Battle of Arnhem

| Battle of Arnhem | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Operation Market Garden | |||||||

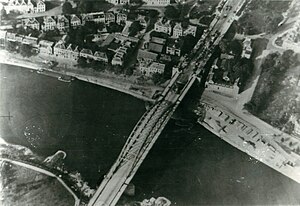

Aerial reconnaissance photo of the Arnhem road bridge taken by the Royal Air Force on 19 September, showing signs of the British defence on the northern ramp and wrecked German vehicles from the previous day's fighting. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

POW ) |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1 reinforced airborne division 1 parachute infantry brigade RAF supply flights Limited support from XXX Corps in later stages |

Initially equivalent to: 1 Kampfgruppe 1 armoured division* | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Approx 1,984 killed 6,854 captured** |

Approx 1,300 killed 2,000 wounded** | ||||||

|

*More details of the German strengths can be found in the German forces section **More detailed information is available in the losses sections | |||||||

The Battle of Arnhem was fought during the

The First Allied Airborne Army was to capture the bridges to secure a route for the Second Army with US, British and Polish airborne troops dropped in the Netherlands along the line of the ground advance, being relieved by the British XXX Corps. Farthest north, the British 1st Airborne Division landed at Arnhem to capture bridges across the Nederrijn (Lower Rhine), with the 1st Polish Parachute Brigade following on. XXX Corps was expected to reach Arnhem in two to three days.

The 1st Airborne Division landed some distance from its objectives and met unexpected resistance, especially from elements of the

The paratroops could not be sufficiently reinforced by the Poles or by XXX Corps when they arrived on the southern bank, nor by Royal Air Force supply flights. After nine days of fighting, the remnants of the division were withdrawn in Operation Berlin. The Allies were unable to advance further and the front line stabilised south of Arnhem. The 1st Airborne Division lost nearly three quarters of its strength and did not see combat again.

Background

By September 1944, Allied forces had broken out of their Normandy beachhead and pursued the remnants of the German armies across northern France and Belgium. Although Allied commanders generally favoured a broad front policy to continue the advance into Germany and the Netherlands, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery proposed a bold plan to head north through Dutch Gelderland, bypassing the German Siegfried Line defences and opening a route into the German industrial heartland of the Ruhr. Initially proposed as a British and Polish operation codenamed Operation Comet, the plan was soon expanded to involve most of the First Allied Airborne Army and a set-piece ground advance into the Netherlands, codenamed Market Garden.[1]

Montgomery's plan involved dropping the US 101st Airborne Division to capture bridges around Eindhoven, the US 82nd Airborne Division to capture crossings around Nijmegen and the British 1st Airborne Division, with the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade, to capture three bridges across the Nederrijn at Arnhem. Lieutenant General Lewis Brereton commanded the First Allied Airborne Army but his second-in-command Lieutenant-General Frederick Browning took command of the airborne operation. The British Second Army, led by XXX Corps, would advance up the "Airborne corridor", securing the airborne divisions' positions and crossing the Rhine within two days. If successful, the plan would open the door to Germany and hopefully force an end to the war in Europe by the end of the year.[2]

British plan

With the British

The division was required to secure the road, rail and

Urquhart decided to land the 1st Parachute Brigade (

The advance into Arnhem would be led by a troop of jeeps from the 1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron (Major Frederick Gough) on Leopard route, who would attempt a coup de main on the road bridge.[14] On the second day, the 4th Parachute Brigade (Brigadier John "Shan" Hackett) would arrive at DZ 'Y', accompanied by extra artillery units and the rest of the Airlanding Brigade on LZ 'X'. Hackett's three battalions would then reinforce the positions north and north west of Arnhem.[12] On the third day, the 1st Independent Polish Parachute Brigade would be dropped south of the river at DZ 'K'.[12] Using the road bridge, they would reinforce the perimeter east of Arnhem, linking with their artillery which would be flown in by glider to LZ 'L'. The 1st Airlanding Brigade would fall back to cover Oosterbeek on the western side of the perimeter and 1st Parachute Brigade would fall back to cover the southern side of the bridges.[12] The remaining units of the division would follow XXX Corps on land in what was known as the sea tail.[12] Once XXX Corps had arrived and advanced beyond the bridgehead, the 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division would land at Deelen airfield to support the ground forces north of the Rhine.[15] The operation would be supplied by daily flights by 38 Group and 46 Group RAF who would make the first drop on LZ 'L' on day 2 and subsequent drops on DZ 'V'.[16][17]

Intelligence

The division was told to expect only limited resistance from German

German forces

The Allied liberation of

The

There were also Dutch units allied to the Germans present at Arnhem. These formations recruited from Dutch nationals (mainly criminals, men wishing to avoid national service or men affiliated with the

As the battle progressed, more and more forces would become available to the Germans.

Battle

Day 1 – Sunday 17 September

The first lift was preceded by intense bombing and strafing by the British

The Airlanding Brigade moved quickly to secure the landing zones. The 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment moved into Wolfheze, the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment secured DZ 'X', deploying its companies around the DZ and in Renkum and the 7th Battalion, King's Own Scottish Borderers moved to secure DZ 'Y'.[40] Here, they ambushed the Dutch SS Wach Battalion as it headed toward Arnhem from Ede.[41] Units of the Airlanding Artillery and Divisional HQ headed into Wolfheze and Oosterbeek where medical officers set up a Regimental Aid Post at the home of Kate ter Horst.[42]

While the 1st Airlanding Brigade moved off from the landing zones, the 1st Parachute Brigade prepared to head east toward the bridges, with Lathbury and his HQ Company following Frost on Lion route. Although some jeeps of the reconnaissance squadron were lost on the flight over, the company formed up in good strength and moved off along Leopard route.[35]

The Germans were unprepared for the landings and thrown into confusion. Model – erroneously assuming that the paratroopers had come to capture him – fled his headquarters at the Tafelberg Hotel in Oosterbeek and went to Bittrich's headquarters east of Arnhem at

The 9th SS division's 40-vehicle reconnaissance battalion under the command of

The Allied advance quickly ran into trouble, the reconnaissance squadron was

Lieutenant Colonel John Frost, commander of the 2nd Parachute Battalion of the 1st Parachute Brigade, had led a mixed group of about 750–800 lightly armed men who had landed near Oosterbeek and marched into Arnhem along the Rhine River route.[55][56] While encountering few Germans and little opposition, the 2nd Battalion had been unable to secure its objectives along the way. The railway bridge at Oosterbeek was blown up by the Germans when the first British paratroops tried to rush across and seize it. The Germans had moved the Old Ship bridge to the south bank. The battalion reached the main road bridge in Arnhem, capturing the northern end but was unable to secure the southern end from the German defenders. The 2nd Parachute Battalion were able to consolidate their position and quickly repulsed the 10th SS Reconnaissance Battalion and other German units when they arrived to secure the bridge.[57]

The Allied advance was severely hampered by poor communications.

Day 2 – Monday 18 September

The 9th SS Panzer Division continued to reinforce the German blocking line. Krafft's unit withdrew overnight and joined Spindler's line, coming under his command.[64] Spindler's force was now becoming so large as more men and units arrived at the new front, that he was forced to split it into battle groups Kampfgruppen Allworden and Harder. The defensive line now blocked the western side of Arnhem and had just closed the gap exploited by Frost along the river the previous evening.[65] Overnight, the 1st and 3rd Parachute Battalions had skirted as far south as 2nd Parachute Battalion's original Lion route, hoping to follow them into Arnhem centre.[66] They approached the German line on the outskirts of the town before light and for several hours attempted to fight through the German positions. Spindler's force – being continually reinforced – was too strong to penetrate and by 10:00 the British advance was stopped.[25] A more coordinated attack followed in the afternoon but it too was repulsed.[67] Urquhart attempted to return to his divisional headquarters at Oosterbeek but became cut off and was forced to take shelter in a Dutch family's loft with two other officers.[68] Lathbury was injured and also forced into hiding.[69]

At the road bridge, German forces of the 9th SS Reconnaissance Battalion had quickly surrounded the 2nd Battalion, cutting them off from the rest of the division.

At the landing zones, Urquhart's Chief of Staff, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Mackenzie, told Hicks that, in Urquhart's and Lathbury's absence, he was acting divisional commander. Mackenzie also advised him to send one of his units – the South Staffords (which was not complete and was awaiting its full complement of men in the second lift) – to Arnhem to help with the advance to the bridge.[73] The South Staffords departed in the morning and joined the 1st Parachute Battalion in the late afternoon.[74]

German forces began to probe the 1st Airlanding Brigade defences in the morning. Units of Kampfgruppe von Tettau attacked the Border's positions; men of the SS NCO school overran Renkum and Kriegsmarine troops engaged the British all day as they withdrew. Minor fighting broke out around LZ 'X' but not enough to seriously hamper the glider landing there.

Despite the setbacks, the units assembled with only slight casualties but the circumstances at Arnhem meant that their roles were quickly changed. The

Day 3 – Tuesday 19 September

With the South Staffords and 11th Parachute Battalion arriving at the positions of the 1st and 3rd Parachute Battalions on the western outskirts of Arnhem, the British hoped to have sufficient troops to break through to Frost's position at the bridge.[85] Lieutenant Colonel Dobie, the commander of the 1st Parachute Battalion, planned to attack before first light, but an erroneous report suggesting that the bridge had fallen led to the attack being cancelled.[86] By the time the report was corrected, first light was due but with reinforcement at the bridge the priority, the attack had to proceed. The advance began on a narrow front between the railway line to the north and the river to the south. The 1st Parachute Battalion led, supported by remnants of the 3rd Parachute Battalion, with the 2nd South Staffordshires on the left flank and the 11th Parachute Battalion following behind.[87] As soon as it became light, the 1st Parachute Battalion was spotted and halted by fire from the main German defensive line. Trapped in open ground and under heavy fire from three sides, the 1st Parachute Battalion disintegrated and what remained of the 3rd Parachute Battalion fell back.[88]

The 2nd South Staffordshires were similarly cut off and save for about 150 men, overcome by midday.

North of the railway line, the 156th and 10th Parachute Battalions tried to seize the high ground in the woods north of Oosterbeek. The advance was slow and by early afternoon they had not advanced any further than their original positions.

In the afternoon, the RAF flew its first big supply mission, with 164 aircraft carrying 390 short tons (350 t) of supplies.

Day 4 – Wednesday 20 September

By now, the 1st Airborne Division was too weak to attempt to reach Frost at the bridge. Eight of the nine infantry battalions were badly mauled or scattered and only the 1st Battalion, The Border Regiment existed as a unit.

The eastern side of this new perimeter was fairly stable after the previous day's retreat from Arnhem, with numerous ad hoc units under company commanders defending the approaches to Oosterbeek. Major Richard Lonsdale had taken command of the outlying units and their positions weathered severe German attacks, before falling back to the main divisional perimeter.[107] This sector was later named Lonsdale Force and would remain the main line of defence on the south-eastern perimeter.[108] The Border Regiment held most of the western edge of the town, with scattered units filling the gaps to the north. As more units fell back to the new defensive area, they were re-organised to establish a thumb-shaped perimeter using the Nederrijn as its southern base.[109] The mixed units at Wolfheze began to fall back in the morning, but several were surrounded and captured, including one party of 130 men.[110] One hundred and fifty men of 156th Parachute Battalion, led by Hackett, became pinned down and took cover in a hollow some 1,300 ft (400 m) west of the Oosterbeek perimeter.[111] The men broke out of the hollow in the late afternoon and approximately 90 of them made it to the Border Regiment's positions.[112]

The afternoon's supply drop went little better than the previous day's. Although a message had reached Britain to arrange a new dropping zone near the Hotel Hartenstein, some aircraft flew to LZ 'Z' where their supplies fell into German hands. At Oosterbeek, the Germans had used British marker panels and flares to attract the aircraft to their positions and the aircraft were unable to distinguish the exact dropping zones. Ten of the 164 aircraft involved were shot down around Arnhem and only 13 per cent of the supplies reached British hands.[113][114]

At the bridge, Frost was finally able to make radio contact with Urquhart and was given the difficult news that reinforcement was doubtful.[115] Shortly afterwards, at about 13:30, Frost was injured in the legs by a mortar bomb, and command passed to Major Gough.[115][116] Despite their stubborn defence of the few buildings they still held, by late afternoon the British position was becoming untenable.[117] When fire took hold of many of the buildings in which the wounded were being treated, a two-hour truce was organised in the late afternoon and the wounded (including Frost) were taken into captivity.[118] Overnight, a few units managed to hold out for a little longer and several groups tried to break out toward the Oosterbeek perimeter, although almost all of them, including Major Hibbert, were captured.[62][119][120] By 05:00 on Thursday morning, all resistance at the bridge had ceased.[121] In later years, Walter Harzer claimed that, during the final hours of fighting, his men intercepted a radio message sent from the bridge that ended with the sentences: "Out of ammunition. God Save the King".[122]

Day 5 – Thursday 21 September

Throughout the morning, the Germans mopped up British survivors and stragglers in hiding around Arnhem bridge. It took several hours to clear the bridge of debris to allow German armour to cross and reinforce Nijmegen. Crucially, the British had held the bridge for long enough for the 82nd Airborne Division and the Guards Armoured Division to capture the Nijmegen bridge.[123] With the resistance at the bridge crushed, the Germans had more troops available for the Oosterbeek engagement, although this changed suddenly in the afternoon.

Delayed by weather, the parachute infantry battalions of Stanisław Sosabowski's 1st (Polish) Parachute Brigade were finally able to take off; 114 C-47s took off but 41 aircraft turned back after Troop Carrier Command decided it would be too dangerous to land if the aircraft were up too long. The remainder pressed on; they did not have the correct transmission codes and did not understand the messages.[124] One of the few messages to get out of Arnhem warned the Poles that DZ 'K' was not secure and to land instead on the polder east of Driel, where they should secure the Heveadorp ferry on the south bank of the Rhine.[125] The Poles dropped under fire at 17:00 and suffered casualties, but assembled in good order. Advancing to the river bank, they discovered that the ferry was gone; the ferryman had sunk it to deny its use to the Germans.[126] The arrival of the Poles relieved the pressure on the British, as the Germans were forced to send more forces south of the Rhine.[127] Fearing an attack on the southern end of the road bridge or the Nijmegen road, a battalion of the 34th SS Volunteer Grenadier Division Landstorm Nederland, Machine Gun Battalion 47 and other Kampfgruppen headed across the river overnight.[128]

At Oosterbeek, the defensive positions were consolidated and organised into two zones. Hicks commanded the western and northern sides of the perimeter and Hackett, after some rest, the east side.[129] The perimeter was not a defensive line but a collection of defensive pockets in houses and foxholes around the centre of Oosterbeek, with the divisional headquarters at the Hotel Hartenstein at its centre. The perimeter was roughly 3 miles (4.8 km) round and was defended by about 3,600 men.[109][130] The Hermann Göring NCO School attacked the Border positions on the west side near the Rhine, forcing them to abandon tactically important high ground overlooking Oosterbeek.[131] The biggest boost to the besieged British was being able to make contact with the 64th Medium Regiment, RA of XXX Corps, which bombarded the German positions around the perimeter.[37] The radio link to the battery headquarters was also used as the main line of communication to XXX Corps.[132] So important was the 64 Medium Regiment that afterwards Urquhart lobbied (unsuccessfully) for the regiment to be able to wear the airborne Pegasus badge on their uniforms.[132]

The British had seen the Polish drop, but were unable to make contact by radio; Private Ernest Henry Archer swam the Rhine with a message. The British planned to supply rafts for a river crossing that night, as the Poles were desperately needed on the northern bank.[133] The Poles waited on the southern bank, but by 03:00 no rafts were evident and they withdrew to Driel to take up defensive positions.[133]

Day 6 – Friday 22 September

Overnight, the Germans south of the river formed a blocking line along the railway, linking up with 10th SS to the south and screening the road bridge from the Poles.

In Oosterbeek, heavy fighting continued around the perimeter. Intense shelling and snipers increased the number of casualties at the aid posts in the hotels and houses of the town.[127] Bittrich ordered that the attacks be stepped up and the British bridgehead north of the Rhine destroyed, and at 09:00 the major attacks began with the various Kampfgruppen of 9th SS attacking from the east and Kampfgruppe von Tettau's units from the west.[135] They made only small gains, but these attacks were followed by simultaneous attacks in the afternoon when the Germans made determined moves on the northern and eastern ends.[136] To the north, they succeeded in briefly forcing back the King's Own Scottish Borderers, before the latter counterattacked and retook their positions.[137] Urquhart realised the futility of holding the tactically unimportant tip however and ordered the units in the north to fall back and defend a shorter line.[138] To the east, the remains of 10th Parachute Battalion were nearly annihilated in their small position on the main Arnhem road, but the Germans failed to gain any significant ground.[139]

Two of Urquhart's staff officers swam the Rhine during the day and made contact with Sosabowski's HQ. It was arranged that six rubber boats should be supplied on the northern bank to enable the Poles to cross the river and come into the Oosterbeek perimeter.[140] That night, the plan was put into operation, but the cable designed to run the boats across broke and the small oars were not enough to paddle across the fast-flowing river.[141] Only 55 Poles made it across before light and only 35 of these made it into the perimeter.[140]

Day 7 – Saturday 23 September

Spindler was ordered to switch his attacks further south to try to force the British away from the river, isolating the British from any hope of reinforcement and allowing them to be destroyed.[135] Despite their best efforts, however, they were unsuccessful, although the constant artillery and assaults continued to wear the British defences down further.[142]

A break in the weather allowed the RAF to finally fly combat missions against the German forces surrounding Urquhart's men.[143] Hawker Typhoons and Republic P-47 Thunderbolts strafed German positions throughout the day and occasionally duelled with the Luftwaffe over the battlefield.[143] The RAF attempted their final resupply flight from Britain on the Saturday afternoon, but lost eight planes for little gain to the airborne troops.[142] Some small resupply efforts would be made from Allied airfields in Europe over the next two days but to little effect.[144]

South of the river, the Poles prepared for another crossing. That night, they awaited the arrival of assault boats from XXX Corps, but these did not arrive until after midnight, and many were without oars. The crossings started at 03:00, with fire support from the 43rd Wessex Division.[145] Through the remaining hours of darkness, only 153 men were able to cross – less than ¼ of the hoped for reinforcement.[146]

Day 8 – Sunday 24 September

In the morning, Horrocks visited the Polish positions at Driel to see the front for himself.[145] Later, he held a conference attended by Browning, Major-General Ivor Thomas of the 43rd (Wessex) Division and Sosabowski at Valburg.[145] In a controversial meeting in which Sosabowski was politically outmanoeuvred, it was decided that another crossing would be attempted that night.[145][147] When the Germans cut the narrow supply road near Nijmegen later that day, it seems that Horrocks realised the futility of the situation and plans were drawn up to withdraw the 1st Airborne Division.[148]

In Oosterbeek, the situation was desperate; Hackett was wounded in the morning and had to give up the eastern command.[149] The RAF attempted some close support around the perimeter which just held but shelling and sniping increased casualties by the hour.[142] The aid stations were occupied by 2,000 men, British, German and Dutch civilian casualties.[150][151] Because many aid posts were in the front line, in homes taken over earlier in the battle, the odd situation was created where casualties were evacuated forward rather than rearwards.[152] Without evacuation, the wounded were often injured again and some posts changed hands between the British and Germans several times as the perimeter was fought over.[150]

During the fighting around Oosterbeek, there had been short, local

That night, the Allies on the south side of the river attempted another crossing. The plan called for 4th Battalion, the Dorset Regiment and the 1st Polish Parachute Battalion to cross at 22:00 using boats and DUKWs.[153] Sosabowski was furious at having to give up control of one of his battalions and thought the plan dangerous but was overruled.[142] The boats took until 1:00 a.m. to arrive, several having been destroyed or lost en route; in a last-minute change of plan, only the Dorsets would cross.[154] The small boats, without skilled crews, the strong current and poor choice of landing site on the north bank meant that of the 315 men who embarked, only a handful reached the British lines on the other side. The DUKWs and most boats landed too far downstream and at least 200 men were captured.[155]

Day 9 – Monday 25 September

During the night, a copy of the withdrawal plan was sent across the river to Urquhart.[156] Despite the obviously frustrating content, Urquhart knew there was little other choice. He radioed Thomas at 08:00 and agreed to the plan, provided it went ahead that night.[157] The Airborne forces would need to endure another day in their perimeter. More men were evacuated from the aid posts throughout the day, but there was no official truce and this was sometimes done under fire.[158] At 10:00, the Germans began their most successful assault on the perimeter, attacking the south-eastern end with infantry supported by newly arrived Tiger tanks.[159] This assault pushed through the defenders' outer lines and threatened to isolate the bulk of the division from the river. Strong counter-attacks from the defenders and concentrated shellfire from south of the river eventually repulsed the Germans.[160]

Urquhart made his withdrawal plan on the model used in the evacuation of

By 21:00, heavy rain had begun to fall, which helped disguise the withdrawal. The bombardment commenced and the units began to fall back to the river. Half of the engineers' boats were too far west to be used (the 43rd (Wessex) Division mistakenly believing the crossing points used by the Dorsets the previous night were in British hands), slowing the evacuation. The Germans shelled the withdrawal, believing it to be a supply attempt.[167] At 05:00, the operation was ended lest the coming light enable the Germans to fire onto the boats more accurately.[168] A total of 2,163 Airborne men, 160 Poles, 75 Dorsets and several dozen other men were evacuated, but about 300 men were left behind on the northern bank when the operation was stopped, and 95 men were killed overnight during the evacuation.[169][170]

During the morning of 26 September, the Germans pressed home their attacks and cut off the bridgehead from the river.[171] It was not until about noon that they realised the British had gone.[171] Later in the day, they rounded up about 600 men, mostly wounded in aid stations and those left behind on the north bank, as well as some pockets of resistance that had been out of radio contact with division headquarters and did not know about the withdrawal.[172] Some of the British and Polish paratroopers managed to avoid capture by the Germans and were sheltered by the Dutch underground. They would be hidden in various houses in the towns and villages, or in huts or makeshift dens in the woods, for around a month until they could be rescued in Operation Pegasus on 22 October 1944.[173]

Aftermath

The Allies withdrew from the southern bank of the Rhine and the front remained on "the island" between the Rhine and Waal rivers. The Germans counter-attacked in October at the Battle of the Nijmegen salient and were repulsed; the front line in the area remained stable until after the winter.[174][175] The bridgeheads across the Maas and Waal served as an important base for operations against the Germans on the Rhine and Operation Veritable into Germany.[176][175]

The Polish Brigade was moved to Nijmegen to defend the withdrawal of British troops in Operation Berlin, before returning to England in early October.[177] Shortly afterwards, the British scapegoated Sosabowski and the Polish Brigade for the failure at Arnhem, perhaps to cover their own failings.[178][179] On 17 October, Montgomery informed Alan Brooke – Chief of the Imperial General Staff – that he felt the Polish forces had "fought very badly" at Arnhem and that he did not want them under his command.[180][181] David Bennett wrote that Montgomery had almost certainly been fed gross misinformation that supported his prejudices.[181]

A month later, Browning wrote a long letter, highly critical of Sosabowski, to Brooke's deputy.[180][182] In it, he accused Sosabowski of being difficult, unadaptable, argumentative and "loth to play his full part in the operation unless everything was done for him and his brigade".[178][182] It is possible that Browning wanted unfairly to blame Sosabowski, although it may equally have been the work of officers of the 43rd Division.[183] Browning recommended that Sosabowski be replaced – suggesting Lieutenant Colonel Jachnik or Major Tonn – and in December the Polish government in exile duly dismissed him, in a move almost certainly made under British pressure.[179][184]

Carlo D'Este wrote "Sosabowski, an experienced and highly competent officer, was removed because he had become an embarrassment to Browning's own ineptitude. Had Sosabowski's counsel been heeded the battle might have been won, even at the eleventh hour."[185] Although it may be fair to say that Sosabowski was difficult to work with, his scapegoating is judged a disgrace in the accounts of many historians.[179][186][178][184][187] Brian Urquhart—who had done so much to warn his superiors about the dangers of Arnhem—described the criticism of Sosabowski and the brigade as "grotesque" and his dismissal as a "shameful act".[188]

Arnhem was a victory for the Germans (albeit tempered by their losses further south) and a defeat for the Second Army.[171][189][190] Many military commentators and historians believe that the failure to secure Arnhem was not the fault of the airborne forces (who had held out for far longer than planned) but of the operation.[191] John Frost noted that "by far the worst mistake was the lack of priority given to the capture of Nijmegen Bridge" and was unable to understand why Browning had ordered Brigadier General James M. Gavin, the commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, to secure the Groesbeek Heights before Nijmegen Bridge.[192][193] In his analysis of the battle, Martin Middlebrook believed the "failure of Browning to give the 82nd US Airborne Division a greater priority in capturing the bridge at Nijmegen" was only just behind the weakness of the air plan in importance.[194]

In his assessment of the German perspective at Arnhem, Robert Kershaw concluded that "the battle on the Waal at Nijmegen proved to be the decisive event" and that Arnhem became a simple matter of containment after the British had retreated into the Oosterbeek perimeter.[195] After that, it was merely "a side-show to the crisis being enacted on the Waal".[195] Heinz Harmel asserted that "The Allies were stopped in the south just north of Nijmegen – that is why Arnhem turned out as it did".[195] Gavin commented that "there was no failure at Arnhem. If, historically, there remains an implication of failure it was the failure of the ground forces to arrive in time to exploit the initial gains of the [1st] Airborne Division".[196]

The air plan was a grave weakness in the events at Arnhem. Middlebrook believes that the refusal to consider night drops, two lifts on day 1 or a coup-de-main assault on Arnhem bridge were "cardinal fundamental errors" and that the failure to land nearer the bridge threw away the airborne force's most valuable asset – that of surprise.[197] Frost believed that the distance from the drop zones to the bridge and the long approach on foot was a "glaring snag" and was highly critical of the "unwillingness of the air forces to fly more than one sortie in the day [which] was one of the chief factors that mitigated against success".[2][198]

The Allies' failure to secure a bridge over the Lower Rhine spelled the end of Market Garden. While all other objectives had been achieved, the failure to secure the Arnhem road bridge over the Rhine meant that the operation failed in its ultimate objective.[175] Montgomery claimed that the operation was 90 per cent successful and the Allies had driven a deep salient into German-occupied territory that was quickly reinforced.[199][175] Milton Shulman observed that the operation had driven a wedge into the German positions, isolating the 15th Army north of Antwerp from the First Parachute Army on the eastern side of the bulge. This complicated the supply problem of the 15th Army and removed the chance of the Germans being able to assemble enough troops for a serious counter-attack to retake Antwerp.[176] Chester Wilmot agreed with this, claiming that the salient was of immense tactical value for the purpose of driving the Germans from the area south of the Maas and removing the threat of an immediate counterattack against Antwerp.[200] Kershaw wrote that the north flank of the west wall was not turned and the 15th Army was able to escape. John Warren wrote that the Allies controlled a salient leading nowhere.[201] John Waddy wrote that the strategic and tactical debate of Market Garden will never be resolved.[202]

Arnhem was described as "a tactical change of plan, designed to meet a favourable local situation within the main plan of campaign," but the result "dispelled the hope that the enemy would be beaten before the winter.

Allied casualties

The battle was a costly defeat and the 1st Airborne Division never recovered. Three-quarters of the division were missing when it returned to England, including two of the three brigade commanders, eight of the nine battalion commanders and 26 of the 30 infantry company commanders.[204] About 500 men were in hiding north of the Rhine and many of these were able to escape during the winter, initially in Operation Pegasus.[170] New recruits, escapees and repatriated POWs joined the division over the coming months but the division was still so understrength that the 4th Parachute Brigade had to merge with the 1st Parachute Brigade; the division could barely produce two brigades of infantry.[204] Between May and August 1945, many of the men were sent to Denmark and Norway to oversee Operation Doomsday, the German surrenders; on their return the division was disbanded.[205][180] The Glider Pilot Regiment suffered the highest proportion of fatalities during the battle (17.3 per cent) and was so depleted that in Operation Varsity, RAF pilots flew many of the gliders.[206][207] As glider operations were abolished after the war, the regiment shrank and was eventually disbanded in 1957.[180]

| Unit | Killed in action/ died of wounds |

Captured/ missing |

Withdrawn | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Airborne | 1,174 | 5,903 | 1,892 | 8,969 |

| Glider Pilot Regiment | 219 | 511 | 532 | 1,262 |

Polish Brigade

|

92 | 111 | 1,486 | 1,689 |

| Total | 1,485 | 6,525 | 3,910 | — |

| Unit | Killed in action/ died of wounds |

Captured/ missing |

|---|---|---|

RAF

|

368 | 79 |

| Royal Army Service Corps | 79 | 44 |

| IX Troop Carrier Command | 27 | 6 |

| XXX Corps | 25 | 200 |

| Total | 499 | 329 |

Axis casualties

German casualty figures are less complete than those of the Allies and official figures have never been released.[209] A signal, possibly sent by II SS Panzer Corps on 27 September, listed 3,300 casualties (1,300 killed and 2,000 injured) around Arnhem and Oosterbeek.[210][211] Robert Kershaw's assessment of the incomplete records identified at least 2,500 casualties.[212] In the Roll of Honour: Battle of Arnhem 17–26 September 1944, J.A. Hey of the Society of Friends of the Airborne Museum, Oosterbeek identified 1,725 German dead from the Arnhem area.[213] All of these figures are significantly higher than Model's conservative estimate of 3,300 casualties for the entire Market Garden area of battle (which included Eindhoven and Nijmegen).[212]

Arnhem

Dutch records suggest that at least 453 civilians died during the battle, either as a result of Allied bombing on the first day or during the subsequent fighting.

Honours and memorials

Although the battle was a disaster for the British 1st Airborne Division, their fight north of the Rhine is considered an example of courage and endurance and one of the greatest feats of arms in the Second World War.[216][217][190] Despite being the last great failure of the British Army,[189] Arnhem has become a byword for the fighting spirit of the British people and has set a standard for the Parachute Regiment.[217] Montgomery claimed that "in years to come it will be a great thing for a man to be able to say: 'I fought at Arnhem'", a prediction seemingly borne out by the pride of soldiers who took part, and the occasional desire of those who did not to claim that they were there.[218][219]

Within days of Operation Berlin, the British returned to a heroes' welcome in England.

- John Baskeyfield, 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment

- Major Robert Cain, 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment

- 10th Battalion, Parachute Regiment

- John Grayburn, 2nd Battalion, Parachute Regiment

The British and Commonwealth system of

In Germany, the battle was treated as a great victory and eight men were awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross.[224][225] The German dead were gathered and buried in the SS Heroes Cemetery near Arnhem, but after the war they were reburied in Ysselsteyn.[226]

The shattered Arnhem road bridge was briefly replaced by a succession of

Eusebius Church, which was largely destroyed, also lost its 32-bell carillon dating back to 1652. Petit & Fritsen constructed a new, 49-bell carillon for the reconstructed church between 1958 and 1964. Since then, the carillon became associated with the yearly war memorial services held each May. In 1994, fifty years after the Battle of Arnhem, four bass bells were added to the instrument, with the largest funded by several English organisations. One of the 1994 bells features a quote from the book A Bridge Too Far and the film adaptation.[230]

The Hotel Hartenstein, used by Urquhart as his headquarters, is now the home of the

To the People of Gelderland; 50 years ago British and Polish Airborne soldiers fought here against overwhelming odds to open the way into Germany and bring the war to an early end. Instead we brought death and destruction for which you have never blamed us. This stone marks our admiration for your great courage remembering especially the women who tended our wounded. In the long winter that followed your families risked death by hiding Allied soldiers and Airmen while members of the resistance led many to safety.[231]

In popular culture

The progress of the battle was widely reported in the British press,[232] thanks largely to the efforts of two BBC reporters (Stanley Maxted and Guy Byam) and three journalists (newspaper reporters Alan Wood of the Daily Express and Jack Smyth of Reuters) who accompanied the British forces.[8] The journalists had their reports sent back almost daily – ironically making communication with London at a time when Divisional Signals had not.[233] The division was also accompanied by a three-man team from the Army Film and Photographic Unit who recorded much of the battle[8] – including many of the images on this page.

In 1945, Louis Hagen, a Jewish refugee from Germany and a British army glider pilot present at the battle, wrote Arnhem Lift, believed to be the first book published about the events at Arnhem.

The English author Richard Adams, an officer in the sea tail of 250th (Airborne) Light Company, Royal Army Service Corps, based the struggle of the anthropomorphised rabbits in his 1972 novel Watership Down (adapted into an animated film in 1978) on the adventures of the officers of the 250 Company of the 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem.[237]

See also

- Arnhem Oosterbeek War Cemetery

- Evacuation of Arnhem, the evacuation of civilians from Arnhem by German forces on 24 and 25 September 1944, lasting until April 1945

- Invasion of Sicily.

- Operation Ladbroke, 1st Airlanding Brigade's operation during the Invasion of Sicily.

- Operation Pegasus, the escape of several Arnhem survivors a month after the battle.

- Second Battle of Arnhem, the April 1945 liberation of the city.

- William of Orange (pigeon)

References

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 9

- ^ a b Frost, p. 198

- ^ Middlebrook, pp. 20–58

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 20

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 39

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 42

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 41

- ^ a b c Middlebrook, p. 68

- ^ Waddy, p. 26

- ^ Ryan, p. 113

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 55

- ^ a b c d e f g Waddy, p. 42

- ^ a b c Waddy, p. 47

- ^ Waddy, pp. 46–47

- ^ Middlebrook, pp. 53–54

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 386

- ^ a b Middlebrook, p. 246

- ^ Frost, p. 200

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 71

- ^ a b c Middlebrook, p. 65

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 66

- ^ a b Badsey, p. 22

- ^ Ryan pp. 53–54

- ^ Ryan, p. 98

- ^ a b Kershaw, p. 108

- ^ Kershaw, p. 94

- ^ a b Kershaw, p. 38

- ^ Ryan, pp. 144–145

- ^ Kershaw, p. 41

- ^ a b Waddy, p. 21

- ^ Ryan, p. 133

- ^ Kershaw, p. 36

- ^ Kershaw, p. 110

- ^ "Defending Arnhem – III./Gren. Rgt. 1 'Landstorm Nederland'". Archived from the original on 28 November 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ^ a b Badsey, p. 43

- ^ Waddy, p. 123

- ^ a b Waddy, p. 124

- ^ Waddy, p. 48

- ^ Waddy, p. 53

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 163

- ^ Middlebrook, pp. 163–164

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 219

- ^ Ryan, p. 199

- ^ Kershaw, p. 103

- ^ Kershaw, p. 309

- ^ Kershaw, pp. 72–73

- ^ Middlebrook, pp. 123–126

- ^ Middlebrook, pp. 135–136

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 142

- ^ Middlebrook, pp. 142–162

- ^ Waddy, p. 61

- ^ Ryan, p. 249

- ^ Waddy, p. 67

- ^ Steer, p. 99

- ^ "76 years ago, the Allies launched the largest airborne attack ever — here's how it all went wrong". Business Insider. 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Operation Market Garden: Last Stand at an Arnhem Schoolhouse". HistoryNet. 8 March 2007.

- ^ Kershaw, pp. 97, 310

- ^ Ryan, pp. 213–214

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 128

- ^ "Reasons for the failure". The Pegasus Archive. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

- ^ a b Kinloch 2023, p. 132.

- ^ a b Roll Call: Major Tony Hibbert, MBE MC Archived 19 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine ParaData, Airborne Assault (Registered Charity)

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 129

- ^ Kershaw, p. 107

- ^ Kershaw, pp. 104–108

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 167

- ^ Waddy, p. 81

- ^ Waddy, p. 84

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 174

- ^ Waddy, p. 82

- ^ Kershaw, p. 131

- ^ Evans, p. 6

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 187

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 188

- ^ Waddy, p. 97

- ^ Waddy, p. 94

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 225

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 234

- ^ Ryan, p. 316

- ^ Kershaw, p. 162

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 250

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 251

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 252

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 400

- ^ Waddy, p. 86

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 190

- ^ Waddy, p. 87

- ^ Middlebrook, pp. 195–196

- ^ Middlebrook, pp. 200–205

- ^ Middlebrook, pp. 206–209

- ^ Middlebrook, pp. 209, 216

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 326

- ^ Middlebrook, pp. 194, 210

- ^ Middlebrook, pp. 269–270

- ^ Middlebrook, pp. 254–260

- ^ a b c Evans, p. 8

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 271

- ^ Waddy, pp. 111–113

- ^ Waddy, p. 115

- ^ Kershaw, p. 206

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 387

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 388

- ^ Steer, p. 100

- ^ Waddy, p. 73

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 325

- ^ a b Waddy, p. 121

- ^ Waddy, p. 134

- ^ Waddy. p. 135

- ^ a b Middlebrook, p. 339

- ^ Middlebrook, pp. 282–286

- ^ Waddy, p. 117

- ^ Waddy, pp. 117–118

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 392

- ^ Evans, p. 12

- ^ a b Frost, p. 229

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 311

- ^ Waddy, p. 75

- ^ Waddy, p. 76

- ^ Major James Anthony Hibbert, The Pegasus Archive – The Battle of Arnhem Archive

- ^ Personal account of Major Tony Hibbert's experiences of the Battle of Arnhem Archived 22 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine ParaData, Airborne Assault (Registered Charity)

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 321

- ^ Ryan, p. 430

- ^ Kershaw, p. 224

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 403

- ^ Waddy, p. 169

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 340

- ^ a b c Evans, p. 16

- ^ a b Kershaw, p. 244

- ^ Middelbrook, p. 339

- ^ Evans, p. 15

- ^ Evans, p. 14

- ^ a b Middlebrook, p. 377

- ^ a b Waddy, p. 170

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 409

- ^ a b Waddy, p. 137

- ^ Waddy, p. 147

- ^ Waddy, p. 148

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 349

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 346

- ^ a b Waddy, p. 173

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 410

- ^ a b c d Evans, p. 18

- ^ a b Kershaw, p. 266

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 398

- ^ a b c d Waddy, p. 174

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 411

- ^ Middlebrook, pp. 414–417

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 417

- ^ Ryan, p. 495

- ^ a b c d Waddy, p. 155

- ^ a b Middlebrook, p. 383

- ^ a b Middlebrook, p. 380

- ^ Middlebrook, pp. 419–420

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 419

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 422

- ^ Waddy, p. 160

- ^ Ryan, p. 515

- ^ Waddy, p. 156

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 424

- ^ Waddy, pp. 140–141

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 427

- ^ a b Waddy, p. 161

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 421

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 429

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 428

- ^ Ryan, p. 519

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 431

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 433

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 434

- ^ a b Waddy, p. 166

- ^ a b c Kershaw, p. 301

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 432

- ^ Kinloch 2023, pp. 163–190.

- ^ a b Badsey, p. 86

- ^ a b c d Kershaw, p. 303

- ^ a b Shulman, p. 210

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 436

- ^ a b c Middlebrook, p. 448

- ^ a b c "The Pegasus Archive – Major-General Stanislaw F. Sosabowski". Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d Middlebrook, p. 447

- ^ a b Bennett p. 238

- ^ a b "Lieutenant-General 'Boy' Browning's letter". Sosabowski Family Website. 20 November 1944. Archived from the original on 17 January 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ^ Bennett, p. 237

- ^ a b Buckingham, p. 199

- ^ D'Este 2015, p. 858.

- ^ Bennett, p. 235

- ^ Bennett, p. 239

- ^ a b "The Sosabowski memorial – Extracts from a welcome speech by Sir Brian Urquhart, KCMG, MBE" (PDF). 16 September 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2009. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ^ a b Middlebrook, p. 1

- ^ a b Ryan, p. 541

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 442

- ^ Frost, preface p. 13

- ^ Frost, p. 242

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 444

- ^ a b c Kershaw, p. 314

- ^ Gavin, p. 121

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 443

- ^ Frost, preface p. 12

- ^ Ryan, p. 537

- ^ Wilmot, p. 523

- ^ Ryan, p. 532

- ^ Waddy, p. 9

- ^ Ehrman 1956, p. 528.

- ^ a b Middlebrook, p. 445

- ^ a b c Middlebrook, p. 446

- ^ a b Middlebrook, p. 439

- ^ "The Assault Glider Trust – RAF Glider Pilots". Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

- ^ Middlebrook, pp. 462–464

- ^ Waddy, p. 167

- ^ a b Middlebrook, p. 441

- ^ Ryan, p. 539

- ^ a b Kershaw, p. 339

- ^ Kershaw, p. 311

- ^ a b c d Middlebrook, p. 449

- ^ Evans, p. 21

- ^ Ambrose, p. 138

- ^ a b Waddy, p. 10

- ^ "BBC News: Arnhem veterans remember comrades". 17 September 2004. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 451

- ^ Rodger, p. 251

- ^ Waddy, p. 190

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 469

- ^ Steer, p. 141

- ^ Frost, p. 235

- ^ "Defending Arnhem – Award Winners". Archived from the original on 13 September 2009. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 450

- ^ Frost, preface p. 16

- ^ "Royal Honours – Military williams Order for Poles". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- ^ "Stichting Driel-Polen – The Sosabowski Memorial". Archived from the original on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ^ "Arnhem, Carillon of the Eusebius Tower (the Netherlands)". Network of War Memorial and Peace Carillons. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Monuments in Arnhem". Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ "Hill 107 – Arnhem Newspapers". Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ^ Middlebrook, p. 164

- ^ "Sergeant Louis Edmund Hagen". Pegasus Archive. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ Frost, p. 251

- ^ Goldman

- ^ Farrier, John (18 May 2012). "10 Facts You Might Not Know about Watership Down". Retrieved 28 June 2014.

Bibliography

- ISBN 0-7434-2990-7.

- Badsey, Stephen (1993). Arnhem 1944, Operation Market Garden. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-302-8.

- Bennett, David (2008). A Magnificent Disaster. Casemate. ISBN 978-1-932033-85-4.

- Buckingham, William (2002). Arnhem 1944. Temps Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-1999-4.

- ISBN 978-1-62779-961-4.

- OCLC 530340578.

- Evans, Martin (1998). The Battle for Arnhem. Pitkin. ISBN 0-85372-888-7.

- ISBN 0-85052-927-1.

- ISBN 0-89839-029-X.

- ISBN 0-340-22340-5. [NB: Book has no page numbers]

- Kershaw, Robert (1990). It Never Snows in September. ISBN 0-7110-2167-8.

- Kinloch, Nicholas (2023). From the Soviet Gulag to Arnhem: A Polish Paratrooper's Epic Wartime Journey. Barnsley: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-399-04591-9.

- ISBN 0-670-83546-3.

- Rodger, Alexander (2003). Battle Honours of the British Empire and Commonwealth Land Forces. Marlborough, UK: The Crowood Press. ISBN 1-86126-637-5.

- ISBN 1-84022-213-1.

- ISBN 0-304-36603-X.

- Steer, Frank (2003). Battleground Europe – Market Garden. Arnhem – The Bridge. Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-85052-939-5.

- ISBN 0-85052-571-3.

- ISBN 1-85326-677-9.

External links

- Operation Market Garden Battle of Arnhem books and photos

- Paradata – Arnhem The Official Airborne Assault Museum online archive.

- The Pegasus Archive Comprehensive information about the battle and Allied units.

- Hill 107 Source material relating to the events at Arnhem.

- Defending Arnhem Information about the German defenders of Arnhem.