Special Activities Center: Difference between revisions

clarity - describe synonyms SOG and PAG at first description |

m →Syria |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 285: | Line 285: | ||

In December 2018, US President [[Donald Trump]] announced that US troops involved in the fight against the [[Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant|Islamic State]] (ISIS) in northeast Syria would be withdrawn imminently. Trump’s surprise decision overturned Washington’s policy in the Middle East. It has also fueled the ambitions and anxieties of local and regional actors vying over the future shape of Syria. Many experts proposed that President Trump could mitigate the damage of his withdrawal of U.S. military forces from Syria by using SAC.<ref>https://www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-comments/2019/the-us-withdrawal-from-syria</ref> Many believe the president chose "to replace U.S. ground forces in Syria with personnel from the CIA's '''Special Activities Division'''" and that the process has been underway for months. Already experienced in operations in Syria, the CIA has numerous paramilitary officers who have the skills to operate independently in harms way. And while the CIA lacks the numbers to replace all 2,000 U.S. military personnel currently in Syria and work along side the [[Syrian Democratic Forces]] (these CIA personnel are spread cross the world), but their model is based on fewer enablers and support.<ref>https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/how-trump-can-salvage-us-interests-in-syria</ref> |

In December 2018, US President [[Donald Trump]] announced that US troops involved in the fight against the [[Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant|Islamic State]] (ISIS) in northeast Syria would be withdrawn imminently. Trump’s surprise decision overturned Washington’s policy in the Middle East. It has also fueled the ambitions and anxieties of local and regional actors vying over the future shape of Syria. Many experts proposed that President Trump could mitigate the damage of his withdrawal of U.S. military forces from Syria by using SAC.<ref>https://www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-comments/2019/the-us-withdrawal-from-syria</ref> Many believe the president chose "to replace U.S. ground forces in Syria with personnel from the CIA's '''Special Activities Division'''" and that the process has been underway for months. Already experienced in operations in Syria, the CIA has numerous paramilitary officers who have the skills to operate independently in harms way. And while the CIA lacks the numbers to replace all 2,000 U.S. military personnel currently in Syria and work along side the [[Syrian Democratic Forces]] (these CIA personnel are spread cross the world), but their model is based on fewer enablers and support.<ref>https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/how-trump-can-salvage-us-interests-in-syria</ref> |

||

On October 26, 2019 U.S. [[Joint Special Operations Command]]'s (JSOC) [[Delta Force]] conducted a raid into the Idlib province of Syria on the border with Turkey that resulted in the death of brahim Awad Ibrahim Ali al-Badri al-Samarrai also known as [[Abū Bakr al-Baghdadi]]. <ref>https://www.cnn.com/2019/10/26/politics/white-house-trump-announcement-sunday/index.html</ref> The raid was launched based on a [[CIA]] Special Activities Division's intelligence collection and close target reconnaissance effort that located the leader of ISIS. This complex operations was conducted during the withdrawal of U.S. forces northeast Syria, adding to the complexity. <ref>https://www.ibtimes.com/isis-leader-al-baghdadi-dead-after-us-special-forces-raid-hideout-syria-sources-2854504</ref><ref>https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/us-forces-launch-operation-in-syria-targeting-isis-leader-baghdadi-officials-say/2019/10/27/081bc257-adf1-4db6-9a6a-9b820dd9e32d_story.html</ref> Several senior officials commented that this operation was only possible because of the presence of troops on the ground allowing for the development of intelligence networks. Any further reduction in troop presence could compromise this capability. The Syrian Democratic Forces and the Iraqi military also support the operation. The U.S. stated they deconflicted with Turkey, but they did not support the operation.<ref>https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2019/10/27/isis-leader-al-baghdadi-believed-killed-in-us-commando-raid/</ref> |

|||

==Worldwide mission== |

==Worldwide mission== |

||

Revision as of 12:36, 27 October 2019

The Special Activities Center (SAC) is a division of the United States Central Intelligence Agency responsible for covert operations. The unit was named Special Activities Division prior to 2016.[1] Within SAC there are two separate groups: SAC/SOG (Special Operations Group) for tactical paramilitary operations and SAC/PAG (Political Action Group) for covert political action.[2]

The Special Operations Group (SOG) is a department within SAC responsible for operations that include high-threat military or covert operations with which the U.S. government does not wish to be overtly associated.[3] As such, unit members, called Paramilitary Operations Officers and Specialized Skills Officers, do not typically carry any objects or clothing, e.g., military uniforms, that would associate them with the United States government.[4]

If they are compromised during a mission, the United States government may

SOG Paramilitary Operations Officers account for a majority of Distinguished Intelligence Cross and Intelligence Star recipients during conflicts or incidents which elicited CIA involvement. These are the highest and third highest valor awards in the CIA. An award bestowing either of these citations represents the highest honors awarded within the CIA in recognition of distinguished valor and excellence in the line of duty. SAC/SOG operatives also account for the majority of the stars displayed on the Memorial Wall at CIA headquarters indicating that the officer died while on active duty.[7] The motto of SAC is Tertia Optio, which means Third Option, as covert action is the option with diplomacy and the military.[8]

The Political Action Group (PAG) is responsible for covert activities related to political influence, psychological operations, and economic warfare. The rapid development of technology has added cyber warfare to their mission. Tactical units within SAC are also capable of carrying out covert political action while deployed in hostile and austere environments. A large covert operation typically has components that involve many or all of these categories as well as paramilitary operations.

Political and "influence" covert operations are used to support U.S. foreign policy. Overt support for one element of an insurgency would often be counterproductive due to the impression it would potentially exert on the local population. In such cases covert assistance allows the U.S. to assist without damaging these elements in the process.

Overview

SAC provides the

As the action arm of the

The political action group within SAC conducts the deniable

Propaganda includes leaflets, newspapers, magazines, books, radio, and television, all of which are geared to convey the U.S. message appropriate to the region. These techniques have expanded to cover the internet as well. They may employ officers to work as journalists, recruit agents of influence, operate media platforms, plant certain stories or information in places it is hoped it will come to public attention, or seek to deny and/or discredit information that is public knowledge. In all such propaganda efforts, "black" operations denote those in which the audience is to be kept ignorant of the source; "white" efforts are those in which the originator openly acknowledges themselves; and "gray" operations are those in which the source is partly but not fully acknowledged.[16][17]

Some examples of political action programs were the prevention of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) from winning elections between 1948 and the late 1960s; overthrowing the governments of Iran in 1953 and Guatemala in 1954; arming rebels in Indonesia in 1957; and providing funds and support to the trade union federation Solidarity following the imposition of martial law in Poland after 1981.[18]

SAC's existence became better known as a result of the "

There remains some conflict between the Directorate of Operations (CIA) and the more clandestine parts of the United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM),[25] such as the Joint Special Operations Command. This is usually confined to the civilian/political heads of the respective Department/Agency. The combination of SAC and USSOCOM units has resulted in some of the more prominent actions of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, including the locating and killing of Osama bin Laden.[24][26] SAC/SOG has several missions. One of these missions is the recruiting, training, and leading of indigenous forces in combat operations.[24] SAC/SOG and its successors have been used when it was considered desirable to have plausible deniability about U.S. support (this is called a covert operation or "covert action").[15] Unlike other special missions units, SAC/SOG operatives combine special operations and clandestine intelligence capabilities in one individual.[11] These individuals can operate in any environment (sea, air or ground) with limited to no support.[9]

Covert action

Under U.S. law, the CIA is authorized to collect intelligence, conduct counterintelligence and to conduct

The Pentagon commissioned a study to determine whether the CIA or the

Selection and training

SAC/SOG has several hundred officers, mostly former members of

There are four principal elements within SAC's Special Operations Group: the Air Branch, the Maritime Branch, the Ground Branch, and the Armor and Special Programs Branch. The Armor and Special Programs Branch is charged with development, testing, and covert procurement of new personnel and vehicular armor and maintenance of stockpiles of ordnance and weapons systems used by SOG, almost all of which must be obtained from clandestine sources abroad, in order to provide SOG operatives and their foreign trainees with plausible deniability in accordance with U.S. Congressional directives.

Together, the SAC/SOG comprises a complete combined arms covert paramilitary force. Paramilitary Operations Officers are the core of each branch and routinely move between the branches to gain expertise in all aspects of SOG.[31] As such, Paramilitary Operations Officers are trained to operate in a multitude of environments. Because these officers are taken from the most highly trained units in the U.S. military and then provided with extensive additional training to become CIA clandestine intelligence officers, many U.S. security experts assess them as the most elite of the U.S. special missions units.[32]

SAC, like most of the CIA, requires a

History

World War II

While the

From 1943 to 1945, the OSS also played a major role in training

One of the OSS' greatest accomplishments during World War II was its penetration of

OSS Paramilitary Officers parachuted into many countries that were behind enemy lines, including France, Norway, Greece, and the Netherlands. In Crete, OSS paramilitary officers linked up with, equipped and fought alongside

OSS was disbanded shortly after World War II, with its intelligence analysis functions moving temporarily into the U.S. Department of State. Espionage and counterintelligence went into military units, while paramilitary and other covert action functions went into the Office of Policy Coordination set up in 1948. Between the original creation of the CIA by the National Security Act of 1947 and various mergers and reorganizations through 1952, the wartime OSS functions generally ended up in CIA. The mission of training and leading guerrillas in due course went to the United States Army Special Forces, but those missions required to remain covert were performed by the (Deputy) Directorate of Plans and its successor the Directorate of Operations of the CIA. In 1962, the paramilitary operations of CIA centralized in the Special Operations Division (SOD), the predecessor of SAC. The direct descendant of the OSS' Special Operations is the CIA's Special Activities Division.

Tibet

After the Chinese invasion of Tibet in October 1950, the CIA inserted paramilitary (PM) teams into Tibet to train and lead

According to a book by retired CIA officer John Kenneth Knaus, entitled Orphans Of The Cold War: America And The Tibetan Struggle For Survival, Gyalo Thondup, the older brother of the 14th (and current) Dalai Lama, sent the CIA five Tibetan recruits. These recruits were trained in paramilitary tactics on the island of

Korea

The CIA sponsored a variety of activities during the

These were the first maritime

Cuba (1961)

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (known as "La Batalla de Girón", or "Playa Girón" in Cuba), was an unsuccessful attempt by a U.S.-trained force of Cuban exiles to invade southern Cuba and overthrow the Cuban government of Fidel Castro. The plan was launched in April 1961, less than three months after John F. Kennedy assumed the presidency of the United States. The Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces, trained and equipped by Eastern Bloc nations, defeated the exile-combatants in three days.

The sea-borne invasion force landed on April 17, and fighting lasted until April 19, 1961. CIA Paramilitary Operations Officers

Bolivia

The

Vietnam and Laos

The original OSS mission in Vietnam under Major Archimedes Patti was to work with Ho Chi Minh in order to prepare his forces to assist the United States and their Allies in fighting the Japanese. After the end of World War II, the U.S. agreed at Potsdam to turn Vietnam back to their previous French rulers and in 1950 the U.S. began providing military aid to the French.[54]

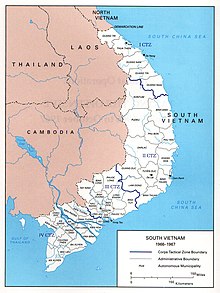

CIA Paramilitary Operations Officers trained and led Hmong tribesmen in Laos and Vietnam, and the actions of these officers were not known for several years. Air America was the air component of the CIA's paramilitary mission in Southeast Asia and was responsible for all combat, logistics and search and rescue operations in Laos and certain sections of Vietnam.[55] The ethnic minority forces numbered in the tens of thousands. They conducted direct actions mission, led by Paramilitary Operations Officers, against the communist Pathet Lao forces and their North Vietnamese allies.[9]

Elements of the Special Operations Division were seen in the CIA's Phoenix Program. One component of the Phoenix Program was involved in the capture and killing of suspected Viet Cong (National Liberation Front – NLF) members.[56] Between 1968 and 1972, the Phoenix Program captured 81,740 National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (NLF or Viet Cong) members, of whom 26,369 were killed. This was a large proportion of U.S. killings between 1969 and 1971. The program was also successful in destroying their infrastructure. By 1970, communist plans repeatedly emphasized attacking the government's "pacification" program and specifically targeted Phoenix agents. The NLF also imposed quotas. In 1970, for example, communist officials near Da Nang in northern South Vietnam instructed their agents to "kill 400 persons" deemed to be government "tyrant[s]" and to "annihilate" anyone involved with the "pacification" program. Several North Vietnamese officials have made statements about the effectiveness of Phoenix.[57][58]

MAC-V SOG (

On May 22, 2016, the CIA honored three paramilitary officers with stars on the memorial wall 56 years after their deaths. They were David W. Bevan, Darrell A. Eubanks and John S. Lewis, all young men, killed on a mission to resupply anti-Communist forces in Laos. They were all recruited from the famous

Maritime activities against the U.S.S.R.

In 1973, SAC/SOG and the CIA's Directorate of Science and Technology built and deployed the

Also in the 1970s, the

CIA officials were always on the lookout for Soviet military equipment captured by the Israelis in the Middle East or abandoned by Libyans in Chad. [citation needed] But the reason the Pentagon spent so much in the covert weapons buying operation was its desire for newer systems, some not previously shipped outside Moscow's alliance. [citation needed] Washington also hoped that Soviet officials would remain, for a time at least, unaware of their loss. [citation needed]

The operation had started in the late 1970s with a relatively small purchase from

The United States made its first purchases from Poland in the early 1980s, paying $20 million to $30 million (roughly $84 million today) to acquire more than 1,000 shoulder-fired antiaircraft rockets and portable launchers. The rockets were routed to Islamic guerrillas in Afghanistan, who used them to shoot down Russian helicopters and cargo planes. (In 1986, the CIA gave the rebels the more effective American-made

Nicaragua

In 1979, the U.S.-backed

The Boland Amendment was a compromise because the

El Salvador

CIA personnel were also involved in the

Somalia

SAC sent in teams of Paramilitary Operations Officers into Somalia prior to the U.S. intervention in 1992. On December 23, 1992, Paramilitary Operations Officer Larry Freedman became the first casualty of the conflict in Somalia. Freedman was a former Army Delta Force operator who had served in every conflict that the U.S. was involved in, both officially and unofficially, since Vietnam.[76] Freedman was killed while conducting special reconnaissance in advance of the entry of U.S. military forces. His mission was completely voluntary, but it required entry into a very hostile area without any support. Freedman was posthumously awarded the Intelligence Star on January 5, 1993 for his "extraordinary heroism".[77]

SAC/SOG teams were key in working with JSOC and tracking high-value targets (HVT), known as "Tier One Personalities". Their efforts, working under extremely dangerous conditions with little to no support, led to several very successful joint JSOC/CIA operations.[78] In one specific operation, a CIA case officer, Michael Shanklin[79] and codenamed "Condor", working with a CIA Technical Operations Officer from the Directorate of Science and Technology, managed to get a cane with a beacon in it to Osman Ato, a wealthy businessman, arms importer, and Mohammed Aideed, a money man whose name was right below Mohamed Farrah Aidid's on the Tier One list.

Once Condor confirmed that Ato was in a vehicle,

a

Blackhawks [sic], surrounded the car and handcuffed Ato. It was the first known helicopter takedown of suspects in a moving car. The next time Jones saw the magic cane, an hour later, Garrison had it in his hand. "I like this cane," Jones remembers the general exclaiming, a big grin on his face. "Let's use this again." Finally, a tier one personality was in custody.[78]

President Bill Clinton withdrew U.S. forces on May 4, 1994.[80]

In June 2006, the

In 2009, PBS reported that al-Qaeda had been training terrorists in Somalia for years. Until December 2006, Somalia's government had no power outside of the town of Baidoa, 150 miles (240 km) from the capital. The countryside and the capital were run by warlords and militia groups who could be paid to protect terrorist groups.[81]

CIA officers kept close tabs on the country and paid a group of Somali warlords to help hunt down members of al-Qaeda according to The New York Times.[citation needed] Meanwhile, Ayman al-Zawahiri, the deputy to al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, issued a message calling for all Muslims to go to Somalia.[81] On January 9, 2007, a U.S. official said that ten militants were killed in one airstrike.[82]

On September 14, 2009,

From 2010 to 2013, the CIA set up the Somalia

Significant events during this time frame included the targeted drone strikes against British al-Qaida operative

Afghanistan

During the

SAC paramilitary teams were active in Afghanistan in the 1990s in clandestine operations to locate and kill or capture

On September 26, 2001, members of the Special Activities Division, led by Gary Schroen, were the first U.S. forces inserted into Afghanistan. The Northern Afghanistan Liaison Team entered the country nine days after the 9/11 attack[94][95] and linked up with the Northern Alliance as part of Task Force Dagger.[96]

They provided the Northern Alliance with resources including cash to buy weapons and prepared for the arrival of USSOCOM forces. The plan for the invasion of Afghanistan was developed by the CIA, the first time in United States history that such a large-scale military operation was planned by the CIA.[97] SAC, U.S. Army Special Forces, and the Northern Alliance combined to overthrow the Taliban in Afghanistan with minimal loss of U.S. lives. They did this without the use of conventional U.S. military ground forces.[15][98][99][100]

The Washington Post stated in an editorial by John Lehman in 2006:

What made the Afghan campaign a landmark in the U.S. Military's history is that it was prosecuted by Special Operations forces from all the services, along with Navy and Air Force tactical power, operations by the Afghan Northern Alliance and the CIA were equally important and fully integrated. No large Army or Marine force was employed.[101]

In a 2008

The valor exhibited by Afghan and American soldiers, fighting to free Afghanistan from a horribly cruel regime, will inspire even the most jaded reader. The stunning victory of the horse soldiers – 350 Special Forces soldiers, 100 C.I.A. officers and 15,000 Northern Alliance fighters routing a Taliban army 50,000 strong – deserves a hallowed place in American military history.[102]

Small and highly agile paramilitary mobile teams spread out over the countryside to meet with locals and gather information about the Taliban and al-Qa'ida. During that time, one of the teams was approached in a village and asked by a young man for help in retrieving his teenage sister. He explained that a senior Taliban official had taken her as a wife and had sharply restricted the time she could spend with her family. The team gave the man a small hand-held tracking device to pass along to his sister, with instructions for her to activate it when the Taliban leader returned home. As a result, the team captured the senior Taliban official and rescued the sister.[103]

Tora Bora

In December 2001, SAC/SOG and the Army's Delta Force tracked down Osama bin Laden in the rugged mountains near the Khyber Pass in Afghanistan.[104] Former CIA station chief Gary Berntsen as well as a subsequent Senate investigation claimed that the combined American special operations task force was largely outnumbered by al-Qaeda forces and that they were denied additional U.S. troops by higher command.[105] The task force also requested munitions to block the avenues of egress of bin Laden, but that request was also denied.[106] The SAC team was unsuccessful and "Bin Laden and bodyguards walked uncontested out of Tora Bora and disappeared into Pakistan's unregulated tribal area."[107] At Bin Laden's abandoned encampment, the team uncovered evidence that bin Laden's ultimate aim was to obtain and detonate a nuclear device in the United States.[97]

Surge

In September 2009, the CIA planned on "deploying teams of spies, analysts and paramilitary operatives to Afghanistan, part of a broad intelligence 'surge' ordered by President Obama. This will make its station there among the largest in the agency's history."[108] This presence is expected to surpass the size of the stations in Iraq and Vietnam at the height of those wars.[108] The station is located at the U.S. Embassy in Kabul and is led "by a veteran with an extensive background in paramilitary operations".[109] The majority of the CIA's workforce is located among secret bases and military special operations posts throughout the country.[109][110]

Also in 2009, General

The End Game

According to the current and former intelligence officials, General McChrystal also had his own preferred candidate for the Chief of Station (COS) job, a good friend and decorated CIA paramilitary officer (who is now known to be Greg Vogle).[112][113] The officer had extensive experience in war zones, including two previous tours in Afghanistan with one as the Chief of Station, as well as tours in the Balkans, Baghdad and Yemen. He is well known in CIA lore as "the man who saved Hamid Karzai's life when the CIA led the effort to oust the Taliban from power in 2001". President Karzai is said to be greatly indebted to this officer and was pleased when the officer was named chief of station again. According to interviews with several senior officials, this officer "was uniformly well-liked and admired. A career paramilitary officer, he came to the CIA after several years in an elite Marine unit".[112][114]

General McChrystal's strategy included the lash up of special operations forces from the U.S. Military and from SAC/SOG to duplicate the initial success and the defeat of the Taliban in 2001[115] and the success of the "Surge" in Iraq in 2007.[116] This strategy proved highly successful and worked very well in Afghanistan with SAC/SOG and JSOC forces conducting raids nearly every night having "superb results" against the enemy.[117]

In 2001, the CIA's SAC/SOG began creating what would come to be called Counter-terrorism Pursuit Teams (CTPT).[118][119] These units grew to include over 3,000 operatives by 2010 and have been involved in sustained heavy fighting against the enemy. It is considered the "best Afghan fighting force".

Located at 7,800 feet (2,400 m) above sea level, Firebase Lilley in

This covert war also includes a large SOG/CTPT expansion into Pakistan to target senior al-Qaeda and Taliban leadership in the Federally Administered Tribal Area (FATA).[121] CTPT units are the main effort in both the "Counterterrorism plus" and the full "Counterinsurgency" options being discussed by the Obama administration in the December 2010 review.[122] SOG/CTPT are also key to any exit strategy for the U.S. government to leave Afghanistan, while still being able to deny al-Qaeda and other trans-national extremists groups a safehaven both in Afghanistan and in the FATA of Pakistan.[123]

In January 2013, a CIA drone strike killed Mullah Nazir a senior Taliban commander in the South Waziristan area of Pakistan believed responsible for carrying out the insurgent effort against the U.S. military in Afghanistan. Nazir's death degraded the Taliban.[124]

The U.S. has decided to lean heavily on CIA in general and SAC specifically in their efforts to withdraw from Afghanistan as it did in Iraq.[125] There are plans being considered to have several U.S .Military special operations elements assigned to CIA after the withdrawal. If so, there would still be a chance to rebuild and assist and coordinate (with Afghan ANSF commandos) and continue to keep a small footprint while allowing free elections and pushing back the Taliban/AQ forces that have failed but continue to attempt their taking back parts of the country, as they have had between 2015 through 2016.[126]

The Trump administration doubled down on the covert war in Afghanistan by increasing the number of paramilitary officers from SAC fighting along side and leading the Afghan CTPT's, supported by Omega Teams from JSOC. Combined they are considered the most effective units in Afghanistan and the lynchpin of the counter insurgency and counter-terrorism effort. The war has been largely turned over to SAC.[127] On October 21, 2016, two senior paramilitary officers, Brian Hoke and Nate Delemarre, were killed during a CTPT operation in Jalalabad, Afghanistan. The two longtime friends were killed fighting side-by-side against the Taliban and buried next to each other at Arlington National Cemetery.[128]

Yemen

On November 5, 2002, a missile launched from a CIA-controlled Predator drone killed al-Qaeda members traveling in a remote area in Yemen. SAC/SOG paramilitary teams had been on the ground tracking their movements for months and called in this air strike.[129] One of those in the car was Ali Qaed Senyan al-Harthi, al-Qaeda's chief operative in Yemen and a suspect in the October 2000 bombing of the destroyer USS Cole. Five other people, believed to be low-level al-Qaeda members, were also killed to include an American named Kamal Derwish.[130][131] Former Deputy U.S. Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz called it "a very successful tactical operation" and said "such strikes are useful not only in killing terrorists but in forcing al-Qaeda to change its tactics".[130]

"It's an important step that has been taken in that it has eliminated another level of experienced leadership from al-Qaeda," said

In 2009, the Obama administration authorized continued lethal operations in Yemen by the CIA.

Iraq

SAC paramilitary teams entered Iraq before the

In a 2004 U.S. News & World Report article, "A firefight in the mountains", the author states:

Viking Hammer would go down in the annals of Special Forces history – a battle fought on foot, under sustained fire from an enemy lodged in the mountains, and with minimal artillery and air support.[139]

SAC/SOG teams also conducted high risk special reconnaissance missions behind Iraqi lines to identify senior leadership targets. These missions led to the initial assassination attempts against

NATO member Turkey refused to allow its territory to be used by the U.S. Army's 4th Infantry Division for the invasion. As a result, the SAC/SOG, U.S. Army special forces joint teams, the Kurdish Peshmerga and the

The mission that captured Saddam Hussein was called "

CIA paramilitary units continued to team up with the JSOC in Iraq and in 2007 the combination created a lethal force many credit with having a major impact in the success of "the Surge". They did this by killing or capturing many of the key al-Qaeda leaders in Iraq.[146][147] In a CBS 60 Minutes interview, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Bob Woodward described a new special operations capability that allowed for this success. This capability was developed by the joint teams of CIA and JSOC.[148] Several senior U.S. officials stated that the "joint efforts of JSOC and CIA paramilitary units was the most significant contributor to the defeat of al-Qaeda in Iraq".[146][149]

In May 2007, Marine Major Douglas A. Zembiec was serving in SAC Ground Branch in Iraq when he was killed by small arms fire while leading a raid.[150][151] Reports from fellow paramilitary officers stated that the flash radio report sent was "five wounded and one martyred"[152] Major Zembiec was killed while saving his soldiers, Iraqi soldiers. He was honored with an intelligence star for his valor in combat.[153]

On October 26, 2008, SAC/SOG and

In September 2014 with the rise of the

Pakistan

SAC/SOG has been very active "on the ground" inside Pakistan targeting al-Qaeda operatives for

According to the documentary film Drone, by Tonje Schei, since 2002 the

In a National Public Radio (NPR) report dated February 3, 2008, a senior official stated that al-Qaeda has been "decimated" by SAC/SOG's air and ground operations. This senior U.S. counter-terrorism official goes on to say, "The enemy is really, really struggling. These attacks have produced the broadest, deepest and most rapid reduction in al-Qaida senior leadership that we've seen in several years."[168] President Obama's CIA Director Leon Panetta stated that SAC/SOG's efforts in Pakistan have been "the most effective weapon" against senior al-Qaeda leadership.[169][170]

These covert attacks have increased significantly under President Obama, with as many at 50 al-Qaeda militants being killed in the month of May 2009 alone.

On August 6, 2009, the CIA announced that Baitullah Mehsud was killed by a SAC/SOG drone strike in Pakistan.[176] The New York Times said, "Although President Obama has distanced himself from many of the Bush administration's counter-terrorism policies, he has embraced and even expanded the C.I.A.'s covert campaign in Pakistan using Predator and Reaper drones".[176] The biggest loss may be to "Osama bin Laden's al-Qa'ida". For the past eight years, al-Qaeda had depended on Mehsud for protection after Mullah Mohammed Omar fled Afghanistan in late 2001. "Mehsud's death means the tent sheltering Al Qaeda has collapsed," an Afghan Taliban intelligence officer who had met Mehsud many times told Newsweek. "Without a doubt he was Al Qaeda's No. 1 guy in Pakistan," adds Mahmood Shah, a retired Pakistani Army brigadier and a former chief of the Federally Administered Tribal Area, or FATA, Mehsud's base.[177]

Airstrikes from CIA drones struck targets in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan on September 8, 2009. Reports stated that seven to ten militants were killed to include one top al-Qaida leader. He was Mustafa al-Jaziri, an Algerian national described as an "important and effective" leader and senior military commander for al-Qaida. The success of these operations are believed to have caused senior Taliban leaders to significantly alter their operations and cancel key planning meetings.[178][179]

The CIA is also increasing its campaign using Predator missile strikes on al-Qaeda in Pakistan. The number of strikes in 2009 exceeded the 2008 total, according to data compiled by the Long War Journal, which tracks strikes in Pakistan.[109] In December 2009, the New York Times reported that President Obama ordered an expansion of the drone program with senior officials describing the program as "a resounding success, eliminating key terrorists and throwing their operations into disarray".[180] The article also cites a Pakistani official who stated that about 80 missile attacks in less than two years have killed "more than 400" enemy fighters, a number lower than most estimates but in the same range. His account of collateral damage was strikingly lower than many unofficial counts: "We believe the number of civilian casualties is just over 20, and those were people who were either at the side of major terrorists or were at facilities used by terrorists."[180]

On December 6, 2009, a senior al-Qaeda operative, Saleh al-Somali, was killed in a drone strike in Pakistan. He was responsible for their operations outside of the Afghanistan-Pakistan region and formed part of the senior leadership. Al-Somali was engaged in plotting terrorist acts around the world and "given his central role, this probably included plotting attacks against the United States and Europe".[181][182] On December 31, 2009, senior Taliban leader and strong Haqqani ally Haji Omar Khan, brother of Arif Khan, was killed in the strike along with the son of local tribal leader Karim Khan.[183]

In January 2010, al-Qaeda in Pakistan announced that

On February 5, 2010, the Pakistani

On February 20, Muhammad Haqqani, son of Jalaluddin Haqqani, was one of four people killed in the drone strike in Pakistan's tribal region in North Waziristan, according to two Pakistani intelligence sources.[190]

On May 31, 2010, the New York Times reported that Mustafa Abu al Yazid (AKA Saeed al Masri), a senior operational leader for Al Qaeda, was killed in an American missile strike in Pakistan's tribal areas.[191]

From July to December 2010, predator strikes killed 535 suspected militants in the FATA to include Sheikh Fateh Al Misri, Al-Qaeda's new third in command on September 25.[192] Al Misri was planning a major terrorist attack in Europe by recruiting British Muslims who would then go on a shooting rampage similar to what transpired in Mumbai in November 2008.[193]

Operation Neptune Spear

On May 1, 2011, President Barack Obama announced that

The operation in the Bilal military cantonment area in the city of Abbottabad resulted in the acquisition of extensive intelligence on the future attack plans of al-Qaeda.[199][200][201] Bin Laden's body was flown to Afghanistan to be identified and then forwarded to the aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson for a burial at sea.[202] Results from the DNA samples taken Afghanistan were compared with those of a known relative of bin Laden's and confirmed the identity.

The operation was a result of years of intelligence work that included the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), the CIA, the DSS, and the Delta Force's apprehension and interrogation of Khalid Sheik Mohammad (KSM),[203][204][205] the discovery of the real name of the courier disclosed by KSM, the tracking, via signal intelligence, of the courier to the Abbottobad compound by paramilitary operatives and the establishment of a CIA safe house that provided critical advance intelligence for the operation.[206][207][208][208]

The material discovered in the raid indicated that

Iran

In the early 1950s, the Central Intelligence Agency and Britain's

In November 1979, a group of

On March 9, 2007 alleged CIA officer

Libya

After the Arab Spring movements overthrew the rulers of Tunisia and Egypt, its neighbours to the west and east respectively, Libya had a major revolt beginning in February 2011.[223][224] In response, the Obama administration sent in SAC paramilitary operatives to assess the situation and gather information on the opposition forces.[225][226] Experts speculated that these teams could have been determining the capability of these forces to defeat the Muammar Gaddafi regime and whether Al-Qaeda had a presence in these rebel elements.

U.S. officials had made it clear that no U.S. troops would be "on the ground", making the use of covert paramilitary operatives the only alternative.[227] During the early phases of the Libyan offensive of U.S.-led air strikes, paramilitary operatives assisted in the recovery of a U.S. Air Force pilot who had crashed due to mechanical problems.[228][229] There was speculation that President Obama issued a covert action finding in March 2011 that authorizes the CIA to carry out a clandestine effort to provide arms and support to the Libyan opposition.[230]

Syria

CIA paramilitary teams have been deployed to Syria to report on the uprising, to access the rebel groups, leadership and to potentially

Again in 2015, the combination of the U.S. Military's

In December 2018, US President

On October 26, 2019 U.S.

Worldwide mission

The

In the

In 2002, the

SAC/SOG teams have been dispatched to the country of

The SAC/SOG teams have also been active in the Philippines, where 1,200 U.S. military advisers helped to train local soldiers in "counter-terrorist operations" against Abu Sayyaf, a radical Islamist group suspected of ties with al Qaeda. Little is known about this U.S. covert action program, but some analysts believe that "the CIA's paramilitary wing, the Special Activities Division (SAD) [referring to SAC's previous name], has been allowed to pursue terrorist suspects in the Philippines on the basis that its actions will never be acknowledged".[129]

On July 14, 2009, several newspapers reported that DCIA

According to many experts, the Obama administration has relied on the CIA and their paramilitary capabilities, even more than they have on U.S. military forces, to maintain the fight against terrorists in the Afghanistan and Pakistan region, as well as places like Yemen, Somalia and North Africa.[259][260] Ronald Kessler states in his book The CIA at War: Inside the Secret War Against Terror, that although paramilitary operations are a strain on resources, they are winning the war against terrorism.[259][261]

SAC/SOG paramilitary officers executed the clandestine evacuation of U.S. citizens and diplomatic personnel in Somalia, Iraq (during the Persian Gulf War) and Liberia during periods of hostility, as well as the insertion of Paramilitary Operations Officers prior to the entry of U.S. military forces in every conflict since World War II.[262] SAC officers have operated covertly since 1947 in places such as North Korea, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Lebanon, Iran, Syria, Libya, Iraq, El Salvador, Guatemala, Colombia, Mexico, Nicaragua, Honduras, Chile, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Somalia, Kosovo, Afghanistan and Pakistan.[263]

In the

In 2019, Pulitzer Prize finalist Annie Jacobsen's book, "Surprise, Kill, Vanish: The Secret History of CIA Paramilitary Armies, Operators, and Assassins" was released. The author refers to CIA's Special Activities Division as "a highly-classified branch of the CIA and the most effective, black operations force in the world." [265] She further states that every American president since World War II has asked the CIA to conduct sabotage, subversion and assassination.[266]

Innovations in special operations

The

Notable paramilitary officers

- George Bacon

- Morris "Moe" Berg

- William Francis Buckley

- William Colby

- Jerry Daniels

- John Downey

- Richard Fecteau

- James (Jim) Glerum

- Wilbur "Will" Green

- Thomas "Tom" Fosmire

- Howard Freeman

- Richard (Dick) Holm

- Bill Lair

- Lloyd C. "Pat" Landry

- Grayston Lynch

- Michael Patrick Mulroy

- Anthony Poshepny (a.k.a. Tony Poe)

- William "Rip" Robertson

- Felix Rodriguez

- Johnny Micheal Spann

- Gar Thorsrud

- Ernest "Chick" Tsikerdanos

- Michael G. Vickers

- Billy Waugh, Sergeant Major, U.S. Army Retired

- William (Bill) Young

- Leo Camilleri

- Douglas A. Zembiec

- Chris Mueller and William Carlson: On October 25, 2003, paramilitary officers Christopher Mueller and William "Chief" Carlson were killed while conducting an operation to kill/capture high level

Notable political action officers

- Virginia Hall (1906–1982) Goillot started as the only female paramilitary officer in the OSS. She shot herself in the leg while hunting in Turkey in 1932, which was then amputated below the knee. She parachuted into France to organize the resistance with her prosthesis strapped to her body. She was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. She married an OSS officer named Paul Goillot and the two joined the CIA as paramilitary operations officers in SAC. Once aboard, Mrs. Goillot made her mark as a political action officer playing significant roles in the Guatemala and Guyana operations. These operations involved the covert removal of the governments of these two countries, as directed by the President of the United States.[273]

- JFK assassination, and was one of the operatives in the Watergate scandal.[276] Hunt was also a well-known author with over 50 books to his credit. These books were published under several alias names and several were made into motion pictures.[277]

- David Atlee Phillips (1922–1988) Perhaps the most famous propaganda officer ever to serve in CIA, Phillips began his career as a journalist and amateur actor in Buenos Aires, Argentina. He joined the Agency in the 1950s and was one of the chief architects of the operation to overthrow Communist president Arbenz in Guatemala in 1954. He was later heavily engaged as a principal member of the Bay of Pigs Task Force at Langley, and in subsequent anti-Castro operations throughout the 1960s. He founded the Association of Former Intelligence Officers (AFIO) after successfully contesting a libel suit against him.

- Mohammed Mossadegh and returned monarchical rule to Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran, and Iran's Sun Throne in August 1953. He was also the grandson of American president Theodore Roosevelt.

CIA Memorial Wall

The CIA Memorial Wall is located at CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia. It honors CIA employees who died in the line of duty.[278] There are 129 stars carved into the marble wall,[279][280] each one representing an officer. A majority of these were paramilitary officers.[278] A black book, called the "Book of Honor", lies beneath the stars and is encased in an inch-thick plate of glass.[280] Inside this book are stars, arranged by year of death, and the names of 91 employees who died in CIA service alongside them.[278][280][279] The other names remain secret, even in death.[278]

Third Option Foundation (TOF) is a national non-profit organization set up to support the families of fallen paramilitary officers. The name refers to the motto of CIA's Special Activities Center: Tertia Optio, the President's third option when military force is inappropriate and diplomacy is inadequate. TOF provides comprehensive family resiliency programs, financial support for the families of paramilitary officers killed in action and it works behind the scenes to "quietly help those who quietly serve".[281]

In fiction

- In Madam Secretary, Henry McCord (husband of the titular Secretary of State) serves as Director of the CIA's Special Activities Division in Seasons 3 and 4.

See also

- DGSE

- Army Ranger Wing

- Clandestine HUMINT and Covert Action

- Counter-terrorism

- Defense Clandestine Service

- Defense Intelligence Agency

- Delta Force

- Direct action (military)

- Espionage

- Extraordinary rendition by the United States

- Foreign Intelligence Service (Russia)

- Foreign internal defense

- Forward Operating Base Chapman attack

- Guerrilla warfare

- Joint Special Operations Command

- Marine Special Operations Command

- Military Intelligence, Section 6(MI6)

- Plausible deniability

- Special Air Service

- Special Frontier Force

- Special reconnaissance

- Targeted killing

- United States Army Special Forces

- United States Naval Special Warfare Development Group

- United States Special Operations Command

- United States special operations forces

- GRU/FSBcounter-terrorism unit

- Wagner Group

- 486th Flight Test Squadron

Notes

- ^ https://unredacted.com/2015/10/27/first-complete-look-at-the-cias-national-clandestine-service-org-chart/

- ^ a b c d Daugherty (2004)

- Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Woodward, Bob (November 18, 2001). "Secret CIA Units Playing Central Combat Role". Washington Post.

- ^ "Special Operations Forces (SOF) and CIA Paramilitary Operations: Issues for Congress, CRS-2" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 8, 2016.

- ^ Waller, Douglas (February 3, 2003). "The CIA's Secret Army: The CIA's Secret Army". Time. Retrieved January 28, 2018 – via content.Time.com.

- ^ Gup, Ted (2000). The Book of Honor: Cover Lives and Classified Deaths at the CIA.

- ^ "About".

- ^ a b c d e f Southworth (2002)

- ^ "Joint Publication 1-02, Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. October 17, 2008: 512. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 23, 2008. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Douglas, Waller (February 3, 2003). "The CIA's Secret Army". Time.

- ^ Mazzetti, Mark; Helene Cooper (February 26, 2009). "CIA Pakistan Campaign is Working Director Say". New York Times. p. A15.

- ^ a b c Miller, Greg (July 14, 2009). "CIA Secret Program: PM Teams Targeting Al Qaeda". Los Angeles Times. p. A1.

- ^ Mazzetti, Mark; Shane Scott (July 14, 2009). "CIA Had Plan To Assassinate Qaeda Leaders". New York Times. p. A1.

- ^ a b c d e f Coll (2004)

- ^ a b "americanforeignrelations.com"

- ^ "U.S. Aggressiveness towards Iran". Foreign Policy Journal. April 15, 2010.

- ^ Daugherty (2004), p. 83

- ^ a b c d e f Woodward (2004)

- ^ a b c d Tucker (2008)

- ^ Conboy (1999)

- ^ Warner (1996)

- ISBN 978-1610606905. Retrieved May 19, 2011 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d Stone & Williams (2003)

- ^ Vickers, Michael G (June 29, 2006). "Testimony of Michael G. Vickers on SOCOM's Mission and Roles to the House Armed Services Committee's Subcommittee on Terrorism, Unconventional Threats, and Capabilities" (PDF). United States House of Representatives.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Osama bin Laden killed in CIA operation". The Washington Post. May 8, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Daugherty (2004), p. 25

- ^ Daugherty (2004), p. 28

- ^ "CIA, Pentagon reject recommendation on paramilitary operations".

- ^ [1] Archived August 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "CIA Special Operations Group, Special Activities Division". Cia.americanspecialops.com. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ISBN 978-1610606905. Retrieved May 19, 2011 – via Google Books.

- ^ "FAQs – Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "globalsecurity.org: U.S. Special Operations Forces (SOF): Background and Issues for Congress" (PDF). Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ John Pike. "The Dallas Morning News October 27, 2002". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "Paramilitary Operations Officer/Specialized Skills Officer". Archived from the original on January 30, 2012.

- ^ Wild Bill Donovan: The Last Hero, Anthony Cave Brown, New York City, Times Books, 1982

- ^ "Chef Julia Child, others part of World War II spy network". Archived from the original on August 14, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-14., CNN, August 14, 2008

- ^ a b The CIA's Secret War in Tibet, Kenneth Conboy, James Morrison, The University Press of Kansas, 2002.

- ISBN 978-0-8144-0983-1. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-58542-348-4. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

- ^ Joseph Fitsanakis (March 14, 2009). "CIA veteran reveals agency's operations in Tibet". intelNews.org. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- ISBN 1-891620-85-1

- ^ a b "Korean War: CIA-Sponsored Secret Naval Raids". History Net. June 12, 2006. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Lynch (2000), pp. 83, 129

- ^ Triay (2001)

- ^ "Secrets of History – The C.I.A. in Iran – A special report. How a Plot Convulsed Iran in '53 (and in '79)". The New York Times. April 16, 2000. Retrieved November 3, 2006.

- ISBN 0804768161

- ^ Lazo, Mario, Dagger in the Heart: American Policy Failures in Cuba (1970), Twin Circle Publishing, New York

- ^ Selvage 1985.

- ^ Anderson 1997, p. 693.

- ^ a b c Rodriguez (1989)

- ^ "Death of Che Guevara". Gwu.edu. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "The History Place – Vietnam War 1945-1960".

- ^ Air America and The Ravens by Chris Robbins. Both are the history of CIA/IAD's war in Laos, providing biographies and details on such CIA Paramilitary Officers as Wil Green, Tony Poe, Jerry Daniels, Howie Freeman, Bill Lair, and the pilots, ground crew and support personnel managed by IAD/SOG/Air Branch under the proprietaries Bird Air, Southern Air Transport, China Air Transport and Air America – and the U.S. Air Force forward air controllers (RAVENS) who were brought in under CIA/IAD command and control as "civilians" to support secret combat ops in Laos.

- ISBN 978-0595007387.

- ^ "US Army Combined Arms Center and Fort Leavenworth" (PDF). army.mil. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ^ ^ Colby, William; Peter Forbath (1978) (extract concerning Gladio stay-behind operations in Scandinavia). Honorable Men: My Life in the CIA. London: Hutchinson.

- ^ Shooting at the Moon by Roger Warner, The history of CIA/IAD'S 15-year involvement in conducting the secret war in Laos, 1960–1975, and the career of CIA PMCO (paramilitary case officer) Bill Lair.

- ^ a b Shapira, Ian (June 18, 2017). "They were smokejumpers when the CIA sent them to Laos. They came back in caskets". Retrieved January 28, 2018 – via www.WashingtonPost.com.

- ^ a b Sontag and Drew, Blind Man's Bluff. New York: Public Affairs (1998), p. 196

- ISBN 0-89096-764-4.

- ^ PBS, "The Glomar Explorer" Scientific American Frontiers, Mysteries of the Deep: Raising Sunken Ships, p. 2

- ISBN 0-06-103004-X.

- ^ Sewell (2005) Russian Strategic Nuclear Forces, Center for Arms Control Studies, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, edited by Pavel Podvig

- ^ Sewell (2005) Minutes of the Sixth Plenary Session, USRJC, Moscow, August 31, 1993

- ISBN 0-06-103004-X.

- ISBN 0-06-103004-X.

- ^ [2] Archived February 17, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 978-0-8090-9613-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-671-60117-1.

- JSTOR 3480586.

- ISBN 978-0-312-36272-0.

- ^ Thomas Blanton; Peter Kornbluh (December 5, 2004). "Prisoner Abuse: Patterns from the Past". The National Security Archive.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Tom Gibb (January 27, 2005). "Salvador Option Mooted for Iraq". BBC News.

- ^ Michael Robert Patterson. "Lawrence N. Freedman, Sergeant Major, United States Army". Arlingtoncemetery.net. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-385-49293-5.

- ^ a b Loeb, Vernon (February 27, 2000). "The CIA in Somalia". The Washington Post Magazine. After-Action Report (column). p. W.06. Archived from the original on May 19, 2007. Retrieved July 5, 2013. (Subscription required for the original.)

- ^ Loeb, Vernon (April 29, 2001). "Confessions of a Hero". The Washington Post. p. F.01. Archived from the original on April 29, 2001. Retrieved July 5, 2013. (Subscription required for the original.)

- ^ Patman, R.G. (2001). "Beyond 'the Mogadishu Line': Some Australian Lessons for Managing Intra-State Conflicts", Small Wars and Insurgencies, Vol, 12, No. 1, p. 69

- ^ a b c "NewsHour Extra: U.S. Goes After al-Qaida Suspects in Somalia". Pbs.org. January 10, 2007. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Strikes In Somalia Reportedly Kill 31". January 8, 2007.

- ^ a b Bill RoggioSeptember 15, 2009 (September 15, 2009). "Commando raid in Somalia is latest in covert operations across the globe". The Long War Journal. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Bill RoggioSeptember 14, 2009 (September 14, 2009). "Senior al Qaeda leader killed in Somalia". The Long War Journal. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Bill RoggioJanuary 8, 2007 (January 8, 2007). "U.S. Gunship fires on al Qaeda Leader and Operative in Somalia". The Long War Journal. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Operation Celestial Balance" – via YouTube.

- ^ "Somalia's NISA and CIA: An Effective Partnership Against AlQaeda".

- ^ Somalia: Over 25 Dead and 40 Injured in Mogadishu Courthouse Siege. allAfrica.com (2013-04-15). Retrieved on 2014-05-24.

- ^ Ian Cobain (January 22, 2012). "British 'al-Qaida member' killed in US drone attack in Somalia". the Guardian.

- ^ "Moroccan jihadist killed in Somalia airstrike". February 24, 2012.

- ^ "Navy SEALs rescue kidnapped aid workers Jessica Buchanan and Poul Hagen Thisted in Somalia". Washington Post.

- ^ "U.S. Somalia raid is shape of war to come". UPI.

- ISBN 978-0-87113-854-5.

- ^ "Wayback Machine" (PDF). October 1, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 1, 2006. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ^ Moore, J. Daniel. "First In: An Insider's Account of How the CIA Spearheaded the War on Terror in Afghanistan". Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- ^ "Jawbreaker – CIA Special Activities Division". Retrieved September 11, 2015.

- ^ a b "CIA Confidential: Hunt for Bin Laden". National Geographic Channel. Archived from the original on February 13, 2010. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Schroen, Gary (2005). First In: An insiders account of how the CIA spearheaded the War on Terror in Afghanistan.

- ISBN 978-0-307-23740-8.

- ^ Woodward, Bob (2002) Bush at War, Simon & Schuster, Inc.

- ^ Washington Post editorial, John Lehman former Secretary of the Navy, October 2008

- ^ Barcott, Bruce (May 17, 2009). "Special Forces". The New York Times. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ National Clandestine Service (NCS) – Central Intelligence Agency Archived October 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Cia.gov. Retrieved on 2014-05-24.

- ISBN 0-307-35106-8, Published December 24, 2006 (paperback).

- ^ Scott Shane (November 28, 2009). "Senate Report Explores 2001 Escape by bin Laden From Afghan Mountains". The New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- ^ Fury, Dalton (writer), Kill Bin Laden, p. 233, published October 2008.

- ^ Moore, Tina (November 29, 2009). "Bush administration could've captured terrorist Osama Bin Laden in December 2001: Senate report". NY Daily News.

- ^ a b Miller, Greg (September 20, 2009). "CIA expanding presence in Afghanistan". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Miller, Greg (September 20, 2009). "CIA expanding presence in Afghanistan". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ Mazzetti, Mark (January 1, 2010). "C.I.A. Takes On Bigger and Riskier Role on Front Lines". The New York Times. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ a b "This Week at War: Send in the Spies". Foreign Policy. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Cole, Matthew (February 19, 2010). "CIA'S Influence Wanes in Afghanistan War, Say Intelligence Officials". ABC News. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "The CIA honored the officer who saved Hamid Karzai's life". Newsweek. September 18, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ^ Jaffe, Greg (July 24, 2010). "Gen. Stanley A. McChrystal's retirement ceremony marked by laughter and regret". The Washington Post.

- ^ "McChrystal exit must be followed by new strategy". SeacoastOnline.com. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Woodward, Bob. (2008) The War Within: A Secret White House History 2006–2008 Simon and Schuster

- ^ Obama's Wars, Bob Woodward, Simon and Schuster, 2010 p. 355.

- ^ Whitlock, Craig (September 22, 2010). "Book tells of secret CIA teams staging raids into Pakistan". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on February 22, 2011.

- ^ a b c Whitlock, Craig; Miller, Greg (September 23, 2010). "Paramilitary force is key for CIA". The Washington Post.

- ^ Obama's Wars, Bob Woodward, Simon and Schuster, 2010 p. 8

- ^ Obama's Wars, Bob Woodward, Simon and Schuster, 2010 p. 367

- ^ Obama's Wars, Bob Woodward, Simon and Schuster, 2010 p. 160

- ^ Devine, Jack (July 29, 2010). "The CIA Solution for Afghanistan". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "'Good Taliban' leader Mullah Nazir killed in US drone strike". January 3, 2013.

- ^ "CIA digs in as Americans withdraw from Iraq, Afghanistan". Washington Post.

- ^ CIA could control forces in 'Stan after 2014 | Army Times. armytimes.com. Retrieved on 2014-05-24.

- ^ Gibbons-Neff, Thomas; Schmitt, Eric; Goldman, Adam (October 22, 2017). "A Newly Assertive C.I.A. Expands Its Taliban Hunt in Afghanistan". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ^ Goldman, Adam; Rosenberg, Matthew (September 6, 2017). "A Funeral of 2 Friends: C.I.A. Deaths Rise in Secret Afghan War". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ^ a b c Haynes, Deborah (November 10, 2002). "Al-Qaeda stalked by the Predator". The Times. London. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ a b "U.S. kills al-Qaeda suspects in Yemen". USA Today. November 5, 2002.

- ^ Priest, Dana (January 27, 2010). "U.S. military teams, intelligence deeply involved in aiding Yemen on strikes". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Exclusive: CIA Aircraft Kills Terrorist". Abcnews.go.com. May 13, 2005. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "The Predator". CBS News. January 7, 2003.

- ^ "CIA 'killed al-Qaeda suspects' in Yemen". BBC News. November 5, 2002.

- ^ a b Priest, Dana (January 27, 2010). "U.S. military teams, intelligence deeply involved in aiding Yemen on strikes". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ Amanullah, Zahed (December 30, 2009). "Al-Awlaki, a new public enemy". The Guardian. London. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ "Same US military unit that got Osama bin laden killed Anwar al-Awlaki". Telegraph.co.uk. September 30, 2011.

- ^ a b "A firefight in the mountains: Operation Viking Hammer was one for the record books". US News and World Report. Archived from the original on November 13, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ a b c "A firefight in the mountains: Operation Viking Hammer was one for the record books". US News and World Report. March 28, 2004. Archived from the original on November 13, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ a b "Operation Hotel California: The Clandestine War Inside Iraq". Cia.gov. July 2, 2010. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Jeffrey Fleishman (April 27, 2003). "Militants' crude camp casts doubt on U.S. claims". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "An interview on public radio with the author". WAMU radio. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "Behind lines, an unseen war," Faye Bowers, Christian Science Monitor, April 2003.

- ^ a b 'Black ops' shine in Iraq War, VFW Magazine, Feb, 2004, Tim Dyhouse.

- ^ "Saddam 'caught like a rat' in a hole". CNN.com. December 15, 2003.

- ^ a b Woodward, Bob. (2008) The War Within: A Secret White House History 2006–2008. Simon and Schuster

- ^ "Secret killing program is key in Iraq, Woodward says". CNN. September 9, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Bob Woodward "60 Minutes" Highlights". YouTube. September 7, 2008. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "New U.S. Commander In Afghanistan To Be Tested". NPR. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Gibbons-Neff, Thomas (July 15, 2014). "Legendary Marine Maj. Zembiec, the 'Lion of Fallujah,' died in the service of the CIA". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- ^ Warden, James (February 2, 2008). "Helipad renamed to honor Marine". Stars and Stripes.

- ^ Rubin, Alissa J. (February 1, 2008). "Comrades Speak of Fallen Marine and Ties That Bind". New York Times.

- ^ "Legendary Marine Maj. Zembiec, the 'Lion of Fallujah,' died in the service of the CIA". Washington Post.

- ^ "US choppers attack Syrian village near Iraq border". International Herald Tribune. October 26, 2008. Archived from the original on October 29, 2008. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ^ "Syria: U.S. Attack Kills 8 In Border Area: Helicopters Raid Farm In Syrian Village; Al Qaeda Officer Was Target Of Rare Cross-Border attack". CBS News. October 26, 2008. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ^ "U.S. Official: Unclear If Al Qaeda Coordinator Killed in Syria Raid". Fox News. Archived from the original on October 28, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- ^ Schmitt, Eric; Shanker, Thom (October 27, 2008). "Officials Say U.S. Killed an Iraqi in Raid in Syria". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ^ a b "David Ignatius: U.S. boots are already on the ground against the Islamic State". Washington Post.

- ^ Dion Nissenbaumm, Joe Parkinson (August 11, 2014). "U.S. Giving Aid to Iraqi Kurds Battling Islamic State, or ISIS". WSJ. Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Secret U.S. Unit Trains Commandos in Pakistan," Eric Schmit and Jane Perlez, New York Times, February 22, 2009

- ^ "Unleashed CIA Zapped 8 Qaeda Lieutenants Since July". Daily News. New York. January 18, 2009. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011.

- ^ Alderson, Andrew (November 22, 2008). "British terror mastermind Rashid Rauf 'killed in US missile strike'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ Washington, The (January 16, 2009). "U.S. strikes more precise on al Qaeda". Washington Times. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "The Meaning of al Qaeda's Double Agent". The Wall Street Journal. January 7, 2010.

- ^ "U.S. missile strikes signal Obama tone: Attacks in Pakistan kill 20 at suspected terror hideouts," by R. Jeffrey Smith, Candace Rondeaux, Joby Warrick, Washington Post, Saturday, January 24, 2009

- ^ "Pakistan: Suspected U.S. Missile Strike Kills 27". Fox News. Archived from the original on February 15, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ Chris Woods (April 14, 2014). "CIA's Pakistan drone strikes carried out by regular US air force personnel". The Guardian. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Officials: Al-Qaida Leadership Cadre 'Decimated'". npr.org. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ^ CIA Pakistan Campaign is Working Director Say, Mark Mazzetti and Helene Cooper, New York Times, February 26, 2009, p. A15.

- ^ Gerstein, Josh. "CIA Director Panetta Warns Against Politicization". NBC New York. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ https://news.yahoo.com/s/nm/20090516/ts_nm/us_pakistan_missile. Retrieved May 23, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)[dead link] - ^ "25 Militants Are Killed in Attack in Pakistan". The New York Times. May 17, 2009. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ Ignatius, David (April 25, 2010). "Leon Panetta gets the CIA back on its feet". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Airstrikes Kill Dozens of Insurgents," Joby Warrick, Washington Post, June 24, 2009

- ^ Kelly, Mary Louise (July 22, 2009). "Bin Laden Son Reported Killed In Pakistan". NPR.org.

- ^ a b Mark Mazzetti, Eric P. Schmitt (August 6, 2009). "C.I.A. Missile Strike May Have Killed Pakistan's Taliban Leader, Officials Say". The New York Times. Retrieved August 9, 2009.

- ^ Moreau, Ron; Yousafzai, Sami (August 7, 2009). "The End of Al Qaeda?". Newsweek. Retrieved August 9, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Airstrike forces Taliban to cancel meeting". UPI.com. September 9, 2009. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Suspected US drone killed up to 10 in Pakistan, Haji Mujtaba, Reuters.com, September 8.

- ^ a b Shane, Scott (December 4, 2009). "C.I.A. to Expand Use of Drones in Pakistan". The New York Times. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ "Al Qaeda Operations Planner Saleh Al-Somali Believed Dead in Drone Strike". Abcnews.go.com. December 11, 2009. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Sabloff, Nick (February 8, 2009). "Saleh al-Somali, Senior al-Qaida Member, Reportedly Killed In Drone Attack". Huffington Post. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Suspected drone attack kills 3 in Pakistan, CNN, December 31, 2009

- ^ Roggio, Bill, Long War Journal, January 7, 2010.

- ^ Gall, Carlotta (February 1, 2010). "Hakimullah Mehsud". The New York Times. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ Mazzetti, Mark; Filkins, Dexter (February 16, 2010). "Secret Joint Raid Captures Taliban's Top Commander". The New York Times. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ "Capture A Coup For U.S.-Pakistani Spy Agencies". NPR. February 16, 2010. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ a b "Capture may be turning point in Taliban fight". CNN. February 16, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ Filkins, Dexter (February 18, 2010). "In Blow to Taliban, 2 More Leaders Are Arrested". The New York Times. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ "Drone strike kills son of militant linked to Taliban, al Qaeda". CNN. February 19, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ Schmitt, Eric (May 31, 2010). "American Strike Is Said to Kill a Top Qaeda Leader". The New York Times.

- ^ [3] Archived October 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gardham, Duncan (September 28, 2010). "Terror plot against Britain thwarted by drone strike". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ Dilanian, Ken (May 2, 2011). "CIA led U.S. special forces mission against Osama bin Laden". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "Chicago Tribune: Chicago breaking news, sports, business, entertainme…". chicagotribune.com. December 3, 2012. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ^ "US forces kill Osama bin Laden in Pakistan – World news – Death of bin Laden". MSNBC. February 5, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "US forces kill Osama bin Laden in Pakistan". msnbc.com. May 2, 2011. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- ^ Gaffney, Frank J. (May 2, 2011). "GAFFNEY: Bin Laden's welcome demise". Washington Times. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "Intelligence break led to bin Laden's hide-out". Washington Times. May 2, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Schwartz, Mathew J. "Cracking Bin Laden's Hard Drives". InformationWeek. Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "Osama bin Laden dead: CIA paramilitaries and elite Navy SEAL killed Al Qaeda leader". India Times. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Osama bin Laden Killed by U.S. Forces". MSNBC. Archived from the original on May 6, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "Counterterrorism chief declares al-Qaida 'in the past'". MSNBC. February 5, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Ross, Tim (May 4, 2011). "Osama bin Laden dead: trusted courier led US special forces to hideout". London: Telegraph. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Gloria Borger, CNN Senior Political Analyst (May 20, 2011). "Debate rages about role of torture". CNN. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Mazzetti, Mark; Cooper, Helene; Baker, Peter (May 2, 2011). "Clues Gradually Led to the Location of Osama bin Laden". The New York Times.

- ^ "Pakistan rattled by news of CIA safe house in Abbottabad – World Watch". CBS News. May 6, 2011. Archived from the original on October 9, 2013. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Jaffe, Greg (September 11, 2001). "CIA spied on bin Laden from safe house". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "Pakistani Spy Chief Under Fire". The Wall Street Journal. May 7, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Charles S. Faddis, Special to CNN (May 20, 2011). "Can the U.S. trust Pakistan?". CNN. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ 05/06/2011. "Levin: Pakistan Knew Osama Bin Laden Hiding Place". ABC News. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

{{cite web}}:|author=has numeric name (help) - ^ Alexander, David (May 6, 2011). "Bin Laden death may be Afghan game-changer: Gates". Reuters. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "Clandestine Service History: Overthrow of Premier Mossadeq of Iran – November 1952-August 1953". WebCite. Archived from the original on June 9, 2009.

- ISBN 1-56004-293-1.

- ^ Mohammed Amjad. Iran: From Royal Dictatorship to Theocracy. Greenwood Press, 1989. p. 62 "the United States had decided to save the 'free world' by overthrowing the democratically elected government of Mossadegh."

- ^ "The 1953 Coup D'etat in Iran". Archived from the original on June 9, 2009. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ^ Stephen Kinzer, All the Shah's Men" An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror, John Wiley and Sons, 2003, p. 215

- ^ "Iran-U.S. Hostage Crisis (1979–1981)". Historyguy.com. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Mark Bowden (May 1, 2006). "The Desert One Debacle". The Atlantic. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- ^ "Preparing the Battlefield". The New Yorker. July 7, 2008.

- ^ "foreignpolicyjournal.com"[full citation needed]

- ^ Finn, Peter (July 22, 2010). "Retired CIA veteran will return to head clandestine service". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Live Blog – Libya". Al Jazeera. February 17, 2011. Retrieved February 23, 2011.

- ^ "News, Libya February 17th". Libyafeb17.com. Retrieved February 23, 2011.

- ^ Allen, Bennett. "C.I.A. Operatives on the Ground in Libya". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on May 28, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Levinson, Charles (April 1, 2011). "Ragtag Rebels Struggle in Battle". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "Gates: No Ground Troops in Libya on His Watch". Military.com. March 31, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Stars and Stripes (Europe Edition), April 1, 2011, "Gates: No Troops in Libya on my watch"

- ^ "Updated: Gates calls for limited role aiding Libyan rebels". The Daily Breeze. March 9, 2010. Archived from the original on April 2, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Jaffe, Greg (March 30, 2011). "In Libya, CIA is gathering intelligence on rebels". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "PressTV-CIA men, US forces entered Syria: Report".

- ^ Sanchez, Raf (September 3, 2013). "First Syria rebels armed and trained by CIA 'on way to battlefield'". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ Withnall, Adam (September 3, 2013). "Syria crisis: First CIA-trained rebel unit about to join fighting against Assad regime, says President Obama". The Independent. London.

- ^ "CIA overseeing supply of weapons to Syria rebels". The Australian. September 7, 2013.

- ^ "CIA ramping up covert training program for moderate Syrian rebels". Washington Post.

- ^ "David Ignatius: Regional spymasters make tactical changes to bolster Syrian moderates". Washington Post.

- ^ "In Syria, we finally may be fighting the way we should have in Iraq and Afghanistan". foreignpolicy.com. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ^ a b https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/02/world/middleeast/cia-syria-rebel-arm-train-trump.html

- ^ https://www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-comments/2019/the-us-withdrawal-from-syria

- ^ https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/how-trump-can-salvage-us-interests-in-syria

- ^ https://www.cnn.com/2019/10/26/politics/white-house-trump-announcement-sunday/index.html

- ^ https://www.ibtimes.com/isis-leader-al-baghdadi-dead-after-us-special-forces-raid-hideout-syria-sources-2854504

- ^ https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/us-forces-launch-operation-in-syria-targeting-isis-leader-baghdadi-officials-say/2019/10/27/081bc257-adf1-4db6-9a6a-9b820dd9e32d_story.html

- ^ https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2019/10/27/isis-leader-al-baghdadi-believed-killed-in-us-commando-raid/

- ISBN 978-1-59420-007-6.

- ^ Douglas, Waller (February 3, 2003). "The CIA Secret Army". TIME.

- ^ Shane, Scott (June 22, 2008). "Inside a 9/11 Mastermind's Interrogation". The New York Times. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ Eggen, Dan; Pincus, Walter (December 18, 2007). "FBI, CIA Debate Significance of Terror Suspect". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Bin al-Shibh to go to third country for questioning". CNN. September 17, 2002. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ Shane, Scott (June 22, 2008). "Inside a 9/11 Mastermind's Interrogation". The New York Times. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ "Top al Qaeda operative arrested". Archived from the original on August 26, 2006. Retrieved 2013-05-16. CNN, 2002-11-22

- ^ "Pakistan seizes 'al Qaeda No. 3'". CNN. May 5, 2005. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar: Afghan Top Taliban Captured, Talking To Authorities". Abcnews.go.com. February 16, 2010. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Daugherty (2004), Preface xix.

- ^ a b Risen, James; Johnston, David (December 15, 2002). "Bush Has Widened Authority of C.I.A. to Kill Terrorists". The New York Times. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ CIA Had Plan To Assassinate Qaeda Leaders, Mark Mazzetti and Shane Scott, The New York Times, July 14, 2009, p. A1.

- ^ "CIA Plan Envisioned Hit Teams Killing al Qaeda Leaders", Siobahn Gorman, The Wall Street Journal, July 14, 2009, A3

- ^ Robert Haddick. "This Week at War: Company Men". Foreign Policy. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Stein, Jeff (December 30, 2010). "SpyTalk – 2010: CIA ramps way up". Voices.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Tiku, Nitasha. "Obama's National-Security Picks Cross the Line Between Spy and Soldier – Daily Intel". New York. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Devine, Jack (July 29, 2010). "The CIA Solution for Afghanistan". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Daugherty (2004), p. xix.

- ^ China [full citation needed]

- ^ "Trump's CIA Has Set up Teams to Kill Terrorists".

- ^ https://katu.com/afternoon-live/books-authors/surprise-kill-vanish-the-secret-history-of-cia-paramilitary-armies-operators-and-assa

- ^ https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/fred-burton-author-annie-jacobsen-book-history-cia-stratfor-podcast

- ^ a b "Seven Days in the Arctic". CIA. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ a b "IACSP_MAGAZINE_V11N3A_WAUGH.indd" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 4, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ a b "CIA Remembers Employees Killed in the Line of Duty". CIA. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "William Francis (Chief) Carlson – CIA – Special Forces – Roll Of Honour". Specialforcesroh.com. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Jehl, Douglas (October 29, 2003). "Two C.I.A. Operatives Killed In an Ambush in Afghanistan". The New York Times. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

After (Chief) Carlson's death, he soon became a legend among his current peers from the same organizations. Very little has been documented, due to operational security requirements at such a high level, but what has been known by many who have studied his life was that he was possibly one of the most unique and memorable assets/operators (with SAD (SOG), as well as when in Delta, or TF Green as they were last referred to. His awards, as one former Delta operator once quietly said, were not, and would never be, worthy of his heroism in the face of an overwhelming force during the time of the ambush and the past engagements and operations he has been apart of that have become milestones in history, from Bosnia, Iraq, Afghanistan, and up to his death. Rumors later surfaced that those responsible for killing the former SEAL and Chief were dealt with rapidly, but as with so many near mythical heroes in U.S. Special Operations (especially retiring Tier 1 operators), it remains a loss for the families who luckily have had some support from the SOF community, and foundations have been established.

- ISBN 9780805447125. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ^ Safe For Democracy: The Secret Wars of the CIA, John Prados, 2006 p. 10

- ^ Safe For Democracy: The Secret Wars of the CIA, John Prados, 2006 p. xxii

- ^ William F. Buckley, Jr. (January 26, 2007), "Howard Hunt, RIP" Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tad Szulc, Compulsive Spy: The Strange Career of E. Howard Hunt (New York: Viking, 1974)

- ^ Vidal, Gore. (December 13, 1973) The Art and Arts of E. Howard Hunt. New York Review of Books

- ^ a b c d "The Stars on the Wall." Central Intelligence Agency, April 24, 2008.