Culture of Italy

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (October 2024) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Italy |

|---|

|

| People |

| Traditions |

The culture of Italy encompasses the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, and customs of the

Italy is widely recognised as a

The essence of Italian culture is reflected in its art, music, cinema, style, and food. Italy gave birth to opera and has been instrumental in classical music, producing renowned composers such as Antonio Vivaldi, Gioachino Rossini, Giuseppe Verdi, and Giacomo Puccini. Its rich cultural heritage includes significant contributions to ballet, folk dances such as tarantella, and the improvisational theater of commedia dell'arte.[4]

The country boasts iconic cities that have shaped world culture. Rome, the ancient capital of the Roman civilisation and seat of the Catholic Church, stands alongside Florence, the heart of the Renaissance. Venice, with its unique canal system, and Milan, a global fashion capital, further exemplify Italy's cultural significance. Each city tells a story of artistic, historical, and innovative achievement.[5]

Italy has been the starting point of transformative global phenomena, including the Roman Republic, the Latin alphabet, civil law, the Age of Discovery, and the Scientific Revolution. It is home to the most UNESCO World Heritage Sites (60) and has produced numerous notable individuals who have made lasting contributions to human knowledge and creativity.

Arts

Italian art has influenced several major movements throughout the centuries and has produced several great artists, including painters, architects, and sculptors. Today, Italy has an essential place in the international art scene, with several major art galleries, museums, and exhibitions; major artistic centres in the country include Rome, Florence, Venice, Milan, Turin, Genoa, Naples, Palermo, and other cities. Italy is home to 60 World Heritage Sites, the largest number of any country in the world.

Since ancient times,

Italy was the main centre of artistic developments throughout the

However, Italy maintained a presence in the international art scene from the mid-19th century onwards, with cultural movements such as the

.Architecture

Italy is renowned for its rich architectural heritage, from ancient Rome to modern design. Italian architects pioneered the use of arches, domes, and vaults, laid the foundations of Renaissance architecture, and inspired movements such as Palladianism and Neoclassicism. Italian cities are home to a wide range of historical styles that influenced the built environment worldwide.

Ancient and classical

Architecture in Italy began with Etruscan and Greek settlements, which influenced the development of Roman architecture. Roman achievements included aqueducts, amphitheatres, temples, and urban planning. The legacy of Roman engineering is visible in structures such as the Colosseum and the Pantheon, as well as in sites such as Pompeii.[8]

Early Christian and Byzantine

With Christianity's spread, Roman forms were adapted into the basilica—long, rectangular churches richly decorated with mosaics.[9] Ravenna became a center of Byzantine art and architecture, while Old St. Peter's Basilica, begun in the 4th century, set the template for medieval church design.

Romanesque and Gothic

Between the 9th and 12th centuries, Romanesque architecture flourished, marked by rounded arches, vaults, and elaborate cloisters. Notable examples include the Leaning Tower of Pisa and the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio in Milan.[10]

Renaissance and Baroque

The Italian Renaissance (14th–16th centuries) revived classical forms and emphasised symmetry and proportion. Filippo Brunelleschi's dome for Florence Cathedral and Donato Bramante's work on St. Peter's Basilica exemplify this era's innovations.[11] Andrea Palladio's harmonious villas in the Veneto region, such as the Villa La Rotonda, became a model for Western architecture.[12]

In the 17th century, Baroque architecture emerged, emphasising grandeur and theatricality, as seen in churches and palaces throughout Rome and Naples.[13] The style continued into Rococo and was later tempered by the classical restraint of Neoclassicism.[14][15]

Cinema

The history of

After a period of decline in the 1920s, the Italian film industry was revitalized in the 1930s with the arrival of sound film. A popular Italian genre during this period, the Telefoni Bianchi, consisted of comedies with glamorous backgrounds.[29] Calligrafismo was instead in a sharp contrast to Telefoni Bianchi-American style comedies and is rather artistic, highly formalistic, expressive in complexity, and deals mainly with contemporary literary material.[30] Cinema was later used by Benito Mussolini, who founded Rome's renowned Cinecittà studio also for the production of Fascist propaganda until World War II.[31]

After the war, Italian film was widely recognised and exported until an artistic decline around the 1980s.

As the country grew wealthier in the 1950s, a form of neorealism known as pink neorealism succeeded, and starting from the 1950s through the commedia all'italiana genre, and other film genres, such as sword-and-sandal followed as spaghetti Westerns, were popular in the 1960s and 1970s.[36] Actresses such as Sophia Loren, Giulietta Masina, and Gina Lollobrigida achieved international stardom during this period. Erotic Italian thrillers, or gialli, produced by directors such as Mario Bava and Dario Argento in the 1970s, also influenced the horror genre worldwide.[37] In recent years, the Italian scene has received only occasional international attention, with films such as Cinema Paradiso, written and directed by Giuseppe Tornatore; Mediterraneo, directed by Gabriele Salvatores; Il Postino: The Postman, with Massimo Troisi; Life Is Beautiful, directed by Roberto Benigni; and The Great Beauty, directed by Paolo Sorrentino.[38]

The aforementioned Cinecittà studio is today the largest film and television production facility in

Italy is the most awarded country at the

Comics

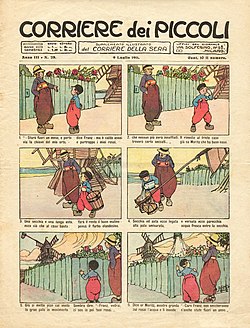

Italian comics (Fumetti) officially began on 27 December 1908 with the first issue of Corriere dei Piccoli. Attilio Mussino contributed various characters, including Bilbolbul, a little Black child whose surreal adventures unfolded in a fantastical Africa.

In 1932, publisher Lotario Vecchi launched Jumbo, featuring only North American authors.[45] With a circulation of 350,000, it cemented comics as a mainstream medium in Italy. Vecchi later brought the title to Spain.

That same year, the first Italian Disney comic, Topolino (Mickey Mouse), debuted, published by Nerbini in Florence. In 1935, Mondadori's subsidiary API took over the franchise.

In 1945, Hugo Pratt, with Mario Faustinelli and Alberto Ongaro, created Asso di Picche while at the Venice Academy of Fine Arts. Their distinct style earned them recognition as the Venetian school of comics.

In 1948, Gian Luigi Bonelli launched the successful Western series Tex Willer, which became the prototype for Bonelliani—adventure comics in digest format. Later series included Zagor (1961), Mister No (1975), Martin Mystère (1982), and Dylan Dog (1986). These focused on adventure themes—Western, horror, mystery, or science fiction—and remain the most popular comic format in Italy.

Italy also produces many

Notable Disney artists include Bonvi, Marco Rota, Romano Scarpa, Giorgio Cavazzano, Giovan Battista Carpi, and Guido Martina. The best-known Italian Disney character is Paperinik (Duck Avenger or Phantom Duck).

Italy also produces children's and teen comics, including Gormiti (based on a toy line), and Angel's Friends and Winx Club, both tied to popular animated series.

Dance

Fashion and design

Italian fashion has a long tradition. Milan, Florence and Rome are Italy's main fashion capitals. According to Top Global Fashion Capital Rankings 2013 by Global Language Monitor, Rome ranked sixth worldwide while Milan was twelfth. Previously, in 2009, Milan was declared as the "fashion capital of the world" by Global Language Monitor itself.[48] Currently, Milan and Rome, annually compete with other major international centres, such as Paris, New York, London, and Tokyo.

The Italian fashion industry is one of the country's most important manufacturing sectors. The majority of the older Italian couturiers are based in Rome. However, Milan is seen as the fashion capital of Italy because many well-known designers are based there and it is the venue for the Italian designer collections. Major Italian fashion labels, such as

Accessory and jewellery labels, such as Bulgari, Luxottica, and Buccellati have been founded in Italy and are internationally acclaimed, and Luxottica is the world's largest eyewear company. Also, the fashion magazine Vogue Italia, is considered one of the most prestigious fashion magazines in the world.[49] The talent of young, creative fashion is also promoted, as in the ITS young fashion designer competition in Trieste.[50]

Italy is also prominent in the field of design, notably interior design, architectural design,

Italy is recognised as a worldwide trendsetter and leader in design.

Literature

Formal Latin literature began in 240 BC with the first stage play performed in Rome.[57] Latin literature has remained highly influential, with notable writers such as Pliny the Elder, Pliny the Younger, Virgil, Horace, Propertius, Ovid, and Livy. The Romans were also known for their oral tradition, poetry, drama, and epigrams.[58] In the early 13th century, Francis of Assisi was considered by literary critics as the first Italian poet, with his religious song Canticle of the Sun.[59]

A literary movement also emerged in 13th-century Sicily, at the court of Emperor Frederick II, where lyrics inspired by Provençal themes were composed in a refined vernacular. Among the poets was notary Giacomo da Lentini, credited with inventing the sonnet, although the most famous early sonneteer was Petrarch.[60]

Guido Guinizelli is regarded as the founder of the Dolce Stil Novo, a school that introduced a philosophical approach to love poetry. Its pure style influenced Guido Cavalcanti and Dante Alighieri, whose works helped establish modern Italian. Dante's masterpiece, The Divine Comedy, is considered one of the finest literary achievements worldwide;[56] he also developed the intricate poetic form known as terza rima.

The 14th century saw Petrarch and Giovanni Boccaccio imitate classical models while cultivating individual artistic voices. Petrarch's collection Il Canzoniere became a cornerstone of lyric poetry, while Boccaccio's The Decameron remains one of the most celebrated short story collections.[61]

Renaissance authors such as Niccolò Machiavelli wrote enduring works such as The Prince, a realist treatise on power. Ludovico Ariosto continued the chivalric romance with Orlando Furioso, and Baldassare Castiglione outlined the ideal courtier in The Book of the Courtier. Torquato Tasso's epic Jerusalem Delivered blended Christian themes with classical form, adhering to Aristotelian unity.

Italian writers also pioneered the fairy tale genre. Giovanni Francesco Straparola's The Facetious Nights of Straparola (1550–1555) and Giambattista Basile's Pentamerone (1634) are among the earliest printed fairy tales in Europe.[63][64][65]

In the early 17th century,

Romanticism aligned with the

In the late 19th century, the realist movement Verismo emerged, led by Giovanni Verga and Luigi Capuana. At the same time, Emilio Salgari published popular adventure novels, including the Sandokan series.[67] In 1883, Carlo Collodi released The Adventures of Pinocchio, now among the most translated non-religious books globally.[68]

In the early 20th century, Futurism introduced experimental language glorifying speed and modernity, exemplified by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti's Manifesto of Futurism.[69]

Modern literary figures include Gabriele D'Annunzio; Nobel laureates Giosuè Carducci (1906), Grazia Deledda (1926), Luigi Pirandello (1936), Salvatore Quasimodo (1959), Eugenio Montale (1975), and Dario Fo (1997); and internationally acclaimed writers such as Italo Calvino and Umberto Eco.[70]

Music

From

Italy's most famous composers include the

Italy is widely known for being the birthplace of opera.

Introduced in the early 1920s,

Italy contributed to the development of

Producers such as

Philosophy

Over the ages, Italian philosophy and literature had a vast influence on

Italian Medieval philosophy was mainly Christian, and included philosophers and theologians such as Thomas Aquinas, the foremost classical proponent of natural theology and the father of Thomism, who reintroduced Aristotelian philosophy to Christianity.[88] Notable Renaissance philosophers include: Giordano Bruno, one of the major scientific figures of the western world; Marsilio Ficino, one of the most influential humanist philosophers of the period; and Niccolò Machiavelli, one of the main founders of modern political science. Machiavelli's most famous work was The Prince, whose contribution to the history of political thought is the fundamental break between political realism and political idealism.[89] Italy was also affected by the Enlightenment, a movement which was a consequence of the Renaissance.[90] University cities such as Padua, Bologna and Naples remained centres of scholarship and the intellect, with several philosophers such as Giambattista Vico (widely regarded as being the founder of modern Italian philosophy)[91] and Antonio Genovesi.[90] Cesare Beccaria was a significant Enlightenment figure and is now considered one of the fathers of classical criminal theory as well as modern penology.[86] Beccaria is famous for his On Crimes and Punishments (1764), a treatise that served as one of the earliest prominent condemnations of torture and the death penalty and thus a landmark work in anti-death penalty philosophy.[90]

Italy also had a renowned philosophical movement in the 1800s, with

Early Italian feminists include Sibilla Aleramo, Alaide Gualberta Beccari, and Anna Maria Mozzoni, although proto-feminist philosophies had previously been touched upon by earlier Italian writers such as Christine de Pizan, Moderata Fonte, and Lucrezia Marinella. Italian physician and educator Maria Montessori is credited with the creation of the philosophy of education that bears her name, an educational philosophy now practised throughout the world.[87] Giuseppe Peano was one of the founders of analytic philosophy and contemporary philosophy of mathematics. Recent analytic philosophers include Carlo Penco, Gloria Origgi, Pieranna Garavaso, and Luciano Floridi.[82]

Sculpture

The art of sculpture in the Italian peninsula has its roots in ancient times. In the archaic period, when Etruscan cities dominated central Italy and the adjacent sea, Etruscan sculpture flourished. The name of an individual artist, Vulca, who worked at Veii, has been identified. He has left a terracotta Apollo and other figures, and can perhaps claim the distinction of being the most ancient master in the long history of Italian art.

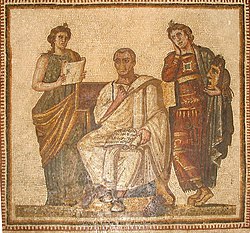

A significant development of this art occurred between the 6th century BC and 5th century AD during the growth of the

During the Middle Ages, large sculpture was largely religious. Carolingian artists (named after Charlemagne's family) in northern Italy created sculpture for covers of Bibles, as decoration for parts of church altars, and for crucifixes and giant candlesticks placed on altars.

In the late 13th century,

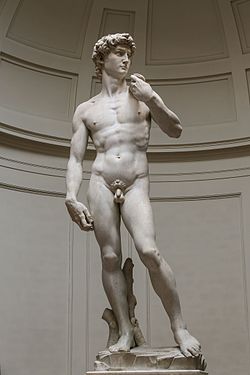

The greatest sculptor of the early Renaissance was Donatello.[95] In 1430, he produced a bronze statue of David, which re-established the classical idea of beauty in the naked human body. Conceived fully in the round and independent of any architectural surroundings, it was the first major work of Renaissance sculpture. Among the other brilliant sculptors of the 15th century were Jacopo della Quercia, Michelozzo, Bernardo and Antonio Rossellino, Giambologna, and Agostino di Duccio.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini was the most important sculptor of the Baroque period.[97] He combined emotional and sensual freedom with theatrical presentation and an almost photographic naturalism. Bernini's saints and other figures seem to sit, stand, and move as living people—and the viewer becomes part of the scene. This involvement of the spectator is a basic characteristic of Baroque sculpture. One of his most famous works is Ecstasy of Saint Teresa.

The Neoclassical movement arose in the late 18th century. The members of this very international school restored what they regarded as classical principles of art. They were direct imitators of ancient Greek sculptors, and emphasised classical drapery and the nude. The leading Neoclassical artist in Italy was Antonio Canova, who like many other foreign neoclassical sculptors including Bertel Thorvaldsen was based in Rome. His ability to carve pure white Italian marble has seldom been equalled. Most of his statues are in European collections, but the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City owns important works, including Perseus and Cupid and Psyche.

In the 20th century, many Italians played leading roles in the development of modern art. Futurist sculptors tried to show how space, movement, and time affected form. These artists portrayed objects in motion, rather than their appearance at any particular moment. An example is Umberto Boccioni's Unique Forms of Continuity in Space.

Theatre

During the 16th century and on into the 18th century,

The first recorded commedia dell'arte performances came from Rome as early as 1551,[103] and was performed outdoors in temporary venues by professional actors who were costumed and masked, as opposed to commedia erudita, which were written comedies, presented indoors by untrained and unmasked actors.[104] By the mid-16th century, specific troupes of commedia performers began to coalesce, and by 1568 the Gelosi became a distinct company. Commedia often performed inside in court theatres or halls, and also in some fixed theatres such as Teatro Baldrucca in Florence. Flaminio Scala, who had been a minor performer in the Gelosi published the scenarios of the commedia dell'arte around the start of the 17th century, really in an effort to legitimise the form—and ensure its legacy. These scenarios are highly structured and built around the symmetry of the various types in duet: two Zanni, vecchi, innamorate and innamorati, among others.[105]

In the commedia dell'arte, female roles were played by women, documented as early as the 1560s, making them the first known professional actresses in Europe since antiquity. Lucrezia Di Siena, whose name is on a contract of actors from 10 October 1564, has been referred to as the first Italian actress known by name, with Vincenza Armani and Barbara Flaminia as the first primadonnas and the first well-documented actresses in Europe.[109]

The

At first, ballets were woven into the midst of an opera to allow the audience a moment of relief from the dramatic intensity. By the mid-17th century, Italian ballets in their entirety were performed in between the acts of an opera. Over time, Italian ballets became part of theatrical life: ballet companies in Italy's major opera houses employed an average of four to twelve dancers; in 1815 many companies employed anywhere from eighty to one hundred dancers.[112]

Carlo Goldoni, who wrote a few scenarios starting in 1734, superseded the comedy of masks and the comedy of intrigue by representations of actual life and manners through the characters and their behaviours. He rightly maintained that Italian life and manners were susceptible to artistic treatment such as had not been given them before. Italian theatre has been active in producing contemporary European work and in staging revivals, including the works of Luigi Pirandello and Dario Fo.

The Teatro di San Carlo in Naples is the oldest continuously active venue for public opera in the world, opening in 1737, decades before both Milan's La Scala and Venice's La Fenice theatres.[73]

Visual art

The history of Italian visual arts is significant to the history of

Roman art was influenced by Greece and can in part be taken as a descendant of ancient Greek painting. Roman painting does have its own unique characteristics. The only surviving Roman paintings are wall paintings, many from villas in Campania, in southern Italy. Such paintings can be grouped into four main "styles" or periods[113] and may contain the first examples of trompe-l'œil, pseudo-perspective, and pure landscape.[114]

Panel painting becomes more common during the

The

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the High Renaissance gave rise to a stylised art known as Mannerism. In place of the balanced compositions and rational approach to perspective that characterised art at the dawn of the 16th century, the Mannerists sought instability, artifice, and doubt. The unperturbed faces and gestures of Piero della Francesca and the calm Virgins of Raphael are replaced by the troubled expressions of Pontormo and the emotional intensity of El Greco.

In the 17th century, among the greatest painters of Italian Baroque are Caravaggio, Annibale Carracci, Artemisia Gentileschi, Mattia Preti, Carlo Saraceni, and Bartolomeo Manfredi. Subsequently, in the 18th century, Italian Rococo was mainly inspired by French Rococo, since France was the founding nation of that particular style, with artists such as Giovanni Battista Tiepolo and Canaletto.

In the 19th century, major Italian

Spatialism was founded by the Italian artist Lucio Fontana as the movimento spaziale, its tenets were repeated in manifestos between 1947 and 1954. Combining elements of concrete art, dada and tachism, the movement's adherents rejected easel painting and embraced new technological developments, seeking to incorporate time and movement in their works. Fontana's slashed and pierced paintings exemplify his thesis. Arte Povera is an artistic movement that originated in Italy in the 1960s, combining aspects of conceptual, minimalist, and performance art, and making use of worthless or common materials such as earth or newspaper, in the hope of subverting the commercialization of art.

Transavantgarde is the Italian version of Neo-expressionism, an art movement that swept through Italy and the rest of Western Europe in the late 1970s and 1980s. The term transavanguardia was coined by the Italian art critic, Achille Bonito Oliva,[115] originating in the "Aperto '80" at the Venice Biennale,[116][117] and literally means 'beyond the avant-garde'.

Cuisine and meal structure

One of the main characteristics of Italian cuisine is its simplicity, with many dishes made up of few ingredients, and therefore Italian cooks rely on the quality of the ingredients, rather than the complexity of preparation.[128][129] The most popular dishes and recipes, over the centuries, have often been created by ordinary people more so than by chefs, which is why many Italian recipes are suitable for home and daily cooking, respecting regional specificities, privileging only raw materials and ingredients from the region of origin of the dish and preserving its seasonality.[130][131][132]

Italian cuisine has developed through centuries of social and political changes, it has its roots in ancient Rome.

Italian cuisine, like other facets of the culture, speaks with highly inflected regional accents. There are certain self-consciously national constants: spaghetti with tomato sauce and pizza are highly common, but this nationalisation of culinary identity didn't start to take hold until after the Second World War, when southern immigrants flooded to the north in search of work, and even those classics vary from place to place; small enclaves still hold fast to their unique local forms of pasta and particular preparations. Classics such as pasta e fagioli, while found everywhere, are prepared differently according to local traditions. Gastronomic explorations of Italy are best undertaken by knowing the local traditions and eating the local foods.

Northern Italy, mountainous in many parts, is notable for the alpine cheeses of the Valle d'Aosta, the

It is in the food of Naples and Campania, however, that many visitors would recognise the foods that have come to be regarded as quintessentially Italian: pizza, spaghetti with tomato sauce, parmigiana, and so on.

Also, Italy exports and produces the highest level of wine,

The country is also famous for its gelato, or traditional ice-cream often known as Italian ice cream abroad. There are gelaterie or ice-cream vendors and shops all around Italian cities, and it is a very popular dessert or snack, especially during the summer. Sicilian granitas, or a frozen dessert of flavoured crushed ice, more or less similar to a sorbet or a snow cone, are popular desserts not only in Sicily or their native towns of Messina and Catania, but all over Italy (although the northern and central Italian equivalent, grattachecca, commonly found in Rome or Milan, is slightly different from the traditional granita siciliana). Italy also boasts an assortment of desserts.

Christmas in Italy (Italian: Natale, Italian: [naˈtaːle]) begins on 8 December, with the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, the day on which traditionally the Christmas tree is mounted and ends on 6 January, of the following year with the Epiphany (Italian: Epifania, Italian: [epifaˈniːa]).[141] The Christmas cakes pandoro and panettone are popular in the north (pandoro is from Verona, whilst panettone is from Milan); however, they have also become popular desserts in other parts of Italy and abroad. Colomba pasquale is eaten all over the country on Easter day, and is a more traditional alternative to chocolate easter eggs. Tiramisu is a very popular and iconic Italian dessert from Veneto which has become famous worldwide. Other Italian cakes and sweets include cannoli, cassata, fruit-shaped marzipans, and panna cotta.

Coffee, and more specifically

Milan is home to the oldest restaurant in Italy and the second in Europe, the Antica trattoria Bagutto, which has existed since at least 1284.[142]

Italian cuisine is one of the most popular and copied around the world.

Education

Education in Italy is free and mandatory from ages six to sixteen,

Primary education lasts eight years. Students are given a basic education in Italian, English, mathematics, natural sciences, history, geography, social studies, physical education, and visual and musical arts. Secondary education lasts for five years and includes three traditional types of schools focused on different academic levels: the liceo prepares students for university studies with a classical or scientific curriculum, while the istituto tecnico and the istituto professionale prepare pupils for vocational education.

In 2018, the Italian secondary education was evaluated as below the OECD average.[156] Italy scored below the OECD average in reading and science, and near OECD average in mathematics.[156] Trento and Bolzano scored at an above the national average in reading.[156] A wide gap exists between northern schools, which perform near average, and schools in the south, that had much poorer results.[157]

Tertiary education in Italy is divided between

Milan's Bocconi University has been ranked among the top 20 best business schools in the world by The Wall Street Journal international rankings, especially thanks to its Master of Business Administration program, which in 2007 placed it no. 17 in the world in terms of graduate recruitment preference by major multinational companies.[169] In addition, Forbes has ranked Bocconi no. 1 worldwide in the specific category Value for Money.[170] In May 2008, Bocconi overtook several traditionally top global business schools in the Financial Times executive education ranking, reaching no. 5 in Europe and no. 15 in the world.[171] Other top universities and polytechnics include the Polytechnic University of Milan and Polytechnic University of Turin.

In 2009, an Italian research ranked the

Folklore and mythology

In Italian folklore, the

The

An

Alberto da Giussano is a legendary character of the 12th century who would have participated, as a protagonist, in the battle of Legnano on 29 May 1176.[178] In reality, according to historians, the actual military leader of the Lombard League in the famous military battle with Frederick Barbarossa was Guido da Landriano.[179] Historical analyses made over time have indeed shown that the figure of Alberto da Giussano never existed.[180] In the past, historians, attempting to find a real confirmation, hypothesized the identification of his figure with Albertus de Carathe (Alberto da Carate) and Albertus Longus (Alberto Longo), both among the Milanese who signed the pact in Cremona in March 1167 which established the Lombard League, or in an Alberto da Giussano mentioned in an appeal of 1196 presented to Pope Celestine III on the administration of the church-hospital of San Sempliciano. These, however, are all weak identifications, given that they lack clear and convincing historical confirmation.[178][181]

The

Italophilia

Ancient Italy is identified with Rome and the so-called Romanophilia. Despite the fall of the Roman Empire, its legacy continued to have a significant impact on the cultural and political life in Europe. For the medieval mind, Rome came to constitute a central dimension of the European traditionalist sensibility. The idealisation of this Empire as the symbol of universal order led to the construction of the Holy Roman Empire. Writing before the outbreak of the First World War, the historian Alexander Carlyle noted that "we can without difficulty recognize" not only "the survival of the tradition of the ancient empire", but also a "form of the perpetual aspiration to make real the dream of the universal commonwealth of humanity".[183]

During much of the Middle Ages (about the 5th century through the 15th century), the Roman Catholic Church had great political power in Western Europe. Throughout its history, the Catholic faith has inspired many great works of architecture, art, literature, and music. These works include French medieval Gothic cathedrals, the Italian artist Michelangelo's frescoes in the Vatican, the Italian writer Dante's epic poem

As for Italian artists they were in demand almost all over Europe.

The Italian language was fashionable, at court for example, as well as Italian literature and art. The famous lexicographer John Florio of Italian origin was the most important humanist in Renaissance England.[184] and contributed to the English language with over 1,969 words.[185] William Shakespeare's works show an important level of Italophilia, a deep knowledge of Italy and the Italian culture, like in Romeo and Juliet and The Merchant of Venice. According to Robin Kirkpatrick, Professor of Italian and English Literatures at Cambridge University, Shakespeare shared "with his contemporaries and immediate forebears a fascination with Italy".[186] In 16th-century Spain, cultural Italophilia was also widespread (while the Spanish influence in southern Italy was also great) and king Philip IV himself considered Italian as his favourite foreign language.

The movement of "international Italophilia" around 1600 certainly held the German territories in its sway, with one statistic suggesting that up to a third of all books available in Germany in the early 17th century were in Italian.[187] Themes and styles from Il pastor fido were adapted endlessly by German artists, including Opitz, who wrote several poems based on Guarini's text, and Schütz himself, whose settings of a handful of passages appeared in his 1611 book of Italian madrigals. Emperors Ferdinand III and Leopold I were great admirers of Italian culture and made Italian (which they themselves spoke perfectly) a prestigious language at their court. German baroque composers or architects were also very much influenced by their Italian counterparts.

During the 18th century, Italy was in the spotlight of the European grand tour, a period in which learned and wealthy foreign, usually British or German, aristocrats visited the country due to its artistic, cultural and archaeological richness. Since then, throughout the centuries, many writers and poets have sung of Italy's beauty; from

Italiophilia was not uncommon in the United States. Thomas Jefferson was a great admirer of Italy and ancient Rome. Jefferson is largely responsible for the neo-classical buildings in Washington, D.C. that echo Roman and Italian architectural styles.

Spain provided an equally telling example of Italian cultural admiration in the 18th century. The installation of a team of Italian architects and artists, headed by Filippo Juvarra, has been interpreted as part of Queen Elisabeth Farnese's conscious policy to mould the visual culture of the Spanish court along Italian lines. The engagement of Corrado Giaquinto from Molfetta and eventually the Venetian Jacopo Amigoni as the creators of the painted decorative space for the new seat of the Spanish court was a clear indication of this aesthetic orientation, while the later employment of Giovanni Battista Tiepolo and his son Giovanni Domenico confirmed the Italophile tendency.

The Victorian era in Great Britain saw Italophilic tendencies. Britain supported its own version of the imperial Pax Romana, called Pax Britannica. John Ruskin was a Victorian Italophile who respected the concepts of morality held in Italy.[189] Also the writer Henry James has exhibited Italophilia in several of his novels. However, Ellen Moers writes that, "In the history of Victorian Italophilia no name is more prominent than that of Elizabeth Barrett Browning....[She places] Italy as the place for the woman of genius ..."[190]

Italian patriot Giuseppe Garibaldi, along with Giuseppe Mazzini and Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, led the struggle for Italian unification in the 19th century. For his battles on behalf of freedom in Europe and Latin America, Garibaldi has been dubbed the "Hero of Two Worlds". Many of the greatest intellectuals of his time, such as Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, and George Sand showered him with admiration. He was so appreciated in the United States that Abraham Lincoln offered him a command during the Civil War (Garibaldi turned it down).[191]

During the

In 1940 Walt Disney Productions produced Pinocchio based on the Italian children's novel The Adventures of Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi, the most translated non-religious book in the world and one of the best-selling books ever published, as well as a canonical piece of children's literature. The film was the second animated feature film produced by Disney.

After World War II, such brands as

Italian people

The Italian peninsula has been at the heart of Western cultural development at least since Roman times.

Sicilian kings and emperors such as Roger II of Sicily and Frederick II of the Kingdom of Sicily had a significant impact on Italian culture and unified Italy for the first time. No land has made a greater contribution to the visual arts.[196] In the 13th and 14th centuries there were the sculptors Nicola Pisano and his son Giovanni; the painters Cimabue, Duccio, and Giotto; and, later in the period, the sculptor Andrea Pisano. Among the many great artists of the 15th century—the golden age of Florence and Venice—were the architects Filippo Brunelleschi, Lorenzo Ghiberti, and Leon Battista Alberti; the sculptors Donatello, Luca della Robbia, Desiderio da Settignano, and Andrea del Verrocchio; and the painters Fra Angelico, Stefano di Giovanni, Paolo Uccello, Masaccio, Frà Filippo Lippi, Piero della Francesca, Giovanni Bellini, Andrea Mantegna, Antonello da Messina, Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Luca Signorelli, Pietro Perugino, Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, and Vittore Carpaccio.

During the 16th century, the High Renaissance, Rome shared with Florence the leading position in the world of the arts.[196] Major masters included the painter-designer-inventor Leonardo da Vinci; the painter-sculptor-architect Michelangelo Buonarroti; the architects Donato Bramante and Andrea Palladio; the sculptor Benvenuto Cellini; and the painters Titian, Giorgione, Raphael, Andrea del Sarto, and Antonio da Correggio. Among the great painters of the late Renaissance were Tintoretto and Paolo Veronese. Giorgio Vasari was a painter, architect, art historian, and critic.

Among the leading artists of the Baroque period were the sculptors-architects

Music, an integral part of Italian life, owes many of its forms as well as its language to Italy. The inventor of

Composers of the 19th century who made their period the great age of Italian opera were

invented the piano.Italian literature and literary language began with

In philosophy, exploration, and statesmanship, Italy has produced many world-renowned figures: the traveler

The French military and political leader Napoleon was of Italian family and was born in the same year that the Republic of Genoa (former Italian state) ceded the region of Corsica to France.

Notable intellectual and political leaders of more recent times include the Nobel Peace Prize winner in 1907, Ernesto Teodoro Moneta; the sociologist and economist Vilfredo Pareto; the political theorist Gaetano Mosca; the educator Maria Montessori; the philosopher, critic, and historian Benedetto Croce, with his idealistic antagonist Giovanni Gentile; Benito Mussolini, the founder of Fascism and dictator of Italy from 1922 to 1943; Carlo Sforza, Alcide De Gasperi, and Giulio Andreotti, famous latter-day statesmen; and the Communist leaders Antonio Gramsci, Palmiro Togliatti, and Enrico Berlinguer.

Italian scientists and mathematicians of note include Galileo Galilei, Fibonacci, Guglielmo Marconi, Antonio Meucci, Italian-American Enrico Fermi, Gerolamo Cardano, Bonaventura Cavalieri, Evangelista Torricelli, Francesco Maria Grimaldi, Marcello Malpighi, Giuseppe Luigi Lagrangia, Luigi Galvani, Alessandro Volta, Amedeo Avogadro, Stanislao Cannizzaro, Giuseppe Peano, Angelo Secchi, Camillo Golgi, Ettore Majorana, Emilio Segrè, Tullio Levi-Civita, Gregorio Ricci-Curbastro, Daniel Bovet, Giulio Natta, Rita Levi-Montalcini, Italian-American Riccardo Giacconi, and Giorgio Parisi. Elena Cornaro Piscopia was the first female Ph.D. graduate in the world history.

Languages

The Romantic English poet Lord Byron described the Italian language as «that soft bastard Latin, which melts like kisses from a female mouth, and sounds as if it should be writ on satin».[202] Byron's description is not an isolated expression of poetic fancy but, in fact, a popular view of the Italian language across the world, often called the language of "love", "poetry", and "song".[203]

Italian evolved from a

There are only a few communities in Italy in which Italian is not spoken as the first language, but many speakers are native bilinguals of both Italian and Italy's

, and many others.Italian is often natively spoken in a regional variety, not to be confused with Italy's regional and minority languages;[204][205] however, the establishment of a national education system led to a decrease in variation in the languages spoken across the country during the 20th century. Standardisation was further expanded in the 1950s and 1960s due to economic growth and the rise of mass media and television (the state broadcaster RAI helped set a standard Italian).

Libraries and museums

Italy is one of the world's greatest centres of architecture, art, and books. Among its many libraries, the most important are in the national library system, which contains two central libraries, in Florence (5.3 million volumes) and Rome (5 million), and four regional libraries, in Naples (1.8 million volumes), Milan (1 million), Turin (973,000), and Venice (917,000).[206] The existence of two national central libraries, while most nations have one, came about through the history of the country, as Rome was once part of the Papal States and Florence was one of the first capitals of the unified Kingdom of Italy. While both libraries are designated as copyright libraries, Florence now serves as the site designated for the conservation and cataloguing of Italian publications and the site in Rome catalogues foreign publications acquired by the state libraries.[206]

Media

Internet

In 1986, the first internet connection in Italy was experimented in

Currently, Internet access is available to businesses and home users in various forms, including dial-up, cable, DSL, and wireless. The .it is the Internet country code top-level domain (ccTLD) for Italy. The .eu domain is also used, as it is shared with other European Union member states.

According to data released by the fibre-to-the-home (FTTH) Council Europe, Italy represents one of the largest

Figures published by the

Newspapers and periodicals

As of 2002[update], there were about 90 daily newspapers in the country, but not all of them had national circulation.[206] According to Audipress statistics, the major daily newspapers (with their political orientations and estimated circulations) are: la Repubblica, left-wing, 3,276,000 in 2011;[210] Corriere della Sera, independent, 3,274,000 in 2011;[210] La Stampa, liberal, 2,132,000 in 2011;[210] Il Messaggero, left of centre, 1,567,000 in 2011;[210] il Resto del Carlino, right of centre, 1,296,000 in 2011;[210] Il Sole 24 Ore, a financial news paper, 1,015,000 in 2011;[210] il Giornale, independent, 728,000 in 2011;[210] and l'Unità, Communist, 291,000 in 2011.[210] TV Sorrisi e Canzoni is the most popular news weekly with a circulation of 677,658 in July 2012.[211] The periodical press is becoming increasingly important. Among the most important periodicals are the pictorial weeklies—Oggi, L'Europeo, L'Espresso, and Gente. Famiglia Cristiana is a Catholic weekly periodical with a wide readership.

The majority of papers are published in northern and central Italy, and circulation is highest in these areas. Rome and Milan are the most important publication centres. A considerable number of dailies are owned by political parties, the Roman Catholic Church, and various economic groups.[206]

The law provides for freedom of speech and the press, and the government is said to respect these rights in practice.[206]

Radio

Of all the claimants to the title of the "Father of Radio", the one most associated with it is the Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi.[212] He was the first person to send radio communication signals in 1895. By 1899 he flashed the first wireless signal across the English Channel and two years later received the letter "S", telegraphed from England to Newfoundland. This was the first successful transatlantic radiotelegraph message in 1902.

Today, radio waves that are broadcast from thousands of stations, along with waves from other sources, fill the air around us continuously. Italy has three state-controlled radio networks that broadcast day and evening hours on both AM and FM.[nb 1] Program content varies from popular music to lectures, panel discussions, as well as frequent newscasts and feature reports. In addition, many private radio stations mix popular and classical music. A short-wave radio, although unnecessary, aids in the reception of VOA, BBC, Vatican Radio in English and the Armed Forces Network in Germany and in other European stations.

Television

The first form of televised media in Italy was introduced in 1939, when the first experimental broadcasting began. However, this lasted for a very short time: when fascist Italy entered World War II in 1940, all the transmissions were interrupted, and were resumed in earnest only nine years after the end of the conflict, in 1954.

There are two main national television organisations responsible for most viewing: state-owned

The television networks offer varied programs, including news, soap operas, reality TV shows, game shows, sitcoms, cartoons, and films-all in Italian. All programs are in colour, except for the old black-and-white films. Most Italians still depend on VHF/UHF reception, but both cable systems and direct satellite reception is increasingly common. Conventional satellite dishes can pick up European broadcasts, including some in English.

National symbols

National symbols of Italy are the symbols that uniquely identify Italy reflecting its history and culture.[213] They are used to represent the Nation through emblems, metaphors, personifications, and allegories, which are shared by the entire Italian people.

The three main official symbols, are:[214]

- the Constitution of the Italian Republic;[215]

- the emblem of Italy, which is the iconic symbol identifying the Italian Republic;

- The "Il Canto degli Italiani" by Goffredo Mameli and Michele Novaro, the Italian national anthem, which is performed in all public events.

Of these only the flag is explicitly mentioned in the Italian Constitution; this puts the flag under the protection of the law, with criminal penalties for contempt of it.[216]

Other official symbols, as reported by the Presidency of the Italian Republic,[214] are:

- the presidential standard of Italy, that is the distinctive standard representing the Presidency of the Italian Republic;

- the Vittorio Emanuele II of Savoy, the first Sovereign of a united Italy and founder of the Fatherland, which houses the shrine of the Italian tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

- the Festa della Repubblica, which is the national celebratory day established to commemorate the birth of the Italian Republic, which is celebrated every year on 2 June, the date of the institutional referendum of 1946 with which the monarchy was abolished;

The teaching in the schools of the "Il Canto degli Italiani", an account of the

There are also other symbols or emblems of Italy which, although not defined by law, are part of the Italian identity:

- the Italia turrita, which is the national personification of Italy in the appearance of a young woman with her head surrounded by a wall crown completed by towers (hence the term turrita);

- the cockade of Italy, or the national ornament of Italy, obtained by folding a green, white and red ribbon into plissé using the technique called plissage ("pleating");

- the

- the savoy azure has been used or adopted as the colour for many national teams, the first being the men's football team in 1910. The national auto racing colour of Italy is instead rosso corsa (lit. 'racing red'), while in other disciplines such as cycling and winter sports, which often use white.

- the national flower of Italy.[223]

- the national bird of Italy.[224]

- the Graeco-Roman tradition.[225]

- the Frecce Tricolori, or the national aerobatic team of the Italian Air Force.[226]

Public holidays

Public holidays celebrated in Italy include religious, national, and regional observances. Italy's National Day, the

Liberation Day is a national holiday in Italy that commemorates the victory of the Italian resistance movement against Nazi Germany and the Italian Social Republic, puppet state of the Nazis and rump state of the fascists, in the Italian Civil War, a civil war in Italy fought during World War II, which takes place on 25 April. The date was chosen by convention, as it was the day of the year 1945 when the National Liberation Committee of Upper Italy (CLNAI) officially proclaimed the insurgency in a radio announcement, propounding the seizure of power by the CLNAI and proclaiming the death sentence for all fascist leaders (including Benito Mussolini, who was shot three days later).[229]

The

The

The

Religion

In 2017, the proportion of

The

In 2011, minority Christian faiths in Italy included an estimated 1.5 million Orthodox Christians, or 2.5% of the population,

One of the longest-established minority religious faiths in Italy is

Soaring immigration in the last two decades has been accompanied by an increase in non-Christian faiths. Following immigration from the Indian subcontinent, in Italy there are 120,000

The Italian state, as a measure to protect religious freedom, devolves shares of income tax to recognised religious communities, under a regime known as Eight per thousand. Donations are allowed to Christian, Jewish, Buddhist, and Hindu communities; however, Islam remains excluded, since no Muslim communities have yet signed a concordat with the Italian state.[258] Taxpayers who do not wish to fund a religion contribute their share to the state welfare system.[259]

It is noteworthy to pinpoint that owing to the Italian Renaissance, church art in Italy is extraordinary, including works by Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Sandro Botticelli, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Fra Carnevale, Tintoretto, Titian, Raphael, Giotto, and others. Italian church architecture is equally spectacular and historically important to Western culture, notably St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, Cathedral of St. Mark's in Venice, and Brunelleschi's Florence Cathedral, which includes the "Gates of Paradise" doors at the Baptistery by Lorenzo Ghiberti.

Sports

The most popular sport in Italy is football.[260][261] Italy's national football team is one of the world's most successful teams, with four FIFA World Cup victories (1934, 1938, 1982, and 2006).[262] Italian clubs have won 48 major European trophies, making Italy the second most successful country in European football. Italy's top-flight club football league is named Serie A and is followed by millions of fans around the world.[263]

Other popular team sports in Italy include

Italy has a long and successful tradition in individual sports as well.

Historically, Italy has been successful in the Olympic Games, taking part from the first Olympiad and in 47 Games out of 48, not having officially participated in the 1904 Summer Olympics.[276] Italian sportsmen have won 522 medals at the Summer Olympic Games, and another 106 at the Winter Olympic Games, for a combined total of 628 medals with 235 golds, which makes them the fifth most successful nation in Olympic history for total medals. The country hosted two Winter Olympics and will host a third (in 1956, 2006, and 2026), and one Summer games (in 1960).

Traditions

Italian traditions reflect a rich cultural tapestry woven from religious, seasonal, and local celebrations that have evolved over centuries. These traditions blend ancient rituals, religious observances, and local customs, creating a vibrant cultural landscape that varies significantly across different regions of the country.

Religious and seasonal traditions

Christmas and Epiphany

Christmas in Italy is a major holiday beginning on 8 December with the Immaculate Conception and ending on 6 January with the Epiphany.[141] The term Natale derives from Latin, with traditional greetings including buon Natale ('Merry Christmas') and felice Natale ('Happy Christmas').[277]

The

The Epiphany features the Befana, a folkloric figure who brings gifts to children, while Saint Lucy's Day (13 December) is celebrated in some regions as a children's holiday similar to Christmas.

New Year's traditions

New Year's Eve in Italy is marked by traditional rituals, including wearing red underwear and a rarely followed custom of discarding old items by dropping them from windows. Dinner is traditionally shared with family and friends, typically featuring zampone or cotechino with lentils. At 20:30, the president of Italy delivers a television greeting, and at midnight fireworks illuminate the country. A folklore tradition involves eating one spoonful of lentil stew per bell stroke, symbolising good fortune and prosperity.[280]

Local festivals and cultural celebrations

Sagre: local food and cultural festivals

A sagra is a local festival typically celebrating regional cuisine or honouring a patron saint. These festivals often showcase specific local foods, such as the Sagra dell'uva in Marino or the Sagra della Cipolla in Cannara. Common sagre celebrate local products such as olive oil, wine, pasta, chestnuts, and cheese.

Patron saint days and regional festivals

The national patronal day on 4 October honours Saints Francis and Catherine. Each city also celebrates its patron saint's day, such as Rome (Saints Peter and Paul), Milan (Saint Ambrose), and Naples (Saint Januarius). Notable festivals include the Palio di Siena horse race, Holy Week rites, and the Festival of Saint Agatha.

In 2013, UNESCO recognised several Italian festivals as intangible cultural heritage, including the Varia di Palmi and the faradda di li candareri in Sassari. The unique calcio storico fiorentino, an early form of football originating in the Middle Ages, continues to be played annually in Florence.

Carnival traditions

Carnival traditions vary across Italy. In the

Seasonal celebrations

Ferragosto on 15 August marks the peak of the summer vacation period, coinciding with the Assumption of Mary. This tradition exemplifies how religious observances and seasonal celebrations intertwine in Italian culture.

UNESCO World Heritage Sites

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Sites are places of exceptional cultural or natural heritage as defined in the UNESCO World Heritage Convention of 1972.[281] The convention defines cultural heritage as including monuments, architectural works, archaeological sites, and groups of buildings, while natural heritage encompasses geological formations, biological landscapes, and sites of scientific or conservation significance. Italy ratified the convention on 23 June 1978.[282]

The first Italian site, the Rock Drawings in Valcamonica, was listed during the World Heritage Committee's 3rd Session in Cairo and Luxor, Egypt, in 1979.[283] Italy currently holds the world's highest concentration of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. As of 2021[update], Italy has 60 inscribed sites—the most of any country—with 53 cultural and 5 natural sites.[284]

Notable Italian UNESCO World Heritage Sites include significant cultural and natural landmarks such as:

- Archaeological sites:

- Sassi di Matera

- Pompeii, Torre Annunziata, and Herculaneum

- Etruscan necropolises of Cerveteri and Tarquinia

- Architectural marvels:

- Artistic treasures:

- Natural landscapes:

- Historic sites:

- Cinque Terre

- Syracuse and Necropolis of Pantalica

- Val d'Orcia

- Early Christian monuments of Ravenna

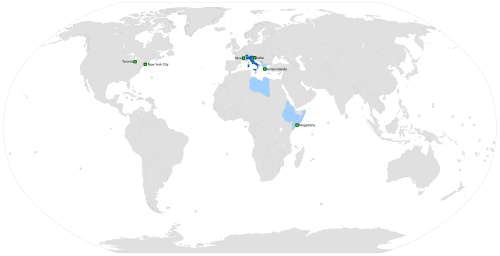

Seven sites are transnational. The Historic Centre of Rome is shared with the Vatican; Monte San Giorgio and the Rhaetian Railway with Switzerland; the Venetian Works of Defence with Croatia and Montenegro; the Prehistoric pile dwellings around the Alps with 5 other countries; the Great Spa Towns of Europe with 6 other countries; and the Ancient and Primeval Beech Forests of the Carpathians and Other Regions of Europe are shared with 17 other countries.[285][286]

See also

Notes

- ^ Rai Radio 1, Rai Radio 2, and Rai Radio 3.

- ^ Rai 1, Rai 2, and Rai 3; Canale 5, Italia 1, and Rete 4.

- Fiume and Zara, passed to Yugoslavia.

- ^ The Holy See's sovereignty has been recognised explicitly in many international agreements and is particularly emphasised in article 2 of the Lateran Treaty of 11 February 1929, in which "Italy recognizes the sovereignty of the Holy See in international matters as an inherent attribute in conformity with its traditions and the requirements of its mission to the world" (Lateran Treaty, English translation).

References

- ^ Cohen, I. Bernard (1965). "Reviewed work: The Scientific Renaissance, 1450-1630, Marie Boas". Isis. 56 (2): 240–42. doi:10.1086/349987. JSTOR 227945.

- ^ Marvin Perry, et al. (2012). Western Civilization: Since 1400. Cengage Learning. p. XXIX. ISBN 978-1-111-83169-1

- ^ Italy has been described as a "cultural superpower" by Arab News, the Washington Post, The Australian, and leaders including the former Foreign Affairs Minister Giulio Terzi di Sant'Agata and U.S. President Barack Obama.

- ^ Kimbell, David R. B. Italian Opera. Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- ^ Zirpolo, Lilian H. The A to Z of Renaissance Art. Scarecrow Press, 2009.

- ISBN 9780199571123.

- ^ Kohle, Hubertus (19 July 2006). "The road from Rome to Paris. The birth of a modern Neoclassicism". archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de.

- ^ Sear, Frank. Roman architecture. Cornell University Press, 1983. p. 10.

- ^ Italy Architecture: Early Christian and Byzantine Archived 28 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Italy Architecture: Romanesque Archived 28 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Campbell, Stephen J; Cole, Michael Wayne (2012). Italian Renaissance Art. Thames & Hudson Inc. pp. 95–97.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the Veneto".

- ^ R. De Fusco, A thousand years of architecture in Europe, p. 443.

- ISBN 9780199571123.

- ^ Kohle, Hubertus (19 July 2006). "The road from Rome to Paris. The birth of a modern Neoclassicism".

- ^ a b "Cinecittà, c'è l'accordo per espandere gli Studios italiani" (in Italian). 30 December 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "L'œuvre cinématographique des frères Lumière - Pays: Italie" (in French). Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "Il Cinema Ritrovato - Italia 1896 - Grand Tour Italiano" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "26 febbraio 1896 - Papa Leone XIII filmato Fratelli Lumière" (in Italian). Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Cinematografia", Dizionario enciclopedico italiano (in Italian), vol. III, Treccani, 1970, p. 226

- ISBN 978-88-06-14528-6.

- ISBN 978-88-6074-066-3.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-0595-4.

- ISBN 978-1-55859-236-0.

- ISBN 978-1-317-65028-7.

- ^ "Il cinema delle avanguardie" (in Italian). 30 September 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Ariston (24 July 2014). "Venice: David Gordon Green's 'Manglehorn,' Abel Ferrara's 'Pasolini' in Competition Lineup". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 18 February 2016.

- ^ "Federico Fellini, i 10 migliori film per conoscere il grande regista" (in Italian). 20 January 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ISBN 978-0060742140

- ISBN 978-88-06-14528-6.

- ^ "The Cinema Under Mussolini". Ccat.sas.upenn.edu. Archived from the original on 31 July 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ^ "STORIA 'POCONORMALE' DEL CINEMA: ITALIA ANNI '80, IL DECLINO" (in Italian). Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "The Bicycle Thief / Bicycle Thieves (1949)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ "The 25 Most Influential Directors of All Time". MovieMaker Magazine. 7 July 2002. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ "Italian Neorealism – Explore – The Criterion Collection". Criterion.com. Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ "Western all'italiana" (in Italian). Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "Tarantino e i film italiani degli anni settanta" (in Italian). Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "Cannes 2013. La grande bellezza". Stanze di Cinema (in Italian). 21 May 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-8264-1247-8.

- ^ "Oscar 2022: Paolo Sorrentino e gli altri candidati come miglior film internazionale" (in Italian). 26 October 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "10 film italiani che hanno fatto la storia del Festival di Cannes" (in Italian). 13 May 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "I film italiani vincitori del Leone d'Oro al Festival di Venezia" (in Italian). 28 August 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "Film italiani vincitori Orso d'Oro di Berlino" (in Italian). Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "Alberto Sordi: "La grande guerra"" (in Italian). Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ "International Journal of Comic Art". s.n. 20 August 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2017 – via Google Books.

- )

- ^ "Welcome to IFAFA". Italian Folk Art Federation of America. Archived from the original on 6 November 2010. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ "New York Takes Top Global Fashion Capital Title from London, edging past Paris". Languagemonitor.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ISBN 978-1-58115-045-2.

- ^ Cardini, Tiziana (28 October 2020). "Get to Know the Young Winners of the 2020 International Talent Support Awards". Vogue.

- ^ Miller (2005) p. 486. Web. 26 September 2011.

- ^ a b c Insight Guides (2004) p. 220. 26 September 2011.

- ^ a b Insight Guides (2004) p.220

- ^ "Wiley: Design City Milan - Cecilia Bolognesi". Wiley.com. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ "Frieze Magazine - Archive - Milan and Turin". Frieze.com. 10 January 2010. Archived from the original on 10 January 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ ISBN 9780151957477. See also Western canonfor other "canons" that include the Divine Comedy.

- ^ Duckworth, George Eckel. The nature of Roman comedy: a study in popular entertainment. University of Oklahoma Press, 1994. p. 3. Web. 15 October 2011.

- ISBN 978-1-61530-490-5. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-521-66622-0. Archivedfrom the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ Ernest Hatch Wilkins, The invention of the sonnet, and other studies in Italian literature (Rome: Edizioni di Storia e letteratura, 1959), 11–39

- ^ "Giovanni Boccaccio: The Decameron.". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Alessandro Manzoni | Italian author". Encyclopedia Britannica. 18 May 2023.

- ISBN 0-8057-0950-9, p. 38.

- ^ Bottigheimer 2012a, 7; Waters 1894, xii; Zipes 2015, 599.

- ISBN 978-0-19-211559-1

- ^ "I Promessi sposi or The Betrothed". Archived from the original on 18 July 2011.

- ISBN 978-1-135-45530-9.

- ISBN 88-343-4889-3

- ISBN 978-0-7148-3542-6.

- ^ "All Nobel Prizes in Literature". Nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 29 May 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-19-816171-4.

- ^ Allen, Edward Heron (1914). Violin-making, as it was and is: Being a Historical, Theoretical, and Practical Treatise on the Science and Art of Violin-making, for the Use of Violin Makers and Players, Amateur and Professional. Preceded by An Essay on the Violin and Its Position as a Musical Instrument. E. Howe. Accessed 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b c "The Theatre and its history". Teatro di San Carlo's official website. 23 December 2013.

- ^ "Obituary: Luciano Pavarotti". The Times. London. 6 September 2007. Archived from the original on 25 July 2008.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-46643-1. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-351-54426-9.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (3 October 2012). "A Roman Rapper Comes to New York, Where He Can Get Real". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ a b "This record was a collaboration between Philip Oakey, the big-voiced lead singer of the techno-pop band the Human League, and Giorgio Moroder, the Italian-born father of disco who spent the '80s writing synth-based pop and film music." Evan Cater. "Philip Oakey & Giorgio Moroder: Overview". AllMusic. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- ^ McDonnell, John (1 September 2008). "Scene and heard: Italo-disco". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ^ Yiorgos Kasapoglou (27 February 2007). "Sanremo Music Festival kicks off tonight". www.esctoday.com. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ Lomax, Alan (1956). "Folk Song Style: Notes on a Systematic Approach to the Study of Folk Song." Journal of the International Folk Music Council, VIII, pp. 48–50.

- ^ ISBN 9789042023215.

- ^ Herodotus. The Histories. Penguin Classics. p. 226.

- ^ "St. Thomas Aquinas | Biography, Philosophy, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ISBN 0-801-48785-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-1904380634.

- ^ a b "Introduction to Montessori Method". American Montessori Society.

- ^ Blair, Peter. "Reason and Faith: The Thought of Thomas Aquinas". The Dartmouth Apologia. Archived from the original on 13 September 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ Moschovitis Group Inc, Christian D. Von Dehsen and Scott L. Harris, Philosophers and religious leaders (The Oryx Press, 1999), 117.

- ^ a b c "The Enlightenment throughout Europe". history-world.org. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ a b c "History of Philosophy 70". maritain.nd.edu. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- S2CID 147563567.

- ^ Pernicone, Nunzio (2009). Italian Anarchism 1864–1892. AK Press. pp. 111–113.

- ISBN 88-07-81462-5.

- ^ Bergin, Thomas Goddard; Speake, Jennifer. Encyclopedia of The Renaissance and the Reformation. Infobase Publishing, 2004. pp. 144-145. Web. 10 November 2012.

- ^ Ciuccetti, Laura. Michelangelo: David. Giunti Editore, 1998. p. 24. Web. 16 November 2012.

- ^ Duiker, William J.; Spielvogel, Jackson J. World History. Cengage Learning, 2008. pp. 450-451. Web. 10 November 2012.

- ^ "Storia del Teatro nelle città d'Italia" (in Italian). Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ "Storia del teatro: lo spazio scenico in Toscana" (in Italian). Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ISBN 978-8879839747.

- ISBN 978-8879839747.

- ISBN 978-0-415-74506-2.

- ISBN 978-90-420-1798-6.

- ISBN 041-520-408-9.

- ^ "Compagnia dei Gelosi". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ISBN 0-413-73320-3.

- ISBN 9780739151112.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1997". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ISBN 91-7324-602-6.

- ^ "The Ballet". metmuseum.org. October 2004.

- ^ "Andros on Ballet – Catherine Medici De". michaelminn.net. Archived from the original on 9 February 2008.

- ^ Kuzmick Hansell, Kathleen (1980). Opera and Ballet at the Regio Ducal Teatro of Milan, 1771-1776: A Musical and Social History. Vol. I. University of California. p. 200.[ISBN unspecified]

- ^ "Roman Painting". art-and-archaeology.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Roman Wall Painting". accd.edu. Archived from the original on 19 March 2007.

- ^ Chilvers, Ian (1999). A Dictionary of Twentieth-Century Art. Oxford University Press. p. 620. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Nieves, Marysol (2011). Taking Aim! The Business of Being An Artist Today. Fordham University Press. p. 236. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ "The 1980s". La Biennale. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ISBN 978-0140273281.

- ^ "Italian Food". Life in Italy. Archived from the original on 8 May 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ "The History of Italian Cuisine I". Life in Italy. 30 October 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ Thoms, Ulrike. "From Migrant Food to Lifestyle Cooking: The Career of Italian Cuisine in Europe Italian Cuisine". EGO (European History Online). Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Related Articles (2 January 2009). "Italian cuisine". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Britannica.com. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ "Italian Food – Italy's Regional Dishes & Cuisine". Indigo Guide. Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ "Regional Italian Cuisine". Rusticocooking.com. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ "Cronistoria della cucina italiana" (in Italian). Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ "Piatti regionali a diffusione nazionale" (in Italian). Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Freeman, Nancy (2 March 2007). "American Food, Cuisine". Sallybernstein.com. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ "Intervista esclusiva allo chef Carlo Cracco: "La cucina è cultura"" (in Italian). Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Storia della cucina italiana: le tappe della nostra cultura culinaria" (in Italian). 25 May 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Individualità territoriale e stagionalità nella cucina italiana" (in Italian). Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Regole e stagionalità della cucina italiana" (in Italian). 2 December 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Nonne come chef" (in Italian). Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ a b Creasy, Rosalind. The edible Italian garden. Periplus, 1999. p. 57. Web. 27 November 2013.

- ^ Del Conte, 11-21.

- ISBN 978-1-84537-989-6. Archived from the originalon 16 June 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "Qual è il caffè espresso perfetto e come va bevuto?" (in Italian). Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ "FAOSTAT". faostat.fao.org. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ "FAOSTAT". faostat.fao.org. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ Mulligan, Mary Ewing; McCarthy, Ed. Italy: A passion for wine. 2006, 62(7), 21-27. Web. 27 September 2011.

- ^ "Wine". Unrv.com. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ a b "The Best Christmas Traditions in Italy". Walks of Italy. 25 November 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Antica trattoria Bagutto" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ "Mangiare all'italiana" (in Italian). Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Colazioni da incubo in giro per il mondo" (in Italian). 29 March 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Merenda, una abitudine tutta italiana: cinque ricette salutari per tutta la famiglia" (in Italian). 12 August 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "How pasta became the world's favourite food". bbc. 15 June 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Devorah, Lev-Tov. "What Is Sicilian Pizza?". The Spruce Eats. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ "I finti prodotti italiani? Anche in Italia!" (in Italian). 4 February 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ "In cosa consiste l'Italian Sounding" (in Italian). 25 March 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ "Number of Michelin-starred restaurants in Italy in 2024, by region" (in Italian). Retrieved 20 November 2024.

- ^ "Michelin Guide 2024 - Italy - Two new 3 Michelin stars restaurants". Retrieved 20 November 2024.

- ^ "Law 27 December 2007, n.296". Italian Parliament. Archived from the original on 6 December 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ "| Human Development Reports" (PDF). Hdr.undp.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ISBN 88-02-03568-7.

- ISBN 978-8880828419.

- ^ a b c "PISA 2018 results". www.oecd.org. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ "The literacy divide: territorial differences in the Italian education system" (PDF). Parthenope University of Naples. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ^ "Number of top-ranked universities by country in Europe". jakubmarian.com. 2019.

- ^ Top Universities Archived 17 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine World University Rankings Retrieved 6 January 2010

- ISBN 978-1-57922-366-3. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ISBN 0-7864-3462-7, p. 55f.

- ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. 47–55.

- ^ "Censis, la classifica delle università: Bologna ancora prima". 3 July 2017.

- ^ "Chi siamo - Sapienza - Università di Roma". Uniroma1.it. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ "Sapienza among Top World Universities - Sapienza - Università di Roma". en.uniroma1.it. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities - 2012 - Top 500 universities - Shanghai Ranking - 2012 - World University Ranking - 2012". Shanghairanking.com. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ "Europe - Ranking Web of Universities". Webometrics.info. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ "Center for World University Rankings". Cwur.org/top100.html. 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ (in Italian) Un caloroso benvenuto agli MBA 33 in aula per i precorsi. Archived 9 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine Master of Business Administration a Milano, Italia - MBA SDA Bocconi. Web. 31 January 2011.

- ^ "Programs > Brochure > Penn Abroad". Archived from the original on 16 June 2010. Retrieved 27 September 2011. Bocconi Università in Milan (BMI). Penn Abroad. 27 September 2011.

- ^ (in Italian) Sda Bocconi supera London Business School. Corriere della Sera. Web. 31 January 2011.

- ^ (in Italian) Le Università Italiane ed Europee nel mercato globale dell'innovazione - Conferenza annuale. Archived 24 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine Vision the Italian Think Tank. Web. 31 January 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-06-135024-5.

- ^ "Viva La Befana". Transparent Language 6 Jan 2009. 12 Dec 2009.

- ^ a b "Italian Christmas tradition of "La Befana"." Italian-Link.com n.d. 15 Dec 2009

- ^ "Festa del Badalisc ad Andrista (località di Cevo)" (in Italian). Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- Critique of Judgement, Book II, "Analytic of the Sublime", Simon and Schuster: "In my part of the country, if you set a common man a problem like that of Columbus and his egg, he says, 'There is no art in that, it is only science': i.e. you can do it if you know how; and he says just the same of all the would-be arts of jugglers."

- ^ a b Alberto da Giussano entry (in Italian) in the Enciclopedia Treccani

- ISBN 978-88-420-9243-8.

- ISBN 978-88-420-9243-8.

- ^ Alberto da Giussano entry (in Italian) in the Enciclopedia Treccani

- ^ Rengel, Marian; Daly, Kathleen N. (2009). Greek and Roman Mythology, A to Z. United States: Facts On File, Incorporated. p. 66.

- ^ Jameson, John Franklin; Bourne, Henry Eldridge; Schuyler, Robert Livingston. The American Historical Review. (Full text) American Historical Association, 1914. Web. 09. Dec. 2013.

- ^ Simonini, R. C. (1952). Italian Scholarship in Renaissance England. University of North Carolina Studies in Comparative Literature. Vol. 3. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina. p. 68.

- ^ Empire of Words: The Reign of the OED, by John Willinsky, Princeton University Press, 1994

- ^ Kirkpatrick, Robin. English and Italian literature from Dante to Shakespeare: a study of sources, analogue and divergence. Longman, 1995. p. 278. Web. 22 November 2013.

- Mikulás̆ Teich, ed., The Renaissance in National Context. Cambridge University Press, 1992. p. 13. Web. 21 November 2013.

- ^ Shelley, Percy Bysshe. The Narrative Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley (Volume 1). Wildside Press LLC, 2008. p. 27. Web. 21 November 2013.

- ^ Wilson, A.N. The Victorians. Random House, 2011. p. 86. Web. 23 November 2013.

- ^ Mahkovec, Linda. Voicing Female Ambition and Purpose: The Role of the Artist Figure in the Works of George Eliot. ProQuest, 2008. p. 33. Web. 23 November 2013.

- ^ Appy, Christian G. Cold War Constructions: The Political Culture of United States Imperialism, 1945-1966. University of Massachusetts Press, 2000. p. 108. Web. 24 November 2013.

- ^ Keegan, John. The Mask Of Command: A Study of Generalship. Random House, 2011. p. 281. Web. 2 December 2013.

"[A]s I walked with [the Duce] in the gardens of the Villa Borghese, I could easily compare his profile with that of the Roman busts, and I realised he was one of the Caesars." - ^ Trevor-Roper, Hugh. Hitler's Table Talk 1941-1944: Secret Conversations. Enigma Books, 2013. p. 203. Web. 23 November 2013.

- ^ a b Carruthers, Bob. Hitler's Wartime Conversations. His Personal Thoughts as Recorded by Martin Bormann. Pen & Sword Books, 2018. Web. 21 February 2022.

- ^ Fisher, Ian. Italy (Background). The New York Times. Web. 1 December 2013.

"Encyclopædia Britannica describes Italy as "less a single nation than a collection of culturally related points in an uncommonly pleasing setting". However concise, this description provides a good starting point for the difficult job of defining Italy, a complex nation wrapped in as much myth and romance as its own long-documented history. The uncommonly pleasant setting is clear: the territory on a boot-shaped peninsula in the Mediterranean, both mountainous and blessed with 4,600 miles [7,400 kilometres] of coast. The culturally related points include many of the fountains of Western culture: the Roman Empire, the Catholic church, the Renaissance (not to mention pasta and pizza)."

"It has been central to the formation of the European Union, and after the destruction of World War II, built itself with uncommon energy to regain a place in the global economy." - ^ a b c d Worldmark encyclopedia of the nations. Gale Research, 1995. p. 241. Web. 17 July 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4. (subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membershiprequired)

- ^ Weissmüller, Alberto. Palladio in Venice. Grafiche Vianello srl, 2005. p. 127. Web. 12 December 2013.

- ^ "Enrico Fermi, architect of the nuclear age, dies". Autumn 1954. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ "Enrico Fermi Dead at 53; Architect of Atomic Bomb". The New York Times. 29 November 1954. Archived from the original on 14 March 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ McLynn, Frank (1998). Napoleon. Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6247-5. ASIN 0712662472.

- ISBN 9788807948213.

- ^ Clivio, Gianrenzo P.; Danesi, Marcel. The Sounds, Forms, and Uses of Italian. University of Toronto Press, 2000. p. 3. Web. 31 October 2012.

- ^ "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in danger". www.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 18 December 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Italian language". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 November 2008. Archived from the original on 29 November 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4144-1089-0. Retrieved 10 February 2025.

- ^ The University of Pisa celebrates 25 years of being on the net. Università degli Studi di Pisa. Web. 1 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d Will Italy have the best FTTH network in Europe? Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine FTTH Council Europe. Web. 2 December 2012.