History of Christianity in Scotland

| History of Scotland |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of Christianity in Scotland includes all aspects of the Christianity in the region that is now Scotland from its introduction up to the present day. Christianity was first introduced to what is now southern Scotland during the

Christianity in Scotland is often said to have been strongly influenced by monasticism, with abbots being more significant than bishops, although both Kentigern and Ninian were bishops.[2] “It is impossible now to generalise about the nature or structure of the early medieval church in Scotland”.[3] In the Norman period, there was a series of reforms resulting in a clearer parochial structure based around local churches and large numbers of new monastic foundations, which followed continental forms of reformed monasticism, began to predominate. The Scottish church also established its independence from England, developing a clear diocesan structure and becoming a "special daughter of the see of Rome", but it continued to lack Scottish leadership in the form of Archbishops. In the late Middle Ages the crown was able to gain greater influence over senior appointments, and two archbishoprics had been established by the end of the fifteenth century. There was a decline in traditional monastic life, but the mendicant orders of friars grew, particularly in the expanding burghs. New saints and cults of devotion also proliferated. Despite problems over the number and quality of clergy after the Black Death in the fourteenth century, and evidence of heresy in the fifteenth century, the Church in Scotland remained stable.

During the sixteenth century, Scotland underwent a

The late eighteenth century saw the beginnings of a fragmentation of the

From this point there were moves towards reunion that would ultimately result in the majority of the Free Church rejoining the Church of Scotland in 1929. The schisms left small denominations, including the

Middle Ages

Early Christianity

Christianity was probably introduced to what is now southern Scotland during the Roman occupation of Britain.

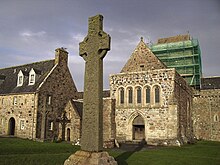

In the sixth century, missionaries from Ireland were operating on the British mainland. This movement is traditionally associated with the figures of

Celtic Church

Early

Gaelic monasticism

Physically Scottish monasteries differed significantly from those on the continent, and were often an isolated collection of wooden huts surrounded by a wall.

Scottish monasticism played a major part in the

Continental monasticism

The introduction of continental forms of monasticism to Scotland is associated with Saxon princess

Ecclesia Scoticana

Before the

Clerics

Up until the early fourteenth century, the Papacy minimised the problem of clerical pluralism, but with relatively poor livings and a shortage of clergy, particularly after the Black Death, in the fifteenth century the number of clerics holding two or more livings rapidly increased.

Saints

Like every other Christian country, one of the main features of Medieval Scotland was the

Popular religion

Traditional Protestant historiography tended to stress the corruption and unpopularity of the late medieval Scottish church, but more recent research has indicated the ways in which it met the spiritual needs of different social groups.

Early modern

Reformation

Early Protestantism

During the sixteenth century, Scotland underwent a

Reformation settlement

Limited toleration and the influence of exiled Scots and Protestants in other countries, led to the expansion of Protestantism, with a group of lairds declaring themselves

James VI

The reign of the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots eventually ended in civil war, deposition, imprisonment and execution in England. Her infant son James VI was crowned King of Scots in 1567.[45] He was brought up as a Protestant, while the country was run by a series of regents.[46] After he asserted his personal rule from 1583 he favoured doctrinal Calvinism, but also episcopacy. His inheritance of the English crown led to rule via the Privy Council from London. He also increasingly controlled the meetings of the Scottish General Assembly and increased the number and powers of the Scottish bishops. In 1618, he held a General Assembly and pushed through Five Articles, which included practices that had been retained in England, but largely abolished in Scotland, most controversially kneeling for the reception of communion. Although ratified, they created widespread opposition and resentment and were seen by many as a step back to Catholic practice.[47]

Seventeenth century

Covenanters

James VI was succeeded by his son

War of Three Kingdoms

The Scots and the king both assembled armies and after two

Commonwealth

After the execution of the king in January 1649 England was declared a

Restoration

After the

Glorious Revolution

Charles died in 1685 and his brother succeeded him as James VII of Scotland (and II of England).

Modern

Eighteenth century

The late eighteenth century saw the beginnings of a fragmentation of the

Long after the triumph of the Church of Scotland in the Lowlands, Highlanders and Islanders clung to an old-fashioned Christianity infused with animistic folk beliefs and practices. The remoteness of the region and the lack of a Gaelic-speaking clergy undermined the missionary efforts of the established church. The later eighteenth century saw some success, owing to the efforts of the SSPCK missionaries and to the disruption of traditional society.[66] Catholicism had been reduced to the fringes of the country, particularly the Gaelic-speaking areas of the Highlands and Islands. Conditions also grew worse for Catholics after the Jacobite rebellions and Catholicism was reduced to little more than a poorly-run mission. Also important was Episcopalianism, which had retained supporters through the civil wars and changes of regime in the seventeenth century. Since most Episcopalians had given their support to the Jacobite rebellions in the early eighteenth century, they also suffered a decline in fortunes.[64]

Nineteenth century

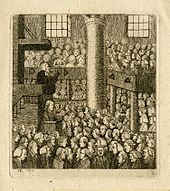

After prolonged years of struggle, in 1834 the Evangelicals gained control of the General Assembly and passed the Veto Act, which allowed congregations to reject unwanted "intrusive" presentations to livings by patrons. The following "Ten Years' Conflict" of legal and political wrangling ended in defeat for the non-intrusionists in the civil courts. The result was a schism from the church by some of the non-intrusionists led by Dr Thomas Chalmers known as the Great Disruption of 1843. Roughly a third of the clergy, mainly from the North and Highlands, formed the separate Free Church of Scotland. The evangelical Free Churches, which were more accepting of Gaelic language and culture, grew rapidly in the Highlands and Islands, appealing much more strongly than did the established church.[66] Chalmers's ideas shaped the breakaway group. He stressed a social vision that revived and preserved Scotland's communal traditions at a time of strain on the social fabric of the country. Chalmers's idealized small equalitarian, kirk-based, self-contained communities that recognized the individuality of their members and the need for cooperation.[67] That vision also affected the mainstream Presbyterian churches, and by the 1870s it had been assimilated by the established Church of Scotland. Chalmers's ideals demonstrated that the church was concerned with the problems of urban society, and they represented a real attempt to overcome the social fragmentation that took place in industrial towns and cities.[68]

In the late nineteenth century, the major debates were between fundamentalist Calvinists and theological liberals, who rejected a literal interpretation of the Bible. This resulted in a further split in the Free Church as the rigid Calvinists broke away to form the

Contemporary Christianity

In the twentieth century, existing Christian denominations were joined by other organisations, including the

The

Notes and references

- ^ Michael Lynch (ed) The Oxford Companion to Scottish History OUP 2007, p78

- ^ ibid p78

- ^ ibid p79

- ISBN 0-903903-24-5, p. 63.

- ISBN 086054138X, p. 93.

- ISBN 0809138948, p. 21.

- ISBN 0520218590, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Thomas Owen Clancy, "The real St Ninian", in The Innes Review, 52 (2001).

- ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, p. 46.

- ISBN 0748601007, pp. 82–3.

- ^ Clancy, "'Nennian recension'", pp. 95–96, Smyth, Warlords and Holy Men, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Markus, "Conversion to Christianity".

- ^ Mentioned by Foster, but more information is available from the Tarbat Discovery Programme: see under External links.

- ^ Bede, IV, cc. 21–22, Clancy, "Church institutions", Clancy, "Nechtan".

- ^ Taylor, "Iona abbots".

- ISBN 0889201668, pp. 77–89.

- ISBN 005003183X, pp. 104–05.

- ^ ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 117–128.

- ISBN 0333567617, p. 58.

- ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, p. 121.

- ^ David N. Dumville, "St Cathróe of Metz and the Hagiography of Exoticism," in John Carey, et al., eds, Irish Hagiography: Saints and Scholars (Dublin, 2001), pp. 172–6.

- ISBN 074860104X, p. 81.

- ^ ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 109–117.

- ^ ISBN 1843840960, pp. 26–9.

- ISBN 0-521-58602-X, pp. 244–5.

- ^ ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 76–87.

- ISBN 074860104X, p. 64.

- ISBN 1446475638, p. 76.

- ISBN 0333567617, pp. 52–3.

- ISBN 0859917657, p. 137.

- ISBN 9004155805.

- ^ ISBN 0748620222, p. 11.

- ISBN 0333567617, p. 55.

- ISBN 1843835622, pp. 178–94.

- ISBN 0-521-44461-6, pp. 349–50.

- ISBN 0-521-58602-X, p. 246.

- ISBN 0-521-58602-X, p. 254.

- ^ ISBN 0-333-63358-X, p. 147.

- ISBN 0-521-58602-X, p. 257.

- ISBN 0748602763, pp. 102–4.

- ISBN 0415163579, p. 414.

- ISBN 0748602763, pp. 120–1.

- ^ ISBN 0748602763, pp. 121–33.

- ^ Peter G. B. McNeill and Hector L. MacQueen, eds., Atlas of Scottish History to 1707 (Edinburgh, 1996), pp. 390–91.

- ISBN 0-333-61395-3, p. 11.

- ISBN 0-7011-6984-2, pp. 51–63.

- ISBN 0415278805, pp. 166–8.

- ISBN 0140136495, p. 201-2.

- ^ Mackie, A History of Scotland pp. 203–4.

- ^ Mackie, A History of Scotland pp. 205–6.

- ISBN 0140136495, pp. 209–10.

- ISBN 0140136495, pp. 211–2.

- ISBN 0140136495, pp. 213–4.

- ISBN 0415278805, pp. 225–6.

- ISBN 0140136495, pp. 221–6.

- ISBN 1446475638, pp. 279–81.

- ^ ISBN 0140136495, pp. 227–8.

- ISBN 0140136495, p. 239.

- ISBN 0140136495, pp. 231–4.

- ISBN 0415278805, p. 253.

- ISBN 0140136495, p. 238.

- ^ ISBN 0140136495, p. 241.

- ISBN 0140136495, pp. 252–3.

- ^ ISBN 1-85109-440-7, pp. 416–7.

- ^ a b c G. M. Ditchfield, The Evangelical Revival (1998), p. 91.

- ^ a b G. Robb, "Popular Religion and the Christianisation of the Scottish Highlands in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries", Journal of Religious History, 1990, 16(1), pp. 18–34.

- ^ J. Brown Stewart, Thomas Chalmers and the godly Commonwealth in Scotland (1982)

- ^ S. Mechie, The Church and Scottish social development, 1780–1870 (1960).

- ^ "Analysis of Religion in the 2001 Census", The Scottish Government, 17 May 2006, archived from the original on 7 June 2011

- ^ "Religious Populations", Office for National Statistics, 11 October 2004, archived from the original on 4 June 2011

- ^ "Religion and belief: some surveys and statistics", British Humanist Association, 24 June 2004, archived from the original on 6 August 2011

- ^ "Queen and the Church". The British Monarchy (Official Website). Archived from the original on 5 June 2011.

- ^ "How we are organised". Church of Scotland. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011.

- ^ "Legacies – Immigration and Emigration – Scotland – Strathclyde – Lithuanians in Lanarkshire". BBC. Retrieved 2011-12-18.

- ^ A. Collier "Scotland's confident Catholics", Tablet 10 January 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Tad Turski (2011-02-01). "Statistics". Dioceseofaberdeen.org. Archived from the original on 2011-11-29. Retrieved 2011-12-18.

- ^ "How many Catholics are there in Britain?". BBC News Website. BBC. 15 September 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ISBN 0416369804, p. 243.

References

- Brown, Callum G. The Social History of Religion in Scotland since 1730 (Methuen, 1987)

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "Church institutions: early medieval" in Lynch (2001).

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "Scotland, the 'Nennian' Recension of the Historia Brittonum and the Libor Bretnach in Simon Taylor (ed.), Kings, clerics and chronicles in Scotland 500–1297. Four Courts, Dublin, 2000. ISBN 1-85182-516-9

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "Nechtan son of Derile" in Lynch (2001).

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "Columba, Adomnán and the Cult of Saints in Scotland" in Broun & Clancy (1999).

- Cross, F.L. and Livingstone, E.A. (eds), Scotland, Christianity in in "The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church", pp. 1471–1473. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1997. ISBN 0-19-211655-X

- Foster, Sally M., Picts, Gaels, and Scots: Early Historic Scotland. Batsford, London, 2004. ISBN 0-7134-8874-3

- Hillis, Peter, The Barony of Glasgow, A Window onto Church and People in Nineteenth Century Scotland, Dunedin Academic Press, 2007.

- Markus, Fr. Gilbert, O.P., "Religious life: early medieval" in Lynch (2001).

- Markus, Fr. Gilbert, O.P., "Conversion to Christianity" in Lynch (2001).

- Mechie, S. The Church and Scottish social development, 1780–1870 (1960).

- Piggott, Charles A. "A geography of religion in Scotland." The Scottish Geographical Magazine 96.3 (1980): 130–140.

- Taylor, Simon, "Seventh-century Iona abbots in Scottish place-names" in Broun & Clancy (1999).

External links

- Census 2001: Key Statistics of Scotland (PDF, religion KS027)

- Church of Scotland

- Roman Catholic Bishops' Conference of Scotland

- Free Church of Scotland

- Scottish Baptist Union

- Scottish Episcopal Church

- Free Church of Scotland (Continuing)

- Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland

- United Free Church of Scotland

- Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Scotland