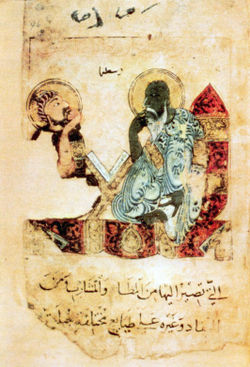

Averroes

Averroes Ibn Rushd | |

|---|---|

| ابن رشد | |

unity of the intellect |

Ibn Rushd

Averroes was a strong proponent of

His legacy in the

Name

Ibn Rushd's full, transliterated Arabic name is "Abū l-Walīd Muḥammad ibn ʾAḥmad Ibn Rushd".[5][6] Sometimes, the nickname al-Hafid ("The Grandson") is appended to his name, to distinguish him from his grandfather, a famous judge and jurist.[7] "Averroes" is the Medieval Latin form of "Ibn Rushd"; it was derived from the Spanish pronunciation of the original Arabic name, wherein "Ibn" becomes "Aben" or "Aven".[8] Other forms of the name in European languages include "Ibin-Ros-din", "Filius Rosadis", "Ibn-Rusid", "Ben-Raxid", "Ibn-Ruschod", "Den-Resched", "Aben-Rassad", "Aben-Rasd", "Aben-Rust", "Avenrosdy", "Avenryz", "Adveroys", "Benroist", "Avenroyth" and "Averroysta".[8]

Biography

Early life and education

Little is known about Averroes's early life.

According to his traditional biographers, Averroes's education was "excellent",

Career

By 1153 Averroes was in Marrakesh, the capital of the Almohad Caliphate (now in Morocco), to perform astronomical observations and to support the Almohad project of building new colleges.[16][17] He was hoping to find physical laws of astronomical movements instead of only the mathematical laws known at the time but this research was unsuccessful.[17] During his stay in Marrakesh, he likely met ibn Tufayl, a renowned philosopher and the author of Hayy ibn Yaqdhan who was also the court physician in Marrakesh.[14][17] Averroes and ibn Tufayl became friends despite the differences in their philosophies.[14][18]

In 1169, ibn Tufayl introduced Averroes to the Almohad caliph Abu Yaqub Yusuf.[17][19] In a famous account reported by historian 'Abd al-Wahid al-Marrakushi, the caliph asked Averroes whether the heavens had existed since eternity or had a beginning.[17][19] Knowing this question was controversial and worried a wrong answer could put him in danger, Averroes did not answer.[19] The caliph then elaborated the views of Plato, Aristotle and Muslim philosophers on the topic and discussed them with Ibn Tufayl.[17][19] This display of knowledge put Averroes at ease; Averroes then explained his views on the subject, which impressed the caliph.[17] Averroes was similarly impressed by Abu Yaqub and later said the caliph had "a profuseness of learning I did not suspect".[19]

After their introduction, Averroes remained in Abu Yaqub's favor until the caliph died in 1184.[17] When the caliph complained to Ibn Tufayl about the difficulty of understanding Aristotle's work, Ibn Tufayl recommended to the caliph that Averroes work on explaining it.[17][19] This was the beginning of Averroes's massive commentaries on Aristotle;[19] his first works on the subject were written in 1169.[19]

In the same year, Averroes was appointed qadi (judge) in Seville.[17][20] In 1171 he became qadi in his hometown of Córdoba.[15][17] As qadi he would decide cases and give fatwas (legal opinions) based on religious law.[20] The writing rate increased during this time despite other obligations and his travels within the Almohad empire.[17] He also took the opportunity from his travels to conduct astronomical research.[16] Many of his works produced between 1169 and 1179 were dated in Seville rather than Córdoba.[17] In 1179 he was again appointed qadi in Seville.[15] In 1182, he succeeded his friend Ibn Tufayl as court physician. Later the same year, he was appointed chief qadi of Córdoba, then controlled by the Taifa of Seville, a prestigious office that his grandfather had once held.[17][20]

In 1184 Caliph Abu Yaqub died and was succeeded by Abu Yusuf Yaqub.[17] Initially, Averroes remained in royal favour, but in 1195, his fortune reversed.[17][19] Various charges were made against him, and a tribunal in Córdoba tried him.[17][19] The tribunal condemned his teachings, ordered the burning of his works and banished Averroes to nearby Lucena.[17] Early biographers' reasons for this fall from grace include a possible insult to the caliph in his writings[19] but modern scholars attribute it to political reasons. The Encyclopaedia of Islam said the caliph distanced himself from Averroes to gain support from more orthodox ulema, who opposed Averroes and whose support al-Mansur needed for his war against Christian kingdoms.[17] Historian of Islamic philosophy Majid Fakhry also wrote that public pressure from traditional Maliki jurists who were opposed to Averroes played a role.[19]

After a few years, Averroes returned to court in Marrakesh and was again in the caliph's favor.[17] He died shortly afterwards, on 11 December 1198 (9 Safar 595 in the Islamic calendar).[17] He was initially buried in North Africa. His body was later moved to Córdoba for another funeral, at which future Sufi mystic and philosopher ibn Arabi (1165–1240) was present.[17]

Works

Averroes was a prolific writer and his works, according to Fakhry, "covered a greater variety of subjects" than those of any of his predecessors in the East, including philosophy, medicine, jurisprudence or legal theory, and linguistics.

Commentaries on Aristotle

Averroes wrote commentaries on nearly all of Aristotle's surviving works.[21] The only exception is Politics, which he did not have access to, so he wrote commentaries on Plato's Republic.[21] He classified his commentaries into three categories that modern scholars have named short, middle and long commentaries.[25] Most of the short commentaries (jami) were written early in his career and contain summaries of Aristotlean doctrines.[22] The middle commentaries (talkhis) contain paraphrases that clarify and simplify Aristotle's original text.[22] The middle commentaries were probably written in response to his patron caliph Abu Yaqub Yusuf's complaints about the difficulty of understanding Aristotle's original texts and to help others in a similar position.[22][25] The long commentaries (tafsir or sharh), or line-by-line commentaries, include the complete text of the original works with a detailed analysis of each line.[26] The long commentaries are very detailed and contain a high degree of original thought,[22] and were unlikely to be intended for a general audience.[25] Only five of Aristotle's works had all three types of commentaries: Physics, Metaphysics, On the Soul, On the Heavens, and Posterior Analytics.[21]

Stand-alone philosophical works

Averroes also wrote stand-alone philosophical treatises, including On the Intellect, On the Syllogism, On Conjunction with the Active Intellect, On Time, On the Heavenly Sphere and On the Motion of the Sphere. He also wrote several

Islamic theology

Scholarly sources, including Fakhry and the Encyclopaedia of Islam, have named three works Averroes's critical writings in this area. Fasl al-Maqal ("The Decisive Treatise") is an 1178 treatise that argues for the compatibility of Islam and philosophy.[27] Al-Kashf 'an Manahij al-Adillah ("Exposition of the Methods of Proof"), written in 1179, criticizes the theologies of the Ash'arites,[28] and lays out Averroes's argument for proving the existence of God, as well as his thoughts on God's attributes and actions.[29] The 1180 Tahafut at-Tahafut ("Incoherence of the Incoherence") is a rebuttal of al-Ghazali's (d. 1111) landmark criticism of philosophy The Incoherence of the Philosophers. It combines ideas in his commentaries and stand-alone works and uses them to respond to al-Ghazali.[30] The work also criticizes Avicenna and his neoplatonist tendencies, sometimes agreeing with al-Ghazali's critique against him.[30]

Medicine

Averroes, who served as the royal physician at the Almohad court, wrote a number of medical treatises. The most famous was al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb ("The General Principles of Medicine", Latinized in the west as the Colliget), written around 1162, before his appointment at court.[31] The title of this book is the opposite of al-Juz'iyyat fi al-Tibb ("The Specificities of Medicine"), written by his friend Ibn Zuhr, and the two collaborated intending that their works complement each other.[32] The Latin translation of the Colliget became a medical textbook in Europe for centuries.[31] His other surviving titles include On Treacle, The Differences in Temperament, and Medicinal Herbs.[33] He also wrote summaries of the works of Greek physician Galen (died c. 210) and a commentary on Avicenna's Urjuzah fi al-Tibb ("Poem on Medicine").[31]

Jurisprudence and law

Averroes served multiple tenures as judge and produced multiple works in the fields of Islamic jurisprudence or legal theory. The only book that survives today is Bidāyat al-Mujtahid wa Nihāyat al-Muqtaṣid ("Primer of the Discretionary Scholar").

Philosophical ideas

Aristotelianism in the Islamic philosophical tradition

In his philosophical writings, Averroes attempted to return to Aristotelianism, which according to him had been distorted by the Neoplatonist tendencies of Muslim philosophers such as Al-Farabi and Avicenna.[37][38] He rejected al-Farabi's attempt to merge the ideas of Plato and Aristotle, pointing out the differences between the two, such as Aristotle's rejection of Plato's theory of ideas.[39] He also criticized Al-Farabi's works on logic for misinterpreting its Aristotelian source.[40] He wrote an extensive critique of Avicenna, who was the standard-bearer of Islamic Neoplatonism in the Middle Ages.[41] He argued that Avicenna's theory of emanation had many fallacies and was not found in the works of Aristotle.[41] Averroes disagreed with Avicenna's view that existence is merely an accident added to essence, arguing the reverse; something exists per se and essence can only be found by subsequent abstraction.[42] He also rejected Avicenna's modality and Avicenna's argument to prove the existence of God as the Necessary Existent.[43]

Averroes felt strongly about the incorporation of Greek thought into the Muslim world, and wrote that "if before us someone has inquired into [wisdom], it behooves us to seek help from what he has said. It is irrelevant whether he belongs to our community or to another".[44]

Relation between religion and philosophy

During Averroes's lifetime, philosophy came under attack from the Sunni tradition, especially from theological schools like the Hanbali school and the Ashʾarites.[45] In particular, the Ashʾari scholar al-Ghazali (1058–1111) wrote The Incoherence of the Philosophers, a scathing and influential critique of the Neoplatonic philosophical tradition in the Islamic world and against the works of Avicenna in particular.[46] Among others, Al-Ghazali charged philosophers with non-belief in Islam and sought to disprove the teaching of the philosophers using logical arguments.[45][47]

In Decisive Treatise, Averroes argues that philosophy—which for him represented conclusions reached using reason and careful method—cannot contradict revelations in Islam because they are just two different methods of reaching the truth, and "truth cannot contradict truth".[48][49] When conclusions reached by philosophy appear to contradict the text of the revelation, then according to Averroes, revelation must be subjected to interpretation or allegorical understanding to remove the contradiction.[45][48] This interpretation must be done by those "rooted in knowledge"—a phrase taken from surah Āl Imrān 3:7 of the Quran, which for Averroes refers to philosophers who during his lifetime had access to the "highest methods of knowledge".[48][49] He also argues that the Quran calls for Muslims to study philosophy because the study and reflection of nature would increase a person's knowledge of "the Artisan" (God).[50] He quotes Quranic passages calling Muslims to reflect on nature. He uses them to render a fatwa that philosophy is allowed for Muslims and is probably an obligation, at least among those who have the talent for it.[51]

Averroes also distinguishes between three modes of discourse: the rhetorical (based on persuasion) accessible to the common masses; the dialectical (based on debate) and often employed by theologians and the ulama (religious scholars); and the demonstrative (based on logical deduction).[45][50] According to Averroes, the Quran uses the rhetorical method of inviting people to the truth, which allows it to reach the common masses with its persuasiveness,[52] whereas philosophy uses the demonstrative methods that were only available to the learned but provided the best possible understanding and knowledge.[52]

Averroes also tries to deflect Al-Ghazali's criticisms of philosophy by saying that many of them apply only to the philosophy of Avicenna and not to that of Aristotle, which Averroes argues to be the true philosophy from which Avicenna has deviated.[53]

Nature of God

Existence

Averroes lays out his views on the existence and nature of God in the treatise The Exposition of the Methods of Proof.

God's attributes

Averroes upholds the doctrine of divine unity (tawhid) and argues that God has seven divine attributes: knowledge, life, power, will, hearing, vision and speech. He devotes the most attention to the attribute of knowledge and argues that divine knowledge differs from human knowledge because God knows the universe because God is its cause while humans only know the universe through its effects.[54]

Averroes argues that the attribute of life can be inferred because it is the precondition of knowledge and also because God willed objects into being.[58] Power can be inferred by God's ability to bring creations into existence. Averroes also argues that knowledge and power inevitably give rise to speech. Regarding vision and speech, he says that because God created the world, he necessarily knows every part of it in the same way an artist understands his or her work intimately. Because two elements of the world are the visual and the auditory, God must necessarily possess vision and speech.[54]

The omnipotence paradox was first addressed by Averroes[59] and only later by Thomas Aquinas.[60]

Pre-eternity of the world

In the centuries preceding Averroes, there had been a debate between Muslim thinkers questioning whether the world was created at a specific moment in time or whether it has

Averroes responded to Al-Ghazali in his Incoherence of the Incoherence. He argued first that the differences between the two positions were not vast enough to warrant the charge of unbelief.[62] He also said the pre-eternity doctrine did not necessarily contradict the Quran and cited verses that mention pre-existing "throne" and "water" in passages related to creation.[63][64] Averroes argued that a careful reading of the Quran implied only the "form" of the universe was created in time but that its existence has been eternal.[63] Averroes further criticized the mutakallimin for using their interpretations of scripture to answer questions that should have been left to philosophers.[65]

Politics

Averroes states his political philosophy in his commentary of Plato's Republic. He combines his ideas with Plato's and with Islamic tradition; he considers the ideal state to be one based on the Islamic law (

According to Averroes, there are two methods of teaching virtue to citizens; persuasion and coercion.[68] Persuasion is the more natural method consisting of rhetorical, dialectical and demonstrative methods; sometimes, however, coercion is necessary for those not amenable to persuasion, e.g. enemies of the state.[68] Therefore, he justifies war as a last resort, which he also supports using Quranic arguments.[68] Consequently, he argues that a ruler should have both wisdom and courage, which are needed for governance and defense of the state.[69]

Like Plato, Averroes calls for women to share with men in the administration of the state, including participating as soldiers, philosophers and rulers.[70] He regrets that contemporaneous Muslim societies limited the public role of women; he says this limitation is harmful to the state's well-being.[66]

Averroes also accepted Plato's ideas of the deterioration of the ideal state. He cites examples from Islamic history when the

Diversity of Islamic law

In his tenure as judge and jurist, Averroes for the most part ruled and gave fatwas according to the Maliki school of Islamic law which was dominant in Al-Andalus and the western Islamic world during his time.[72] However, he frequently acted as "his own man", including sometimes rejecting the "consensus of the people of Medina" argument that is one of the traditional Maliki position.[73] In Bidāyat al-Mujtahid, one of his major contributions to the field of Islamic law, he not only describes the differences between various school of Islamic laws but also tries to theoretically explain the reasons for the difference and why they are inevitable.[74] Even though all the schools of Islamic law are ultimately rooted in the Quran and hadith, there are "causes that necessitate differences" (al-asbab al-lati awjabat al-ikhtilaf).[75][76] They include differences in interpreting scripture in a general or specific sense,[77] in interpreting scriptural commands as obligatory or merely recommended, or prohibitions as discouragement or total prohibition,[78] as well as ambiguities in the meaning of words or expressions.[79] Averroes also writes that the application of qiyas (reasoning by analogy) could give rise to different legal opinion because jurists might disagree on the applicability of certain analogies[80] and different analogies might contradict each other.[81][82]

Natural philosophy

Astronomy

As did

Averroes was aware that Arabic and Andalusian astronomers of his time focused on "mathematical" astronomy, which enabled accurate predictions through calculations but did not provide a detailed physical explanation of how the universe worked.[87] According to him, "the astronomy of our time offers no truth, but only agrees with the calculations and not with what exists."[88] He attempted to reform astronomy to be reconciled with physics, especially the physics of Aristotle. His long commentary of Aristotle's Metaphysics describes the principles of his attempted reform, but later in his life he declared that his attempts had failed.[17][83] He confessed that he had not enough time or knowledge to reconcile the observed planetary motions with Aristotelian principles.[83] In addition, he did not know the works of Eudoxus and Callippus, and so he missed the context of some of Aristotle's astronomical works.[83] However, his works influenced astronomer Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji (d. 1204) who adopted most of his reform principles and did succeed in proposing an early astronomical system based on Aristotelian physics.[89]

Physics

In physics, Averroes did not adopt the inductive method that was being developed by Al-Biruni in the Islamic world and is closer to today's physics.[50] Rather, he was—in the words of historian of science Ruth Glasner—an "exegetical" scientist who produced new theses about nature through discussions of previous texts, especially the writings of Aristotle.[90] because of this approach, he was often depicted as an unimaginative follower of Aristotle, but Glasner argues that Averroes's work introduced highly original theories of physics, especially his elaboration of Aristotle's minima naturalia and on motion as forma fluens, which were taken up in the west and are important to the overall development of physics.[91]

Psychology

Averroes expounds his thoughts on psychology in his three commentaries on Aristotle's

In his last commentary—called the Long Commentary—he proposes another theory, which becomes known as the theory of "the

Medicine

While his works in medicine indicate an in-depth theoretical knowledge in medicine of his time, he likely had limited expertise as a practitioner, and declared in one of his works that he had not "practiced much apart from myself, my relatives or my friends."

Another of his departures from Galen and the medical theories of the time is his description of stroke as produced by the brain and caused by an obstruction of the arteries from the heart to the brain.[101] This explanation is closer to the modern understanding of the disease compared to that of Galen, which attributes it to the obstruction between heart and the periphery.[101] He was also the first to describe the signs and symptoms of Parkinson's disease in his Kulliyat, although he did not give the disease a name.[102]

Legacy

In Jewish tradition

Maimonides (d. 1204) was among early Jewish scholars who received Averroes's works enthusiastically, saying he "received lately everything Averroes had written on the works of Aristotle" and that Averroes "was extremely right".[103] Thirteenth-century Jewish writers, including Samuel ibn Tibbon in his work Opinion of the Philosophers, Judah ben Solomon ha-Kohen in his Search for Wisdom and Shem-Tov ibn Falaquera, relied heavily on Averroes's texts.[103] In 1232, Joseph Ibn Kaspi translated Averroes's commentaries on Aristotle's Organon; this was the first Jewish translation of a complete work. In 1260 Moses ibn Tibbon published the translation of almost all of Averroes's commentaries and some of his medical works.[103] Jewish Averroism peaked in the fourteenth century;[104] Jewish writers of this time who translated or were influenced by Averroes include Kalonymus ben Kalonymus of Arles, France, Todros Todrosi of Arles, Elia del Medigo of Candia and Gersonides of Languedoc.[105]

In Latin tradition

Averroes's main influence on the Christian West was through his extensive commentaries on Aristotle.[106] After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, western Europe fell into a cultural decline that resulted in the loss of nearly all of the intellectual legacy of the Classical Greek scholars, including Aristotle.[107] Averroes's commentaries, which were translated into Latin and entered western Europe in the thirteenth century, provided an expert account of Aristotle's legacy and made them available again.[104][108] The influence of his commentaries led to Averroes being referred to simply as "The Commentator" rather than by name in Latin Christian writings.[25] He has been sometimes described as the "father of free thought and unbelief"[109][110] and "father of rationalism".[3]

Authorities of the Roman Catholic Church reacted against the spread of Averroism. In 1270, the

Averroes received a mixed reception from other Catholic thinkers; Thomas Aquinas, a leading Catholic thinker of the thirteenth century, relied extensively on Averroes's interpretation of Aristotle but disagreed with him on many points.[25][114] For example, he wrote a detailed attack on Averroes's theory that all humans share the same intellect.[115] He also opposed Averroes on the eternity of the universe and divine providence.[116] Ramon Llull opposed Averroism and established a distinction between a religion that could be tolerated—Islam—and a philosophy that should be opposed—Averroism, especially in its Latin version.[117]

The Catholic Church's condemnations of 1270 and 1277, and the detailed critique by Aquinas weakened the spread of Averroism in Latin Christendom,[118] though it maintained a following until the sixteenth century, when European thought began to diverge from Aristotelianism.[104] Leading Averroists in the following centuries included John of Jandun and Marsilius of Padua (fourteenth century), Gaetano da Thiene and Pietro Pomponazzi (fifteenth century), and Agostino Nifo and Marcantonio Zimara (sixteenth century).[119]

In Islamic tradition

Averroes had no major influence on Islamic philosophic thought until modern times.

Cultural references

References to Averroes appear in the popular culture of both the western and Muslim world. The poem

Averroes is referenced briefly in

A 1947 short story by

Mael Malihabadi's 1957 Urdu historical fiction novel Falsafi ibn-e Rushd revolves around his life.[130]

Notes

- Arabic: ابن رشد; full namein Arabic: أبو الوليد محمد بن أحمد بن رشد, romanized: Abū al-Walīd Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Rushd

References

- ^ Campo, Juan Eduardo (2009). "Averroes". Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing. p. 337.

- ^ Stone, Caroline (May–June 2003). "Doctor, Philosopher, Renaissance Man". Saudi Aramco World. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-0195376104.

- ^ Tamer, Georges (1 February 2011). "Averroism". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. 3.

Averroism is a philosophical movement named after the sixth/twelfth-century Andalusian philosopher Ibn Rushd (Averroes, d. 595/1198), which began in the thirteenth century among masters of arts at the University of Paris and continued through the seventeenth century.

- ^ a b c d e Arnaldez 1986, p. 909.

- ^ Rosenthal 2017.

- ^ Iskandar 2008, pp. 1115–1116.

- ^ a b Renan 1882, p. 7.

- ^ ISBN 978-9947-39-111-2.

- ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Hillier, Biography.

- ^ Cruz Hernández, Miguel. "Averroes". Real Academia de la Historia.

- ISSN 2659-6636.

- ^ a b c d Wohlman 2009, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Dutton 1994, p. 190.

- ^ a b c d e Iskandar 2008, p. 1116.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Arnaldez 1986, p. 910.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Fakhry 2001, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Dutton 1994, p. 196.

- ^ a b c d e Fakhry 2001, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e Taylor 2005, p. 181.

- ^ Ahmad 1994.

- ^ Adamson 2016, pp. 180–181.

- ^ a b c d e f Adamson 2016, p. 180.

- ^ McGinnis & Reisman 2007, p. 295.

- ^ Arnaldez 1986, pp. 911–912.

- ^ Arnaldez 1986, pp. 913–914.

- ^ Arnaldez 1986, p. 914.

- ^ a b Arnaldez 1986, p. 915.

- ^ a b c Fakhry 2001, p. 124.

- ^ Arnaldez 2000, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Arnaldez 2000, p. 28.

- ^ a b Fakhry 2001, p. xvi.

- ^ Dutton 1994, p. 188.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, p. 115.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, p. 5.

- ^ Leaman 2002, p. 27.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, p. 6.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Fakhry 2001, p. 7.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, p. 9.

- S2CID 143431047.

- ^ a b c d Hillier, Philosophy and Religion.

- ^ Hillier, paragraph 2.

- ^ Leaman 2002, p. 55.

- ^ a b c Guessoum 2011, p. xx.

- ^ a b Adamson 2016, p. 184.

- ^ a b c Guessoum 2011, p. xxii.

- ^ Adamson 2016, p. 182.

- ^ a b Adamson 2016, p. 183.

- ^ a b c d Adamson 2016, p. 181.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hillier, Existence and Attributes of God.

- ^ a b Fakhry 2001, p. 74.

- ^ a b Fakhry 2001, p. 77.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, p. 79.

- ^ Averroës, Tahafut al-Tahafut (The Incoherence of the Incoherence) trans. Simon Van Den Bergh, Luzac & Company 1969, sections 529–536

- ^ Aquinas, Thomas Summa Theologica Book 1 Question 25 article 3

- ^ Fakhry 2001, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Fakhry 2001, p. 18.

- ^ a b Fakhry 2001, p. 19.

- ^ Hillier, Origin of the World.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b c d e Rosenthal 2017, Contents And Significance Of Works.

- ^ a b Fakhry 2001, p. 111.

- ^ a b c Fakhry 2001, p. 106.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, p. 107.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, p. 110.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, pp. 112–114.

- ^ Dutton 1994, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Dutton 1994, p. 195.

- ^ Dutton 1994, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Dutton 1994, p. 192.

- ^ Ibn Rushd 2017, p. 11.

- ^ Dutton 1994, p. 204.

- ^ Dutton 1994, p. 199.

- ^ Dutton 1994, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Dutton 1994, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Dutton 1994, p. 205.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, p. 116.

- ^ a b c d Forcada 2007, pp. 554–555.

- ^ Ariew 2011, p. 193.

- ^ Ariew 2011, pp. 194–195.

- ^ a b Vernet & Samsó 1996, p. 264.

- ^ Vernet & Samsó 1996, p. 266.

- ^ Agutter & Wheatley 2008, p. 44.

- ^ Vernet & Samsó 1996, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Glasner 2009, p. 4.

- ^ Glasner 2009, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c d Adamson 2016, p. 188.

- ^ Adamson 2016, pp. 189–190.

- ^ a b c Adamson 2016, p. 190.

- ^ a b Adamson 2016, p. 191.

- ^ Hasse 2014, Averroes' Unicity Thesis.

- ^ Chandelier 2018, p. 163.

- ^ a b Arnaldez 2000, pp. 27–28.

- ^ a b Belen & Bolay 2009, p. 378.

- ^ Belen & Bolay 2009, pp. 378–379.

- ^ a b Belen & Bolay 2009, p. 379.

- ^ Belen & Bolay 2009, pp. 379–380.

- ^ a b c Fakhry 2001, p. 132.

- ^ a b c Fakhry 2001, p. 133.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, p. 131.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, p. 129.

- ^ Adamson 2016, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Guillaume, Alfred (1945). The Legacy of Islam. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Bratton, Fred (1967). Maimonides, medieval modernist. Beacon Press.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, pp. 133–134.

- ^ a b c d Fakhry 2001, p. 134.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, pp. 134–135.

- ^ a b Fakhry 2001, p. 138.

- ^ Adamson 2016, p. 192.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, p. 140.

- ^ Bordoy Fernandez, Antoni (2002). Ramón Llull y la crítica al averroísmo cristiano (PDF). Universitat de les Illes Balears.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, p. 135.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, pp. 137–138.

- ^ a b c Leaman 2002, p. 28.

- ^ a b Sonneborn 2006, p. 94.

- ^ a b Sonneborn 2006, p. 95.

- J. Carroll Beckwith

- ^ Ben-Menahem 2017, p. 28.

- ^ Ben-Menahem 2017, p. 29.

- ^ Guessoum 2011, p. xiv.

- ISBN 978-0849326738.

- ^ "Averroes". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology Research Program.

- ^ "8318 Averroes (1306 T-2)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ "Falsafi Ibn-e-Rushd by mael malihabadi". Rekhta. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

Works cited

- ISBN 978-0199577491.

- Agutter, Paul S.; Wheatley, Denys N. (2008). Thinking about Life: The history and philosophy of biology and other sciences. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1402088667.

- Ahmad, Jamil (1994). "Averroes". Renaissance. 4 (9). ISSN 1605-0045. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- Ariew, Roger (2011). Descartes Among the Scholastics. Brill. ISBN 978-9004207240.

- ISBN 978-9004081185.

- Arnaldez, Roger (2000) [1998]. Averroes: A Rationalist in Islam. Translated by David Streight. University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 0268020086.

- Ben-Menahem, Yemima (2017). "Borges on Replication and Concept Formation". In Ayelet Shavit; Aaron M. Ellison (eds.). Stepping in the Same River Twice: Replication in Biological Research. Yale University Press. pp. 23–36. ISBN 978-0300228038.

- Chandelier, Joël (2018). "Averroes on Medicine". In Peter Adamson; Matteo Di Giovanni (eds.). Interpreting Averroes. Cambridge University Press. pp. 158–176. ISBN 978-1316335543.

- Belen, Deniz; Bolay, Hayrunnisa (2009). "Averroës in The school of Athens: a Renaissance man and his contribution to Western thought and neuroscience". PMID 19190465.

- Dutton, Yasin (1994). "The Introduction to Ibn Rushd's "Bidāyat al-Mujtahid"". Islamic Law and Society. 1 (2): 188–205. JSTOR 3399333.

- Fakhry, Majid (2001), Averroes (Ibn Rushd) His Life, Works and Influence, ISBN 978-1851682690

- Forcada, Miquel (2007). "Ibn Rushd: Abū al-Walīd Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Rushd al-Ḥafīd". In Thomas Hockey; et al. (eds.). . pp. 564–565.

- Glasner, Ruth (2009). Averroes' Physics: A Turning Point in Medieval Natural Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199567737.

- ISBN 978-1848855182.

- Hasse, Dag Nikolaus (2014). "Influence of Arabic and Islamic Philosophy on the Latin West". In Edward N. Zalta (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- Hillier, H. Chad. "Ibn Rushd (Averroes) (1126–1198)". ISSN 2161-0002.

- Iskandar, Albert Z. (2008). "Ibn Rushd (Averroës)". In Helaine Selin (ed.). ISBN 978-1402045592.

- Leaman, Olivier (2002), An Introduction to Classical Islamic Philosophy (2nd ed.), ISBN 978-0521797573

- McGinnis, Jon; Reisman, David C. (2007). Classical Arabic Philosophy: An Anthology of Sources. Hackett Publishing. ISBN 978-1603843928.

- Renan, Ernest (1882). Averroès et l'Averroïsme: Essai Historique (in French). Calmann-Lévy. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- Sonneborn, Liz (2006). Averroes (Ibn Rushd): Muslim Scholar, Philosopher, and Physician of the Twelfth Century. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1404205147.

- Taylor, Richard C. (2005). "Averroes: religious dialectic and Aristotelian philosophical thought". In Peter Adamson; Richard C. Taylor (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Arabic Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 180–200. ISBN 978-0521520690.

- OCLC 912501823.

- Wohlman, Avital (2009). Al-Ghazali, Averroes and the Interpretation of the Qur'an: Common Sense and Philosophy in Islam. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135224448.

- Rosenthal, Erwin I.J. (26 December 2017). "Averroës". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc.

External links

Works of Averroes

- DARE, the Digital Averroes Research Environment, an ongoing effort to collect digital images of all Averroes manuscripts and full texts of all three language-traditions.

- Averroes, Islamic Philosophy Online (links to works by and about Averroes in several languages)

- The Philosophy and Theology of Averroes: Tractata translated from the Arabic, trans. Mohammad Jamil-ur-Rehman, 1921

- The Incoherence of the Incoherence translation by Simon van den Bergh. [N.B. : Because these refutations consist mainly of commentary on statements by al-Ghazali which are quoted verbatim, this work contains a translation of most of the Tahafut.] There is also an Italian translation by Massimo Campanini, Averroè, L'incoerenza dell'incoerenza dei filosofi, Turin, Utet, 1997.

- [1] SIEPM virtual library, including scanned copies (PDF) of the Editio Juntina of Averroes's works in Latin (Venice 1550–1562)

- Ibn Rushd (2017). Bidayat al-Mujtahid wa Nihayat al-Muqtasid. Dar Al Kotob Al Ilmiyah. ISBN 978-2745134127.

Information about Averroes

- Fouad Ben Ahmed & Robert Pasnau. "Ibn Rushd [Averroes]". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- H. C. Hillier. "Ibn Rushd (Averroes)". on the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Bibliography, a comprehensive overview of the extant bibliography

- Averroes Database, including a full bibliography of his works

- Podcast on Averroes, at NPR's Throughline