Neural crest

| Neural crest | |

|---|---|

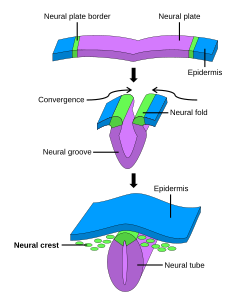

The formation of neural crest during the process of neurulation. Neural crest is first induced in the region of the neural plate border. After neural tube closure, neural crest delaminates from the region between the dorsal neural tube and overlying ectoderm and migrates out towards the periphery. | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D009432 |

| TE | crest_by_E5.0.2.1.0.0.2 E5.0.2.1.0.0.2 |

| FMA | 86666 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Neural crest cells are a temporary group of cells that arise from the embryonic

After

Underlying the development of neural crest is a

Therefore, defining the mechanisms of neural crest development may reveal key insights into vertebrate evolution and neurocristopathies.

History

Neural crest was first described in the chick embryo by Wilhelm His Sr. in 1868 as "the cord in between" (Zwischenstrang) because of its origin between the neural plate and non-neural ectoderm.[1] He named the tissue ganglionic crest since its final destination was each lateral side of the neural tube where it differentiated into spinal ganglia.[6] During the first half of the 20th century, the majority of research on neural crest was done using amphibian embryos which was reviewed by Hörstadius (1950) in a well known monograph.[7]

Cell labeling techniques advanced the field of neural crest because they allowed researchers to visualize the migration of the tissue throughout the developing embryos. In the 1960s, Weston and Chibon utilized radioisotopic labeling of the nucleus with tritiated thymidine in chick and amphibian embryo respectively. However, this method suffers from drawbacks of stability, since every time the labeled cell divides the signal is diluted. Modern cell labeling techniques such as rhodamine-lysinated dextran and the vital dye diI have also been developed to transiently mark neural crest lineages.[6]

The quail-chick marking system, devised by Nicole Le Douarin in 1969, was another instrumental technique used to track neural crest cells.[8][9] Chimeras, generated through transplantation, enabled researchers to distinguish neural crest cells of one species from the surrounding tissue of another species. With this technique, generations of scientists were able to reliably mark and study the ontogeny of neural crest cells.

Induction

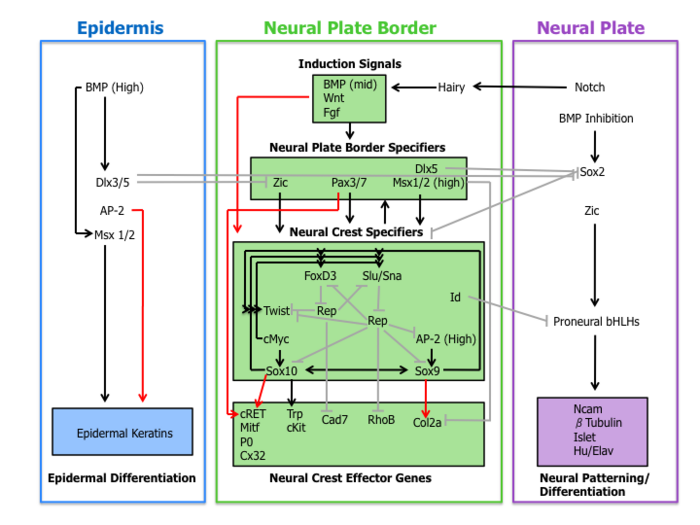

A molecular cascade of events is involved in establishing the migratory and multipotent characteristics of neural crest cells. This gene regulatory network can be subdivided into the following four sub-networks described below.

Inductive signals

First, extracellular signaling molecules, secreted from the adjacent

Wnt signaling has been demonstrated in neural crest induction in several species through gain-of-function and loss-of-function experiments. In coherence with this observation, the promoter region of slug (a neural crest specific gene) contains a binding site for transcription factors involved in the activation of Wnt-dependent target genes, suggestive of a direct role of Wnt signaling in neural crest specification.[10]

The current role of BMP in neural crest formation is associated with the induction of the neural plate. BMP antagonists diffusing from the ectoderm generates a gradient of BMP activity. In this manner, the neural crest lineage forms from intermediate levels of BMP signaling required for the development of the neural plate (low BMP) and epidermis (high BMP).[1]

Fgf from the paraxial mesoderm has been suggested as a source of neural crest inductive signal. Researchers have demonstrated that the expression of dominate-negative Fgf receptor in ectoderm explants blocks neural crest induction when recombined with paraxial mesoderm.[11] The understanding of the role of BMP, Wnt, and Fgf pathways on neural crest specifier expression remains incomplete.

Neural plate border specifiers

Signaling events that establish the neural plate border lead to the expression of a set of transcription factors delineated here as neural plate border specifiers. These molecules include Zic factors, Pax3/7, Dlx5, Msx1/2 which may mediate the influence of Wnts, BMPs, and Fgfs. These genes are expressed broadly at the neural plate border region and precede the expression of bona fide neural crest markers.[4]

Experimental evidence places these transcription factors upstream of neural crest specifiers. For example, in

Neural crest specifiers

Following the expression of neural plate border specifiers is a collection of genes including Slug/Snail, FoxD3, Sox10, Sox9, AP-2 and c-Myc. This suite of genes, designated here as neural crest specifiers, are activated in emergent neural crest cells. At least in Xenopus, every neural crest specifier is necessary and/or sufficient for the expression of all other specifiers, demonstrating the existence of extensive cross-regulation.[4] Moreover, this model organism was instrumental in the elucidation of the role of the Hedgehog signaling pathway in the specification of the neural crest, with the transcription factor Gli2 playing a key role.[14]

Outside of the tightly regulated network of neural crest specifiers are two other transcription factors Twist and Id. Twist, a

Neural crest effector genes

Finally, neural crest specifiers turn on the expression of effector genes, which confer certain properties such as migration and multipotency. Two neural crest effectors,

Migration

The migration of neural crest cells involves a highly coordinated cascade of events that begins with closure of the dorsal neural tube.

Delamination

After fusion of the neural fold to create the neural tube, cells originally located in the neural plate border become neural crest cells.[17] For migration to begin, neural crest cells must undergo a process called delamination that involves a full or partial epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).[18] Delamination is defined as the separation of tissue into different populations, in this case neural crest cells separating from the surrounding tissue.[19] Conversely, EMT is a series of events coordinating a change from an epithelial to mesenchymal phenotype.[18] For example, delamination in chick embryos is triggered by a BMP/Wnt cascade that induces the expression of EMT promoting transcription factors such as SNAI2 and FoxD3.[19] Although all neural crest cells undergo EMT, the timing of delamination occurs at different stages in different organisms: in Xenopus laevis embryos there is a massive delamination that occurs when the neural plate is not entirely fused, whereas delamination in the chick embryo occurs during fusion of the neural fold.[19]

Prior to delamination, presumptive neural crest cells are initially anchored to neighboring cells by

Migration

Neural crest cell migration occurs in a rostral to caudal direction without the need of a neuronal scaffold such as along a radial glial cell. For this reason the crest cell migration process is termed "free migration". Instead of scaffolding on progenitor cells, neural crest migration is the result of repulsive guidance via EphB/EphrinB and semaphorin/neuropilin signaling, interactions with the extracellular matrix, and contact inhibition with one another.[17] While Ephrin and Eph proteins have the capacity to undergo bi-directional signaling, neural crest cell repulsion employs predominantly forward signaling to initiate a response within the receptor bearing neural crest cell.[23] Burgeoning neural crest cells express EphB, a receptor tyrosine kinase, which binds the EphrinB transmembrane ligand expressed in the caudal half of each somite. When these two domains interact it causes receptor tyrosine phosphorylation, activation of rhoGTPases, and eventual cytoskeletal rearrangements within the crest cells inducing them to repel. This phenomenon allows neural crest cells to funnel through the rostral portion of each somite.[17]

Semaphorin-neuropilin repulsive signaling works synergistically with EphB signaling to guide neural crest cells down the rostral half of somites in mice. In chick embryos, semaphorin acts in the cephalic region to guide neural crest cells through the

Clinical significance

Waardenburg's syndrome

Waardenburg's syndrome is a neurocristopathy that results from defective neural crest cell migration. The condition's main characteristics include piebaldism and congenital deafness. In the case of piebaldism, the colorless skin areas are caused by a total absence of neural crest-derived pigment-producing melanocytes.[27] There are four different types of Waardenburg's syndrome, each with distinct genetic and physiological features. Types I and II are distinguished based on whether or not family members of the affected individual have dystopia canthorum.[28] Type III gives rise to upper limb abnormalities. Lastly, type IV is also known as Waardenburg-Shah syndrome, and afflicted individuals display both Waardenburg's syndrome and Hirschsprung's disease.[29] Types I and III are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion,[27] while II and IV exhibit an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. Overall, Waardenburg's syndrome is rare, with an incidence of ~ 2/100,000 people in the United States. All races and sexes are equally affected.[27] There is no current cure or treatment for Waardenburg's syndrome.

Hirschsprung's Disease

Also implicated in defects related to neural crest cell development and

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

DiGeorge syndrome

Treacher Collins Syndrome

Cell lineages

Neural crest cells originating from different positions along the

Cranial neural crest

Cranial neural crest migrates dorsolaterally to form the craniofacial mesenchyme that differentiates into various cranial ganglia and craniofacial cartilages and bones.

Trunk neural crest

Trunk neural crest gives rise two populations of cells.

Vagal and sacral neural crest

The vagal and sacral neural crest cells develop into the ganglia of the enteric nervous system and the parasympathetic ganglia.[35]

Cardiac neural crest

Evolution

Several structures that distinguish the vertebrates from other chordates are formed from the derivatives of neural crest cells. In their "New head" theory, Gans and Northcut argue that the presence of neural crest was the basis for vertebrate specific features, such as sensory ganglia and cranial skeleton. Furthermore, the appearance of these features was pivotal in vertebrate evolution because it enabled a predatory lifestyle.[38][39]

However, considering the neural crest a vertebrate innovation does not mean that it arose

Neural crest derivatives

Ectomesenchyme (also known as mesectoderm):

Endocrine cells: chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla, glomus cells type I/II.

Peripheral nervous system:

Satellite glial cells of all autonomic and sensory ganglia, Schwann cells of all peripheral nerves.Enteric cells:

Melanocytes, iris muscle and pigment cells, and even associated with some tumors (such as melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy).

See also

- First arch syndrome

- DGCR2—may control neural crest cell migration

- List of human cell types derived from the germ layers

References

- ^ PMID 15464568.

- PMID 20614636. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ Brooker, R.J. 2014, Biology, 3rd edn, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY, 1084

- ^ PMID 15363405.

- ^ PMID 17765683.

- ^ PMID 15296974.

- ^ Hörstadius, S. (1950). The Neural Crest: Its Properties and Derivatives in the Light of Experimental Research. Oxford University Press, London, 111 p.

- PMID 4191116.

- PMID 4121410.

- PMID 11402039.

- PMID 9281332.

- PMID 14627721.

- PMID 11684651.

- PMID 30086335.

- PMID 18539270.

- PMID 15772131.

- ^ ISBN 978-0123745392.

- ^ PMID 24556840.

- ^ PMID 22261150.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-139011-8.

- ^ a b Taneyhill, L.A. (2008). "To adhere or not to adhere: the role of Cadherins in neural crest development". Cell Adh Migr. 2, 223–30.

- PMID 23674598.

- ^ S2CID 10746234.

- PMID 29802835.

- ISSN 0046-8177.

- S2CID 210151171.

- ^ S2CID 23858201.

- PMID 5006208.

- ^ "Waardenburg syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. October 2012.

- S2CID 12394126.

- PMID 9451756.

- PMID 25219761.

- PMID 11005797.

- PMID 27895973.

- ^ a b c d Gilbert, Scott F. (2000). The Neural Crest. Sinauer Associates.

- PMID 28287247.

- S2CID 32986727.

- S2CID 39290007.

- PMID 16003768.

- PMID 16793256.

- PMID 18478530.

- PMID 23135395.

- ^ Kalcheim, C. and Le Douarin, N. M. (1998). The Neural Crest (2nd ed.). Cambridge, U. K.: Cambridge University Press.

- PMID 19786578.

- PMID 12645929.

- PMID 23639815.