Talk:Tamraparni/draft

This article possibly contains original research. (July 2019) |

Tamraparni (

Etymology

A meaning for the term following its derivation became "copper-colored leaf", from the words Thamiram (

Geography

Present day Sri Lanka, the Tan Porunai river and Indonesia

Tamraparni is the oldest historical name of the island of

The

Society and culture

Tamraparniyan royalty, economy and trade

A successful society built from strong spiritual values in governance, a lucrative Tamraparniyan economy and international trade culture ensured a reputation for the region as being a highly developed example and the richest of the

Elephants, gold, pearls and law

The eminent grammarian, mathematician and Vedic priest

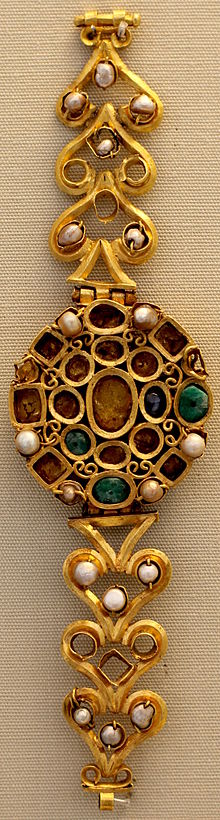

The northwest coast of Sri Lanka had an equally prospering pearl trade, overseen at Kalputti, Kudiramalai and the emporium

Valmiki's

Citing Onesicritus, Pliny states tigers and elephants on the island were hunted for sport during his time – "

Gems, ebony and spices

On Tamraparni island, Agastya's hermitage near Adam's Peak in the

French biblical scholar

Cinnamon is also mentioned in Hebrew texts.

Wootz steel, copper, wares and more gems

More features in post classical history

The early

Food, drink and medicine

Much of Tamraparniyan cuisine and medicine survives today in

Clothing attire, cosmetics and martial arts

With couture,

The classical era

Arts

Religion and spirituality

"Listen as I now recount the isle of Tamraparni below Pandya-desa and

worship Uma's consort there". Mahabharata. Volume 3. pp. 46–47, 99.

Vyasa, Mahabharata. c.401 BCE on Trincomalee Koneswaram of Tamraparni island.[43]

The culture of Tamraparni was dominated by religion. Belief in the divine was ingrained in ancient Tamraparniyan civilization from its inception, where the

Hinduism

The city of Trincomalee is uniquely a

Adam's Peak, or "Sivan Oli Pada Malai" in Tamil (Siva's One Foot Mountain) features as "Uli Pada" of the Malea mountain range on Ptolemy's Taprobana map, and features a large footprint in a shrine that Hindus believe is that of the god Shiva. In Vyasa's Mahābhārata (3:88), a Sanskrit passage on the words of Saptarishi Pulastya (Visravas and Agastya's father) relates to the island and Hindu worship at the Koneswaram temple, describing indigenous and continental pilgrims across the island, including the shrine, before the Anuradhapura period. "Listen, O son of Kunti, I shall now describe Tamraparni. In that asylum the gods had undergone penances impelled by the desire of obtaining salvation. In that region also is the lake of Gokarna, celebrated over the three worlds...".[43] This literature elaborates on the two ashrams of the Siddhar Agastya on Tamraparni island – one near Trincomalee bay (now located at Kankuveli) and another atop the Malaya mountain range (that situated near Adam's Peak).[43][313] The Dakshina Kailasa Maanmiam details one of Agastya's routes, from the Vedaranyam forests of Point Calimere to the now ruined Tirukarasai Parameswara Siva temple on the banks of the Mahaveli Ganga river, then to Koneswaram, then Ketheeswaram of Manthai to worship, before finally settling at Pothigai. The Siva-worshipping Siddhar Patanjali's birth in Trincomalee and Agastya's presence points to Yoga Sun Salutation originating on the sacred promontory of the city.[314][315][316][317] The Tamraparniyan sea route was adopted by the Siddhar alchemist Bogar in his travels from South India to China via Sri Lanka; a disciple of Agastya's teachings, Bogar himself taught meditation, alchemy, yantric designs and Kriya yoga at the Kataragama Murugan shrine in the third century CE, inscribing a yantric geometric design etched onto a metallic plate and installing it at the sanctum sanctorum of the Kataragama complex.[318][319] Punch-marked coins from 500 BCE discovered beneath a temple in Kadiramalai-Kandarodai bear the image of the deity Lakshmi.[320][321][322] The inscriptions and ruins of Kankuveli alongside Vyasa's Mahabharata reveal the umbilical relationship of Kankuveli's Agastya ashram with the Siva temple of Koneswaram and his father Pulastya, relating its high sanctity and popularity with Tamraparni's natives. In fact, the Matsya Purana describes Agastya as a native of Sri Lanka.[323]

These Hindu features were often described by their Hellenistic/Roman counterparts in early Western accounts. Pliny the Elder confirms that even by his time, inhabitants of Taprobane island worship "

A scion of one of Tamraparni's oldest

Several shrines to Agastya exist along the banks of the river Tamraparni, as does the Kubera Theertham. In Vyasa's Tambaravani Mahatmayam, the holiness of the river is shared with the Sanskrit shloka Smaraṇāt darśanāt dhyānāt snānāt pānādapi dhruvam, Karmavicchedinī sarvajantūnāṃ mokṣhadāyinī meaning "Tamraparni is the river, which destroys the

The

Buddhism and Jainism

The Buddha, according to the Mahavamsa, made three visits to Tamraparni, stopping at Nainativu and Kalyani. Both towns were strongholds of the Naga nation. On his second visit, the chronicle states he settled a dispute between the Naga kings Chulodara and Mahodara (uncle and nephew), over a gem set throne which he was then offered.

Kubera was incorporated into the Jain and Buddhist pantheons with the patronym Vaiśravaṇa (Sanskrit) / Vessavaṇa (Pali) / Vesamuni (Sinhala), meaning "Son of Vaisravas", and syncretised as one of the latter religion's Four Heavenly Kings.[20][349] In the Buddhist text Jataka-mala by Aryasura, about the Buddha's previous lives, Agastya is co-opted and included as an example of his predecessor in the seventh chapter. The Agastya-Jataka story is carved as a relief in the Ajanta Caves of Maharashtra and the Borobudur of Java, the world's largest early medieval era Mahayana Buddhist temple.[350][351] The Divyāvadāna or "Divine narratives" a Sanskrit anthology of Buddhist tales from the 2nd century, calls Sri Lanka "Tamradvipa" and gives an account of a merchant's son who met Yakkhinis, dressed like celestial nymphs (gandharva), in Sri Lanka.[20] The Valahassa Jataka relates the story of the arrival of five hundred shipwrecked merchants, from

Agastya's shrine on Pothigai Hills at Tamraparni river's source is important in the context of the Hindu Ramayana according to the Manimekhalai, which is the first Tamil literature to mention Agastya, while simultaneously conceiving and anticipating South India (Tamilakam), Sri Lanka and Java as a single Buddhist religious landscape.

"Tamraparniya" is a name given to one of the

Despite the Mahāvihāra's South Indian connection, the largest and most popular Tamraparniyan Buddhist tradition among the island's indigenous Tamils was the

A fragmentary slab inscription of Sundara Mahadevi, the queen consort of Vikramabahu I of Polonnaruwa in the 12th century, states that a great Sthaviravadin of the Sinhalese Sangha by the name of Ananda was instrumental in "purifying the order" in Tambarattha.[22] In the fifteenth century, the monk Chappada from Arimaddana city, Pagan, Myanmar came to the "island of Tambapanni", where, according to the colophon of the Sankhepavannana he authored, he purified the sasana order in Sri Lanka with the help of the king Parakramabahu VI of Kotte whom he was very dear to, in the city of Jayavardhanapura and he "caused a sima to be consecrated, according to the vinaya rules and avoiding all unlawful acts."[387] Paramatthavinicchaya's author Anuraddha, according to its colophon, was a monk born in Kanchipuram who lived during the time of writing the poem in Tanjanagara of "Tambarattha", while Buddharakkhita states in Jinalankara that Anuraddha had a high reputation among the learned men of Coliya-Tambarattha.[22]

Other mentions

Old writers often speak of the

The Greek name was adopted in medieval Irish (

The name remained in use in early modern Europe, alongside the Persianate Serendip, with Traprobana mentioned in the first strophe of the

References

- ^ ISBN 9788175741898.

- ^ a b c K. Sivasubramaniam – 2009. Fisheries in Sri Lanka: anthropological and biological aspects, Volume 1. "It is considered most probable that the name was borrowed by the Greeks, from the Tamil 'Tamraparni' for which the Pali...to Ceylon, by the Tamil immigrants from Tinnelvely district through which ran the river called to this date, Tamaravarani"

- ISBN 9789385563164. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d Leelananda Prematilleka, Sudharshan Seneviatne – 1990: Perspectives in archaeology: "The names Tambapanni and Tamra- parni are in fact the Prakrit and Sanskrit rendering of Tamil Tan porunai"

- ^ a b John R. Marr – 1985 The Eight Anthologies: A Study in Early Tamil Literature. Ettukai. Institute of Asian Studies

- ^ The Maha Bodhi (1983) – Volume 91 – Page 16

- ^ Sakti Kali Basu (2004). Development of Iconography in Pre-Gupta Vaṅga – Page 31

- ^ Caldwell, Robert (1856). A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian Or South-Indian Family of Languages. Bavaria: Harrison. pp. 80–83.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Caldwellwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ The Indian Geographical Journal, Volume 15, 1940 p345

- ^ a b c Iravatham Mahadevan (2003), EARLY TAMIL EPIGRAPHY, Volume 62. pp. 169

- ^ a b c Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta Sastri (1963) Development of Religion in South India – Page 15

- ^ a b Layne Ross Little (2006) Bowl Full of Sky: Story-making and the Many Lives of the Siddha Bhōgar pp. 28

- ^ Ameresh Datta. Sahitya Akademi, 1987 – Indic literature. Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: A-Devo. pp 115

- ISBN 81-206-0209-9.

- ^ Mondal, Sambhu Nath (2006). Decipherment of the Indus-Brâhmî Inscriptions of Chandraketugarh (Gangâhrada)--the Mohenjodaro of East India. University of Michigan: Shankar Prasad Saha. pp. 32–51. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ Rapson, Edward James; Haig, Sir Wolseley; Burn, Sir Richard; Dodwell, Henry (1922). The Cambridge History of India: Ancient India, edited by E. J. Rapson. University Press. p. 424. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ Suryavanshi, Bhagwan Singh (1986). Geography of the Mahabharata. Ramanand Vidya Bhawan. p. 44. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ Sircar, D. C. (1967). Cosmography and Geography in Early Indian Literature. Indian Studies: Past & Present. p. 55. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ ISBN 81-206-0209-9. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- ^ Simpson, William (1874). Meeting The Sun a Journey All Round the World Through Egypt, China, Japan, and California by William Simpson. Longmans, Green, Reader and Dyer. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ a b c W. M. Sirisena (1978). Sri Lanka and South-East Asia: Political, Religious and Cultural Relations from A.D. C. 1000 to C. 1500 pp. 89

- ^ Bochart, Samuel (1712). Samuelis Bocharti opera omnia. Hoc est Phaleg, Chanaan, et Hierozoicon. Quibus accesserunt dissertationes variae (etc.) (in Latin). apud Cornelium Boutesteyn & Samuelem Luchtmans. p. 692. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ Estienne, Charles (1686). Dictionarium historicum, geographicum, poeticum: gentium, hominum, deorum gentilium ... Opus admodum utile & apprime necessarium a Carolo Stephano inchoatum. Ad incudem verò revocatum innumerisque penè locis auctum & emaculatum per Nicolaum LLoydium ... cui accessit index geographicus . (in Latin). impensis B. Tooke, T. Passenger, T. Sawbridge, A. Swalle & A. Churchill. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ "Astrological Magazine". Astrological Magazine. 56 (1–6): 75. 1967. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ Robert Knox. 1651. An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon in the East-Indies. – London. p167

- ISBN 8171418767. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ISBN 9783639304534.

- ^ The Maha Bodhi (1983) - Volume 91 - Page 16

- ^ Sakti Kali Basu (2004). Development of Iconography in Pre-Gupta Vaṅga - Page 31

- ^ Caldwell, Robert (1856). A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian Or South-Indian Family of Languages. Bavaria: Harrison. pp. 80–83.

- ^ Seneviratne, Sudharshan. "Reading the past in a more inclusive way". frontline.thehindu.com. Frontline. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ de Silva, A. History of Sri Lanka, p. 129

- ^ Indrapala, K. The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, p. 91

- ^ Mativāṇan̲, Irāman̲; Mahalingam, N.; Civilization, International Society for the Investigation of Ancient (1995). Indus script among Dravidian speakers. International Society for the Investigation of Ancient Civilizations. p. 52. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ Pridham, Charles (1849). An Historical, Political, and Statistical Account of Ceylon and Its Dependencies. T. and W. Boone. p. 7. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Frawley, David (1993). Gods, Sages and Kings: Vedic Secrets of Ancient Civilization. New Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass.

- ^ Elder, Pliny the (2015). Delphi Complete Works of Pliny the Elder (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ Ghurye, Govind Sadashiv (1977). Indian acculturation: Agastya and Skanda. University of California: Popular Prakashan. p. 38. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ISBN 9789004185661. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ Sambhu Nath Mondal. 2006. Decipherment of the Indus-Brâhmî Inscriptions of Chandraketugarh (Gangâhrada)--the Mohenjodaro of East India. pp28 Sanskritization : "yojanani setuvandhat arddhasatah dvipa tamraparni"

- ^ Romesh Chunder Dutt (2002). The Ramayana and the Mahabharata Condensed Into English Verse. p99

- ^ a b c d e Vyasa. (400 BCE). Mahabharata. Sections LXXXV and LXXXVIII. Book 3. pp. 46–47, 99

- ^ C. Rasanayagam, Mudaliyar C. Rasanayagam. (1993). Ancient Jaffna: Being a Research Into the History of Jaffna from Very Early Times to the Portug[u]ese Period. Asian Educational Services. pp. 103–105

- ^ "Rivers of Western Ghats – Origin of Tamiraparani". Centre for Ecological Sciences. Indian Institute of Science. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ISBN 9780520063532. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781400856923. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar. (1995) The Purana Index. pp. 16

- ^ The Madras journal of literature and science, Volume 1. Bavarian State Library. 1838. pp. 278–279.

- ^ N. Subrahmanian – 1994. Original sources for the history of Tamilnad: from the beginning to c. A.D. 600

- ISBN 9788120812185. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781135590949.

- ^ Jyotirmay Sen. "Asoka's mission to Ceylon and some connected problems". The Indian Historical Quarterly. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- ^ a b c Asian Educational Services (1994). A General Description of the Island, Historical, Physical, Statistical pp. 14–16

- ^ Suckling, Horatio John (1876). Ceylon: A General Description of the Island, Historical, Physical, Statistical. Containing the Most Recent Information, Volume 1 (1 ed.). New York: Chapman & Hall. pp. 13–22.

- ^ Pridham, Charles (1849). An Historical, Political, and Statistical Account of Ceylon and Its Dependencies. T. and W. Boone. p. 7. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ W. J. Van Der Meulen, Suvarnadvipa and the Chryse Chersonesos, Indonesia, Vol. 18, 1974, page 6.

- ISBN 962-593-470-7.

- ^ Sudhakar Chattopadhyaya – 1980. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea & Ptolemy on Ancient Geography of India

- ^ Pondicherry Institute of Linguistics and Culture, 1994. PILC Journal of Dravidic Studies: PJDS., Volume 4

- ^ Suckling, Horatio John (1876). Ceylon: A General Description of the Island, Historical, Physical, Statistical. Containing the Most Recent Information, Volume 1 (1 ed.). New York: Chapman & Hall. pp. 13–22.

- ^ Suckling, Horatio John (1876). Ceylon: A General Description of the Island, Historical, Physical, Statistical. Containing the Most Recent Information, Volume 1 (1 ed.). New York: Chapman & Hall. pp. 13–22.

- ^ Ramananda Chatterjee – 1930. The Modern Review – Volume 47 – Page 96

- ^ Ponnambalam Arunachalam, Sir Ponnambalam Arunachalam – 2004. Sketches of Ceylon History. pp. 33

- ^ a b Kurukshetra, Volume 4. Sri Lak-Indo Study Group, 1978 pp.68–70

- ^ a b Ranjan Chinthaka Mendis. Lakshmi Mendis, 1 Jan 1999. The Story of Anuradhapura: Capital City of Sri Lanka from 377 BC – 1017 Ad pp. 33

- ISBN 9780195638677. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ISBN 9789552087509. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ Prematilleka, Leelananda; Seneviatne, Sudharshan (1990). Perspectives in archaeology: Leelananda Prematilleke Festschrift, 1990. Dept. of Archaeology, University of Peradeniya. p. 89. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ISBN 9781476607481. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780521011099. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ISSN 1474-0540. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ISBN 9780521011099. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ Prematilleka, Leelananda; Seneviatne, Sudharshan (1990). Perspectives in archaeology: Leelananda Prematilleke Festschrift, 1990. Dept. of Archaeology, University of Peradeniya. p. 89. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ Suckling, Horatio John (1876). Ceylon: A General Description of the Island, Historical, Physical, Statistical. Containing the Most Recent Information, Volume 1 (1 ed.). New York: Chapman & Hall. pp. 13–22.

- ^ Ponnambalam Arunachalam, Sir Ponnambalam Arunachalam – 2004. Sketches of Ceylon History. pp. 33

- ISBN 978-90-5410-155-0.

- ^ Arunachalam, M. (1981). Aintām Ulakat Tamiḻ Mānāṭu-Karuttaraṅku Āyvuk Kaṭṭuraikaḷ. International Association of Tamil Research. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ Arokiaswamy, Celine W. M. (2000). Tamil influences in Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines. s.n. p. 25. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780774807593. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Sivaganesan, S. K. "வரலாற்று முக்கியத்துவம் வாய்ந்த வெல்லாவெளிப் பிராமிச் சாசனங்கள் ! கட்டாயம் தெரிந்துகொள்ளவேண்டியவை | Battinews.com". Battinews.com. Battinews Ltd. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ISBN 8171418767. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ "SRI TAMRAPARNI MAHATMYAM". www.kamakoti.org. Kamakoti. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ N. Subrahmanian – 1994. Original sources for the history of Tamilnad: from the beginning to c. A.D. 600

- ^ Indian Culture: Journal of the Indian Research Institute. University of Virginia: I.B. Corporation. 1984. pp. 254–255. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Banerjee, Manabendu (2000). Occasional Essays on Arthaśāstra. University of Michigan: Sanskrit Pustak Bhandar. p. 193. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Ajay Mitra Shastri, Varāhamihira (1996). Ancient Indian Heritage, Varahamihira's India: Economy, astrology, fine arts, and literature. Aryan Books International.

- ^ B, A. "The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century". sourcebooks.fordham.edu. Fordham University. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ Jyotirmay Sen. "Asoka's mission to Ceylon and some connected problems". The Indian Historical Quarterly. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- ^ Sudhakar Chattopadhyaya – 1980. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea & Ptolemy on Ancient Geography of India

- ^ Pondicherry Institute of Linguistics and Culture, 1994. PILC Journal of Dravidic Studies: PJDS., Volume 4

- ISBN 9781605204918. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Govind Sadashiv Ghurye. Caste and Race in India. p357

- ^ Chakladar, Haran Chandra (1963). The Geography of Kalidasa. Indian studies past and present. p. 47. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ^ Gopal, Ram (1984). Kalidasa: His Art and Culture. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 60–61. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781538106860.

- ^ "The Sinhalese of Ceylon and The Aryan Theory". Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ M. D. Raghavan (1971). Tamil culture in Ceylon: a general introduction. Kalai Nilayam. pp. 60

- ^ C. Sivaratnam – 1964. An outline of the cultural history and principles of Hinduism. pp. 276

- ISBN 9788120601611.

- ISBN 9788120601611.

- ^ Sambhu Nath Mondal. 2006. Decipherment of the Indus-Brâhmî Inscriptions of Chandraketugarh (Gangâhrada)--the Mohenjodaro of East India. pp28 vijayasihasa bivaha sihaurata tambapaniah yakkhini kubanna,a" Sanskritized as "vijayasirihasya vivaha sirihapuratah tamraparnyah yaksinf kubarjuaaya"

- ISBN 978-955-9140-31-3.

- ISBN 9788120830219. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ISBN 9788120830219. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ISBN 9788120611351. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ISBN 9788188237029. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ISBN 9789387456129. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ Shrikumar, A. (2 July 2014). "The trees of Madurai". The Hindu. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ISBN 9788120602083. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781402083716. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ISBN 0-8133-8845-7.

- ^ R, Valmiki. "Sree Yoga Vasishtha Maha Ramayana ( Bulusu Venkateswarulu) vols I-VI". Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ISBN 9789814785853. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ Khan, Stephen. "World's oldest clove? Here's what our find in Sri Lanka says about the early spice trade". The Conversation. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ Colburn, H (1830). The London Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, Etc. H. Colburn. p. 434. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Tennent, James Emerson (1860). Ceylon, an Account of the Island, Physical, Historical, and Topographical with Notices of Its Natural History, Antiquities and Productions. Longman. p. 539. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ISBN 0141913320.

- ^ Wright, Arnold (1999). Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon: Its History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources. Asian Educational Services. p. 16.

- ^ A, Aelian. "Aelian : On Animals, 16". www.attalus.org. Attalus.org. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Pridham, Charles (1849). An Historical, Political, and Statistical Account of Ceylon and Its Dependencies. T. and W. Boone. pp. 5–7. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Pridham, Charles (1849). An Historical, Political, and Statistical Account of Ceylon and Its Dependencies. T. and W. Boone. pp. 5–7. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Knighton, William (1845). The History of Ceylon from the Earliest Period to the Present Time: With an Appendix, Containing an Account of Its Present Condition. Longman, Brown, Green & Longmans. p. 212. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Modern Sri Lanka Studies. University of Peradeniya. 1989. p. 48. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780190625962. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ISBN 1139446169.

- ^ Suckling, Horatio John (1876). Ceylon: A General Description of the Island, Historical, Physical, Statistical. Containing the Most Recent Information, Volume 1 (1 ed.). New York: Chapman & Hall. pp. 13–22.

- ISBN 9780295807089. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ^ AS, Senthil Kumar (2017). AN ETYMOLOGICAL DICTIONARY OF TAMIL LOANWORDS IN ENGLISH, HINDI, SANSKRIT, GREEK, MINOAN AND CYPRO-MINOAN LANGUAGES. senthil kumar a s. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ^ Karanth, R. V. (2000). Gems and Gem Industry in India. Geological Society of India. p. 9. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ISBN 9789559631835. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780520303386. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781931745291. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ S. Krishnarajah (2004). University of Jaffna

- ^ Richard Leslie Brohier (1934). Ancient irrigation works in Ceylon, Volumes 1–3

- ^ Steven E. Sidebotham. Berenike and the Ancient Maritime Spice Route. pp. 75

- ISBN 978-0-9645097-6-4.

- ISBN 9780275993047. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ^ Crowningshield, Robert (Spring 2010). "Padparadscha: What's in a Name?". Gems & Gemology. 19 (1). Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Balfour, Edward (1871). Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, Commercial, Industrial and Scientific: Products of the Mineral, Vegetable and Animal Kingdoms, Useful Arts and Manufactures. Printed at the Scottish & Adelphi presses. p. 283. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ISBN 9780393239799. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Fernando, L. J. D. (1964). Bulletin. University of California: Sri Lanka Geographical Society. p. 45. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ "Organiser". Bharat Prakashan. 44. Bharat Prakashan.: 17 August 1992. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ISBN 9788120604513. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ISBN 0275993043.

- ^ Richard Leslie Brohier (1934). Ancient irrigation works in Ceylon, Volumes 1–3. pp.36

- ^ A dictionary of the Bible by Sir William Smith published in 1863 notes how the Hebrew word for peacock is Thukki, derived from the Classical Tamil for peacock Thogkai: Ramaswami, Sastri, The Tamils and their culture, Annamalai University, 1967, pp.16, Gregory, James, Tamil lexicography, M. Niemeyer, 1991, pp.10, Fernandes, Edna, The last Jews of Kerala, Portobello, 2008, pp.98, Smith, William, A dictionary of the Bible, Hurd and Houghton, 1863 (1870), pp.1441

- ^ Horatio, John Suckling (1994). "Ceylon: A General Description of the Island, Historical, Physical, Statistical". Asian Educational Services. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ Tambi-Piḷḷai Isaac Tambyah. Psalms of a Saiva Saint. Introduction. pp. 3–4

- ^ V. Kanakasabhai. The Tamils Eighteen Hundred Years Ago. pp.110

- ^ C. Rasanayagam. (1993). Ancient Jaffna: being a research into the history of Jaffna from very early times to the Portug[u]ese period. pp.87–92, 172

- ^ Manansala, Paul (1994). The Naga race. University of Michigan: Firma KLM. p. 89, 95. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ Kuppuswamy (Prof.), T. V.; Kulkarni, Shripad Dattatraya; India), Shri Bhagavan Vedavyasa Itihasa Samshodhana Mandira (Bombay (1995). History of Tamilakam. Darkness at horizon. Shri Bhagavan Vedavyasa Itihasa Samshodhana Mandira. p. 71. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ISBN 9788170241881. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ Brahmavidyā: The Adyar Library Bulletin. Adyar Library and Research Centre. 1947. p. 40. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ Stavig, Gopal (1989–1992). "Historical Contacts Between India and Egypt Before 300 A.D" (PDF). Journal of Indian History: 1–22. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ISBN 9786027244931. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Ragupathy, Ponnampalam (1987). Early Settlements in Jaffna: An Archaeological Survey. University of Michigan: Thillimalar Ragupathy. p. 67. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ Uragoda, C. G. (1987). A history of medicine in Sri Lanka from the earliest times to 1948. Sri Lanka Medical Association. p. 8. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ISBN 9780521376952. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- . Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ Balfour, Edward (1862). The Timber Trees, Timber and Fancy Woods: As Also the Forests of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia. pp. 141–142. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ Smith, William (1872). A Dictionary of the Bible: Comprising Its Antiquities, Biography, Geography and Natural History with Numerous Illustrations and Maps. N. Tibbals & Son. p. 157. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780521452571. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780486144948. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ISBN 9789004035140. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780918804549. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781134095803. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Manansala, Paul (1994). The Naga race. University of Michigan: Firma KLM. p. 89. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Heras, Henry (1953). Studies in Proto-indo-mediterranean Culture: By H. Heras. Indian Historical Research Institute. p. 345. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ISBN 9786027244955. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ Stavig, Gopal (1989–1992). "Historical Contacts Between India and Egypt Before 300 A.D" (PDF). Journal of Indian History: 1–22. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Bhandarkar, Oriental Research Institute (2000). Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Poona. University of Virginia: The Institute. p. 86. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ Pethiyagoda, Rohan (2007). Pearls, Spices, and Green Gold: An Illustrated History of Biodiversity Exploration in Sri Lanka. WHT Publications. p. 15. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ISBN 9781577310693. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ISBN 1137364599.

- ^ Suckling, Horatio John (1876). Ceylon: A General Description of the Island, Historical, Physical, Statistical. Containing the Most Recent Information, Volume 1 (1 ed.). New York: Chapman & Hall. p. 271.

- ISBN 9780203590874. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ Matthew, Samuel; Joy, P. P.; J, Thomas (Feb 1998). "Cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum Presl.) for flavour and fragrance". PAFAI Journal. 20 (2): 37–42. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ISBN 9788120601178. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780203590874. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- )

- ISBN 9780521689434. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ Smith, William (1870). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Little. p. 1092. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ Pethiyagoda, Rohan (2007). Pearls, Spices, and Green Gold: An Illustrated History of Biodiversity Exploration in Sri Lanka. WHT Publications. p. 15. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ Nichols, John (1802). The Gentleman's Magazine. University of California: E. Cave. p. 1008. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ISBN 9789519380353. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781420023367. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781439147955. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ISBN 9780851996059. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ISBN 9780123918659. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ Khan, Stephen. "World's oldest clove? Here's what our find in Sri Lanka says about the early spice trade". The Conversation. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ISBN 9780299126407. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ISBN 9789057890529. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ ISBN 9789155453572.

- ^ "Post-Conflict Archaeology of the Jaffna Peninsula – Durham University". www.dur.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-12-06.

- ^ Ceylon Journal of Medical Science. University of California. 1949. p. 58.

- ^ (Begley,V. 1973)

- ISBN 9780521376952.

- ISBN 9788180900037.

- ISBN 9780646425467.

- ^ International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics. Department of Linguistics, University of Kerala. 2009. p. 62.

- ^ Thiagarajah, Dr. Siva. "The people and cultures of prehistoric Sri Lanka – Part Three". SriLankaGuardian.org. Sri Lanka Guardian. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Pillay, Kolappa Pillay Kanakasabhapathi (1963). South India and Ceylon. University of Madras. p. 117.

- ^ Torntore, Susan Joyce (2002). Italian Coral Beads: Characterizing Their Value and Role in Global Trade and Cross-cultural Exchange. University of Minnesota. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780299126407. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781440835513. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Staffordshire Hoard Festival 2019". The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ "A trail of garnet and gold: Sri Lanka to Anglo-Saxon England". The Historical Association. 22 June 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ "Acquisitions of the month: June 2018". Apollo Magazine. 5 July 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780520300927. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ Rotunda (22 ed.). Royal Ontario Museum. 1989. p. 25. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ Jarus, Owen; May 13, Live Science Contributor; ET, Live Science Contributor. "Gold Treasures Discovered in Ming Dynasty Tomb (Photos)". Live Science. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

{{cite web}}:|first2=has generic name (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=and|2=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ISBN 9780964399327. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ Minerals Yearbook. Bureau of Mines. 1984. p. 1034. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ISBN 9789559159001. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ISBN 9783823612896. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ISBN 9783805325127. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781945926334. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ "Godavaya Ancient Shipwreck Excavation". Institute of Nautical Archaeology. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ Gannon, Megan; February 4, News Editor; ET, News Editor. "Indian Ocean's Oldest Shipwreck Set for Excavation". Live Science. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

{{cite web}}:|first2=has generic name (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=and|2=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ISBN 9781351997515.

- ^ ISBN 2-85539-630-1.).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link - ^ "GEMMOLOGICAL PROFILE" (PDF). Gubelingemlab. Gubelin. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ^ Proceedings. University of Michigan: Organising Committee XXVI International Congress of Orientalists. 1969. pp. 224–226. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Karuṇāniti, Kalaiñar Mu (1968). Tale of the Anklet. Tamizhkani Pathippagam. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Publications – Folklore Society (36 ed.). UK: University of Michigan. 1895. p. 180. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780226616025. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ "The ancient departure port on maritime Silk Road". kaogu.cssn.cn. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780750610070. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780871692245. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ^ Mcrindle, John Watson (1901). Ancient India as described in classical literature. Westminster Constable. p. 160.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ci Patmanātan, S. Pathmanathan (1978). The Kingdom of Jaffna, Volume 1. pp. 237

- )

- ^ Sastri, Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta (1978). South India and South-East Asia: studies in their history and culture. Geetha Book House. p. 255. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ISBN 0275993043.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

autogenerated1985was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Battuta Ibn. Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325–1354. p. 260. Also spelt "Dinaur" (anglicized spelling) in other sources.

- ISBN 9788126902866. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ Iyer, Krishna; Nanjundayya, Hebbalalu Velpanuru (1935). The Mysore tribes and castes. University of Mysore. p. 476.

- ^ Pillay, Kolappa Pillay Kanakasabhapathi (1963). South India and Ceylon. University of Madras. p. 39. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ Nākacāmi, Irāmaccantiran̲ (1995). Roman Karur: a peep into Tamils' past. Brahad Prakashan. pp. 14–15. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ISBN 9780971395602. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ Journal of Kerala Studies. University of Kerala. 2011. p. 59. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ Journal of Kerala Studies. University of Kerala. 2011. p. 59. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ Pillay, Kolappa Pillay Kanakasabhapathi (1963). South India and Ceylon. University of Madras. p. 33.

- ^ Navaratnam, C. S. (1964). A Short History of Hinduism in Ceylon: And Three Essays on the Tamils. University of California: Sri Sammuganatha Press. p. 86.

- ^ Levers, R. W. (1899). Manual of the North-Central Province, Ceylon. Minnesota: G.J.A. Skeen.

- ^ Tolkāppiyar, P. S. Subrahmanya Sastri. (1945). Tolkāppiyam-Collatikāram. pp. 30

- ^ Knighton, William (1845). The History of Ceylon from the Earliest Period to the Present Time: With an Appendix, Containing an Account of Its Present Condition. Longman, Brown, Green & Longmans. p. 212. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780521232104.

- ^ Devasia, T. K. "Who should get the tonnes of gold lying in the world's richest temple: Kerala, Modi or Pakistan?". Scroll.in. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ "Gold treasure at India temple could be the largest in the world". COMMODITYONLINE.

- ^ "India to evaluate world's largest gold treasure soon". Archived from the original on 2015-04-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Asia Times Online :: India's temple treasure prompts test of faith".

- ^ R. Krishnakumar (16 July 2011). "Treasures of history". Frontline. 28 (15). Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ISBN 9781351723404. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ISBN 9788185790411. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ Academy, Himalayan. "Hinduism Today Magazine". www.hinduismtoday.com. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ Khan, Stephen. "World's oldest clove? Here's what our find in Sri Lanka says about the early spice trade". The Conversation. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ Knighton, William (1845). The History of Ceylon from the Earliest Period to the Present Time: With an Appendix, Containing an Account of Its Present Condition. Longman, Brown, Green & Longmans. p. 209. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ A, Aelian. "Aelian : On Animals, 16". www.attalus.org. Attalus.org. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Knighton, William (1845). The History of Ceylon from the Earliest Period to the Present Time: With an Appendix, Containing an Account of Its Present Condition. Longman, Brown, Green & Longmans. p. 212. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Purchas, Samuel (1625). Purchas his pilgrimes. W. Stansby for H. Fetherstone. p. 89. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Silva, K. M. De; Peradeniya, University of Ceylon (1959). History of Ceylon. Ceylon University Press. p. 18. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781848857858. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ISBN 9789022009871. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Cuppiramaṇiyan̲, Ca Vē; Mātavan̲, Vē Irā; Studies, International Institute of Tamil (1983). Heritage of the Tamils: Siddha medicine. International Institute of Tamil Studies. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Burton, Sir Richard Francis (1884). The Book of the Sword. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 111.

- ISBN 9781108026840. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Balfour, Edward (1862). The Timber Trees, Timber and Fancy Woods: As Also the Forests of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia. pp. 141–142. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ Pillai, Kanapathi. "Tamil Publications in Ceylon" (PDF). Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780521445498. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Purchas, Samuel (1625). Purchas his pilgrimes. W. Stansby for H. Fetherstone. p. 89. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Pridham, Charles (1849). An Historical, Political, and Statistical Account of Ceylon and Its Dependencies. T. and W. Boone. p. 8. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Kirīmē Amātyāṃśaya, Sălasum Kriyātmaka (1986). "Nava Saṃskṛti". Ministry of Plan Implementation. 1 (1). Ministry of Plan Implementation: 41. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ISBN 9788185163871. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Kirīmē Amātyāṃśaya, Sălasum Kriyātmaka (1986). "Nava Saṃskṛti". Ministry of Plan Implementation. 1 (1). Ministry of Plan Implementation: 41. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Pridham, Charles (1849). An Historical, Political, and Statistical Account of Ceylon and Its Dependencies. T. and W. Boone. p. 9. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Uragoda, C. G. (1987). A history of medicine in Sri Lanka from the earliest times to 1948. Sri Lanka Medical Association. p. 8. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780646425467.

- ^ International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics. Department of Linguistics, University of Kerala. 2009. p. 62.

- ISBN 9780805499353. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780313316104. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781405337502. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781405337502. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ a b Edward Balfour. (1873). Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, Commercial, Industrial and Scientific: Products of the Mineral, Vegetable and Animal Kingdoms, Useful Arts and Manufactures, Volume 5. Scottish & Adelphi presses. pp. 260

- ^ M. S. Purnalingam Pillai. Sundeep Prakashan, 1996. Ravana The Great : King of Lanka – Page 84

- ^ C. Rasanayagam, Mudaliyar C. Rasanayagam. (1993) Ancient Jaffna: Being a Research Into the History of Jaffna from Very Early Times to the Portuguese Period. pp385

- ISBN 9781421404301.

- ^ Pillai, Kanapathi. "Tamil Publications in Ceylon" (PDF). Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781317991144. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781847653963. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ Sivathamby, K. "The Ritualistic Origins of Tamil Drama". tamilnation.co. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ISBN 9780190912031. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781317013327. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ Journal of the Institute of Asian Studies. The Institute. 2001. pp. 112–117. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ISSN 0195-6167. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ISBN 9788185163253. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ Forbes, Jonathan; Turnour, George (1840). Eleven Years in Ceylon: Comprising Sketches of the Field Sports and Natural History of that Colony, and an Account of Its History and Antiquities. R. Bentley. pp. 43–44. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ISBN 9789385563959. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ISBN 9789559631835. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ISBN 9780646365701. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ISBN 9780760728550. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ISBN 9788124601624. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ Frawley, David (1993). Gods, Sages and Kings: Vedic Secrets of Ancient Civilization. New Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass.

- ^ Elder, Pliny the (2015). Delphi Complete Works of Pliny the Elder (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781680371338. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ Jayaprakash, Author Velu (7 June 2014). "Why Swarna Prashana on Pushya nakshatra?". Swarna Prashana. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

{{cite web}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - ISBN 9789350572504. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781934145272. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ISBN 9789558733974. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ Academy, Himalayan. "Hinduism Today Magazine". www.hinduismtoday.com. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ S. Vithiananthan (1980). Nān̲kāvatu An̲aittulakat Tamil̲ārāycci Makānāṭṭu nikal̲ccikaḷ, Yāl̲ppāṇam, Can̲avari, 1974, Volume 2. pp. 170

- OCLC 8305376.

The Dakshina Kailasa Manmiam, a chronicle on the history of the temple, notes that the Sage Agastya proceeded from Vetharaniam in South India to the Parameswara Shiva temple at Tirukarasai — now in ruins — on the bank of the Mavilli Gangai before worshipping at Koneswaram; from there he went to Maha Tuvaddapuri to worship Lord Ketheeswarar and finally settled down on the Podiya Hills

- ISBN 955-9429-91-4.

Of particular importance are the references in two Sanskrit dramas of the 9th century to the abode of Agastya shrines on Sivan Oli Padam Malai called Akastiya Stapanam, Trikutakiri and Ilankaitturai in the Trincomalee District where Koneswaram is located

- ^ "Kriya Babaji and Kataragama". kataragama.org. Kataragama.org. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780226149349. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ Nākacāmi, Irāmaccantiran̲ (1995). Roman Karur: a peep into Tamils' past. Brahad Prakashan. p. 37-38. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780646425467.

- ^ International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics. Department of Linguistics, University of Kerala. 2009. p. 62.

- )

- ^ Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography: Iabadius-Zymethus (Greek Geography ed.). Oxford University: Walton & Maberly. 1857. p. 395.

- ^ Harrigan, Patrick; Samuel, G. John (1998). Kataragama, the Mystery Shrine. Institute of Asian Studies. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ In a 12th-century commentary on lines 593 and 594 of Orbis descriptio, Eustathius of Thessalonica describes the temple as the Coliadis Veneris Templum, Taprobana – Eustathius (archevêque de Thessalonique) Commentarii in Dionysium Periegetam. pp. 327–329

- ^ Dionysius Periegetes. Dionysii Orbis terrae descriptio. pp.153–154 – Dionysius Periegetes also describes the Chola promontory to Venus of Taprobana as being a promontory to the extreme of the Ganges river of Ceylon (the Mavilli Gangai), served by the ocean below.

- ^ Indicopleustes, Cosmas (1897). "A description of Indian Animals, and of the Island of Taprobane". Christian Topography. Book XI: 358–373.

- ^ Mcrindle, John Watson (1901). Ancient India as described in classical literature. Westminster Constable. p. 160.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - )

- ^ "Seated Agastya". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Samuel Eilenberg Collection, Gift of Samuel Eilenberg, 1987. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ Upendra Thakur (1986). Some Aspects of Asian History and Culture. pp. 42

- ^ Deraniyagala, S.U. (2003) THE URBAN PHENOMENON IN SOUTH ASIA: A SRI LANKAN PERSPECTIVE. Urban Landscape Dynamics – symposium. Uppsala universitet

- ^ Deraniyagala 1992:709-29; Karunaratne and Adikari 1994:58; Mogren 1994:39; with the Anuradhapura dating corroborated by Coningham 1999)

- ^ Hopkins 1915, pp. 142–3

- ^ Wikramagamage, Chandra (1998). Entrances to the Ancient Buildings in Sri Lanka. Academy of Sri Lankan Culture. p. 25. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- ^ Ranganathan, S. (1999). Megha-dutam and Shri Hamsa Sandeshah: A Parallel Study. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 48. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- ^ The Madras journal of literature and science, Volume 1. Bavarian State Library. 1838. pp. 278–279.

- ^ Bertold Spuler. (1975) Handbook of Oriental Studies, Part 2 pp. 63

- ^ K. D. Swaminathan, CBH Publications, 1990 – Architecture. South Indian temple architecture: study of Tiruvāliśvaram inscriptions. pp. 67–68

- ^ Epigraphia Indica – Volume 24 – Page 171 (1984)

- ^ Niharranjan Ray, Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya – 2000. A Sourcebook of Indian Civilization – Page 484

- ^ R. Tirumalai, Tamil Nadu (India). Dept. of Archaeology (2003). The Pandyan Townships: The Pandyan townships, their organisation and functioning

- ^ "YogaEsoteric :: Swami Sivananda ::". www.yogaesoteric.net. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ Ontological and Morphological Concepts of Lord Sri Chaitanya and His Mission, Volume 1. Bhakti Prajnan Yati Maharaj, Chaitanya, Bhakti Vilās Tīrtha Goswāmi Maharāj Sree Gaudiya Math, 1994. pp. 248

- ISBN 9788120610712. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ The Daṭhávansa, Or, The History of the Tooth-relic of Gotama Buddha. Trübner & Company. 1874. pp. 33–34. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Sri Nandan Prasad, Historical Perspectives of Warfare in India: Some Morale and Matériel Determinants, Project of History of Indian Science, Philosophy, and Culture – 2002

- ISBN 81-7936-009-1.

- )

- ISBN 978-90-5410-155-0.

- ^ Raj Kumar (2003). Essays on Ancient India. pp. 251

- ISBN 9788190815703. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ^ Anne E. Monius Oxford University Press, 6 Dec 2001. Imagining a Place for Buddhism: Literary Culture and Religious Community in Tamil-Speaking South India. pp. 114

- ^ G. Kamalakar, M. Veerender, Birla Archaeological & Cultural Research Institute Sharada Pub. House, 1 Jan 2005. Buddhism: art, architecture, literature & philosophy, Volume 1

- ^ Kisan World, Volume 21. Sakthi Sugars, Limited, 1994. pp. 41

- ^ Shu Hikosaka (1989). Buddhism in Tamilnadu: A New Perspective – Page 187

- ^ Tamil Culture, Volume 2–3. University of California: Tamil Literature Society, Academy of Tamil Culture. 1953. p. 188.

- ^ Navaratnam, C. S. (1964). A Short History of Hinduism in Ceylon: And Three Essays on the Tamils. Sri Sammuganatha Press. p. 7.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ISBN 9782855396262.

- ^ figure, Collection Online, British Museum, retrieved 9 December 2013

- ^ a b Śrīdhara Tripāṭhī. 2008. Encyclopaedia of Pali Literature: The Pali canon – Page 79

- ^ Debarchana Sarkar Sanskrit Pustak Bhandar, 2003. Geography of ancient India in Buddhist literature. pp. 309

- ^ Nalinaksha Dutt. Buddhist Sects in India. p 212

- ^ Hari Kishore Prasad – 1970. The Political & Socio-religious Condition of Bihar, 185 B.C. to 319 A.D. pp.230

- ^ The Maha Bodhi (1983) – Volume 91 – Page 16

- ^ Sakti Kali Basu (2004). Development of Iconography in Pre-Gupta Vaṅga – Page 31

- ^ a b Parmanand Gupta (1989). Geography from Ancient Indian Coins & Seals. p183

- ^ a b Indian History Congress. 1973. Proceedings – Indian History Congress – Volume 1 – Page 46.

- ^ Es Vaiyāpurip Piḷḷai. Vaiyapuripillai's History of Tamil Language and Literature: From the Beginning to 1000 A.D. New Century Book House, 1988. pp 30

- ^ A. Aiyappan, P. R. Srinivasan. (1960). Story of Buddhism with Special Reference to South India. pp.55

- ^ G. John Samuel, Ār. Es Śivagaṇēśamūrti, M. S. Nagarajan – 1998. Buddhism in Tamil Nadu: Collected Papers – Page xiii

- ^ Anne E. Monius, Oxford University Press, 6 Dec 2001. Imagining a Place for Buddhism: Literary Culture and Religious Community in Tamil-Speaking South India. pp 106

- ^ Ruth Barnes, David Parkin. (2015) Ships and the Development of Maritime Technology on the Indian Ocean. pp. 101

- ^ "Chapter XXXVIII: At Ceylon. Rise of the Kingdom. Feats of Buddha. Topes and Monasteries. Statue of Buddha in Jade. Bo Tree. Festival of Buddha's Tooth". A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ISBN 9780791413135. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781134168118. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ISBN 9788131711200. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ Indicopleustes, Cosmas (1897). "A description of Indian Animals, and of the Island of Taprobane". Christian Topography. Book XI: 358–373.

- ^ Mcrindle, John Watson (1901). Ancient India as described in classical literature. Westminster Constable. p. 160.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Baruah, Bibhuti. Buddhist Sects and Sectarianism. 2008. p. 53

- ^ Hirakawa, Akira. Groner, Paul. A History of Indian Buddhism: From Śākyamuni to Early Mahāyāna. 2007. p. 121

- ^ Nandana Cūṭivoṅgs, Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. (2002). The iconography of Avalokiteśvara in Mainland South East Asia. pp5

- ^ Hirakawa, Akira. Groner, Paul. A History of Indian Buddhism: From Śākyamuni to Early Mahāyāna. 2007. p. 125

- ^ Sujato, Bhikkhu. Sects & Sectarianism: The Origins of Buddhist Schools. 2006. p. 59

- ^ Buddhadatta, UCR, Vol. IX, p.74

- ^ Massey, Gerald (1974). A Book of the Beginnings, Containing an Attempt to Recover and Reconstitute the Lost Origines of the Myths and Mysteries, Types and Symbols, Religion and Language, with Egypt for the Mouthpiece and Africa as the Birthplace: Egyptian origines in the British Isles. Indiana University: University Books. p. 452. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ "Beadle's Monthly: A Magazine of Today". Pennsylvania State University. 1–2: 206. 1866. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ Dervoort, J. Wesley Van (1886). The Water World: A Popular Treatise on the Broad, Broad Ocean. Its Laws; Its Phenomena; Its Products and Its Inhabitants ... with Chapters on Steamships, Light-houses, Life Saving Service ... Union publishing house. p. 367. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ Rao Bahadur Krishnaswāmi Aiyangar, Maṇimekhalai in its Historical Setting, London, 1928, p.185, 201, etc.. Available at www.archive.org [1]

- ^ Paula Richman, ”Cīttalai Cāttanār, Manimekhalai” summary in Karl H. Potter ed.,The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies: Buddhist philosophy from 350 to 600 A.D. New Delhi, 2003, pp.457–462.

- ^ Nair, R. V.; Mohan, R. S. Lal; Rao, K. Satyanarayana (1975). The dugong D̲u̲g̲o̲n̲g̲ d̲u̲g̲o̲n̲. Central Marine Fisheris Research Institute. p. 45. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781587153136. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ Lebor Gabala Erenn Vol. II (Macalister translation)

- ^ In the early 1800s, Welsh pseudohistorian Iolo Morganwg published what he claimed was mediaeval Welsh epic material, describing how Hu Gadarn had led the ancestors of the Welsh in a migration to Britain from Taprobane or "Deffrobani", aka "Summerland", said in his text to be situated "where Constantinople now is." However, this work is now considered to have been a forgery produced by Iolo Morganwg himself.

- ^ Don Quixote, Volume I, Chapter 18: the mighty emperor Alifanfaron, lord of the great isle of Trapobana.

- ^ The Retrospective Review, and Historical and Antiquarian Magazine (3 ed.). UC Southern Regional Library Facility: C. and H. Baldwyn. 1821. p. 91. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

External links

[[Category:History of Sri Lanka]] [[Category:History of Tamil Nadu]] [[Category:Tamil history]] [[Category:Sri Lankan Tamil history]]