Skin

| Skin | |

|---|---|

Elephant skin | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cutis |

| MeSH | D012867 |

| TA98 | A16.0.00.002 |

| TA2 | 7041 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Skin is the layer of usually soft, flexible outer tissue covering the body of a vertebrate animal, with three main functions: protection, regulation, and sensation.

Other

All mammals have some hair on their skin, even marine mammals like whales, dolphins, and porpoises that appear to be hairless. The skin interfaces with the environment and is the first line of defense from external factors. For example, the skin plays a key role in protecting the body against pathogens[3] and excessive water loss.[4] Its other functions are insulation, temperature regulation, sensation, and the production of vitamin D folates. Severely damaged skin may heal by forming scar tissue. This is sometimes discoloured and depigmented. The thickness of skin also varies from location to location on an organism. In humans, for example, the skin located under the eyes and around the eyelids is the thinnest skin on the body at 0.5 mm thick and is one of the first areas to show signs of aging such as "crows feet" and wrinkles. The skin on the palms and the soles of the feet is the thickest skin on the body at 4 mm thick. The speed and quality of wound healing in skin is promoted by estrogen.[5][6][7]

Fur is dense hair.[8] Primarily, fur augments the insulation the skin provides but can also serve as a secondary sexual characteristic or as camouflage. On some animals, the skin is very hard and thick and can be processed to create leather. Reptiles and most fish have hard protective scales on their skin for protection, and birds have hard feathers, all made of tough beta-keratins. Amphibian skin is not a strong barrier, especially regarding the passage of chemicals via skin, and is often subject to osmosis and diffusive forces. For example, a frog sitting in an anesthetic solution would be sedated quickly as the chemical diffuses through its skin. Amphibian skin plays key roles in everyday survival and their ability to exploit a wide range of habitats and ecological conditions.[9]

On 11 January 2024, biologists reported the discovery of the oldest known skin, fossilized about 289 million years ago, and possibly the skin from an ancient reptile.[10][11]

Etymology

The word skin originally only referred to dressed and tanned animal hide and the usual word for human skin was hide. Skin is a borrowing from

Structure in mammals

| Dermis | |

|---|---|

The distribution of the blood vessels in the skin of the sole of the foot. (Corium – TA alternate term for dermis – is labeled at upper right.) | |

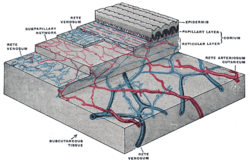

A diagrammatic sectional view of the skin (click on image to magnify). (Dermis labeled at center right.) | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D012867 |

| TA98 | A16.0.00.002 |

| TA2 | 7041 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Mammalian skin is composed of two primary layers:

- The epidermis, which provides waterproofing and serves as a barrier to infection.

- The appendagesof skin.

Epidermis

The epidermis is composed of the outermost layers of the skin. It forms a protective barrier over the body's surface, responsible for keeping water in the body and preventing

- Stratum corneum

- Stratum lucidum (only in palms and soles)

- Stratum granulosum

- Stratum spinosum

- Stratum basale (also called the stratum germinativum)

The

Basement membrane

The

Dermis

The dermis is the layer of skin beneath the

It harbors many

Dermis and subcutaneous tissues are thought to contain germinative cells involved in formation of horns, osteoderm, and other extra-skeletal apparatus in mammals.[2]

The

Papillary region

The papillary region is composed of loose

Reticular region

The reticular region lies deep in the papillary region and is usually much thicker. It is composed of dense irregular

Subcutaneous tissue

The

Detailed cross section

Structure in fish, amphibians, birds, and reptiles

Fish

This section relies largely or entirely upon a single source. (August 2021) |

The epidermis of

Although

Amphibians

Overview

Amphibians possess two types of

Granular glands

Granular glands can be identified as venomous and often differ in the type of toxin as well as the concentrations of secretions across various orders and species within the amphibians. They are located in clusters differing in concentration depending on amphibian taxa. The toxins can be fatal to most vertebrates or have no effect against others. These glands are alveolar meaning they structurally have little sacs in which venom is produced and held before it is secreted upon defensive behaviors.[25]

Structurally, the ducts of the granular gland initially maintain a cylindrical shape. When the ducts mature and fill with fluid, the base of the ducts become swollen due to the pressure from the inside. This causes the epidermal layer to form a pit like opening on the surface of the duct in which the inner fluid will be secreted in an upwards fashion.[26]

The intercalary region of granular glands is more developed and mature in comparison with mucous glands. This region resides as a ring of cells surrounding the basal portion of the duct which are argued to have an ectodermal muscular nature due to their influence over the lumen (space inside the tube) of the duct with dilation and constriction functions during secretions. The cells are found radially around the duct and provide a distinct attachment site for muscle fibers around the gland's body.[26]

The gland alveolus is a sac that is divided into three specific regions/layers. The outer layer or tunica fibrosa is composed of densely packed connective-tissue which connects with fibers from the spongy intermediate layer where elastic fibers, as well as nerves, reside. The nerves send signals to the muscles as well as the epithelial layers. Lastly, the epithelium or tunica propria encloses the gland.[26]

Mucous glands

Mucous glands are non-venomous and offer a different functionality for amphibians than granular. Mucous glands cover the entire surface area of the amphibian body and specialize in keeping the body lubricated. There are many other functions of the mucous glands such as controlling the pH, thermoregulation, adhesive properties to the environment, anti-predator behaviors (slimy to the grasp), chemical communication, even anti-bacterial/viral properties for protection against pathogens.[25]

The ducts of the mucous gland appear as cylindrical vertical tubes that break through the epidermal layer to the surface of the skin. The cells lining the inside of the ducts are oriented with their longitudinal axis forming 90-degree angles surrounding the duct in a helical fashion.[26]

Intercalary cells react identically to those of granular glands but on a smaller scale. Among the amphibians, there are taxa which contain a modified intercalary region (depending on the function of the glands), yet the majority share the same structure.[26]

The alveolar or mucous glands are much more simple and only consist of an epithelium layer as well as connective tissue which forms a cover over the gland. This gland lacks a tunica propria and appears to have delicate and intricate fibers which pass over the gland's muscle and epithelial layers.[26]

Birds and reptiles

This section relies largely or entirely upon a

Reptile scales The stratum germinativum and stratum corneum, but the other intermediate layers found in humans are not always distinguishable.

Hair is a distinctive feature of mammalian skin, while feathers are (at least among living species) similarly unique to birds.[24]

Birds and reptiles have relatively few skin glands, although there may be a few structures for specific purposes, such as pheromone-secreting cells in some reptiles, or the uropygial gland of most birds.[24] Development

Cutaneous structures arise from the paracrine signaling from FGF7 (keratinocyte growth factor) produced by the dermis below the basal cells. In mice, over-expression of these factors leads to an overproduction of granular cells and thick skin.[27][28]

Hair and feathers are formed in a regular pattern and it is believed to be the result of a reaction-diffusion system. This It is believed that the mesoderm defines the pattern. The epidermis instructs the mesodermal cells to condense and then the mesoderm instructs the epidermis of what structure to make through a series of reciprocal inductions. Transplantation experiments involving frog and newt epidermis indicated that the mesodermal signals are conserved between species but the epidermal response is species-specific meaning that the mesoderm instructs the epidermis of its position and the epidermis uses this information to make a specific structure.[29] FunctionsSkin performs the following functions:

MechanicsSkin is a soft tissue and exhibits key mechanical behaviors of these tissues. The most pronounced feature is the J-curve stress strain response, in which a region of large strain and minimal stress exists and corresponds to the microstructural straightening and reorientation of collagen fibrils.[33] In some cases the intact skin is prestreched, like wetsuits around the diver's body, and in other cases the intact skin is under compression. Small circular holes punched on the skin may widen or close into ellipses, or shrink and remain circular, depending on preexisting stresses.[34] AgingTissue fat cells which provide support. Common changes in the skin as a result of aging range from wrinkles, discoloration, and skin laxity, but can manifest in more severe forms such as skin malignancies.[35][36] Moreover, these factors may be worsened by sun exposure in a process known as photoaging.[36]

See also

References

External links

|