Divine Comedy

The Divine Comedy (Italian: Divina Commedia [diˈviːna komˈmɛːdja]) is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun c. 1308 and completed around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature[1] and one of the greatest works of Western literature.[2] The poem's imaginative vision of the afterlife is representative of the medieval worldview as it existed in the Western Church by the 14th century. It helped establish the Tuscan language, in which it is written, as the standardized Italian language.[3] It is divided into three parts: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso.

The poem discusses "the state of the soul after death and presents an image of divine justice meted out as due punishment or reward",

In the poem, the pilgrim Dante is accompanied by three guides:

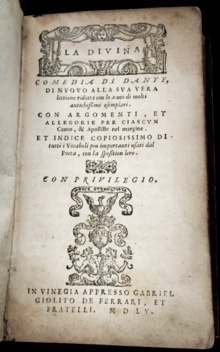

The work was originally simply titled Comedìa (pronounced [komeˈdiːa], Tuscan for "Comedy") – so also in the first printed edition, published in 1472 – later adjusted to the modern Italian Commedia. The adjective Divina was added by Giovanni Boccaccio,[13] owing to its subject matter and lofty style,[14] and the first edition to name the poem Divina Comedia in the title was that of the Venetian humanist Lodovico Dolce,[15] published in 1555 by Gabriele Giolito de' Ferrari.

Erich Auerbach said Dante was the first writer to depict human beings as the products of a specific time, place and circumstance, as opposed to mythic archetypes or a collection of vices and virtues, concluding that this, along with the fully imagined world of the Divine Comedy, suggests that the Divine Comedy inaugurated realism and self-portraiture in modern fiction.[16]

Structure and story

The Divine Comedy is composed of 14,233 lines that are divided into three cantiche (singular cantica) – Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory), and Paradiso (Paradise) – each consisting of 33 cantos (Italian plural canti). An initial canto, serving as an introduction to the poem and generally considered to be part of the first cantica, brings the total number of cantos to 100. It is generally accepted, however, that the first two cantos serve as a unitary prologue to the entire epic, and that the opening two cantos of each cantica serve as prologues to each of the three cantiche.[17][18][19]

The number three is prominent in the work, represented in part by the number of cantiche and their lengths. Additionally, the verse scheme used,

Written in the first person, the poem tells of Dante's journey through the three realms of the dead, lasting from the night before Good Friday to the Wednesday after Easter in the spring of 1300. The Roman poet Virgil guides him through Hell and Purgatory; Beatrice, Dante's ideal woman, guides him through Heaven. Beatrice was a Florentine woman he had met in childhood and admired from afar in the mode of the then-fashionable courtly love tradition, which is highlighted in Dante's earlier work La Vita Nuova.[21]

The structure of the three realms follows a common

In central Italy's political struggle between

The last word in each of the three cantiche is stelle ("stars").

Inferno

The poem begins on the night before Good Friday in the year 1300, "halfway along our life's path" (Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita). Dante is thirty-five years old, half of the biblical lifespan of 70 (Psalms 89:10, Vulgate), lost in a dark wood (understood as sin),[24][25][26] assailed by beasts (a lion, a leopard, and a she-wolf) he cannot evade and unable to find the "straight way" (diritta via) – also translatable as "right way" – to salvation (symbolized by the sun behind the mountain). Conscious that he is ruining himself and that he is falling into a "low place" (basso loco) where the sun is silent ('l sol tace), Dante is at last rescued by Virgil, and the two of them begin their journey to the underworld. Each sin's punishment in Inferno is a contrapasso, a symbolic instance of poetic justice; for example, in Canto XX, fortune-tellers and soothsayers must walk with their heads on backwards, unable to see what is ahead, because that was what they had tried to do in life:

they had their faces twisted toward their haunches

and found it necessary to walk backward,

because they could not see ahead of them.

... and since he wanted so to see ahead,

he looks behind and walks a backward path.[27]

Allegorically, the Inferno represents the Christian soul seeing sin for what it really is, and the three beasts represent three types of sin: the self-indulgent, the violent, and the malicious.

Purgatorio

Having survived the depths of Hell, Dante and Virgil ascend out of the undergloom to the Mountain of Purgatory on the far side of the world. The Mountain is on an island, the only land in the Southern Hemisphere, created by the displacement of rock which resulted when Satan's fall created Hell[30] (which Dante portrays as existing underneath Jerusalem[31]). The mountain has seven terraces, corresponding to the seven deadly sins or "seven roots of sinfulness".[32] The classification of sin here is more psychological than that of the Inferno, being based on motives, rather than actions. It is also drawn primarily from Christian theology, rather than from classical sources.[33] However, Dante's illustrative examples of sin and virtue draw on classical sources as well as on the Bible and on contemporary events.

Love, a theme throughout the Divine Comedy, is particularly important for the framing of sin on the Mountain of Purgatory. While the love that flows from God is pure, it can become sinful as it flows through humanity. Humans can sin by using love towards improper or malicious ends (

Allegorically, the Purgatorio represents the Christian life. Christian souls arrive escorted by an angel, singing

The Purgatorio demonstrates the medieval knowledge of a

Paradiso

After an initial ascension, Beatrice guides Dante through the nine

The seven lowest spheres of Heaven deal solely with the cardinal virtues of

Dante meets and converses with several great saints of the Church, including Thomas Aquinas, Bonaventure, Saint Peter, and St. John. The Paradiso is consequently more theological in nature than the Inferno and the Purgatorio. However, Dante admits that the vision of heaven he receives is merely the one his human eyes permit him to see, and thus the vision of heaven found in the Cantos is Dante's personal vision.

The Divine Comedy finishes with Dante seeing the

But already my desire and my will

were being turned like a wheel, all at one speed,

by the Love which moves the sun and the other stars.[37]

History

Manuscripts

According to the Italian Dante Society, no

Early translations

Coluccio Salutati translated some quotations from the Comedy into Latin for his De fato et fortuna in 1396–1397. The first complete translation of the Comedy was made into Latin prose by Giovanni da Serravalle in 1416 for two English bishops, Robert Hallam and Nicholas Bubwith, and an Italian cardinal, Amedeo di Saluzzo. It was made during the Council of Constance. The first verse translation, into Latin hexameters, was made in 1427–1431 by Matteo Ronto.[39]

The first translation of the Comedy into another vernacular was the prose translation into Castilian completed by Enrique de Villena in 1428. The first vernacular verse translation was that of Andreu Febrer into Catalan in 1429.[4]

Early printed editions

The first printed edition was published in Foligno, Italy, by Johann Numeister and Evangelista Angelini da Trevi on 11 April 1472.[40] Of the 300 copies printed, fourteen still survive. The original printing press is on display in the Oratorio della Nunziatella in Foligno.

| Date | Title | Place | Publisher | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1472 | La Comedia di Dante Alleghieri | Foligno | Johann Numeister and Evangelista Angelini da Trevi | First printed edition (or editio princeps) |

| 1477 | La Commedia | Venice | Wendelin of Speyer | |

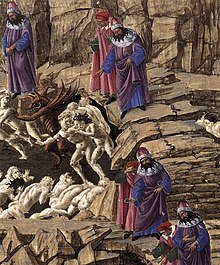

| 1481 | Comento di Christophoro Landino fiorentino sopra la Comedia di Dante Alighieri | Florence | Nicolaus Laurentii | With Cristoforo Landino's commentary in Italian, and some engraved illustrations by Baccio Baldini after designs by Sandro Botticelli |

| 1491 | Comento di Christophoro Landino fiorentino sopra la Comedia di Dante Alighieri | Venice | Pietro di Piasi | First fully illustrated edition |

| 1502 | Le terze rime di Dante | Venice | Aldus Manutius | |

| 1506 | Commedia di Dante insieme con uno diagolo circa el sito forma et misure dello inferno | Florence | Philippo di Giunta | |

| 1555 | La Divina Comedia di Dante | Venice | Gabriel Giolito | First use of "Divine" in title |

Thematic concerns

The Divine Comedy can be described simply as an

The structure of the poem is also quite complex, with mathematical and numerological patterns distributed throughout the work, particularly threes and nines. The poem is often lauded for its particularly human qualities: Dante's skillful delineation of the characters he encounters in Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise; his bitter denunciations of

Dante called the poem "Comedy" (the adjective "Divine" was added later, in the 16th century) because poems in the ancient world were classified as High ("Tragedy") or Low ("Comedy").

Scientific themes

Although the Divine Comedy is primarily a religious poem, discussing sin, virtue, and theology, Dante also discusses several elements of the

Just as, there where its Maker shed His blood,

the sun shed its first rays, and Ebro lay

beneath high Libra, and the ninth hour's rays

were scorching Ganges' waves; so here, the sun

stood at the point of day's departure when

God's angel – happy – showed himself to us.[48]

Dante travels through the centre of the Earth in the Inferno, and comments on the resulting change in the direction of gravity in Canto XXXIV (lines 76–120). A little earlier (XXXIII, 102–105), he queries the existence of wind in the frozen inner circle of hell, since it has no temperature differentials.[49]

Inevitably, given its setting, the Paradiso discusses astronomy extensively, but in the Ptolemaic sense. The Paradiso also discusses the importance of the experimental method in science, with a detailed example in lines 94–105 of Canto II:

A briefer example occurs in Canto XV of the Purgatorio (lines 16–21), where Dante points out that both theory and experiment confirm that the

Galileo Galilei is known to have lectured on the Inferno, and it has been suggested that the poem may have influenced some of Galileo's own ideas regarding mechanics.[51]

Influences

| This article is part of the series on the |

| Italian language |

|---|

| History |

| Literature and other |

| Grammar |

| Alphabet |

| Phonology |

Classical

Without access to the works of Homer, Dante used Virgil,

Besides Dante's fellow poets, the classical figure that most influenced the Comedy is Aristotle. Dante built up the philosophy of the Comedy with the works of Aristotle as a foundation, just as the scholastics used Aristotle as the basis for their thinking. Dante knew Aristotle directly from Latin translations of his works and indirectly quotations in the works of Albertus Magnus.[56] Dante even acknowledges Aristotle's influence explicitly in the poem, specifically when Virgil justifies the Inferno's structure by citing the Nicomachean Ethics.[57] In the same canto, Virgil draws on Cicero's De Officiis to explain why sins of the intellect are worse than sins of violence, a key point that would be explored from canto XVIII to the end of the Inferno.[58]

Christian

The Divine Comedy's language is often derived from the phraseology of the Vulgate. This was the only translation of the Bible Dante had access to, as it was one the vast majority of scribes were willing to copy during the Middle Ages. This includes five hundred or so direct quotes and references Dante derives from the Bible (or his memory of it). Dante also treats the Bible as a final authority on any matter, including on subjects scripture only approaches allegorically.[59]

The Divine Comedy is also a product of Scholasticism, especially as expressed by St. Thomas Aquinas.[60][61] This influence is most pronounced in the Paradiso, where the text's portrayals of God, the beatific vision, and substantial forms all align with scholastic doctrine.[62] It is also in the Paradiso that Aquinas and fellow scholastic St. Bonaventure appear as characters, introducing Dante to all of Heaven's wisest souls. Despite all this, there are issues on which Dante diverges from the scholastic doctrine, such as in his unbridled praise for poetry.[63]

The Apocalypse of Peter is one of the earliest examples of a Christian-Jewish katabasis, a genre of explicit depictions of heaven and hell. Later works inspired by it include the Apocalypse of Thomas in the 2nd–4th century, and more importantly, the Apocalypse of Paul in the 4th century. Despite a lack of "official" approval, the Apocalypse of Paul would go on to be popular for centuries, possibly due to its popularity among the medieval monks that copied and preserved manuscripts in the turbulent centuries following the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The Divine Comedy belongs to the same genre[64] and was influenced by the Apocalypse of Paul.[65][66]

Islamic

Dante lived in a Europe of substantial literary and philosophical contact with the Muslim world, encouraged by such factors as Averroism ("Averrois, che'l gran comento feo" Commedia, Inferno, IV, 144, meaning "Averrois, who wrote the great comment") and the patronage of Alfonso X of Castile. Of the twelve wise men Dante meets in Canto X of the Paradiso, Thomas Aquinas and, even more so, Siger of Brabant were strongly influenced by Arabic commentators on Aristotle.[67] Medieval Christian mysticism also shared the Neoplatonic influence of Sufis such as Ibn Arabi. Philosopher Frederick Copleston argued in 1950 that Dante's respectful treatment of Averroes, Avicenna, and Siger of Brabant indicates his acknowledgement of a "considerable debt" to Islamic philosophy.[67]

In 1919,

Many scholars have not been satisfied that Dante was influenced by the Kitab al Miraj. The 20th century Orientalist Francesco Gabrieli expressed skepticism regarding the claimed similarities, and the lack of evidence of a vehicle through which it could have been transmitted to Dante.[70] The Italian philologist Maria Corti pointed out that, during his stay at the court of Alfonso X, Dante's mentor Brunetto Latini met Bonaventura de Siena, a Tuscan who had translated the Kitab al Miraj from Arabic into Latin. Corti speculates that Brunetto may have provided a copy of that work to Dante.[71] René Guénon, a Sufi convert and scholar of Ibn Arabi, confirms in The Esoterism of Dante the theory of the Islamic influence (direct or indirect) on Dante.[72] Palacios' theory that Dante was influenced by Ibn Arabi was satirized by the Turkish academic Orhan Pamuk in his novel The Black Book.[73]

In addition to that, it has been claimed that

Literary influence in the English-speaking world and beyond

The Divine Comedy was not always as well-regarded as it is today. Although recognized as a masterpiece in the centuries immediately following its publication,[76] the work was largely ignored during the Enlightenment, with some notable exceptions such as Vittorio Alfieri; Antoine de Rivarol, who translated the Inferno into French; and Giambattista Vico, who in the Scienza nuova and in the Giudizio su Dante inaugurated what would later become the romantic reappraisal of Dante, juxtaposing him to Homer.[77] The Comedy was "rediscovered" in the English-speaking world by William Blake – who illustrated several passages of the epic – and the Romantic writers of the 19th century. Later authors such as T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Samuel Beckett, C. S. Lewis and James Joyce have drawn on it for inspiration. The poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was its first American translator,[78] and modern poets, including Seamus Heaney,[79] Robert Pinsky, John Ciardi, W. S. Merwin, and Stanley Lombardo, have also produced translations of all or parts of the book. In Russia, beyond Pushkin's translation of a few tercets,[80] Osip Mandelstam's late poetry has been said to bear the mark of a "tormented meditation" on the Comedy.[81] In 1934, Mandelstam gave a modern reading of the poem in his labyrinthine "Conversation on Dante".[82] In T. S. Eliot's estimation, "Dante and Shakespeare divide the world between them. There is no third."[83] For Jorge Luis Borges the Divine Comedy was "the best book literature has achieved".[84]

English translations

The Divine Comedy has been translated into English more times than any other language, and new English translations of the Divine Comedy continue to be published regularly. Notable English translations of the complete poem include the following.[85]

| Year | Translator | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1805–1814 | Henry Francis Cary | An older translation, widely available online. |

| 1867 | Henry Wadsworth Longfellow | Unrhymed terzines. The first U.S. translation, raising American interest in the poem. It is still widely available, including online. |

| 1891–1892 | Charles Eliot Norton | Prose translation used by Great Books of the Western World. Available online in three parts (Hell, Purgatory, Paradise) at Project Gutenberg. |

| 1933–1943 | Laurence Binyon | Terza rima. Translated with assistance from Ezra Pound. Used in The Portable Dante (Viking, 1947). |

| 1949–1962 | Dorothy L. Sayers | Translated for Penguin Classics, intended for a wider audience, and completed by Barbara Reynolds after Sayers's death. |

| 1969 | Thomas G. Bergin | Cast in blank verse with illustrations by Leonard Baskin.[86] |

| 1954–1970 | John Ciardi | His Inferno was recorded and released by Folkways Records in 1954. |

| 1970–1991 | Charles S. Singleton | Literal prose version with extensive commentary; 6 vols. |

| 1981 | C. H. Sisson | Available in Oxford World's Classics. |

| 1980–1984 | Allen Mandelbaum | Available online at World of Dante and alongside Teodolinda Barolini's commentary at Digital Dante. |

| 1967–2002 | Mark Musa | An alternative Penguin Classics version. |

| 2000–2007 | Robert and Jean Hollander | Online as part of the Princeton Dante Project. Contains extensive scholarly footnotes. |

| 2002–2004 | Anthony M. Esolen |

Modern Library Classics edition. |

| 2006–2007 | Robin Kirkpatrick | A third Penguin Classics version, replacing Musa's. |

| 2010 | Burton Raffel | A Northwestern World Classics version. |

| 2013 | Clive James | A poetic version in quatrains. |

A number of other translators, such as Robert Pinsky, have translated the Inferno only.

In popular culture

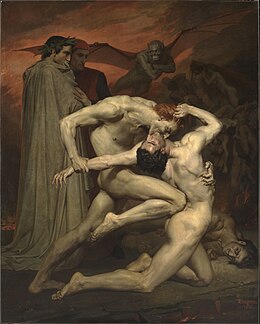

The Divine Comedy has been a source of inspiration for countless artists for almost seven centuries. There are many references to Dante's work in

See also

- Allegory in the Middle Ages

- Dream vision

- List of cultural references in Divine Comedy

- Seven Heavens

- Theological fiction

Citations

- ^ For example, Encyclopedia Americana, 2006, Vol. 30. p. 605: "the greatest single work of Italian literature;" John Julius Norwich, The Italians: History, Art, and the Genius of a People, Abrams, 1983, p. 27: "his tremendous poem, still after six and a half centuries the supreme work of Italian literature, remains – after the legacy of ancient Rome – the grandest single element in the Italian heritage;" and Robert Reinhold Ergang, The Renaissance, Van Nostrand, 1967, p. 103: "Many literary historians regard the Divine Comedy as the greatest work of Italian literature. In world literature it is ranked as an epic poem of the highest order."

- ISBN 978-0-15-195747-7. See also Western canonfor other "canons" that include the Divine Comedy.

- ^ See Lepschy, Laura; Lepschy, Giulio (1977). The Italian Language Today. Or any other history of Italian language.

- ^ a b c Vallone, Aldo. "Commedia" (trans. Robin Treasure). In: Lansing (ed.), The Dante Encyclopedia, pp. 181–184.

- ISBN 1-59308-051-4: "the key fiction of the Divine Comedy is that the poem is true."

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on p. 19.

- ISBN 0-8369-5521-8.

- ^ Fordham College Monthly. Vol. XL. Fordham University. December 1921. p. 76. Archived from the original on 4 August 2023. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- OCLC 7671339.

- ^ a b Emmerson, Richard K., and Ronald B. Herzman. "Revelation". In: Lansing (ed.), The Dante Encyclopedia, pp. 742–744.

- ^ Ferrante, Joan M. "Beatrice". In: Lansing (ed.), The Dante Encyclopedia, pp. 87–94.

- ^ Picone, Michelangelo. "Bernard, St." (trans. Robin Treasure). In: Lansing (ed.), The Dante Encyclopedia, pp. 99–100.

- Enciclopedia Italiana (in Italian). Archived from the originalon 18 February 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ Hutton, Edward (29 August 2014). Giovanni Boccaccio, a Biographical Study. p. 273. Archived from the original on 21 March 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Ronnie H. Terpening, Lodovico Dolce, Renaissance Man of Letters (Toronto, Buffalo, London: University of Toronto Press, 1997), p. 166.

- ISBN 978-1-59017-219-3.

- ^ Dante The Inferno A Verse Translation, by Professor Robert and Jean Hollander, p. 43.

- ^ Epist. XIII, 43–48.

- ^ Wilkins, E.H., The Prologue to the Divine Comedy Annual Report of the Dante Society, pp. 1–7.

- ^ Kaske, Robert Earl, et al. Medieval Christian Literary Imagery: A Guide to Interpretation. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988. p. 164.

- ^ Shaw 2014, pp. xx, 100–101, 108.

- ^ Eiss 2017, p. 8.

- ^ Trone 2000, pp. 362–364.

- ^ "Inferno, la Divina Commedia annotata e commentata da Tommaso Di Salvo, Zanichelli, Bologna, 1985". Abebooks.it. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ Lectura Dantis, Società dantesca italiana.

- ^ Online sources include [1] Archived 11 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine, [2] Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, [3] [4] Archived 23 February 2004 at the Wayback Machine, "Le caratteristiche dell'opera". Archived from the original on 2 December 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2009., "Selva Oscura". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- ^ Inferno, Canto XX, lines 13–15 and 38–39, Mandelbaum translation.

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory, notes on p. 75.

- ^ Carlyle-Okey-Wicksteed, Divine Comedy, "Notes to Dante's Inferno".

- ^ Inferno, Canto 34, lines 121–126.

- ^ Barolini, Teodolinda. "Hell." In: Lansing (ed.), The Dante Encyclopedia, pp. 472–477.

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory, Introduction, pp. 65–67 (Penguin, 1955).

- ^ Robin Kirkpatrick, Purgatorio, Introduction, p. xiv (Penguin, 2007).

- ^ Carlyle-Oakey-Wickstead, Divine Comedy, "Notes on Dante's Purgatory.

- ^ "The Letter to Can Grande," in Literary Criticism of Dante Alighieri, translated and edited by Robert S. Haller (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1973), p. 99.

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Paradise, notes on Canto XXXIII.

- ^ Paradiso, Canto XXXIII, lines 142–145, C. H. Sisson translation.

- ^ "Elenco Codici". Dante Online. Archived from the original on 3 June 2009. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- ^ Michele Zanobini, "Per Un Dante Latino": The Latin Translations of the Divine Comedy in Nineteenth-Century Italy Archived 20 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, PhD dissertation. (Johns Hopkins University, 2016), pp. 16–17, 21–22.

- ISBN 0-415-93930-5, p. 360.

- ^ "Epistle to Can Grande". faculty.georgetown.edu. Archived from the original on 29 January 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, Introduction, p. 16 (Penguin, 1955).

- ^ "World History Encyclopedia". Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Boccaccio also quotes the initial triplet:"Ultima regna canam fluvido contermina mundo, / spiritibus quae lata patent, quae premia solvunt / pro meritis cuicumque suis". For translation and more, see Guyda Armstrong, Review of Giovanni Boccaccio. Life of Dante. J. G. Nichols, trans. London: Hesperus Press, 2002.

- S2CID 244492114.

- ^ Michael Caesar, Dante: The Critical Heritage, Routledge, 1995, pp. 288, 383, 412, 631.

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory, notes on p. 286.

- ^ Purgatorio, Canto XXVII, lines 1–6, Mandelbaum translation.

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Inferno, notes on p. 284.

- ^ Paradiso, Canto II, lines 94–105, Mandelbaum translation.

- S2CID 16106719. Archived from the original(PDF) on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ Moore, Edward (1968) [1896]. Studies in Dante, First Series: Scripture and Classical Authors in Dante. New York: Greenwood Press. p. 4.

- ISBN 978-0-8047-1860-8. Archivedfrom the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- from the original on 21 March 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Commentary to Paradiso, IV.90 by Robert and Jean Hollander, The Inferno: A Verse Translation (New York: Anchor Books, 2002), as found on Dante Lab, http://dantelab.dartmouth.edu Archived 14 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lafferty, Roger. "The Philosophy of Dante Archived 29 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine", pg. 4

- ^ Inferno, Canto XI, lines 70–115, Mandelbaum translation.

- ^ Cornell University, Visions of Dante: Glossary Archived 29 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Moore, Edward. Studies in Dante, First Series: Scripture and Classical Authors in Dante Archived 29 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford: Clarendon, 1969 [1896], pp. 4, 8, 47–48.

- ^ Toynbee, Paget. Dictionary of Dante A Dictionary of the works of Dante Archived 25 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine, p. 532.

- ^ Alighieri, Dante (1904). Philip Henry Wicksteed, Herman Oelsner (ed.). The Paradiso of Dante Alighieri (fifth ed.). J.M. Dent and Company. p. 126.

- ^ Commentary to Paradiso, I.1–12 and I.96–112 by John S. Carroll, Paradiso: A Verse Translation (New York: Anchor Books, 2007), as found on Dante Lab, http://dantelab.dartmouth.edu Archived 14 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Commentary to Paradiso, XXXII.31–32 by Robert and Jean Hollander, Paradiso: A Verse Translation (New York: Anchor Books, 2007), as found on Dante Lab, http://dantelab.dartmouth.edu Archived 14 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Maurer, Christian (1965) [1964]. Schneemelcher, Wilhelm (ed.). New Testament Apocrypha, Volume Two: Writings Relating to the Apostles; Apocalypses and Related Subjects. Translated by Wilson, Robert McLachlan. Philadelphia: Westminster Press. p. 663–668.

- ^ Silverstein, Theodore (1935). Visio Sancti Pauli: The History of the Apocalypse in Latin, Together with Nine Texts. London: Christophers. pp. 3–5, 91.

- JSTOR 20466112.

- ^ a b Copleston, Frederick (1950). A History of Philosophy. Vol. 2. London: Continuum. p. 200.

- ^ I. Heullant-Donat and M.-A. Polo de Beaulieu, "Histoire d'une traduction," in Le Livre de l'échelle de Mahomet, Latin edition and French translation by Gisèle Besson and Michèle Brossard-Dandré, Collection Lettres Gothiques, Le Livre de Poche, 1991, p. 22 with note 37.

- ISBN 978-1-908092-02-1.

- S2CID 143999655.

- ^ "Errore". Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2007.

- Guenon, René(1925). The Esoterism of Dante.

- JSTOR 1466522.

- ISBN 978-0-7425-6296-7.

- ISBN 978-1-315-08349-0. Archivedfrom the original on 7 August 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- Chaucer wrote in the Monk's Tale, "Redeth the grete poete of Ytaille / That highte Dant, for he kan al devyse / Fro point to point; nat o word wol he faille".

- from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-252-03063-5.

- ^ Seamus Heaney, "Envies and Identifications: Dante and the Modern Poet." The Poet's Dante: Twentieth-Century Responses. Ed. Peter S. Hawkins and Rachel Jacoff. New York: Farrar, 2001. pp. 239–258.

- ^ Isenberg, Charles. "Dante in Russia." In: Lansing (ed.), The Dante Encyclopedia, pp. 276–278.

- ^ Glazova, Marina (November 1984). "Mandel'štam and Dante: The Divine Comedy in Mandel'štam's Poetry of the 1930s Archived 29 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine". Studies in Soviet Thought. 28 (4).

- from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ T. S. Eliot (1950) "Dante." Selected Essays, pp. 199–237. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

- ^ Jorge Luis Borges, "Selected Non-Fictions". Ed. Eliot Weinberger. Trans. Esther Allen et al. New York: Viking, 1999. p. 303.

- ^ A comprehensive listing and criticism, covering the period 1782–1966, of English translations of at least one of the three cantiche is given by Gilbert F. Cunningham, The Divine Comedy in English: A Critical Bibliography, 2 vols. (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1965–1967), esp. vol. 2, pp. 5–9.

- ^ Dante Alighieri. Bergin, Thomas G. trans. Divine Comedy. Grossman Publishers; 1st edition (1969) .

- ^ "Dante et Virgile – William Bouguereau". Musée d'Orsay. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- The Florentine. Archivedfrom the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

Bibliography

- Eiss, Harry (2017). Seeking God in the Works of T. S. Eliot and Michelangelo. New Castle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. ISBN 978-1-4438-4390-4.

- Shaw, Prue (2014). Reading Dante: From Here to Eternity. New York: Liveright Publishing. ISBN 978-1-63149-006-4.

- Trone, George Andrew (2000). "Exile". In Lansing, Richard (ed.). The Dante Encyclopedia. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-87611-7.

Further reading

- Ziolkowski, Jan M. (2015). Dante and Islam. Fordham University Press, New York. ISBN 0823263878.

External links

- Divine Comedy at Standard Ebooks

- Princeton Dante Project Website that offers the complete text of the Divine Comedy (and Dante's other works) in Italian and English along with audio accompaniment in both languages. Includes historical and interpretive annotation.

- (in Italian) Full text of the Commedia Archived 27 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Dante Dartmouth Project: Full text of more than 70 Italian, Latin, and English commentaries on the Commedia, ranging in date from 1322 (Iacopo Alighieri) to the 2000s (Robert Hollander)

- A Dictionary of the Proper Names and Notable Matters in the Works of Dante by Paget Toynbee (Oxford: Clarendon, 1898)

- Columbia University's Digital Dante features the full text in Italian alongside English translations from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Allen Mandelbaum. Includes English commentary from Teodolinda Barolini as well as multimedia resources relating to the Divine Comedy.

Divine Comedy public domain audiobook at LibriVox (in English and Italian)

Divine Comedy public domain audiobook at LibriVox (in English and Italian)- Going Through Hell: The Divine Dante exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, 9 April – 16 July 2023