broken the 1848 agreement.[25]

The main areas of disagreement listed were at

The most flagrant example of the lack of cooperation between the two companies, however, was with respect to the independent

The chronic congestion over the shared line between

1867 financial crisis and its impact

The collapse of the bankers Overend, Gurney and Company in 1866 and the financial crisis the following year brought the LB&SCR to the brink of bankruptcy.[29] A special meeting of shareholders was adjourned, and the powers of the board of directors were suspended pending receipt of a report into the financial affairs of the company and its prospects.[30] The report made clear that the LB&SCR had overextended itself with large capital projects sustained by profits from passengers, which suddenly declined as a result of the crisis. Several country lines were losing money – most notably between Horsham and Guildford, East Grinstead and Tunbridge Wells, and Banstead and Epsom – and the LB&SCR was committed to building or acquiring others with equally poor prospects.[31] The report was extremely critical of the policies of Schuster and the company secretary, Frederick Slight, both of whom resigned. It did however point out that these lines had been built or acquired as a means for preventing competition from neighbouring railways. The committee recommended the abandonment of several projects, and that the LB&SCR should enter into a working agreement with the SER.

The new board of directors accepted many of these recommendations, and they managed to persuade Samuel Laing to return as chairman. It was through his business acumen and that of the new secretary and general manager J. P. Knight that the LB&SCR gradually recovered its financial health during the early 1870s.[32]

As a result, all construction of lines was suspended. Three important projects then under construction were abandoned: the

The proposed 'working cooperation' with the SER never took effect but remained under active consideration by both parties, and later involved the LC&DR.[34] It was not until 1875 that the idea was dropped, after the SER pulled out of negotiations due to the conditions imposed by Parliament on the proposed merger. The LB&SCR continued as an independent railway but the SER and LCDR eventually formed a working relationship in 1899 with the formation of the South Eastern and Chatham Railway.

One new line to which the LB&SCR was committed was the

Later 19th century

By the mid-1870s the LB&SCR had recovered its financial stability through a policy of encouraging the more intensive use of lines and reducing operating costs. Between 1870 and 1889 annual revenue rose from £1.3 million to £2.4 million, whilst its operating costs rose from £650,000 to just over £1 million.[35] The LB&SCR was able to embark upon new railway building and improvements to infrastructure. Some new lines passed through sparsely populated areas and merely provided shorter connections to towns that were already on the railway network, and so were unlikely to be profitable, but the LB&SCR found itself under pressure from local communities wanting a rail connection, and was frightened that they would otherwise be developed by rivals.

The main reason for the financial recovery lay in the exploitation of London suburban traffic. By the late 1880s the LB&SCR had developed the largest suburban network of any British railway, with 68 route miles (109 km) in the suburbs in addition to its main lines, in three routes between London Bridge and Victoria:

New routes and station improvements

The scheme to link Eastbourne with Tunbridge Wells was revived in April 1879 with the opening of a line connecting the Hailsham branch to

In 1877 authority was granted to the Lewes and East Grinstead Railway (L&EGR), roughly parallel to the 'Cuckoo Line',[38] sponsored by local landowners, including the Earl of Sheffield, and including a branch from Horsted Keynes to Haywards Heath on the Brighton main line. A year later an act of 1878 enabled the LB&SCR to acquire and operate lines, opened in August 1882 and September 1883. The East Grinstead–Lewes line subsequently became known as the 'Bluebell line' and, following its closure in 1958, the section between Horsted Keynes and Sheffield Park was taken over by the Bluebell Railway Preservation Society.

The LB&SCR in West Sussex was largely complete by 1870 except for a link between Midhurst and Chichester, delayed by the financial crisis of 1867; this was revived and opened in 1881. Minor improvements around Littlehampton were made, and a branch to Devil's Dyke opened in 1887, built by and owned by an independent company but operated by the LB&SCR. In Hampshire the LB&SCR leased the Hayling Island branch line from 1874,[39] opened in 1865 as an independent concern.[40] The LB&SCR and the L&SWR jointly built a 1+1⁄4-mile (2 km) branch from a new station on their existing joint line at Fratton to East Southsea in 1887, but early in the 20th century had to compete with a tramway, and it was closed at the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914.[41]

Although the proposed Surrey and Sussex Junction Railway had been abandoned in 1867, there remained a demand from Croydon to towns such as East Grinstead, Tunbridge Wells and the East Sussex coast. The SER was looking for a relief route in the same general direction for its Tonbridge and Hastings services, and the two railways collaborated in a joint line between South Croydon, on the main Brighton line, and Oxted. Beyond Oxted, the LB&SCR would build its own lines to link with the Bluebell line at East Grinstead and its line to Tunbridge Wells. SER trains would join the line between Redhill and Tonbridge. Authority was granted in 1878 and they opened in 1884.

Brighton railway station was rebuilt and extended in 1882–83 with a new single roof, and Eastbourne was rebuilt in 1886 to cope with additional traffic.

Congestion and slow trains

With the steady growth of traffic in the South London suburbs during the 1880s and early 1890s, the LB&SCR was the subject of press criticism for poor timekeeping and slow trains,[42] although it was never subjected to the levels of press and public obloquy accorded to the SER. Two of the reasons for poor timekeeping were the volume of traffic generated and the complexity of the LB&SCR network north of Redhill with large numbers of junctions and signals.[43] A further complication was that both the LB&SCR and the SER shared the 11 miles (18 km) of track between Redhill and East Croydon. This part of the line was owned by the SER, which (according to Acworth) gave its trains precedence through the junctions at Redhill,[44] but the LB&SCR paid an annual fee of £14,000 for its use. Relations with the SER began to deteriorate once more and eventually both companies appointed Henry Oakley general manager of the Great Northern Railway as an independent assessor in 1889. Oakley supported the LB&SCR right to use the line but increased the annual payment to £20,000.[28] However this did not solve the problem and an 1896 study of LB&SCR passenger services, by J. Pearson Pattinson described the 8+1⁄4 miles (13.3 km) of shared track between Redhill and Stoats Nest (Coulsdon) as being 'in a state of the utmost congestion, and detentions of the Brighton expresses, blocked by South Eastern stopping trains, are as constant as irritating.'[45]

Quarry line

Ultimately the only solution was for the LB&SCR to build its own line between

20th century

During its last 20 years the LB&SCR opened no new lines, but invested in improving its main line and London terminals, together with the electrification of its London suburban services.

Following the completion of the Quarry line, the bottleneck on the heavily used main line moved further south. Plans were drawn up for the quadrupling throughout, but only the 16 miles (26 km) from Earlswood to Three Bridges were completed, between 1906 and 1909. A fifth track was laid between Norwood Junction and South Croydon in 1907–08. Extension beyond Three Bridges would have involved heavy engineering at Balcombe tunnel, over the Ouse Valley Viaduct and through the South Downs. The required capital expenditure was diverted to extending the electrification programme.

Unlike other mainline railway companies, the LB&SCR had to share both its London termini with its rivals,

Motive power shortage

Between 1905 and 1912 the LB&SCR suffered an increasingly serious motive power shortage due to the inability of

The First World War

With other British railways the LB&SCR was brought under government control during the

Newhaven harbour also received casualties landing in hospital ships, with the railway providing ambulance trains.[52] There were several army camps within the territory of the LB&SCR which therefore provided 27,366 troop trains.[51] Army horses awaiting shipping to France were stabled at Farlington Racecourse.[53]

At the outbreak of hostilities the area surrounding Newhaven Port was requisitioned and the Harbour station closed. From 22 September 1916 Newhaven became a special military area for handling Government traffic under the Defence of the Realm Regulations.[54]

This additional traffic required substantial improvements to infrastructure, notably at Newhaven harbour, where additional warehousing, new sidings and signalling constructed and electric lighting was installed. When Newhaven became overwhelmed the tidal port of Littlehampton was rebuilt and pressed into service.[55] Inland, a much enlarged goods marshalling yard was established at Three Bridges, which was chosen as a nodal point for handling War traffic. At Gatwick and Haywards Heath, passing loops were constructed so that the frequent passenger trains would not be impeded by slower goods trains and to hold munitions trains during air raids. Some munitions trains were routed to Newhaven via the Steyning Line to Brighton to avoid congesting the part of the Brighton main line which had only two tracks. Between 1914 and 1918, 5,635 members of LB&SCR staff joined the forces, creating staff shortages at all levels (including the Chief Mechanical Engineer who was called up for service in Russia and Roumania).[56] This necessitated the employment of female labour in clerical grades and for carriage cleaning.[57] The railway erected a War Memorial at London Bridge in 1920 honouring the 532 staff who had lost their lives. Likewise, in April 1922, the last locomotive to be constructed by the company, 4-6-4T 'L' Class No. 333, was named 'Remembrance' and carried a memorial plaque.[58]

LB&SCR at Grouping

By 31 December 1922, when the LB&SCR ceased to have an independent existence, it had 457 miles (735 km) of route. Of these, 100 mi (161 km) was single track, 357 mi (575 km) double track, 47 mi (76 km) triple track, and 49 mi (79 km) four or more tracks. Sidings had a total length of 355 miles (571 km).[59] According to Bonavia, 'the Brighton was a highly individual line in its strengths and weaknesses, it was to experience drastic changes under Southern [Railway] management which older members of the staff would not always accept gracefully.'[60]

Train services

The LB&SCR was essentially a passenger-carrying concern, with goods and mineral traffic playing a limited role in its receipts. As originally envisaged the railway was a trunk route, conveying passengers (and to a lesser extent goods) between London, Croydon and the south coast, with relatively little traffic to and from stations in between. However, the railway's existence began to generate new goods and passenger traffic at towns and villages on or near the main line, such as

The speed and punctuality of many LB&SCR passenger services was the subject of widespread criticism in the technical and popular press during the 1890s.[61] This was in part due in part to the complexity of the system between London and Croydon, with a large number of signals and junctions, the sharing of stretches of line with the SER, and the relatively short routes, which gave little opportunity to make up for lost time. The LB&SCR gradually began to rebuild its reputation during the 20th century through improvements to mainline infrastructure and electrification of suburban services.

Express passenger services

The company had no long-distance express trains, with a maximum journey length of 75 miles (121 km). Nevertheless, frequent express passenger services ran to the most important coastal destinations from both London Bridge and Victoria. Season ticket revenue, particularly from Brighton to London, was the backbone of the LB&SCR's finances for most of the 19th century.[62] The morning rush hour business services were among "the heaviest express services in the world" in the 1880s, with loads of 360 tons.[44]

Individual Pullman cars were introduced to Britain on the Midland Railway in 1874, followed by the Great Northern Railway soon after and the LB&SCR in 1875.[63] The LB&SCR pioneered all-Pullman trains in England, the Pullman Limited Express on 5 December 1881. It consisted of four cars built at the Pullman Car Company workshops in Derby, Beatrice, Louise, Maud and Victoria, the first electrically lit coaches on a British railway. The train made two down and two up trips per day, one each way on Sundays. It was renamed the Brighton Pullman Limited in 1887, and first-class carriages were attached. A new train was built in 1888: three Pullmans were shipped over in parts from the Pullman Palace Car Company in America, and assembled by the LB&SCR at Brighton.

The Brighton Limited was introduced on 2 October 1898. It ran only on Sundays, and not in July–September. It was timed to make the journey from Victoria in 60 minutes: "London to Brighton in one hour" was the advertisement used for the first time. On 21 December 1902 it made a record run of 54 minutes. It hit the headlines again when, faced with the threat of a competing electric railway being built from London to Brighton, it ran to Brighton in 48 minutes 41 seconds and the return to London in 50 minutes 21 seconds, matching the schedule put forward by the promoters of the electric line.

Stopping trains

Slower passenger services between London and the south coast often divided at East Croydon to serve both the London termini, and combined there for down trains, so East Croydon had an important nodal function in the system.[64] After 1867, following the opening of the direct line to Horsham, Sutton acted as a similar node for passenger trains between London and Portsmouth.

Slip coaches

The LB&SCR appears to have invented the practice of slipping coaches from the rear of express trains at intermediate stations for onward transmission to branch lines or smaller stations on the main line. The earliest recorded example was at Haywards Heath in February 1858, where coaches for Hastings were slipped from a London–Brighton express.[65] The slipping was coordinated by a series of communication bell signals between the guards on the two portions of the train and the locomotive crew.[66]

Before 1914, twenty-one coaches were slipped each day on the Brighton main line.[67] Coaches were slipped at Horley and Three Bridges for stations to East Grinstead, Forest Row and Horsham, or at Haywards Heath for stations to Brighton and Eastbourne. The practice continued until the electrification of the main line in 1932.[68]

London suburban traffic

After 1870, the LB&SCR greatly encouraged commuters into London by reducing the prices of season tickets and introducing special

Excursion and holiday traffic

Excursion trains from London to the South Coast and the Sussex countryside had been introduced in 1844,[71] and were a feature of the LB&SCR throughout its existence. Special fares to Brighton and other south coast resorts on summer Sundays and at bank holidays were regularly advertised in the press. Likewise, special trains serving the regular fetes and exhibitions at Crystal Palace during the summer months.

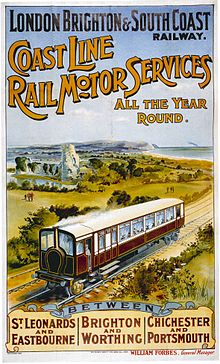

After 1870 the LB&SCR sought to develop the holiday and excursion trade and market other south coast resorts such as Hayling Island and the Isle of Wight as holiday destinations, by publishing a range of attractive posters. On the Isle of Wight the LB&SCR and the L&SWR jointly took over the ferry service from Portsmouth and built new pier at Ryde with a short line to the station at St John's Road in 1880. During the 1900s the company ran special Sunday trains to enable London cyclists to explore the Sussex and Surrey countryside.[72] By 1905 the railway was offering day trips to Dieppe and circular tickets, valid for a month, to enable Londoners to explore towns along the South Coast.[73]

In 1904 the Great Western Railway inaugurated holiday trains during the summer months from Birkenhead to Brighton and Eastbourne, in conjunction with the LB&SCR. The following year LB&SCR and L&NWR jointly operated the Sunny South Special from Liverpool and Manchester to these destinations. These trains operated via the West London lines, with the LB&SCR responsible for their operation from Kensington or Willesden.[74]

The LB&SCR served important Horse racing tracks at Brighton, Epsom, Gatwick, Goodwood, Lewes, Lingfield and Plumpton, and Portsmouth Park (Farlington). Race day special trains were an important source of revenue during the summer months.[75]

Rail motor services

During the first few years of the 20th century the LB&SCR, in common with other railways, became concerned about losses on branch and short-distance passenger services, particularly in winter. The L&SWR and the LB&SCR boards decided to investigate the use of steam powered railcars on the 1+1⁄4-mile (2 km) joint branch line between Fratton and East Southsea, in June 1903. The locomotive and carriage units were both built by the L&SWR, but one of the carriages was painted in the LB&SCR livery. The two vehicles had to be quickly withdrawn as they were found to be chronically underpowered, but were rebuilt with larger boilers and thereafter gave adequate service. However, their use did not stem the loss of traffic to the roads and in 1914 the branch was closed.[76]

Nevertheless, the LB&SCR directors asked the Chief Mechanical Engineer,

During the experiments relating to railcars and motor trains, the LB&SCR constructed unmanned halts, such as

Freight services

Freight represented a relatively small part of the LB&SCR's finances during its first half century. Agricultural goods and general merchandise were carried, together with wine, foodstuffs and manufactured goods imported from France. During the 1870s the pattern of goods services slowly began to change, leading to rapid growth in the 1890s, 'caused by the transport of raw materials and finished products of entirely new industries such as petroleum, cement, brick and tile manufacture, forestry and biscuit making.'[79] This resulted in the construction of 55 goods locomotives of the C2 class

There were no coal mines within LB&SCR territory, and so it had to pay substantially more for its fuel than most other companies.[80] The bulk of its coal was brought in 800 long tons (810 t) trains from Acton yard on the Great Western Railway to Three Bridges for redistribution, and the LB&SCR kept two goods locomotives at the GWR Westbourne Park Depot for this purpose.[81] In 1898 there was a scheme to develop Deptford Wharf for the landing of coal by sea.[82] The additional fuel costs were partially offset by the sale of shingle for rail ballast from Pevensey.[83]

The main London goods depot was at 'Willow Walk', part of the

Electrification

Proposals for a London and Brighton Electric Railway made to Parliament in 1900 failed to proceed, but caused the LB&SCR to consider

Although the

The first section was the

Continued success and profitability of its earliest projects caused the LB&SCR to decide to electrify all remaining London suburban lines in 1913. However, the outbreak of war the following year delayed what was planned to have been considerable further mileage of electrified line. By 1921 most of the inner London suburban lines were electrified, and during 1922 lines to Coulsdon and Sutton, opened on 1 April 1925. During 1920 plans were drawn up to extend the 'Elevated Electric' to Brighton, Worthing, Eastbourne, Newhaven and Seaford, and to Epsom and Oxted, but these were overtaken by the Grouping.[94]

The 'Elevated Electric' proved to be a technical and financial success,[95] but was short-lived since the L&SWR had adopted the third-rail system: its mileage far exceeded that of the LB&SCR. In 1926 the Southern Railway announced that, as part of a huge electrification project, all overhead lines were to be converted to third rail, thus bringing all lines into a common system. The last overhead electric train ran on 22 September 1929.[89][96]

Accidents and signalling control

Semaphore signalling and signal boxes were first introduced on the L&CR and had been adopted by the L&BR as early as the 1840s. There were a number of serious accidents in the early years of the LB&SCR, some due to failures in communication.[97] The LB&SCR began to improve its safety record in the 1860s with the introduction of interlocking,[98] and the early introduction of Westinghouse air brakes. Given the large number of junctions and the intensive use of its system, the LB&SCR maintained a good safety record during the last half century of its existence.

The following accidents occurred on the LB&SCR:

- On 6 June 1851, there was a derailment at Falmer Bank, East Sussex due to an object on the line.[99]

- On 27 November 1851, passenger train from Brighton ran into the eighth wagon of a goods train that had just left Ford, station, West Sussex, due to the passenger train passing a signal at danger.[100]

- On 17 March 1853, the boiler of locomotive No. 10 exploded at Brighton, East Sussex.[101]

- On 27 August 1853, confusion over a warning signal at New Cross caused a goods train to collide with an empty passenger train, resulting in the death of a fireman[102]

- On 21 August 1854, there was an accident at East Croydon, Surrey due to numerous causes, resulting in three fatalities and eleven injured.[103]

- On 3 October 1859, the boiler of a locomotive exploded at Falmer Incline.[104]

- On 25 August 1861, in the accident known as the Clayton Tunnel rail crash, an excursion train ran into the rear of another inside Clayton Tunnel, West Sussex due to a combination of the failure of an automatic signal to return to 'danger' and culpable operating errors. At the time, this was the deadliest accident up to that time in the United Kingdom with 23 killed and 176 injured.[105]

- On 29 May 1863, there was a derailment at Streatham Common, Surrey. Four people (including the driver) were killed 59 people were injured.[106]

- On 23 June 1869, two trains collided at New Cross Gate, Surrey due to driver error, excessive speed and guard error, injuring 91 people.[107]

- On 27 September 1879, the boiler of a locomotive exploded at Lewes, East Sussex. One person was killed and two were injured.[108]

- On 1 May 1891,in the accident known as the cast-iron bridge collapsed under a train at Norwood Junction, Surrey. Six people were injured.[109]

- On 23 July 1894, a brake van next to the engine hauling the 6.35pm from Havant derailed at Farlington Halt railway station and the first two coaches overturned.[110] The guard on the train was killed and seven passengers were injured.

- On 1 September 1897, a passenger train derailed near Heathfield, East Sussex. One person was killed.[111]

- On 23 December 1899, a Brighton train passed a signal at danger and ran into the back of a boat train express in thick fog at Keymer Junction, West Sussex. There were six fatalities and 20 injured.[112]

- In 1904, a freight train hauled by D1 class No. 239 Patcham was derailed at Cocking, West Sussex.[111]

- On 29 January 1910, an express passenger train became divided and was derailed at Stoat's Nest, Surrey due to a defective wheelset on a carriage. Seven people were killed and 65 were injured.[113]

- On 21 October 1913, 7 labourers were working a night shift at London Bridge station, scraping and cleaning the cradles and insulator fittings of the overhead line equipment. The wire brush of one of the men, labourer Amos Boniface, touched one of the electrical wires and he suffered severe burns. Boniface died 19 days later from his injuries.[114]

- On 3 April 1916, a passenger train was derailed between

- On 18 April 1918, a freight train became divided, the rear part coming to rest inside Redhill Tunnel, Surrey. Due to a signalman's error, another freight train ran into the wagons and was derailed. A third freight train ran into the wreckage.[115]

Signalling and signal boxes

The LB&SCR originally used semaphore for home signals and 'double disc' for distant signals, but after 1872 semaphore signals were used for both purposes.

The LB&SCR was using primitive interlocking between signals at some junctions by 1844.

The LB&SCR inherited the world's first signal boxes, at Bricklayers Arms Junction and Brighton Junction (Norwood). After 1880 it gradually developed its own architecture for signal boxes, using home-produced and contractor-built frames. J. E. Annett, the inventor of Annett's key in 1875, a portable form of interlocking, was a former LB&SCR employee.

During the remodelling of

Rolling stock

For the greater part of its existence the LB&SCR relied upon

The LB&SCR under Stroudley was one of the first railways in Britain to adopt the Westinghouse air brake after 1877[121] in preference to the far less effective vacuum brakes employed by its neighbours.

Steam locomotives

The LB&SCR inherited 51 steam locomotives from the

The LB&SCR achieved early fame as the first railway to use the

Stroudley reduced this to 12 main classes, many with interchangeable parts, by 1888.

Stroudley's successor

The last

LB&SCR locomotive designs had little impact on the locomotive policy of the Southern Railway after 1923 because they were built to a more generous

Electric traction

The electrified lines were operated by

Coaching stock

The jobs of

The appointment of Albert Panter as Carriage and Wagon Works Manager under Robert Billinton in 1898 (Carriage and Wagon Superintendent from 1912) led to the introduction of bogie carriages for mainline trains in 1905,[132] but suburban services were operated by six-wheeled "block trains" with solid wooden buffers, permanently tight coupled in sets of ten or 12.[133] Many of these were still in use at grouping in 1923. Better vehicles appeared early in the 20th century with the 'Balloon stock' and electric stock.[134]

Sixteen carriages of LB&SCR origin have been preserved, including one luxurious "Directors' saloon" of 1914: these are principally on the Bluebell Railway and the Isle of Wight Steam Railway.[135] A number of grounded carriage bodies used as holiday homes survive.

Wagons

Sixteen wagons formerly in LB&SCR ownership now survive, largely because the Southern Railway transferred them to the Isle of Wight, where they remained in use until the 1960s.[136]

Liveries

After 1870 the LB&SCR was renowned for the attractiveness of its locomotives and coaching stock and condition of its country stations. "No company, even the North-Western itself turns out smarter looking trains than the Brighton main line expresses and even some of the suburban trains."[137]

Between 1846 and 1870 passenger locomotives were painted

From 1870 to 1905 the livery was Stroudley's famous Improved Engine Green, a golden

From 1905 to 1923 front-line express locomotives were a dark shade of umber. Lining was black with a gilt line either side. Cab roofs remained white. Frames were black, wheels umber, and buffer beams returned to signal red. The company's initials were painted on the tender- or tank-sides (initially 'L.B.& S.C.R.', but after 1911 the ampersand and the R were removed) in gilt. Secondary passenger locomotives had the same livery, but instead of gilt lining chrome yellow paint was used. Goods engines were gloss black with double vermilion lining. Names and numbers were in white letters with red shading. Carriages were initially all olive green with white lining and detailing. From 1911 this changed to plain umber with black lettering picked out with gold shading.

Ferry services and ships

The LB&SCR invested in cross-channel ferry services, initially from Shoreham to Dieppe. Following the opening of the line to

The

In 1863, the LB&SCR transferred the Jersey service to Littlehampton and soon afterwards established another between Littlehampton and Honfleur.

By 1880 lines connected the Ryde Pier and the Portsmouth Harbour ferry terminals. It was therefore a natural progression for the companies to acquire the ferry routes. To do this the LB&SCR and the L&SWR formed the South Western and Brighton Railway Companies Steam Packet Service (SW&BRCSPS), which bought the operators.[23]

In 1884 the Isle of Wight Marine Transit Company started a goods rail ferry between the

The LB&SCR operated a significant number of ships in its own right, jointly with

Structures, buildings and civil engineering

The LB&SCR inherited significant structures, buildings and other civil engineering features, including:

- Bridges and Viaducts – the London Road viaduct, the Lewes Road viaduct Moulsecoomb.

- The Norwood Junction flyover, the world's first railway overpass.

- Tunnels – Merstham, Balcombe, Haywards Heath, Clayton and Patcham, Ditchling Road (Brighton) and Falmer

- Stations – Modular station buildings at .

Stations

The LB&SCR inherited or built 20 termini, the most significant at

.The use of Mocatta's modular station designs was not perpetuated. During the 1850s and 1860s most stations were constructed according to one or two stock designs prepared by the Chief Engineers, R. Jacomb-Hood and Frederick Banister (1860–1895). Banister had a love of Italianate architecture, meaning that during the 1880s the LB&SCR produced elaborate decorated architecture for many country stations, notably on the Bluebell and Cuckoo Lines.[142] The architect was Banister's son-in-law, Thomas Myres.[143]

Workshops and motive power depots

The L&BR established a repair workshop at Brighton in 1840. Between 1852 and 1957 more than 1,200 steam locomotives and prototype diesel electric and electric locomotives were constructed there, before closure in 1962. It had small locomotive repair facilities at New Cross and Battersea Park Depots in London.

By the first decade of the 20th century, Brighton works could no longer cope with the repair and building of both locomotives and rolling stock. In 1911 the LB&SCR built a carriage and wagon works at

There were

The headquarters and main offices were at

Hotels

The LB&SCR opened the Terminus Hotel at London Bridge and the Grosvenor Hotel at Victoria in 1861. The first of these was not successful due to its site on the south bank and was turned into offices for the railway in 1892. It was destroyed by bombing in 1941. The Grosvenor Hotel was rebuilt and enlarged in 1901.[146] The LB&SCR acquired the Terminus Hotel next to Brighton station in 1877,[147] and operated the London and Paris Hotel at Newhaven.[148]

The LB&SCR as an investment

The 1867 report by the railway found that there had been 'a reckless disregard for shareholders' interests for many years.'.[149] As a result, the company policies were several times subjected to criticism in pamphlets published during the 1870s and 1880s.[150] The matter was settled in 1890 when the economist and editor of the Financial Times, William Ramage Lawson, conducted a detailed analysis of the financial performance and prospects of the LB&SCR, comparing it with other British railways. He concluded that the Brighton Deferred stock 'combined the highest return on investment, with the best prospect of future appreciation and the smallest risk of retrogression.'[151] Among the reasons given for this opinion were:

- Well established route and freedom from competition

- Varied and well distributed sources of traffic

- Moderate working expenses due to high quality construction of the original route and good maintenance.

- Energetic and prudent management

From 1870 the LB&SCR appears to have been a well-run, enterprising and profitable railway for its shareholders.

Notable people

Chairmen of the board of directors

- Charles Pasco Grenfell (1846–1848)

- Samuel Laing (1848–1855)

- Leo Schuster (1856–1866)

- Peter Northall Lawrie (1866–1867)

- Sir Walter Barttelot (April – July 1867)

- Samuel Laing (again, 1867–1896)

- Lord Cottesloe (1896–1908)

- Earl of Bessborough (1908–1920) – died in office

- Charles C. Macrae (1920–1922)

- Gerald Loder (December 1922)

Members of the board of directors

- John Pares Bickersteth[152]

- Rear-Admiral The Hon. Thomas S. Brand[152]

- Major Philip Cardew[152]

- Dudley Docker

- Sir Julian Goldsmid

- William Milburn[152]

- Lord Henry Nevill[152]

- John Nix

- Sir Arthur Otway, 3rd Baronet – Deputy-Chairman in 1905[152]

- Sir Spencer Walpole[152]

Managers

- Peter Clarke(1846–1848) – Manager

- George Hawkins (1849–1850) – Goods Manager

- ? Pountain (1849–1850) – Non Goods Manager

- George Hawkins (1849–1850) – Traffic Manager

- John Peake Knight(1869–1870) – Traffic Manager

- John Peake Knight(1870–1886) general manager

- Sir Allen Sarle (1886–1897) general manager

- John Francis Sykes Gooday (1897–1899) general manager

- William de Guise Forbes(1899–1922) general manager

Secretaries

- T.J. Buckton (1846–1849)

- Frederick Slight (1849–1867)

- Sir Allen Sarle (1867–1898) from 1886 to 1898 also general manager

- J.J. Brewer (1898–1922)

Chief engineers

- Robert Jacomb-Hood (1846–1860)

- Frederick Banister (1860–1895)

- Charles Langbridge Morgan (1895–1917)

- J.B. Ball (1917–1920)

- O.G.C. Drury (1920–1922)

Locomotive superintendents

- John Gray (1846–1847)

- Thomas Kirtley (February–November 1847) – died in office

- John Chester Craven (1847–1870)

- William Stroudley (1870–1889) – died in office

- R. J. Billinton (1890–1904) – died in office

- D. E. Marsh (1905–1911)

- L. B. Billinton (1912–1922)

Carriage and wagon superintendent

- Albert Panter (1912–1922)

Fireman

- Curly Lawrence known as LBSC, one of Britain's most prolific and well known model or scale-steam-locomotive designers, was employed as a fireman on the LB&SCR as a young man, and took the shortened version of its initials as his pseudonym.

Industrial relations

For its time, the LB&SCR was regarded as a good employer. In 1851 it created a benevolent fund for staff who had become incapacitated, and from 1854 operated a savings bank. In 1867 there was a two-day strike involving the

Labour relations between the railway management, locomotive crews and Brighton works staff declined markedly in the period 1905 and 1910 leading to several strikes and sackings.[155] This was partly due to increased union militancy and to the intransigency of the Locomotive Superintendent Douglas Earle Marsh. This situation improved under Marsh's successor.

See also

- List of early British railway companies

- Locomotives of the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway

- List of LB&SCR ships

Notes

- ^ The cross and sword (top) represents London, the two dolphins (bottom) Brighton, the three half-lions half-ships (right) the Cinque Ports, and the star and crescent (left) Portsmouth.

References

- ^ a b The Railway Year Book for 1920. London: The Railway Publishing Company Limited. 1920. p. 189.

- ^ White (1961), pp. 84, 99.

- ^ Turner (1977), pp. 253–71.

- ^ Burtt (1975), 19.

- ^ Turner (1978), p. 34.

- ^ Turner (1978), p. 65.

- ^ Turner (1978), p. 23.

- ^ Sekon (1895), pp. 12–14.

- ^ a b Turner (1976), p. 29.

- ^ Turner (1976), pp. 79–82.

- ^ Turner (1976), 82–84.

- ^ Turner (1978), p. 51.

- ^ Jackson (1978), p. 101.

- ^ Turner (1978), p. 37.

- ^ Turner (1978), pp. 253–71.

- ^ Turner (1978), pp. 61–65.

- ^ Turner (1978), p. 126.

- ^ Turner (1978), pp. 85–88.

- ^ Awdry 1990, p. 187.

- ^ Turner (1978), pp. 98–100.

- ^ Turner (1978), pp. 170–71.

- ^ Pratt (1921), pp. 1032–33.

- ^ a b Jordan (1998).

- ^ Marx (2007), p. 49.

- ^ Eborall and Smiles (1867).

- ^ Spence (1952), pp. 27–59.

- ^ White (1961), p. 44.

- ^ a b Turner (1977), pp. 112–13.

- ^ Turner (1978), p. 262

- ^ London Brighton & South Coast Railway (1867).

- ^ London Brighton & South Coast Railway (1867), Appendix C.

- ^ Heap and van Riemsdijk (1980), p. 89.

- ^ Turner (1979), pp. 3–14.

- ^ 'Railway amalgamation', (1875), pp. 430–31.

- ^ Lawson (1891), p. 91.

- ^ Lawson (1891) pp. 6, 91.

- ^ 'Return of Running of Passenger Trains on Main and Branch Lines of London, Brighton and S. Coast, London, Chatham and Dover, London and S.W. and S.E. Railways, April–June 1889,' House of Commons Papers, 1889.

- ^ Awdry (1990), pp. 189–90.

- ^ Turner (1979), p. 66.

- ^ Turner (1978), pp. 137–40, 244–45.

- ^ Robertson (1985).

- ^ Ahrons, E.L. (1953). Locomotive and train working in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Vol. 5. Cambridge: Heffer and Sons. pp. 87–8.

- ^ Turner (1979), pp. 64-67.

- ^ a b Acworth (1888), p. 97

- ^ Ellis (1971), p. 172. quoting J. Pearson Pattinson, The London, Brighton & South Coast Railway, its Passenger Services, Rolling Stock, Locomotives, Gradients and Express Speeds, (Cassell, 1896).

- ^ Dendy Marshall (1968), p. 237.

- ^ Turner (1979), p. 118.

- ^ Heap and van Riemsdijk (1980), p. 78.

- ^ Marx (2007), p. 9.

- ^ Pratt (1921), pp. 1032–41.

- ^ a b Pratt (1921), pp. 1038–39.

- ^ Marx (2007), 55.

- ^ Marx (2007), 46.

- ^ Marx (2007), 49–51.

- ^ Marx (2007), 55–6.

- ^ Marx (2007), Chapter 5.

- ^ Marx (2007), 75–77.

- ^ Ellis, (1960), 209.

- ^ Marshall (1963), p. 248.

- ^ Bonavia (1987), p.19.

- ^ Ahrons (1953), vol. 5, pp. 62–65.

- ^ Acworth (1888), p. 91.

- ^ Burtt and Beckerlegge (1948).

- ^ Ahrons (1953), vol. 5, p. 47.

- ^ Ellis (1979), pp. 98–99.

- ^ Rich (1996), 118.

- ^ Gray (1977), pp. 86–87.

- ^ Fryer (1997).

- ^ Kidner (1984), p. 3.

- ^ 'Return from Great Northern, Great Eastern, London and N.W., Great Western, Midland, S.E., London, Chatham and Dover, London, Brighton and S. Coast, and London and S.W. Railway Companies of Arrival at London Stations of Passenger Trains, as shown in Time-Tables, 1890', House of Commons. Papers Number: 151, 1890.

- ^ Turner (1977), p. 187.

- ^ 'The London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway Company Ran Its First Special Sunday Cycle Train to Horley, Three Bridges, and East Grinstead This Week'. Illustrated London News (London, England), Saturday, 11 May 1901; 698.

- ^ 'In the Tourist and Excursion Programme of the London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway Company Will Be Found Announced Cheap Week-end Tickets to Be Issued on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday to Tall Places on the South Coast from Hastings to Portsmouth Inclusive, and to All Places in the Isle of Wight, Also to Dieppe, the Parisian's Favourite Seaside Resort.' Illustrated London News (Saturday, 15 July 1905) 106.

- ^ Dendy Marshall (1968), p. 240.

- ^ Riley (1967), p. 8.

- ^ Bradley (1974), pp. 60–61.

- ^ Bradley (1974), pp. 62–68.

- ^ Ellis (1971), p. 199.

- ^ Marx (2008), p. 19.

- ^ a b Acworth (1888), p. 98

- ^ Marx (2008), pp. 21–22.

- ^ Marx (2008), pp. 98–99.

- ^ Turner, J.T. Howard (1978), p. 175.

- ^ Turner (1978), p. 22.

- ^ Turner (1978), pp. 121, 232.

- ^ Turner, J.T. Howard (1978) p. 241 and Turner (1979), p. 154.

- ^ Turner (1979), p. 76.

- ^ Moody (1968).

- ^ ISBN 978-1-906419-65-3

- ^ Sherrington (1928), vol. 2 p. 235.

- ^ Marshall, (1963), p. 1.

- ^ Moody, (1968) pp. 6–7.

- ^ Sherrington (1928), vol. 2, p. 236.

- ^ Dawson (1921).

- ^ Richards (1923), p. 32.

- ^ Moody, (1968), p. 25.

- ^ Turner (1978), pp. 16–18, 292–95.

- ^ Turner (1978), pp. 285–88.

- ^ "Accident Archive:Accident at Falmer on 6th June 1851". Railway Archive. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ "Accident Archive:Accident at Ford on 27th November 1851". Railway Archive. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ISBN 0-7153-8305-1.

- ^ "Death on the tracks: A 19th century train crash". OpenLearn. The Open University. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "Accident Archive: Accident at Croydon on 21st August 1854". Railway Archive. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ "Accident Archive: Accident at Falmer Incline on 3rd October 1859". Railway Archive. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ "Accident Archive: Accident at Clayton Tunnel on 25th August 1861". Railway Archive. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ "Accident Archive: Accident at Streatham on 29th May 1863". Railway Archive. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ "Accident Archive: Accident at New Cross on 23rd June 1869". Railway Archive. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ISBN 0-906899-03-6.

- ^ "Accident Archive: Accident at Norwood Junction on 1st May 1891". Railway Archive. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ "Accident at Farlington, 1894". The Why and Wherefore. Railway Magazine. Vol. 123, no. 919. November 1977. p. 571.

- ^ ISBN 0-906899-01-X.

- ^ "Accident Archive: Accident at Keymer Junction on 23rd December 1899". Railway Archive. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ISBN 0-906899-37-0.

- ^ Esbester, Mike (15 October 2018). "Burns Awareness – past & present". Railway Work, Life & Death. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ ISBN 0-906899-05-2.

- ^ a b Signal Boxes of the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway

- ^ Marshall (1978), p. 189.

- ^ Turner (1978), p. 99.

- ^ Gordon (1910), pp. 159–60.

- ^ Bradley (1974), pp. 64–65.

- ^ Bradley (1969), p. 173.

- ^ Baxter (1977), pp. 69–72.

- ^ Ellis (1979), p. 104.

- ^ Acworth (1888), p. 99.

- ^ Marx (2005), 46.

- ^ Bradley (1974), p. 126.

- ^ Riley (1967), p. 10.

- ^ Cooper (1990), p. 46.

- ^ a b Ellis (1979), p. 69.

- ^ Gray (1977), p. 123.

- ^ Acworth (1888), pp. 92–93.

- ^ Ellis (1979), p. 200.

- ^ Acworth (1888), p. 94).

- ^ Bonavia (1987), pp. 16–17.

- ^ Cooper (1990,) pp. 46–54.

- ^ Cooper (1990), pp. 55–64.

- ^ Acworth (1888), pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b Measom (1852), p. vi.

- ^ 25 & 26 Vict. c. lxviii 30 June 1862,

- ^ Acworth (1888), p. 101.

- ^ Acworth (1888), p. 105.

- ^ Hoard (1974), p. 22.

- ^ Green, Alan H. J. (July 2013). "The railway buildings of T. H. Myres". Newsletter of the Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society (159): 12.

- ^ Cooper (1981), p. 58.

- ^ Hawkins (1979).

- ^ 'Reconstruction of the Grosvenor Hotel' (1901).

- ^ Mitchell and Smith (1983), picture no. 5.

- ^ London Brighton and South Coast Railway Official Guide (1912), p. 262.

- ^ Ottley (1965) item 6741.

- ^ Ottley (1965) items 6742, 6745–6748.

- ^ Lawson (1891), p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bradshaw's Railway Manual, Shareholders' Guide and Official Directory for 1905. London: Henry Blacklock & Co. Ltd. p. 187.

- ^ 'Termination of the strike on the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway' (1867).

- ^ The London Brighton and South Coast Railway Co. 1846–1922 (1923), p. 14.

- ^ Marx (2005), 109–138.

Bibliography

- Acworth, W.M. "The London and Brighton Railway". Murray's Magazine 4 (19) (July 1888). London: John Murray.

- Ahrons, Ernest L. (1953). Locomotive & Train Working in the Latter Part of the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: Heffer. OCLC 11899921

- ISBN 1-85260-049-7.

- Baxter, Bertram; Baxter, David (1977). British Locomotive Catalogue, 1825–1923. Buxton: Moorland. ISBN 978-0-903485-50-0.

- Bonavia, Michael R. (1987). The History of the Southern Railway. London: Unwin Hyman. ISBN 0-04-385107-X.

- Bradley, Donald Laurence (1969). Locomotives of the London Brighton and South Coast Railway: Part 1. Railway Correspondence and Travel Society.

- Bradley, D.L. (1972). Locomotives of the London Brighton and South Coast Railway: Part 2. Railway Correspondence and Travel Society.

- Bradley, D.L. (1974). Locomotives of the London Brighton and South Coast Railway: Part 3. Railway Correspondence and Travel Society.

- Burtt, Frank (1975) The locomotives of the London Brighton and South Coast Railway 1839-190, 2nd edition, 3.Branch Line

- Burtt, Frank; Beckerlegge, W. (1948). Pullman and Perfection. London: Ian Allan. OCLC 316139331

- Cooper, B.K. (1981). Rail Centres: Brighton. Nottingham: Booklaw. ISBN 1-901945-11-1.

- Cooper, Peter (1990) LBSCR Stock Book. Cheltenham: Runpast. ISBN 1-870754-13-1.

- Dawson, Philip, (1921). Report by Sir Philip Dawson On Proposed Substitution of Electric for Steam Operation for Suburban, Local and Mainline Passenger and Freight Services. London Brighton and South Coast Railway.

- Dendy Marshall, Chapman Frederick; Kidner, Roger Wakely. A History of the Southern Railway. 2nd edition. London: Ian Allan 1963. Originally published 1936. OCLC 315039503

- Eborall, C.W.; Smiles, S. (1863). Report of the General Manager and Secretary On the Relations of the South Eastern and Brighton Companies. London: South Eastern Railway.

- Eddolls, John (1983). The Brighton line. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-8251-9.

- Ellis, C. Hamilton (1960). The London, Brighton and South Coast Railway: A Mechanical History of the London and Brighton, the London and Croydon, and the London, Brighton and South Coast Railways from 1839 to 1922. London: Ian Allan. OCLC 500637942

- Fryer, C.E.J. (1997). A History of Slipping and Slip Carriages. Usk: Oakwood Press. ISBN 978-0-85361-514-9

- Gordon, W.J. (1910) Our Home Railways. London: F.J. Warne.

- Gray, Adrian (1997). The London to Brighton Line 1841–1977. Blandford Forum: Oakwood Press. OCLC 4570078

- Hawkins, Chris; Reeve, George (1979). An Historical Survey of Southern Sheds. Oxford: Oxford Publishing. ISBN 0-86093-020-3.

- Haworth, R.B. Miramar Ship Index (Requires Login). Wellington, New Zealand.

- Heap, Christine; van Riemsdijk, John (1980). The Pre-Grouping Railways part 2. H.M.S.O. for the Science Museum. ISBN 0-11-290309-6.

- Hoare, John (1974). Railway Architecture in Sussex. Sussex Industrial History, Sussex Industrial History Society, 6.

- Jordan, S. (1998). Ferry Services of the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway. Usk: The Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-521-7.

- Jackson, Alan A. (1978). London's Local Railways. Newton Abbott, David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7479-6

- Kidner, R.W. (1984). Southern suburban steam 1860–1967. The Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-298-6.

- Lawson, W.R. (1891). The Brighton Railway: Its Resources and Prospects. London: "Financial Times" Office. OCLC 55652812

- London Brighton and South Coast Railway Official Guide. (1912), LB&SCR.

- The London Brighton and South Coast Railway Co. 1846–1922. (1923) London Brighton and South Coast Railway.

- London Brighton & South Coast Railway (1867). Report of the Committee of Investigation. LB&SCR.

- Dendy Marshall, C.F. (1968). History of the Southern Railway. ISBN 0-7110-0059-X.

- Marx, Klaus (2005). Douglas Earle Marsh: His Life and Times. Oakwood Press, ISBN 978-0-85361-633-7.

- Marx, Klaus (2007). Lawson Billinton: A Career Cut Short. Oakwood Press, ISBN 978-0-85361-661-0.

- Marx, Klaus (2008). Robert Billinton: An Engineer Under Pressure. Usk: The Oakwood Press, ISBN 978-0-85361-676-4.

- OCLC 55653470

- Mitchell, Vic and Smith, Keith (1983) South Coast Railways p- Brighton to Worthing. Middleton Press.

- Moody, George T. (1968). Southern Electric 1909–1968. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-0017-9.

- Ottley, George (1965). A Bibliography of British Railway History. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- Pratt, Edwin A. (1921). British railways and the Great War. London: Selwyn & Blount. OCLC 1850596

- "Railway amalgamation", (1875) Saturday Review. 3 April pp. 430–31.

- Rich, Frederick 'Yesterday once more: a story of Brighton stea', Bromley, P.E. Waters & Associates, 1996.

- Richards, Henry Walter Huntingford (1923). "Twelve years' operation of electric traction on the London Brighton and South Coast Railway", Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Session 1922–1923. London: Institution of Civil Engineers.

- "Reconstruction of the Grosvenor Hotel", (1901), British Architect. 4 January, p. 17.

- Riley, R.C. (1967). Brighton Line Album. London: Ian Allan. p. 8. ISBN 0711003939.

- Robertson, K. (1985). The Southsea Railway. Southampton: Kingfisher. ISBN 0-946184-16-X.

- Searle, Muriel V. (1986). Down the Line to Brighton. Baton Transport. OCLC 60079352

- Sekon, G.A. (1895). History of the South Eastern Railway. Economic Printing and Publishing Co.

- Sherrington, C.E.R. The Economics of Rail Transport in Great Britain. London, Edward Arnold & Co., 1928.

- Spence, Jeoffry (1952). The Caterham Railway: The Story of a Feud and Its Aftermath. Oakwood Press.

- Swiggum, S.; Kohli, M. The Ships List. London, Brighton & South Coast Railway Company.

- "Termination of the strike on the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway". Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle. 30 March 1867.

- Turner, John Howard (1977), The London Brighton and South Coast Railway 1 Origins and Formation. Batsford, ISBN 0-7134-0275-X

- Turner, John Howard (1978), The London Brighton and South Coast Railway 2 Establishment and Growth. Batsford, ISBN 0-7134-1198-8

- Turner, John Howard (1979), The London Brighton and South Coast Railway 3 Completion and Maturity. Batsford, ISBN 0-7134-1389-1.

- White, H.P. (1961). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: II. Southern England. Phoenix House.