Soil gas

Soil gases (soil atmosphere

Gases fill

Composition

| Gas | Soil | Atmosphere |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen | 79.2% | 78.0% |

| Oxygen | 20.6% | 20.9% |

| Carbon Dioxide | 0.25% | 0.04% |

The composition of

Processes

Gas molecules in soil are in continuous thermal motion according to the

The soil atmosphere's variable composition and constant motion can be attributed to chemical processes such as diffusion,

According to the

In regions of the world where freezing of soils or drought is common, soil thawing and rewetting due to seasonal or meteorological changes influences soil gas flux.[3] Both processes hydrate the soil and increase nutrient availability leading to an increase in microbial activity.[3] This results in greater soil respiration and influences the composition of soil gases.[7][3]

Studies and Research

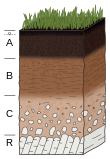

Soil gases have been used for multiple scientific studies to explore topics such as microseepage,[6] earthquakes,[8] and gaseous exchange between the soil and the atmosphere.[9][3] Microseepage refers to the limited release of hydrocarbons on the soil surface and can be used to look for petroleum deposits based on the assumption that hydrocarbons vertically migrate to the soil surface in small quantities.[6] Migration of soil gases, specifically radon, can also be examined as earthquake precursors.[8] Furthermore, for processes such as soil thawing and rewetting, for example, large sudden changes in soil respiration can cause increased flux of soil gases such as carbon dioxide and methane, which are greenhouse gases.[3] These fluxes and interactions between soil gases and atmospheric air can further be analyzed by distance from the soil surface.[9]

References

- ^ "Soil air" (PDF). Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ Pierzynski, Gary M.; Sims, J. Thomas; Vance, George F., eds. (2005). Soils and environmental quality (3rd ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ . Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- PMID 22195653. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ S2CID 83540675. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-803350-0. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ S2CID 40310421. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ PMID 12440516.

- ^ S2CID 49669782. Retrieved 6 November 2022.