Madison Grant

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2021) |

Madison Grant | |

|---|---|

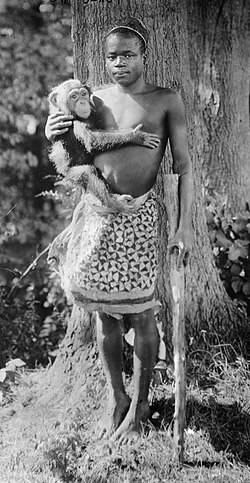

Grant in the early 1920s | |

| Born | November 19, 1865 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | May 30, 1937 (aged 71) New York City, U.S. |

| Resting place | Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Tarrytown, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Columbia University Yale University |

| Occupation(s) | Lawyer, writer, zoologist |

| Known for | Eugenics, Scientific racism, The Passing of the Great Race, Nordicism |

| Part of a series on |

| Eugenics in the United States |

|---|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Eugenics |

|---|

|

Madison Grant (November 19, 1865 – May 30, 1937) was an American lawyer, zoologist, anthropologist, and writer known for his work as a conservationist, eugenicist, and advocate of scientific racism. Grant is less noted for his far-reaching achievements in conservation than for his pseudoscientific advocacy of Nordicism, a form of racism which views the "Nordic race" as superior.[1][2]

As a white supremacist eugenicist, Grant was the author of The Passing of the Great Race (1916), one of the most famous racist texts, a book Adolf Hitler referred to as his personal Bible.[3] Grant also played an active role in crafting immigration restriction and anti-miscegenation laws in the United States.[4][5] As a conservationist, he is credited with the saving of species including the American bison,[6] helped create the Bronx Zoo, Glacier National Park, and Denali National Park, and co-founded the Save the Redwoods League.[7] Grant developed much of the discipline of wildlife management.[8]

Early life

Grant was born in New York City, the son of

Grant was the oldest of four siblings. The children's summers, and many of their weekends, were spent at Oatlands, the Long Island country estate built by their grandfather DeForest Manice in the 1830s.[12] As a child, he attended private schools and traveled Europe and the Middle East with his father. He attended Yale University, graduating early and with honors in 1887. He received a law degree from Columbia Law School, and practiced law after graduation; however, his interests were primarily those of a naturalist. He never married and had no children. He first achieved a political reputation when he and his brother, DeForest Grant, took part in the 1894 electoral campaign of New York mayor William Lafayette Strong.

Career and conservation efforts

Thomas C. Leonard wrote that "Grant was a cofounder of the American environmental movement, a crusading conservationist who preserved the California redwoods; saved the American bison from extinction; fought for stricter gun control laws; helped create Glacier and Denali national parks; and worked to preserve whales, bald eagles, and pronghorn antelopes."[13]

Grant was a friend of several U.S. presidents,[

He was also a developer of

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, he served on the boards of many

Grant's campaigns for conservationism and eugenics were not unrelated: both assumed the need for various types of stewardship over their charges.[19] Grant was generally indifferent to forms of animal life that he did not regard as aristocratic, and assigned such a hierarchy to humans as well.[1] Historian Jonathan Spiro wrote, "Whereas wildlife managers felt that the survival of the species as a whole was more important than the lives of a few individuals, so Grant preached that the fate of the race outweighed that of a few particular humans who were 'of no value to the community'."[19] In Grant's mind, natural resources needed to be conserved for the "Nordic race" to the exclusion of other races. Grant viewed the Nordic race as he did any of his endangered species, and considered the modern industrial society as infringing just as much on its existence as it did on the redwoods.[citation needed] Like many eugenicists, Grant saw modern civilization as a violation of "survival of the fittest", whether it manifested itself in the over-logging of the forests, or the survival of the poor via welfare or charity.[5][20] In the words of the New Yorker, for figures such as Grant, "it was an unsettlingly short step from managing forests to managing the human gene pool".[1]

Nordicism

Grant was the author of the once much-read book The Passing of the Great Race[21] (1916), an elaborate work of racial hygiene attempting to explain the racial history of Europe. The most significant of Grant's concerns was with the changing "stock" of American immigration of the early 20th century (characterized by increased numbers of immigrants from Southern Europe and Eastern Europe, as opposed to Western Europe and Northern Europe), Passing of the Great Race was a "racial" interpretation of contemporary anthropology and history, stating race as the basic motor of civilization.

Similar ideas were proposed by prehistorian Gustaf Kossinna in Germany. Grant promoted the idea of the "Nordic race",[20] a loosely defined biological-cultural grouping rooted in Scandinavia, as the key social group responsible for human development; thus the subtitle of the book was The racial basis of European history. As an avid eugenicist, Grant further advocated the separation, quarantine, and eventual collapse of "undesirable" traits and "worthless race types" from the human gene pool and the promotion, spread, and eventual restoration of desirable traits and "worthwhile race types" conducive to Nordic society.

He wrote, "A rigid system of selection through the elimination of those who are weak or unfit—in other words social failures—would solve the whole question in one hundred years, as well as enable us to get rid of the undesirables who crowd our jails, hospitals, and insane asylums. The individual himself can be nourished, educated and protected by the community during his lifetime, but the state through sterilization must see to it that his line stops with him, or else future generations will be cursed with an ever increasing load of misguided sentimentalism. This is a practical, merciful, and inevitable solution of the whole problem, and can be applied to an ever widening circle of social discards, beginning always with the criminal, the diseased, and the insane, and extending gradually to types which may be called weaklings rather than defectives, and perhaps ultimately to worthless race types."[22][excessive quote]

Grant's work is considered one of the most influential and vociferous works of scientific racism and eugenics to come out of the United States. Stephen Jay Gould described The Passing of the Great Race as "the most influential tract of American scientific racism".[23] The Passing of the Great Race was published in multiple printings in the United States, and was translated into other languages, including German in 1925. By 1937, the book had sold 16,000 copies in the United States alone.[24][25][26]

The book was embraced by proponents of the Nazi movement in Germany and was the first non-German book ordered to be reprinted by the Nazis when they took power. Adolf Hitler wrote to Grant, "The book is my Bible."[19][27]

One of Grant's long-time opponents was the anthropologist

Grant represented the "

Immigration restriction

Grant advocated restricted immigration to the United States through limiting immigration from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe, as well as the complete end of immigration from East Asia. He also advocated efforts to purify the American population through selective breeding. He served as the vice president of the

Though Grant was extremely influential in legislating his view of racial theory, he began to fall out of favor in the United States in the early 1930s. The declining interest in his work has been attributed both to the effects of the Great Depression, which resulted in a general backlash against Social Darwinism and related philosophies, and to the changing dynamics of racial issues in the United States during the interwar period. Rather than subdivide Europe into separate racial groups, the bi-racial (black vs. white) views of Grant's protegé Lothrop Stoddard became more dominant in the aftermath of the Great Migration of African-Americans from Southern States to Northern and Western ones (Guterl 2001).[citation needed]

Legacy

According to historian of economics Thomas C. Leonard: "Prominent American eugenicists, including movement leaders

Leonard wrote that Grant also opposed war, had doubts about imperialism, and supported birth control.[35]

Leonard's view that eugenicists such as Grant were conservatives is an outlier, however. Writer Jonah Goldberg has noted that "eugenics lay at the heart of the progressive enterprise" and was embraced by almost all early progressives, from Margaret Sanger to H.G. Wells and John Maynard Keynes.[36] Likewise, Thomas Sowell has noted that most leading eugenicists were firmly ensconced within progressive intellectual circles, where the desire for the government to take strong action to protect the gene pool went hand-in-hand with other statist views, including opposition to free-market capitalism.[37] Similarly, historian Edwin Black has stated that the eugenic crusade was "created in the publications and academic research rooms of the Carnegie Institution, verified by the research grants of the Rockefeller Foundation, validated by leading scholars from the best Ivy League universities, and financed by the special efforts of the Harriman railroad fortune."[38] From this perspective, it is perfectly understandable that Madison Grant—a graduate of elite Ivy League universities and a strong advocate for various progressive causes of the day—would also be a eugenicist.

Grant became a part of popular culture in 1920s America, especially in New York. Grant's conservationism and fascination with zoological natural history made him influential among the New York elite, who agreed with his cause, most notably

At the postwar

Grant's works of scientific racism have been cited to demonstrate that many of the genocidal and eugenic ideas associated with the Third Reich did not arise specifically in Germany, and in fact that many of them had origins in other countries, including the United States.[40] As such, because of Grant's well-connected and influential friends, he is often used to illustrate the strain of race-based eugenic thinking in the United States, which had some influence until the Second World War. Because of the use made of Grant's eugenics work by the policy-makers of Nazi Germany, his work as a conservationist has been somewhat ignored and obscured, as many organizations with which he was once associated (such as the Sierra Club) wanted to minimize their association with him.[19] His racial theories, which were popularized in the 1920s, are today seen as discredited.[41][42] The work of Franz Boas and his students, Ruth Benedict and Margaret Mead, demonstrated that there were no inferior or superior races.[42]

On June 15, 2021, California State Parks removed a memorial to Madison Grant from Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park placed in the park in 1948. The monument's removal is part of a broader effort in California Parks to address outdated exhibits and interpretations related to the founders of

Works

- The Caribou. New York: Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1902.

- "Moose". New York: Report of the Forest, Fish, Game Commission, 1903.

- The Origin and Relationship of the Large Mammals of North America. New York: Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1904.

- The Rocky Mountain Goat. Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1905.

- The Passing of the Great Race; or, The Racial Basis of European History. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1916.

- New ed., rev. and Amplified, with a New Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1918

- Rev. ed., with a Documentary Supplement, and a Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1921.

- Fourth rev. ed., with a Documentary Supplement, and a Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1936.

- Saving the Redwoods; an Account of the Movement During 1919 to Preserve the Redwoods of California. New York: Zoological Society, 1919.[45]

- Early History of Glacier National Park, Montana. Washington: Govt. print. off., 1919.

- The Conquest of a Continent; or, The Expansion of Races in America, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1933.

Selected articles

- "The Depletion of American Forests", Century Magazine, Vol. XLVIII, No. 1, May 1894.

- "The Vanishing Moose, and their Extermination in the Adirondacks", Century Magazine, Vol. XLVII, 1894.

- "A Canadian Moose Hunt". In: Theodore Roosevelt (ed.), Hunting in Many Lands. New York: Forest and Stream Publishing Company, 1895.

- "The Future of Our Fauna", Zoological Society Bulletin, No. 34, June 1909.

- "History of the Zoological Society", Zoological Society Bulletin, Decennial Number, No. 37, January 1910.

- "Condition of Wild Life in Alaska". In: Hunting at High Altitudes. New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1913.

- "Wild Life Protection", Zoological Society Bulletin, Vol. XIX, No. 1, January 1916.

- "The Passing of the Great Race", Geographical Review, Vol. 2, No. 5, Nov., 1916.

- "The Physical Basis of Race", Journal of the National Institute of Social Sciences, Vol. III, January 1917.

- "Discussion of Article on Democracy and Heredity", The Journal of Heredity, Vol. X, No. 4, April, 1919.

- "Restriction of Immigration: Racial Aspects", Journal of the National Institute of Social Sciences, Vol. VII, August 1921.

- "Racial Transformation of America", The North American Review, March 1924.

- "America for the Americans", The Forum, September 1925.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Purdy, Jedediah (2015). "Environmentalism's Racist History". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 2015-11-22. Retrieved 2022-08-15.

- U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the originalon 2022-06-07. Retrieved 2022-08-15.

- ^ Spiro 2009, p. 357.

- ^ ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the originalon 2019-11-07. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ a b "1890s-1930s: Eugenics, physical anthropology". NBC News. 2008-05-27. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ a b Spiro 2009, p. 67, 136.

- ^ Hoff, Aliya. "Madison Grant (1865–1937)". The Embryo Project Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2022-08-15.

- ^ Spiro 2009, p. 72.

- ^ Zubrin, Robert (2012). Merchants of Despair: Radical Environmentalists, Criminal Pseudo-scientists, and the Fatal Cult of Antihumanism. Encounter Books, p. 57.

- ^ Spiro 2009, p. 6–7.

- ^ "Maj. Gabriel Grant (Surgeon)". health.mil (the official website of the Military Health System and the Defense Health Agency). Archived from the original on June 27, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ Spiro 2009, p. 7.

- ^ Leonard, Thomas C. (2016). Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era. Princeton University Press. p. 116.

- ISBN 978-1-58465-810-8 – via Google Books.

- JSTOR 10.1086/659713.

- ^ "B&C Member Spotlight - Madison Grant". Boone and Crockett Club. 2021-12-09. Retrieved 2022-08-15.

- ^ "A New Kind of Zoo - B&C Impact Series". Boone and Crockett Club. 2022-02-14. Retrieved 2022-08-15.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-08-15.

- ^ a b c d e Spiro 2009.

- ^ JSTOR 274146.

- ^ Lindsay, J.A. (1917). "The Passing of the Great Race, or the Racial Basis of European History", The Eugenics Review 9 (2), pp. 139–141.

- ^ The Passing of the Great Race (1916), p. 46.

- ^ HARTMAN, NOEL (January 2016). ""THE PASSING OF THE GREAT RACE" AT 100". PublicBooks.org.

- ^ Hoff, Aliya R., "Madison Grant (1865-1937)" in Embryo Project Encyclopedia (online), (National Science Foundation, Arizona State University, June 20, 2021).

- ^ Okrent, Daniel (2019). The Guarded Gate: Bigotry, Eugenics, and the Law That Kept Two Generations of Jews, Italians, and Other European Immigrants Out of America. New York: Scribner. pp. 209–210.

- ^ Spiro 2009, pp. 143–166.

- ^ Whitney, Leon (1971). Autobiography of Leon Fradley Whitney. Islandora Repository. p. 205.

- ISBN 978-1-58046-348-5. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-8204-8146-3.

- ^ Spiro 2002

- ISBN 978-0-252-07463-9.

- JSTOR 2208521.

- S2CID 35570700.

- ^ Leonard, Thomas C. Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era. Princeton UP, 2016. p. 115.

- ^ Leonard, Thomas C. Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era. Princeton UP, 2016. p. 116.

- ^ Goldberg, Jonah. Liberal Fascism: The Secret History of the American Left, from Mussolini to the Politics of Change. Broadway Books, 2007. p. 248.

- ^ Sowell, Thomas. Social Justice Fallacies. Basic Books, 2023. p. 36.

- ^ Black, Edwin. War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America's Campaign to Create a Master Race. Dialog Press, 2003. p. xviii.

- ^ Spiro 2009, p. xiii.

- ^ Black, Edwin (2003). War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America's Campaign to Create a Master Race. New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, pp. 259, 273, 274–275, 296.

- ISBN 978-0-691-00437-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-13-555714-3.

- ^ Vanderheiden, Isabella (June 28, 2021). "Memorial removed from Prairie Creek over racist, eugenics beliefs of Save the Redwoods League founder". Times-Standard. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "California State Parks Removes Memorial to Madison Grant from Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park". CA State Parks (Press release). June 25, 2021. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- ^ Reprinted in The National Geographic, Vol. XXXVII, January/June, 1920.

Further reading

- Allen, Garland E. (2013). "'Culling the Herd': Eugenics and the Conservation Movement in the United States, 1900-1940". Journal of the History of Biology 46, pp. 31–72.

- Barkan, Elazar (1992). The Retreat of Scientific Racism: Changing Concepts of Race in Britain and the United States between the World Wars. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Cooke, Kathy J. (2000). "Grant, Madison". American National Biography. Oxford University Press. Online.

- Degler, Carl N. (1991). In Search of Human Nature: The Decline and Revival of Darwinism in American Social Thought. Oxford University Press.

- Field, Geoffrey G. (1977). "Nordic Racism", Journal of the History of Ideas 38 (3), pp. 523–540.

- Guterl, Matthew Press (2001). The Color of Race in America, 1900–1940. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lee, Erika. "America first, immigrants last: American xenophobia then and now." Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 19.1 (2020): 3-18.

- Leonard, Thomas C. Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era (Princeton UP, 2016).

- Leonard, Thomas C. "'More Merciful and Not Less Effective': Eugenics and American Economics in the Progressive Era". History of Political Economy 35.4 (2003): 687-712.

- Marcus, Alan P. "The Dangers of the Geographical Imagination in the US Eugenics Movement". Geographical Review 111.1 (2021): 36-56.

- Purdy, Jedediah (2015). "Environmentalism's Racist History". The New Yorker.

- Serwer, Adam (April 2019). "White Nationalism's Deep American Roots". The Atlantic.

- Spiro, Jonathan P. Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant (Univ. of Vermont Press, 2009) Excerpt.

- Spiro, Jonathan P. "Nordic vs. Anti-Nordic: The Galton Society and the American Anthropological Association", Patterns of Prejudice 36#1 (2002): 35–48.

- Regal, Brian (2002). Henry Fairfield Osborn: Race and the Search for the Origins of Man. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

- Regal, Brian (2004). "Maxwell Perkins and Madison Grant: Eugenics Publishing at Scribners", Princeton University Library Chronicle 65#2, pp. 317–341.

External links

- Madison Grant at Find a Grave

- Excerpts from Passing of the Great Race used at the Nuremberg Trials

- Works by Madison Grant at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Madison Grant at Project Gutenberg