Soil carbon

Soil carbon is the solid

Overview

| Part of a series on the |

| Carbon cycle |

|---|

|

Soil carbon is present in two forms: inorganic and organic. Soil inorganic carbon consists of mineral forms of carbon, either from

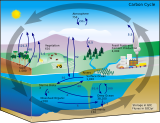

Global carbon cycle

Soil carbon distribution and accumulation arises from complex and dynamic processes influenced by biotic, abiotic, and anthropogenic factors.[5] Although exact quantities are difficult to measure, soil carbon has been lost through land use changes, deforestation, and agricultural practices.[6] While many environmental factors affect the total stored carbon in terrestrial ecosystems, in general, primary production and decomposition are the main drivers in balancing the total amount of stored carbon on land.[7] Atmospheric CO2 is taken up by photosynthetic organisms and stored as organic matter in terrestrial ecosystems.[8]

Although exact quantities are difficult to measure, human activities have caused substantial losses of soil organic carbon.[9] Of the 2,700 Gt of carbon stored in soils worldwide, 1550 GtC is organic and 950 GtC is inorganic carbon, which is approximately three times greater than the current atmospheric carbon and 240 times higher compared with the current annual fossil fuel emission.[10] The balance of soil carbon is held in peat and wetlands (150 GtC), and in plant litter at the soil surface (50 GtC). This compares to 780 GtC in the atmosphere, and 600 GtC in all living organisms. The oceanic pool of carbon accounts for 38,200 GtC.

About 60 GtC/yr accumulates in the soil. This 60 GtC/yr is the balance of 120 GtC/yr

Impacts of Climate Change on Soil

Climate change is a leading factor in

In contrast, tropical environments experience worsening soil quality because soil aggregation levels decrease with higher temperatures.Soil also has carbon sequestration abilities where carbon dioxide is fixed in the soil by plant uptakes.[16] This accounts for the majority of the Soil Organic Matter (SOM) in the ground, and creates a large storage pool (around 1500 Pg) for carbon in just the first few meters of soil and 20-40% of that organic carbon has a residence life exceeding 100 years.

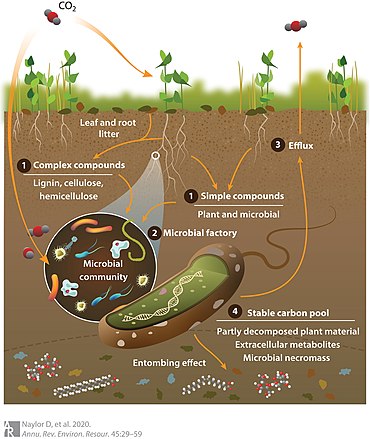

Organic carbon

Detritus resulting from plant senescence is the major source of soil organic carbon. Plant materials, with cell walls high in cellulose and lignin, are decomposed and the not-respired carbon is retained as humus. Cellulose and starches readily degrade, resulting in short residence times. More persistent forms of organic C include lignin, humus, organic matter encapsulated in soil aggregates, and charcoal. These resist alteration and have long residence times.

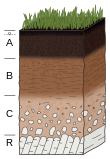

Soil organic carbon tends to be concentrated in the topsoil.

.Fire derived forms of carbon are present in most soils as unweathered charcoal and weathered black carbon.[19][20] Soil organic carbon is typically 5–50% derived from char,[21] with levels above 50% encountered in mollisol, chernozem, and terra preta soils.[22]

Root exudates are another source of soil carbon.[23] 5–20% of the total plant carbon fixed during photosynthesis is supplied as root exudates in support of rhizospheric mutualistic biota.[24][25] Microbial populations are typically higher in the rhizosphere than in adjacent bulk soil.

SOC and other soil properties

Soil organic carbon (SOC) concentrations in sandy soils influence soil bulk density which decreases with an increase in SOC.[26] Bulk density is important for calculating SOC stocks [27] and higher SOC concentrations increase SOC stocks but the effect will be somewhat reduced by the decrease in bulk density. Soil organic carbon increased the cation exchange capacity (CEC), a measure of soil fertility, in sandy soils. SOC was higher in sandy soils with higher pH. [28] found that up to 76% of the variation in CEC was caused by SOC, and up to 95% of variation in CEC was attributed to SOC and pH. Soil organic matter and specific surface area has been shown to account for 97% of variation in CEC whereas clay content accounts for 58%.[29] Soil organic carbon increased with an increase in silt and clay content. The silt and clay size fractions have the ability to protect SOC in soil aggregates.[30] When organic matter decomposes, the organic matter binds with silt and clay forming aggregates.[31] Soil organic carbon is higher in silt and clay sized fractions than in sand sized fractions, and is generally highest in the clay sized fractions.[32]

Soil health

Organic carbon is vital to soil capacity to provide

Losses

The exchange of carbon between soils and the atmosphere is a significant part of the world carbon cycle.

Although exact quantities are difficult to measure, human activities have caused massive losses of soil organic carbon. management that exposes soil (through either excessive or insufficient recovery periods) can also cause losses of soil organic carbon.

Managing soil carbon

Natural variations in soil carbon occur as a result of climate, organisms, parent material, time, and relief.[34] The greatest contemporary influence has been that of humans; for example, carbon in Australian agricultural soils may historically have been twice the present range that is typically 1.6–4.6%.[35]

It has long been encouraged that farmers adjust practices to maintain or increase the organic component in the soil. On one hand, practices that hasten oxidation of carbon (such as burning crop stubbles or over-cultivation) are discouraged; on the other hand, incorporation of organic material (such as in manuring) has been encouraged. Increasing soil carbon is not a straightforward matter; it is made complex by the relative activity of soil biota, which can consume and release carbon and are made more active by the addition of nitrogen fertilizers.[34]

Data available on soil organic carbon

Europe

The most homogeneous and comprehensive data on the organic carbon/matter content of European soils remain those that can be extracted and/or derived from the European Soil Database in combination with associated databases on land cover, climate, and topography. The modelled data refer to carbon content (%) in the surface horizon of soils in Europe. In an inventory on available national datasets, seven member states of the European Union have available datasets on organic carbon. In the article "Estimating soil organic carbon in Europe based on data collected through a European network" (Ecological Indicators 24,[36] pp. 439–450), a comparison of national data with modelled data is performed. The LUCAS soil organic carbon data are measured surveyed points and the aggregated results[37] at regional level show important findings. Finally, a new proposed model for estimation of soil organic carbon in agricultural soils has estimated current top SOC stock of 17.63 Gt[38] in EU agricultural soils. This modelling framework has been updated by integrating the soil erosion component to estimate the lateral carbon fluxes.[39]

Managing for catchment health

| Part of a series on |

| Biogeochemical cycles |

|---|

|

Much of the contemporary literature on soil carbon relates to its role, or potential, as an atmospheric carbon sink to offset climate change. Despite this emphasis, a much wider range of soil and catchment health aspects are improved as soil carbon is increased. These benefits are difficult to quantify, due to the complexity of natural resource systems and the interpretation of what constitutes soil health; nonetheless, several benefits are proposed in the following points:

- Reduced erosion, sedimentation: increased soil aggregate stability means greater resistance to erosion; mass movement is less likely when soils are able to retain structural strength under greater moisture levels.

- Greater productivity: healthier and more productive soils can contribute to positive socio-economic circumstances.

- Cleaner waterways, nutrients and turbidity: nutrients and sediment tend to be retained by the soil rather than leach or wash off, and are so kept from waterways.

- Water balance: greater soil water holding capacity reduces overland flow and recharge to groundwater; the water saved and held by the soil remains available for use by plants.

- Climate change: Soils have the ability to retain carbon that may otherwise exist as atmospheric CO2 and contribute to global warming.

- Greater biodiversity: soil organic matter contributes to the health of soil flora and, accordingly, the natural links with biodiversity in the greater biosphere.

Forest soils

The government of

West Africa has experienced significant loss of forest that contains high levels of soil organic carbon.[46][47] This is mostly due to expansion of small scale, non-mechanized agriculture using burning as a form of land clearance [48]

See also

- Biochar

- Biosequestration

- Carbon cycle

- Carbon farming

- Carbon sequestration

- Coarse woody debris

- Mycorrhizal fungi and soil carbon storage

- Soil regeneration and climate change

References

- S2CID 59574069. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ISSN 1752-0908.

- ISSN 0016-7061.

- ISSN 1543-592X.

- ISSN 1543-592X.

- ISSN 1752-0908.

- ISBN 978-0-12-814608-8.

- PMID 11030643.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-691-14634-8.

- .

- doi:10.1039/b809492f. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ "An Introduction to the Global Carbon Cycle" (PDF). University of New Hampshire. 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ a b Kimble, J.M.; Lal, R.; Grossman, R.B. "Alteration of Soil Properties Caused by Climate Change". Advances in GeoEcology. 31: 175–184.

- ^ Kimble, J.M.; Lal, R.; Grossman, R.B. "Alteration of Soil Properties Caused by Climate Change". Advances in GeoEcology. 31: 175–184.

- ^ Turner, J., & Overland, J. (2009). Contrasting climate change in the two polar regions. Polar Research, 28(2), 146–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-8369.2009.00128.x

- PMID 11607735.

- PMID 33873756.

- OSTI 1706683..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - ISBN 978-0-415-70415-1.

- .

- S2CID 54976103.

- PMID 22834642.

- ISBN 978-94-010-6218-3.

- .

- PMID 16676524.

- ISSN 0008-4271.

- ISSN 0008-4271.

- ISSN 0167-8809.

- ISSN 0361-5995.

- ISSN 0167-8809.

- ISSN 0167-8809.

- ISSN 0167-8809.

- Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-551550-3.

- ISBN 978-0-19-551762-0.

- .

- PMID 23178783.

- S2CID 10826877.

- PMID 30443596.

- ^ IPCC. 2000. Land use, land-use change, and forestry. IPCC Special Report. United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ IPCC. 2003. Good practice guidance for land use, land-use change and forestry. Kanagawa, Japan, National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme.

- ^ IPCC. 2006. Guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories. Kanagawa, Japan, National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme.

- S2CID 42458151.

- ^ "Forest monitoring and assessment".

- ^ FAO. 2012. "Soil carbon monitoring using surveys and modelling: General description and application in the United Republic of Tanzania". FAO Forestry Paper 168 Rome. Available at: http://www.fao.org/docrep/015/i2793e/i2793e00.htm

- S2CID 228861150.

- PMID 20868522.

- S2CID 247160560.