Sabaic

| Sabaic | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Yemen |

| Region | Arabian Peninsula |

| Extinct | 6th century |

| Ancient South Arabian | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | xsa |

xsa | |

| Glottolog | saba1279 |

Sabaic, sometimes referred to as Sabaean, was an

Script

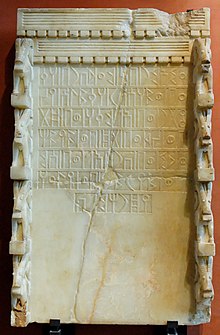

Sabaic was written in the

The South Arabic alphabet used in

Sabaic is attested in some 1,040 dedicatory inscriptions, 850 building inscriptions, 200 legal texts, and 1300 short graffiti (containing only personal names).[9] No literary texts of any length have yet been brought to light. This paucity of source material and the limited forms of the inscriptions has made it difficult to get a complete picture of Sabaic grammar. Thousands of inscriptions written in a cursive script (called Zabur) incised into wooden sticks have been found and date to the Middle Sabaic period; these represent letters and legal documents and as such includes a much wider variety of grammatical forms.

Varieties

- Sabaic: the language of the kingdom of very well documented, c. 6000 inscriptions

- Old Sabaic: mostly Ma'rib and the Highlands.[11]

- Middle Sabaic: 3rd century BC until the end of the 3rd century AD. The best-documented language.AwwamTemple (otherwise known as Maḥrem Bilqīs) in Ma'rib.

- Amiritic/Ḥaramitic: the language of the area to the north of Ma'īn[12]

- Central Sabaic: the language of the inscriptions from the Sabaean heartland

- South Sabaic: the language of the inscriptions from Ḥimyar

- "Pseudo-Sabaic": the literary language of Arabian tribes in Najrān, Ḥaram and Qaryat al-Fāw

- Late Sabaic: 4th–6th centuries AD.[11] This is the monotheistic period when Christianity and Judaism brought Aramaic and Greek influences.

- Old Sabaic: mostly

In the Late Sabaic period the ancient names of the gods are no longer mentioned and only one deity

The dialect used in the western Yemeni highlands, known as Central Sabaic, is very homogeneous and generally used as the language of the inscriptions. Divergent dialects are usually found in the area surrounding the Central Highlands, such as the important dialect of the city of

Phonology

Vowels

Since Sabaic is written in an

Diphthongs

In the Old Sabaic inscriptions the Proto-Semitic

Consonants

Sabaic, like

The exact nature of the emphatic consonants q, ṣ, ṭ, ẓ and ḍ also remains a matter for debate: were they pharyngealized as in Modern Arabic, or were they glottalized as in

Sabaic consonants

| Bilabial | Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | voiceless | t

|

k | q? | ʔ ⟨ʾ⟩ | |||||

| voiced | b | d

|

ɡ | |||||||

| emphatic | tˀ ⟨ṭ⟩ | kʼ ⟨ḳ⟩? | ||||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | θ ⟨ṯ⟩ | s ⟨s3 /s⟩ | ʃ ⟨s1 /š⟩ | x ⟨ḫ⟩ | ħ ⟨ḥ⟩ | h | ||

| voiced | ð ⟨ḏ⟩ | z | ɣ ⟨ġ⟩ | ʕ ⟨ˀ⟩ | ||||||

| emphatic | θˀ ⟨ẓ⟩? | sˀ ⟨ṣ⟩? | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n

|

||||||||

| Lateral | voiceless | ɬ ⟨s2 /ś⟩

|

||||||||

| voiced | l

|

|||||||||

| emphatic | ɬˀ ⟨ḍ⟩? | |||||||||

| Rhotic | r

|

|||||||||

| Semivowel | w | j ⟨y⟩ | ||||||||

Grammar

Personal pronouns

As in other Semitic languages Sabaic had both independent pronouns and pronominal suffixes. The attested pronouns, along with suffixes from Qatabanian and Hadramautic are as follows:

| Pronominal suffixes | Independent pronouns | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sabaic | Other languages | Sabaic | ||

Singular

|

First person | -n | ʾn | |

| Second person m. | -k | -k | ʾnt; ʾt | |

| Second person f. | -k | |||

| Third person m.

|

-hw, h | -s1w(w), s1 | h(w)ʾ | |

| 3rd Person f.

|

-h, hw | -s1, -s1yw (Qataban.), -ṯ(yw), -s3(yw) (Hadram.) | hʾ | |

| Dual | 2nd Person | -kmy | ʾtmy | |

| 3rd Person com. | -hmy | -s1mn (min.), -s1my (Qataban.; Hadram.) | hmy | |

| 3rd Person m. | -s1m(y)n (Hadram.) | |||

| Plural | 1st Person | -n | ||

| 2nd Person m. | -kmw | ʾntmw | ||

| 2nd Person f. | ||||

| 3. Person m.

|

-hm(w) | -s1m | hmw | |

| 3. Person f.

|

-hn | -s1n | hn | |

No independent pronouns have been identified in any of the other South Arabian languages. First- and second-person independent pronouns are rarely attested in the monumental inscription, but possibly for cultural reasons; the likelihood was that these texts were neither composed nor written by the one who commissioned them: hence they use third-person pronouns to refer to the one who is paying for the building and dedication or whatever. The use of the pronouns in Sabaic corresponds to that in other Semitic languages. The pronominal suffixes are added to verbs and prepositions to denote the object; thus: qtl-hmw "he killed them"; ḫmr-hmy t'lb "Ta'lab poured for them both"; when the suffixes are added to nouns they indicate possession: 'bd-hw "his slave").The independent pronouns serve as the subject of nominal and verbal sentences: mr' 't "you are the Lord" (a nominal sentence); hmw f-ḥmdw "they thanked" (a verbal sentence).

Nouns

Case, number and gender

Old South Arabian nouns fall into two genders: masculine and feminine. The feminine is usually indicated in the singular by the ending –t : bʿl "husband" (m.), bʿlt "wife" (f.), hgr "city" (m.), fnwt "canal" (f.). Sabaic nouns have forms for singular, dual and plural. The singular is formed without changing the stem, the plural can however be formed in a number of ways even in the very same word:

- Inner ("Broken") Plurals: as in Classical Arabic they are frequent.

- ʾ-Prefix: ʾbyt "houses" from byt "house"

- t-Suffix: especially frequent in words having the m-prefix: mḥfdt "towers" from mḥfd "tower".

- Combinations: for example ʾ–prefix and t-suffix: ʾḫrft "years" from ḫrf "year", ʾbytt "houses" from byt "house".

- without any external grammatical sign: fnw "canals" from fnwt (f.) "canal".

- w-/y-Infix: ḫrwf / ḫryf / ḫryft "years" from ḫrf "year".

- Reduplicational plurals are rarely attested in Sabaic: ʾlʾlt "gods" fromʾl "god".

- External ("Sound") plurals: in the masculine the ending differs according to the grammatical state (see below); in the feminine the ending is -(h)t, which probably represents *-āt ; this plural is rare and seems to be restricted to a few nouns.

The dual is already beginning to disappear in Old Sabaic; its endings vary according to the grammatical state: ḫrf-n "two years" (indeterminate state) from ḫrf "year".

Sabaic almost certainly had a case system formed by vocalic endings, but since vowels were involved they are not recognizable in the writings; nevertheless a few traces have been retained in the written texts, above all in the construct state.[17]

Grammatical states

As in other Semitic languages Sabaic has a few grammatical states, which are indicated by various different endings according to the gender and the number. At the same time external plurals and duals have their own endings for grammatical state, while inner plurals are treated like singulars. Apart from the construct state known in other Semitic languages, there is also an indeterminate state and a determinate state, the functions of which are explained below. The following are the detailed state endings:

| Constr. state | Indet. state | Det. state | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Singular | -∅ | -m | -n |

| Dual | -∅ / -y | -n | -nhn | |

| External plural | -w / -y | -n | -nhn | |

| Feminine | Singular | -t | -tm | -tn |

| Dual | -ty | -tn | -tnhn | |

| External plural | -t | -tm | -tn | |

The three grammatical states have distinct syntactical and semantic functions:

- The Status indeterminatus: marks an indefinite, unspecified thing : ṣlm-m "any statue".

- The Status determinatus: marks a specific noun: ṣlm-n "the statue".

- The Status constructus: is introduced if the noun is bound to a genitive, a personal suffix or — contrary to other Semitic languages — with a relative sentence:

- With a pronominal suffix: ʿbd-hw "his slave".

- With a genitive noun: (Ḥaḑramite) gnʾhy myfʾt "both walls of Maifa'at", mlky s1bʾ "both kings of Saba"

- With a relative sentence: kl 1 s1bʾt 2 w-ḍbyʾ 3 w-tqdmt 4 s1bʾy5 w-ḍbʾ6 tqdmn7 mrʾy-hmw8 "all1 expeditions2, battles3 and raids4, their two lords 8 conducted5, struck6 and led7" (the nouns in the construct state are italicized here).

Verbs

Conjugation

As in other West Semitic languages Sabaic distinguishes between two types of finite verb forms: the perfect which is conjugated with suffixes and the imperfect which is conjugated with both prefixes and suffixes. In the imperfect two forms can be distinguished: a short form and a form constructed using the n (long form esp. the n-imperfect), which in any case is missing in Qatabānian and Ḥaḍramite. In actual use it is hard to distinguish the two imperfect forms from each other.[18] The conjugation of the perfect and imperfect may be summarized as follows (the active and the passive are not distinguished in their consonantal written form; the verbal example is fʿl "to do"):

| Perfect | Imperfect | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short form | Long form | |||

| Singular | 1. P. | fʿl-k (?) | ||

| 2. P. m. | fʿl-k | |||

| 2. P. f. | fʿl-k | t-fʿl | t-fʿl-n | |

| 3. P. m. | fʿl | y-fʿl | y-fʿl-n | |

| 3. P. f. | fʿl-t | t-fʿl | t-fʿl-n | |

| Dual | 3. P. m. | fʿl(-y) | y-fʿl-y | y-fʿl-nn |

| 3. P. f. | fʿl-ty | t-fʿl-y | t-fʿl-nn | |

| Plural | 2. P. m. | fʿl-kmw | t-fʿl-nn | |

| 3. P. m. | fʿl-w | y-fʿl-w | y-fʿl-nn | |

| 3. P. f. | fʿl-y, fʿl-n (?) | t-fʿl-n(?) | t-fʿl-nn(?) | |

Perfect

The perfect is mainly used to describe something that took place in the past, only before conditional phrases and in relative phrases with a conditional connotation does it describe an action in the present, as in Classical Arabic. For example: w-s3ḫly Hlkʾmr w-ḥmʿṯt "And Hlkʾmr and ḥmʿṯt have pleaded guilty (dual)".

Imperfect

The imperfect usually expresses that something has occurred at the same time as an event previously mentioned, or it may simply express the present or future. Four

- Hathor" (Minaean).

- Precative is formed with l- and expresses wishes: w-l-y-ḫmrn-hw ʾlmqhw "may Almaqahu grant him".

- Jussive is also formed with l- and stands for an indirect order: l-yʾt "so should it come".

- Vetitive is formed with the negative ʾl". It serves to express negative wishes: w-ʾl y-hwfd ʿlbm "and no ʿilb-trees may be planted here“.

Imperative

The imperative is found in texts written in the zabūr script on wooden sticks, and has the form fˁl(-n). For example: w-'nt f-s3ḫln ("and you (sg.) look after").

Derived stems

By changing the consonantal roots of verbs they can produce various derivational forms, which change their meaning. In Sabaic (and other Old South Arabian languages) six such stems are attested. Examples:

- qny "to receive" > hqny "to sacrifice; to donate"

- qwm "to decree" > hqm "to decree", tqwmw "to bear witness"

Syntax

Position of clauses

The arrangement of clauses is not consistent in Sabaic. The first clause in an inscription always has the order (particle - ) subject – predicate (SV), the other main clauses of an inscription are introduced by w- "and" and always have – like subordinate clauses – the order predicate – subject (VS). At the same time the Predicate may be introduced by f.[19]

Examples:

| s1ʿdʾl w-rʾbʾl | s3lʾ | w-sqny | ʿṯtr | kl | ġwṯ |

| S1ʿdʾl and Rʾbʾl | they have offered up (3rd person plural perfect) | and have consecrated (3rd person plural perfect) | Athtar

|

complete | repair |

| Subject | Predicate | Indirect object | Direct object | ||

| "S1ʿdʾl and Rʾbʾl have offered up and consecrated all the repairs to Athtar ".

| |||||

| w-ʾws1ʾl | f-ḥmd | mqm | ʾlmqh |

| and Awsil | and he thanked (3rd-person sg. perfect) | Does (stat. constr.) | Almaqah |

| "and" – subject | "and" – predicate | Object | |

| "And Awsil thanked the power of Almaqah" | |||

Subordinate clauses

Sabaic is equipped with a number of means to form subordinate clauses using various conjunctions:

| Main clause | Subordinate clause | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w-y-s1mʿ-w | k-nblw | hmw | ʾgrn | b-ʿbr | ʾḥzb ḥbs2t | |

| "and" – 3rd p. pl. imperfect | Conjunction – 3rd p. pl. perfect | Attribute | Subject | Preposition | Prepositional object | |

| And they heard | that they sent | these | Najranites | to | Abyssinian tribes | |

| And they heard, that these Najranites had sent a delegation to the Abyssinian tribes. | ||||||

| Subordinate clause | Subordinate clause | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w-hmy | hfnk | f-tʿlmn | b-hmy | ||

| "And" – conjunction | 2. person sg. perfect | "Then" – imperative | Pronominal phrase | ||

| And if | you sent | and sign | on it | ||

| And if you send (it), sign it. | |||||

Relative clauses

In Sabaic, relative clauses are marked by a

| mn-mw | ḏ- | -y-s2ʾm-n | ʿbdm | f-ʾw | ʾmtm |

| "who" – enclitic | Relativiser | 3rd-person singular n-imperfect | Object | "and/ or" | Object |

| who | he buys | a male slave | or | a female slave | |

| Whoever buys a male or female slave [...] | |||||

| Main clause | Relative clause | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ḏn | mḥfdn yḥḏr | ḏm | b-s2hd | gnʾ | hgr-sm |

| Demonstrative pronoun | Subject | Relativiser | Preposition | Prepositional object | Possessor |

| this | the tower yḥḏr | which | opposite | wall | her city |

| this tower yḥḏr, which stands opposite the walls of her city (is located). | |||||

| ʾl-n | ḏ- | -l- | -hw | smyn w-ʾrḍn |

| God – Nunation | Relativiser | Preposition | Object (resumptive) | Subject |

| the God | which | for | him | heaven and earth |

| God, for Whom the heavens and the earth are = God, to Whom the heaven and the earth belong | ||||

Vocabulary

Although the Sabaic vocabulary is found in relatively diverse types of inscriptions (an example being that the south Semitic tribes derive their word wtb meaning "to sit" from the northwest tribe's word yashab/wtb meaning "to jump"),

See also

- Old South Arabian

- South Arabian Alphabet

- Himyaritic language

- Undeciphered -k language of ancient Yemen

- Ge'ez

- Kingdom of Aksum

- Sabaeans

- Himyarite Kingdom

- Sheba

- Eduard Glaser

- Carl Rathjens

- Joseph Halévy

- Walter W. Müller

References

- ISBN 0-19-922237-1.

- ^ Kogan & Korotayev 1997.

- ^ ISBN 9780511486890.

- ^ The Athenaeum. J. Lection. 1894. p. 88.

- ISBN 978-0-19-068766-3.

- ^ Kogan & Korotayev 1997, p. 221.

- ^ Weninger, Stefan. "Ge'ez" in Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha, p.732.

- ^ Stuart, Munro-Hay (1991). Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity page 57. Edinburgh: University Press.

- ^ a b N. Nebes, P. Stein: Ancient South Arabian, in: Roger D. Woodard (Hrsg.): The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2004

- ^ A. Avanzini: Le iscrizioni sudarabiche d'Etiopia: un esempio di culture e lingue a contatto. In: Oriens antiquus, 26 (1987), Seite 201–221

- ^ a b c d Avanzini, A (April–June 2006). "A Fresh Look at Sabaic". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 126 (2): 253–260. Retrieved 2013-09-20.

- ^ Stein, Peter (2007). "Materialien zur sabäischen Dialektologie: Das Problem des amiritischen ("haramitischen") Dialektes" [Materials on Sabaean Dialectology: The Problem of the Amirite ("Haramite") Dialect]. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft (in German). 157: 13–47.

- ^ Rebecca Hasselbach, Old South Arabian in Languages from the World of the Bible, edited by Holger Gzella

- ^ Norbert Nebes and Peter Stein, op. cit

- ^ Rebecca Hasselbach, in Languages from the World of the Bible (ed. by Holger Gzella), pg. 170

- ^ a b Kogan & Korotayev (1997), p. 223

- ^ Hierzu: P. Stein: Gibt es Kasus im Sabäischen?, in: N. Nebes (Hrg.): Neue Beiträge zur Semitistik. Erstes Arbeitstreffen der Arbeitsgemeinschaft Semitistik in der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft vom 11. bis 13. September 2000, S. 201–222

- ^ Details see: Norbert Nebes: Verwendung und Funktion der Präfixkonjugation im Sabäischen, in: Norbert Nebes (Hrsg.): Arabia Felix. Beiträge zur Sprache und Kultur des vorislamischen Arabien. Festschrift Walter W. Müller zum 60. Geburtstag. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, Pp. 191–211

- ^ Norbert Nebes: Die Konstruktionen mit /FA-/ im Altsüdarabischen. (Veröffentlichungen der Orientalischen Kommission der Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur Mainz, Nr. 40) Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1995

- ^ Mendenhall, George (2006). "Arabic in Semitic Linguistic History". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 126 (1): 17–25.

- ^ The usual modern Arabic word for "church" is kanīsah, from the same origin.

Bibliography

- A. F. L. Beeston: Sabaic Grammar, Manchester 1984 ISBN 0-9507885-2-X.

Kogan, Leonid; Korotayev, Andrey (1997). "Sayhadic Languages (Epigraphic South Arabian)". Semitic Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 157–183.

- N. Nebes, P. Stein: "Ancient South Arabian", in: Roger D. Woodard (Hrsg.): The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2004) ISBN 0-521-56256-2S. 454–487 (up to date) grammatical sketch with Bibliography).

- Maria Höfner: Altsüdarabische Grammatik (Porta linguarum Orientalium, Band 24) Leipzig, 1943

- A.F.L. Beeston, M.A. Ghul, W.W. Müller, J. Ryckmans: Sabaic Dictionary / Dictionnaire sabéen /al-Muʿdscham as-Sabaʾī (Englisch-Französisch-Arabisch) Louvain-la-Neuve, 1982 ISBN 2-8017-0194-7

- Joan Copeland Biella: Dictionary of Old South Arabic. Sabaean dialect Eisenbrauns, 1982 ISBN 1-57506-919-9

- Jacques Ryckmans, Walter W. Müller, Yusuf M. Abdallah: Textes du Yémen antique. Inscrits sur bois (Publications de l'Institut Orientaliste de Louvain 43). Institut Orientaliste, Louvain 1994. ISBN 2-87723-104-6

- Peter Stein: Die altsüdarabischen Minuskelinschriften auf Holzstäbchen aus der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek in München 1: Die Inschriften der mittel- und spätsabäischen Periode (Epigraphische Forschungen auf der Arabischen Halbinsel 5). Tübingen u.a. 2010. ISBN 978-3-8030-2200-4

- Sabaic Online Dictionary