London and North Western Railway

| |

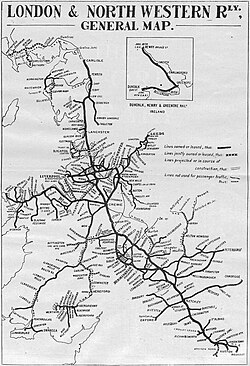

1920 map of the railway | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Euston railway station |

| Dates of operation | 16 July 1846–31 December 1922 |

| Predecessor | Grand Junction Railway London and Birmingham Railway Manchester and Birmingham Railway |

| Successor | London, Midland and Scottish Railway |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) |

| Length | 2,066 miles 6 chains (3,325.0 km) (1919)[1] |

| Track length | 5,818 miles 59 chains (9,364.4 km) (1919)[1] |

The London and North Western Railway (LNWR, L&NWR) was a British

Dubbed the "Premier Line", the LNWR's main line connected four of the largest cities in England; London, Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool, and, through cooperation with their Scottish partners, the Caledonian Railway also connected Scotland's largest cities of Glasgow and Edinburgh. Today this route is known as the West Coast Main Line. The LNWR's network also extended into Wales and Yorkshire.

In 1923, it became a constituent of the London, Midland and Scottish (LMS) railway, and, in 1948, the London Midland Region of British Railways.

History

| London and North Western Railway Act 1846 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

9 & 10 Vict. c. cciv |

The company was formed on 16 July 1846 by the amalgamation of the Grand Junction Railway, London and Birmingham Railway and the Manchester and Birmingham Railway. This move was prompted, in part, by the Great Western Railway's plans for a railway north from Oxford to Birmingham.[6] The company initially had a network of approximately 350 miles (560 km),[6] connecting London with Birmingham, Crewe, Chester, Liverpool and Manchester.

The headquarters were at Euston railway station. As traffic increased, it was greatly expanded with the opening in 1849 of the Great Hall, designed by Philip Charles Hardwick in classical style. It was 126 ft (38 m) long, 61 ft (19 m) wide and 64 ft (20 m) high and cost £150,000[7] (equivalent to £16,550,000 in 2021).[8] The station stood on Drummond Street.[9] Further expansion resulted in two additional platforms in the 1870s with four more in the 1890s, bringing the total to 15.[10]

The LNWR described itself as the Premier Line. This was justified, as it included the pioneering

With the Grand Junction Railway acquisition of the North Union Railway in 1846, the London and North Western Railway operated as far north as Preston.[11] In 1859, the Lancaster and Preston Junction Railway amalgamated with the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway and this combined enterprise was leased to the London and North Western Railway, giving it a direct route from London to Carlisle.[12]

In 1858, they merged with the Chester and Holyhead Railway and became responsible for the lucrative Irish Mail trains via the North Wales Main Line to Holyhead.[13]

On 1 February 1859, the company launched the limited mail service, which was only allowed to take three passenger coaches, one each for Glasgow, Edinburgh and Perth. The Postmaster General was always willing to allow a fourth coach, provided the increased weight did not cause time to be lost in running. The train was timed to leave Euston at 20.30 and operated until the institution of a dedicated post train, wholly of Post Office vehicles, in 1885.[14] On 1 October 1873 the first sleeping carriage ran between Euston and Glasgow, attached to the limited mail. It ran three nights a week in each direction. On 1 February 1874 a second carriage was provided and the service ran every night.[14]

In 1860, the company pioneered the use of the water trough designed by John Ramsbottom.[15][16] It was introduced on a section of level track at Mochdre, between Llandudno Junction and Colwyn Bay.[14]

The company inherited several manufacturing facilities from the companies with which it merged, but these were consolidated and in 1862, locomotive construction and maintenance was done at the

At the core of the LNWR system was the main line network connecting

The LNWR also had the

At its peak just before World War I, it ran a route mileage of more than 1,500 miles (2,400 km), and employed 111,000 people. In 1913, the company achieved a total revenue of £17,219,060 (equivalent to £1,802,570,000 in 2021)[8] with working expenses of £11,322,164[19] (equivalent to £1,185,260,000 in 2021).[8]

On 1 January 1922, one year before it amalgamated with other railways to create the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS), the LNWR amalgamated with the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (including its subsidiary the Dearne Valley Railway) and at the same time absorbed the North London Railway and the Shropshire Union Railways and Canal Company, both of which were previously controlled by the LNWR. With this, the LNWR achieved a route mileage (including joint lines, and lines leased or worked) of 2,707.88 miles (4,357.91 km).[20][21]

The company built a war memorial in the form of an obelisk outside Euston station to commemorate the 3,719 of its employees who died in the First World War. After the Second World War, the names of the LMS's casualties were added to the LNWR's memorial.[22]

The LNWR were also involved in the mass manufacture of replacement legs in the mid 19th century and the early 20th century. This is due-to the routine demand for prostheses for disabled staff. Serious injuries that resulted in the loss of limbs were common at this time with over 4,963 casualties in the year of 1910 on the LNWR alone, and over 25,000 injuries across the whole industry, manufacturing prostheses resulted in self-sufficiency for the company.[23][24][25][26]

Electrification

From 1909 to 1922, the LNWR undertook a large-scale project to

Successors

The LNWR became a constituent of the London, Midland and Scottish (LMS) railway when the railways of Great Britain were merged in the grouping of 1923. Ex-LNWR lines formed the core of the LMS's Western Division.

Acquisitions

- Anglesey Central Railway, 1876

- Ashby and Nuneaton Joint Railway (partnership with the Midland Railway) 1873

- Aylesbury Railway,[27]1846

- Bedford and Cambridge Railway, 1865

- Birkenhead Railway, 1861 (jointly with GWR)

- Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Stour Valley Railway, 1847 (the Stour Valley Line)

- Brynmawr and Blaenavon Railway, 1869

- Brynmawr and Western Valleys Railway, 1902 (jointly with GWR)

- Buckinghamshire Railway,[28] 1847

- Cannock Chase Railways, 1863

- Cannock Mineral Railway, 1869

- Carnarvon and Llanberis Railway, 1870

- Carnarvonshire Railway, 1870

- Central Wales Railway, 1868

- Central Wales and Carmarthen Junction Railway, 1891

- Central Wales Extension Railway, 1868

- Chester and Holyhead Railway, 1858

- Cockermouth and Workington Railway, 1866

- Conway and Llanrwst Railway, 1867

- Cromford and High Peak Railway, 1862

- Denbigh, Ruthin and Corwen Railway, 1879

- Dundalk, Newry and Greenore Railway, 1869

- Fleetwood, Preston and West Riding Junction Railway, 1867 (jointly with Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway)

- Hampstead Junction Railway, 1867

- Harrow and Stanmore Railway, 1899

- Huddersfield and Manchester Railway and Canal, 1847

- Knighton Railway, 1863

- Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway, 1921

- Lancashire Union Railway, 1883 (jointly with Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway)

- Lancaster and Carlisle Railway, 1859

- Leeds, Dewsbury and Manchester Railway, 1847

- Ludlow and Clee Hill Railway, 1892 (jointly with GWR)

- Manchester South Junction and Altrincham Railway, 1849 (jointly with Sheffield, Ashton-under-Lyne and Manchester Railway)

- Merthyr, Tredegar and Abergavenny Railway, 1862

- Nerquis Railway, 1866

- Newport Pagnell Railway, 1875

- North and South Western Junction Railway, 1871 (jointly with the Midland Railway and the North London Railway)

- North London Railway, 1909 (NLR retained own Board)

- Northampton and Peterborough Railway, 1846

- Oldham, Ashton and Guide Bridge Railway, 1862 (jointly with the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway)

- Portpatrick and Wigtownshire Railway, 1885 (jointly with Midland Railway, Caledonian Railway and Glasgow and South Western Railway)

- Preston and Wyre Railway, 1847 (jointly with Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway)

- Rugby and Leamington Railway, 1848

- Rugby and Stamford Railway, 1846

- St George's Harbour, 1861

- St Helens Canal and Railway, 1864

- Shrewsbury and Hereford Railway, 1862 (jointly with GWR and West Midland Railway)

- Shrewsbury and Welshpool Railway, 1864 (jointly with GWR from 1865)

- Shropshire Union Railways and Canal, 1847

- Sirhowy Railway, 1876

- South Leicestershire Railway, 1867

- South Staffordshire Railway, 1861

- Stockport, Disley and Whaley Bridge Railway, 1866

- Trent Valley Railway, 1847

- Tenbury Railway, 1866 (jointly with GWR from 1869)

- Vale of Clwyd Railway, 1867

- Vale of Towy Railway, 1884 (jointly with GWR from 1889)

- Warrington and Stockport Railway, 1859

- Watford and Rickmansworth Railway, 1881

- LBSCR)

- Whitehaven, Cleator and Egremont Railway, 1877 (jointly with Furness Railway from 1878)

- Whitehaven Junction Railway, 1866

Locomotives

The LNWR's main engineering works were at

Accidents and incidents

Major accidents on the LNWR include:

- On 26 March 1850, the boiler of a locomotive exploded at Wolverton, Buckinghamshire due to tampering of the safety valves. One person was injured.[29]

- On 30 April 1851 a train returning from Chester Races broke down in Sutton tunnel, and the following train ran into it. Six passengers were killed.[14]

- On 6 September 1851 a train run for the Great Exhibition returning from Euston to Oxford derailed at Bicester and six passengers were killed.[14]

- On 6 March 1853, the boiler of a locomotive exploded at Longsight, Lancashire. Six people were killed and the engine shed was severely damaged.[29]

- On 27 August 1860 a passenger train collided with a goods train at Craven Arms and one passenger was killed.[14]

- On 16 November 1860 the Irish night mail ran into a cattle train at Atherstone. The fireman of the mail train, and nine drovers in the cattle train were killed.[14]

- On 11 June 1861, a . Both engine crew were killed.

- On 2 September 1861 a ballast train came out of a siding onto the main line just past Kentish Town Junction without the signalman's permission, and an excursion train from Kew ran past the signals and collided with it, resulting in the deaths of fourteen passengers and two employees.[14]

- On 29 June 1867, a passenger train ran into the rear of a coal train at Warrington, Cheshire due to a pointsman's error which was compounded by the lack of interlocking between points and signals. Eight people were killed and 33 were injured.

- On 20 August 1868, a rake of wagons ran away from Llandulas, Denbighshire during shunting operations. The wagons subsequently collided with the Irish Mail at Abergele, Denbighshire. Kerosene being carried in the wagons set the wreck on fire. Thirty-three people were killed in what was then the deadliest rail accident to have occurred in the United Kingdom.

- On 14 September 1870, a mail train was diverted into a siding at Tamworth station, Staffordshire due to a signalman's error. The train crashed through the buffers and ended up in the River Anker, killing three people.[30]

- In 1870, a Carlisle, Cumberland. Five people were killed. The driver of the freight train was intoxicated.[30]

- On 26 November 1870, a mail train was in a rear-end collision with a freight train at

- On 2 August 1873, a passenger train derailed at Wigan, Lancashire due to excessive speed. Thirteen people were killed and 30 were injured.

- On 22 December 1894, a wagon was derailed fouling the main line at Chelford, Cheshire. It was run into by an express passenger train, which was derailed. Fourteen people were killed and 48 were injured.

- On 15 August 1895, an express passenger train was derailed at Preston, Lancashire due to excessive speed on a curve. One person was killed.[31]

- On 12 January 1899, An express freight train was derailed at Penmaenmawr, Caernarfonshire due to the trackbed being washed away by the sea during a storm. Both locomotive crew were killed.[32]

- On 15 August 1903, two passenger trains collided at Preston, Lancashire due to faulty points.[33]

- On 15 October 1907, a mail train was derailed at Shrewsbury, Shropshire due to excessive speed on a curve. Eighteen people were killed.[34]

- On 19 August 1909, a passenger train was derailed at Friezland, West Yorkshire. Two people were killed.[35]

- On 5 December 1910, a passenger train was in a rear-end collision at

- On 17 September 1912, the driver of an express train misread signals at Ditton Junction, Cheshire. The train was derailed when it ran over points at an excessive speed. Fifteen people were killed.

- On 14 August 1915, an express passenger train was derailed at Weedon, Northamptonshiredue to a locomotive defect. Ten people were killed and 21 were injured.

- On 11 November 1921, the boiler of a locomotive exploded at Buxton, Derbyshire. Two people were killed.[37]

Minor incidents include:

- In 1900, wagons of a permanent way train carrying sleepers were set on fire by the heat of the sun at Earlestown, Lancashire, destroying some of them.[34]

Ships

The LNWR operated ships on Irish Sea crossings between Holyhead and Dublin, Howth, Kingstown or Greenore. At Greenore, the LNWR built and operated the Dundalk, Newry and Greenore Railway to link the port with the Belfast–Dublin line operated by the Great Northern Railway.

The LNWR also operated a joint service with the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway from Fleetwood to Belfast and Derry.

Notable people

Chairmen of the Board of Directors

- 1846–1852 – George Glyn, later 1st Baron Wolverton

- 1852–1853 – Major-General George Anson

- 1853–1861 – 3rd Duke of Buckingham and Chandos

- 1861 – Admiral Constantine Richard Moorsom

- 1861–1891 – Richard Moon, Sir Richard Moon from 1887

- 1891–1911 – The Lord Stalbridge

- 1911–1921 – Gilbert Claughton, Sir Gilbert Claughton from 1912

- 1921–1923 – Baron Lawrence of Kingsgate

Members of the Board of Directors

- John Pares Bickersteth[38]

- Michael Linning Melville[39]

- Frederick Baynes[38]

- Henry Booth

- John Albert Bright[38]

- Ralph Brocklebank[38]

- Sir Thomas Brooke, 1st Baronet[38]

- Philip Henry Chambres[38]

- William E. Dorrington[38]

- Edmund Faber, 1st Baron Faber[38]

- Alfred Fletcher[38]

- Samuel Robert Graves[40]

- Rupert Guinness, 2nd Earl of Iveagh[38]

- Theodore Julius Hare[38]

- John Hick[41]

- The Hon. A. H. Holland-Hibbert[38]

- Sir William Houldsworth, 1st Baronet[38]

- J. Bruce Ismay[38]

- Lieut-Col. Amelius Lockwood, 1st Baron Lambourne[38]

- The Hon. William Lowther[38]

- Brigadier-General Lewis Vivian Loyd[38]

- Miles MacInnes[38]

- Edward Nettlefold[38]

- David Plunket, 1st Baron Rathmore[38]

- Cromartie Sutherland-Leveson-Gower, 4th Duke of Sutherland[38]

- Henry Ward[38]

General Managers

- 1846–1858 – Captain Mark Huish

- 1858–1874 – William Cawkwell

- 1874–1893 – Sir George Findlay(knighted 1892)

- 1893–1908 – Sir Frederick Harrison (knighted in 1902)

- 1909–1914 – Sir Frank Ree (knighted 1913)

- 1914 – Sir Robert Turnbull (knighted 1913)

- 1914–1919 – Sir Guy Calthrop (made a baronet 1918)

- 1919–1920 – Isaac Thomas Williams (knighted c.1919)

- 1920–1923 – Arthur Watson

Chief Civil Engineers

- Robert Stephenson until 1859

- William Baker 1859 – 1878[42]

- Francis Stevenson 1879 – 1902[43]

- Edward Baylies Thornhill 1902[44] – 1909

- Ernest Frederic Crosbie Trench 1909[45] – 1923 (afterwards chief engineer of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway)

Locomotive Superintendents and Chief Mechanical Engineers

Southern Division:

- 1846–1847 – Edward Bury

- 1847–1862 – James McConnell

North Eastern Division:

- 1846–1857 – John Ramsbottom[46]

NE Division became part of N Division in 1857.

Northern Division:

- 1846–1857 – Francis Trevithick

- 1857–1862 – John Ramsbottom[46]

Northern and Southern Divisions amalgamated from April 1862:

- 1862–1871 – John Ramsbottom[46]

- 1871–1903 – Francis William Webb

- 1903–1909 – George Whale

- 1909–1920 – Charles Bowen Cooke

- 1920–1921 – Hewitt Pearson Montague Beames

- 1922 – George Hughes (ex-Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway)

Solicitors

- 1830–1861 – Samuel Carter, with continuing role for subsidiary companies[47]

Preservation

- Sections of the former L&NWR are Northampton & Lamport Railway, the latter giving the name Premier Line to its quarterly journal.[48]

- A section of the former L&NWR line and station buildings are preserved at Quainton near Aylesbury. It is administered by the Buckinghamshire Railway preservation Society and houses some original L&NWR rolling stock in the former Oxford Rewley Road station. It regularly runs steam trains using various locomotives.

See also

- Great Northern and London and North Western Joint Railway

- Nickey Line

- Croxley Rail Link

- Rail transport in Great Britain

References

- ^ a b The Railway Year Book for 1920. London: The Railway Publishing Company Limited. 1920. p. 176.

- doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/45712. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- ISBN 9781846682131. "The LNWR was the largest joint-stock company of its time, with a capitalisation of over £29 million in 1851".

- ^ Sheppard, Richard; Roberts, David. "Basil Oliver Moon BA". Magdalen College, Oxford. The Slow Dusk. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ "London and North Western Railway Company". Institution of Mechanical Engineers. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-85045-060-6.

- ^ "Opening of the new Grand Station and Vestibule of the London and North-Western Railway". Chelmsford Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 25 May 1849. Retrieved 1 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ www.motco.com Archived 18 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine – 1862 map, showing position of 1849 station.

- ^ "Euston Station, London". Network Rail. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ "One Hundred Years of British Railways. No. XI. Part II – The first half century. The London and North Western Railway". The Engineer: 288–290. 12 September 1924.

- ^ "One Hundred Years of British Railways. No. XII. Part II – The first half century. The London and North Western Railway". The Engineer: 319–321. 19 September 1924.

- ^ "The Importance of Passenger Traffic". London and North Western Railway Society. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "One Hundred Years of British Railways. No. XIII. Part II – The first half century. The London and North Western Railway". The Engineer: 354–356. 26 September 1924.

- ^ Robbins, Michael (1967). Points and Signals. London: George Allen & Unwin.[page needed]

- ^ Acworth, J. M. (1889). The Railways of England. London: John Murray.[page needed]

- ^ Barrie, D. S. M. (1957). The Dundalk, Newry & Greenore Railway and the Holyhead – Greenore Steamship Service. Usk, UK: The Oakwood Press.

- ^ "Map of LNWR". London and North Western Railway Society. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "London and North-Western Railway". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. British Newspaper Archive. 21 February 1914. Retrieved 1 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ISBN 0-906899-66-4.

- ISBN 0-7153-4906-6.

- ^ Historic England. "War Memorial (1342044)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Esbester, Mike (15 December 2017). "Disability History Month – rehabilitating injured workers? The case of the one-legged engine driver". Railway Work, Life & Death. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ "Drawing of an artificial leg from Crewe". National Railway Museum blog. 24 July 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ "Disability History Month: Of accidents and prosthetics". National Railway Museum blog. 21 December 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ Esbester, Mike (10 December 2018). "Working after the accident". Railway Work, Life & Death. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ISBN 9780860934387.

- ^ Banbury To Verney Junction (Lnwr)[permanent dead link]. Disused-rlys.fotopic.net. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ^ ISBN 0-7153-8305-1.

- ^ ISBN 0-7110-1929-0.

- ISBN 0-906899-03-6.

- ISBN 0-906899-03-6.

- ISBN 0-906899-37-0.

- ^ ISBN 0-906899-01-X.

- ISBN 0-906899-05-2.

- ISBN 0-906899-50-8.

- ISBN 0-906899-52-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Bradshaw's Railway Manual, Shareholders' Guide and Official Directory for 1905. London: Henry Blacklock & Co. Ltd. pp. 201–202.

- ^ Railway Reminiscences by George P. Neele Late Superintendent of the Line of the London and North Western Railway, Morquorquodale & Co., London 1904, Chapter VII

- ^ Debretts House of Commons and the Judicial Bench 1870

- ISSN 1753-7843.

- ^ "Death of Mr. William Baker". Morning Post. England. 21 December 1878. Retrieved 20 February 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Death of a Railway Engineer". Nuneaton Observer. England. 14 February 1902. Retrieved 20 February 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "New Engineer to the London and North-Western Railway". Belfast News-Letter. Northern Ireland. 8 March 1902. Retrieved 20 February 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "London and North-Western Railway Staff Changes". Railway News. England. 9 October 1909. Retrieved 20 February 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7153-7489-4.

- ^ "Samuel Carter". Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Premier Line Archived 13 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Northampton and Lamport Railway (26 January 2008). Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- Reed, M. C. (1996). The London & North Western Railway. Penryn: Atlantic Transport. ISBN 978-0-906899-66-3

Further reading

- Measom, George (1859), Official Illustrated Guide to the North-Western Railway, London: W.H. Smith and Son

- Shaw, George (1876), The official tourists' picturesque guide to the London and North-western Railway : and other railways with which it is immediately in connection, embracing information respecting tours in England, Ireland, and Scotland : specially prepared for the use of American tourists, London, Boston: Norton and Shaw, Estes and Lauriat, OL 26199401M

- Steel, Wilfred L. (1914), The history of the London & North Western Railway, Railway and Travel Monthly

- Darroch, G. R. S. (1920), Deeds of a great railway; a record of the enterprise and achievements of the London and North-Western Railway Company during the Great War, John. Murray

- Head, Francis Bond (1849), Stokers and pokers; or, The London and North-Western Railway, the electric telegraph, and the Railway Clearing-House, John. Murray, 1861 edition

- Findlay, George (1889),(2nd ed.)

- Smith, Neil (March 2021), The London & North Western Railway, Articles from the Railway Magazine Archives, Pen & Sword, ISBN 978-1-5267-8137-6

External links

- "J. Hudson & Co Beaufort whistle, Railway, L&NWR, Kings Whistle, Made by J.Hudson & Co. One of their Best Made models.", Whistle Museum (image), archived from the original on 9 February 2013

- London and North Western Railway Society, Registered Charity L&NWR Society No. 1110210