History of the Church of England

| Part of a series on the |

| History of the Church of England |

|---|

|

The

During the 16th-century

The Settlement failed to end religious disputes. While most of the population gradually conformed to the

In the 1700s and 1800s, revival movements contributed to the rise of Evangelical Anglicanism. In the 19th century, the Oxford Movement gave rise to Anglo-Catholicism, a movement that emphasises the Church of England's Catholic heritage. As the British Empire grew, Anglican churches were established in other parts of the world. These churches consider the Church of England to be a mother church, and it maintains a leading role in the Anglican Communion.

For a general history of Christianity in England, see History of Christianity in Britain.

Middle Ages

Anglo-Saxon period (597–1065)

There is evidence for Christianity in Roman Britain as early as the 3rd century. After 380, Christianity was the official religion of the Roman Empire, and there was some sort of formal church organisation in Britain led by bishops. In the 5th century, the end of Roman rule and invasions by Germanic pagans led to the destruction of any formal church organisation in England. The new inhabitants, the Anglo-Saxons, introduced Anglo-Saxon paganism, and the Christian church was confined to Wales and Cornwall. In Ireland, Celtic Christianity continued to thrive.[2]

The

The Celtic and Roman churches disagreed on several issues. The most important was the

In the late 8th century, Viking raids had a devastating impact on the church in northern and eastern England. Monasteries and churches were raided for wealth in the form of golden crosses, altar plate, and jewels decorating relics and illuminated Bibles. Eventually, the raids turned into wars of conquest and the kingdoms of Northumbria, East Anglia, and parts of Mercia became the Danelaw, whose rulers were Scandinavian pagans.[6] Alfred the Great of Wessex (r. 871–899) and his successors led the Anglo-Saxon resistance and reconquest, culminating in the formation of a single Kingdom of England.

Early organization

Under papal authority, the English church was divided into two ecclesiastical provinces, each led by a metropolitan or archbishop. In the south, the Province of Canterbury was led by the archbishop of Canterbury. It was originally to be based at London, but Augustine and his successors remained at Canterbury instead. In the north, the Province of York was led by the archbishop of York.[7] Theoretically, neither archbishop had precedence over the other. In reality, the south was wealthier than the north, and the result was that Canterbury dominated.[8]

In 668,

A major reorganisation of the English church occurred the late 700s. King Offa of Mercia wanted his own kingdom to have an archbishop since the archbishop of Canterbury was also a great Kentish magnate. In 787, a council of the English church attended by two papal legates elevated the Diocese of Lichfield into an archbishopric. There were now three provinces in England: York, Lichfield and Canterbury.[10] However, this arrangement was abandoned in 803, and Lichfield was reabsorbed into the Province of Canterbury.[11]

Initially, the diocese was the only administrative unit in the Anglo-Saxon church. The bishop served the diocese from a cathedral town with the help of a group of priests known as the bishop's familia. These priests would baptise, teach and visit the remoter parts of the diocese. Familiae were placed in other important settlements, and these were called minsters.[12] Most villages would have had a church by 1042,[13] as the parish system developed as an outgrowth of manorialism. The parish church was a private church built and endowed by the lord of the manor, who retained the right to nominate the parish priest. The priest supported himself by farming his glebe and was also entitled to other support from parishioners. The most important was the tithe, the right to collect one-tenth of all produce from land or animals. Originally, the tithe was a voluntary gift, but the church successfully made it a compulsory tax by the 10th century.[14]

In the late 10th century, the

By 1000, there were eighteen dioceses in England:

Royal authority and ecclesiastical authority were mutually reinforcing. Through the coronation ritual, the church invested the monarch with sacred authority.[17] In return, the church expected royal protection. In addition, the church was a wealthy institution—owning 25–33% of all land according to the Domesday Book. This meant that bishops and abbots had the same status as secular magnates, and it was vital that king's appointed loyal men to these influential offices.[18]

During the Anglo-Saxon period, kings were able to "govern the church largely unimpeded" by appointing bishops and abbots.

Post-Conquest (1066–1500)

In 1066,

The Norman Conquest led to the replacement of the old Anglo-Saxon elite by a new ruling class of

In 1072, William and his archbishop, Lanfranc, sought to complete the programme of reform begun by Archbishop Dunstan. Durham and Rochester cathedrals were refounded as Benedictine monasteries, the secular cathedral of Wells was moved to monastic Bath, while the secular cathedral of Lichfield was moved to Chester, and then to monastic Coventry. Norman bishops were seeking to establish an endowment income entirely separate from that of their cathedral body, and this was inherently more difficult in a monastic cathedral, where the bishop was also titular abbot. Hence, following Lanfranc's death in 1090, a number of bishops took advantage of the vacancy to obtain secular constitutions for their cathedrals – Lincoln, Sarum, Chichester, Exeter and Hereford; while the major urban cathedrals of London and York always remained secular. Furthermore, when the bishops' seats were transferred back from Coventry to Lichfield, and from Bath to Wells, these sees reverted to being secular. Bishops of monastic cathedrals, tended to find themselves embroiled in long-running legal disputes with their respective monastic bodies; and increasingly tended to reside elsewhere. The bishops of Ely and Winchester lived in London as did the archbishop of Canterbury. The bishops of Worcester generally lived in York, while the bishops of Carlisle lived at Melbourne in Derbyshire. Monastic governance of cathedrals continued in England, Scotland and Wales throughout the medieval period; whereas elsewhere in western Europe it was found only at Monreale in Sicily and Downpatrick in Ireland.[23][page needed]

As in other parts of medieval Europe, tension existed between the local monarch and the Pope about civil judicial authority over clerics, taxes and the wealth of the Church, and appointments of bishops, notably during the reigns of

An important aspect in the practice of medieval Christianity was the

John Wycliffe (about 1320 – 31 December 1384) was an English theologian and an early dissident against the Roman Catholic Church during the 14th century. He founded the Lollard movement, which opposed a number of practices of the church. He was also against papal encroachments on secular power. Wycliffe was associated with statements indicating that the Church of Rome is not the head of all churches, nor did St Peter have any more powers given to him than other disciples. These statements were related to his call for a reformation of its wealth, corruption and abuses. Wycliffe, an Oxford scholar, went so far as to state that "The Gospel by itself is a rule sufficient to rule the life of every Christian person on the earth, without any other rule."[citation needed] The Lollard movement continued with his pronouncements from pulpits even under the persecution that followed with Henry IV up to and including the early years of the reign of Henry VIII.

Reformation (1509–1603)

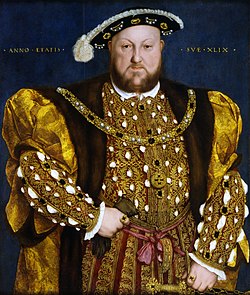

Henry VIII (1509–1547)

In the late Middle Ages, Catholicism was an essential part of English life and culture. The 9,000 parishes covering all of England were overseen by a hierarchy of deaneries, archdeaconries, dioceses led by bishops, and ultimately the pope who presided over the Catholic Church from Rome.[31]

This connection to Rome was severed during the reign of

People supported the separation for different reasons. Important clergy, such as Bishop

But the most important constituency backing royal supremacy were followers of a new movement—

Protestantism had made inroads in England from 1520 onwards, but Protestants had been a persecuted minority considered heretics by both church and state. By 1534, they were Henry's greatest allies. He even chose the Protestant Thomas Cranmer to be archbishop of Canterbury in 1533.[38]

In 1536, the king first exercised his power to pronounce doctrine. That year, the

Edward VI and Mary I (1547–1558)

Henry's son,

The most significant reform in Edward's reign was the adoption of an English liturgy to replace the old Latin rites.

In June 1553, the Church promulgated a Protestant doctrinal statement, the Forty-Two Articles. It affirmed predestination and denied the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. However, three weeks later Edward was dead.[52]

Following the death of Edward, his half-sister the Roman Catholic

Elizabeth I (1558–1603)

When Queen Mary died childless in November 1558, her half-sister became Queen Elizabeth I. The first task was to settle England's religious conflicts. The Elizabethan Religious Settlement established how the Church of England would worship and how it was to be governed. In essence, the Church was returned to where it stood in 1553 before Edward's death. The Act of Supremacy made the monarch the Church's supreme governor. The Act of Uniformity restored a slightly altered 1552 Book of Common Prayer.[54]

Clergy faced fines and imprisonment for refusing to use the liturgy. As Roman Catholics, all the bishops except one refused to swear the

The

The settlement ensured the Church of England was definitively Protestant, but it was unclear what kind of Protestantism was being adopted. It did not help matters that royal injunctions issued in 1559 sometimes contradicted the prayer book. The injunctions specified traditional

The prayer book's

A

Conformists, such as John Bridges and John Whitgift, agreed with Puritans, like Thomas Cartwright, on the doctrines of predestination and election, but they resented Puritans for obsessing over minor ceremonies.[64] There were anti-Calvinists, such as Benjamin Carier and Humphrey Leech. However, criticism of Calvinism was suppressed.[59]

Stuart period (1603 to 1714)

James I (1603–1625)

In 1603, the King of Scotland inherited the English crown as James I. The Church of Scotland was even more strongly Reformed, having a presbyterian polity and John Knox's liturgy, the Book of Common Order. James was himself a moderate Calvinist, and the Puritans hoped the King would move the English Church in the Scottish direction.[65][66] James, however, did the opposite, forcing the Scottish Church to accept bishops and the Five Articles of Perth, all attempts to make it as similar as possible to the English Church.[67]

At the start of his reign, Puritans presented the Millenary Petition to the King. This petition for church reform was referred to the Hampton Court Conference of 1604, which agreed to produce a new version of the Book of Common Prayer that incorporated a few changes requested by the Puritans. The most important outcome of the Conference, however, was the decision to produce a new translation of the Bible, the 1611 King James Version. While a disappointment for Puritans, the provisions were aimed at satisfying moderate Puritans and isolating them from their more radical counterparts.[68]

The Church of England's dominant theology was still Calvinism, but a group of theologians associated with Bishop

English Civil War

For the next century, through the reigns of

Despite this, about one quarter of English clergy refused to conform. In the midst of the apparent triumph of Calvinism, the 17th century brought forth a Golden Age of Anglicanism.[71] The Caroline Divines, such as Andrewes, Laud, Herbert Thorndike, Jeremy Taylor, John Cosin, Thomas Ken and others rejected Roman claims and refused to adopt the ways and beliefs of the Continental Protestants.[71] The historic episcopate was preserved. Truth was to be found in Scripture and the bishops and archbishops, which were to be bound to the traditions of the first four centuries of the Church's history. The role of reason in theology was affirmed.[71]

Restoration

With the

When the new king Charles II reached the throne in 1660, he restored priests who had been expelled from their benefices and actively appointed his supporters who had resisted Cromwell to vacancies. He translated the leading supporters to the most prestigious and rewarding sees. He also considered the need to reestablish episcopal authority and to reincorporate "moderate dissenters" in order to effect Protestant reconciliation. In some cases turnover was heavy—he made four appointments to the diocese of Worcester in four years 1660–63, moving the first three up to better positions.[72]

18th century

Spread of Anglicanism outside England

The history of Anglicanism since the 17th century has been one of greater geographical and cultural expansion and diversity, accompanied by a concomitant diversity of liturgical and theological profession and practice.

At the same time as the English reformation, the

At the time of the English Reformation the four (now six) Welsh dioceses were all part of the Province of Canterbury and remained so until 1920 when the Church in Wales was created as a province of the Anglican Communion. The intense interest in the Christian faith which characterised the Welsh in the 18th and 19th centuries was not present in the sixteenth and most Welsh people went along with the church's reformation more because the English government was strong enough to impose its wishes in Wales rather than out of any real conviction.

Anglicanism spread outside of the British Isles by means of emigration as well as missionary effort. The 1609 wreck of the flagship of the

English missionary organisations such as

19th century

The Church of Ireland, an Anglican establishment, was disestablished in Ireland in 1869.[78] The Church in Wales would later be disestablished in 1919, but in England the Church never lost its established role. However Methodists, Catholics and other denominations were relieved of many of their disabilities through the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts, Catholic emancipation, and parliamentary reform. The Church responded by greatly enlarging its role of activities, and turning to voluntary contributions for funding.[79]

Revivals

The Plymouth Brethren seceded from the established church in the 1820s. The church in this period was affected by the Evangelical revival and the growth of industrial towns in the Industrial Revolution. There was an expansion of the various Nonconformist churches, notably Methodism. From the 1830s the Oxford Movement became influential and occasioned the revival of Anglo-Catholicism. From 1801 the Church of England and the Church of Ireland were unified and this situation lasted until the disestablishment of the Irish church in 1871 (by the Irish Church Act, 1869).

The growth of the twin "

The Catholic Revival had a more penetrating impact by transforming the liturgy of the Anglican Church, repositioning the

Expanded roles at home and worldwide

During the 19th century, the Church expanded greatly at home and abroad. The funding came largely from voluntary contributions. In England and Wales it doubled the number of active clergyman, and built or enlarged several thousand churches. Around mid-century it was consecrating seven new or rebuilt churches every month. It proudly took primary responsibility for a rapid expansion of elementary education, with parish-based schools, and diocesan-based colleges to train the necessary teachers. In the 1870s, the national government assume part of the funding; in 1880 the Church was educating 73% of all students. In addition there was a vigorous home mission, with many clergy, scripture readers, visitors, deaconesses and Anglican sisters in the rapidly growing cities.[80] Overseas the Church kept up with the expanding Empire. It sponsored extensive missionary work, supporting 90 new bishoprics and thousands of missionaries across the globe.[81]

In addition to local endowments and pew rentals,[82] Church financing came from a few government grants,[83] and especially from voluntary contributions. The result was that some old rural parishes were well funded, and most of the rapidly growing urban parishes were underfunded.[84]

| Church of England voluntary contributions, 1860–1885 | per cent |

|---|---|

| Building restoring and endowing churches | 42% |

| Home missions | 9% |

| Foreign missions | 12% |

| Elementary schools and training colleges | 26% |

| Church institution—literary | 1% |

| Church institution—charitable | 5% |

| Clergy charities | 2% |

| Theological schools | 1% |

| Total | 100% |

| £80,500,000 | |

| Source: Clark 1962.[85] |

Prime ministers and the Queen

Throughout the 19th century patronage continued to play a central role in Church affairs. Tory Prime Ministers appointed most of the bishops before 1830, selecting men who had served the party, or had been college tutors of sponsoring politicians, or were near relations of noblemen. In 1815, 11 bishops came from noble families; 10 had been the tutors of a senior official. Theological achievement or personal piety were not critical factors in their selection. Indeed, the Church was often called the "praying section of the Tory party."[86] Not since Newcastle,[87] over a century before, did a prime minister pay as much attention to church vacancies as William Ewart Gladstone. He annoyed Queen Victoria by making appointments she did not like. He worked to match the skills of candidates to the needs of specific church offices. He supported his party by favouring Liberals who would support his political positions.[88] His counterpart, Disraeli, favoured Conservative bishops to a small extent, but took care to distribute bishoprics so as to balance various church factions. He occasionally sacrificed party advantage to choose a more qualified candidate. On most issues Disraeli and Queen Victoria were close, but they frequently clashed over church nominations because of her aversion to high churchmen.[89]

20th century

1914–1970

The current form of military chaplain dates from the era of the First World War. A chaplain provides spiritual and pastoral support for service personnel, including the conduct of religious services at sea or in the field. The Army Chaplains Department was granted the prefix "Royal" in recognition of the chaplains' wartime service. The Chaplain General of the British Army was Bishop John Taylor Smith who held the post from 1901 to 1925.[90]

While the Church of England was historically identified with the upper classes, and with the rural gentry, William Temple, archbishop of Canterbury (1942–1944), was both a prolific theologian and a social activist, preaching Christian socialism and taking an active role in the Labour Party until 1921.[91] He advocated a broad and inclusive membership in the Church of England as a means of continuing and expanding the church's position as the established church. He became archbishop of Canterbury in 1942, and the same year he published Christianity and Social Order. The best-seller attempted to marry faith and socialism—by "socialism" he meant a deep concern for the poor. The book helped solidify Anglican support for the emerging welfare state. Temple was troubled by the high degree of animosity inside, and between the leading religious groups in Britain. He promoted ecumenicism, working to establish better relationships with the Nonconformists, Jews and Catholics, managing in the process to overcome his anti-Catholic bias.[92][93]

Prayer Book Crisis

Parliament passed the Enabling Act in 1919 to enable the new Church Assembly, with three houses for bishops, clergy, and laity, to propose legislation for the Church, subject to formal approval of Parliament.[94][95] A crisis suddenly emerged in 1927 over the Church's proposal to revise the classic Book of Common Prayer, which had been in daily use since 1662. The goal was to better incorporate moderate Anglo-Catholicism into the life of the Church. The bishops sought a more tolerant, comprehensive established Church. After internal debate the Church's new Assembly gave its approval. Evangelicals inside the Church, and Nonconformists outside, were outraged because they understood England's religious national identity to be emphatically Protestant and anti-Catholic. They denounced the revisions as a concession to ritualism and tolerance of Roman Catholicism. They mobilized support in parliament, which twice rejected the revisions after intensely heated debates. The Anglican hierarchy compromised in 1929, while strictly prohibiting extreme and Anglo-Catholic practices.[96][97][98]

World War II and postwar

During the Second World War the head of chaplaincy in the British Army was an Anglican

A movement towards unification with the

Divorce

Standards of morality in Britain changed dramatically after the world wars, in the direction of more personal freedom, especially in sexual matters. The Church tried to hold the line, and was especially concerned to stop the rapid trend toward divorce.[102] It reaffirmed in 1935 that, "in no circumstances can Christian men or women re-marry during the lifetime of a wife or a husband."[103] When king Edward VIII wanted to marry Mrs. Wallis Simpson, a newly divorced woman, in 1936, the archbishop of Canterbury, Cosmo Gordon Lang led the opposition, insisting that Edward must go. Lang was later lampooned in Punch for a lack of "Christian charity".[104]

Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin also objected vigorously to the marriage, noting that "although it is true that standards are lower since the war it only leads people to expect a higher standard from their King." Baldwin refused to consider Churchill's concept of a morganatic marriage where Wallis would not become Queen consort and any children they might have would not inherit the throne. After the governments of the Dominions also refused to support the plan, Edward abdicated in order to marry the woman.[105]

When Princess Margaret wanted in 1952 to marry Peter Townsend, a commoner who had been divorced, the Church did not directly intervene but the government warned she had to renounce her claim to the throne and could not be married in church. Randolph Churchill later expressed concern about rumours about a specific conversation between the archbishop of Canterbury, Geoffrey Fisher, and the Princess while she was still planning to marry Townsend. In Churchill's view, "the rumour that Fisher had intervened to prevent the Princess from marrying Townsend has done incalculable harm to the Church of England", according to research completed by historian Ann Sumner Holmes. Margaret's official statement, however, specified that the decision had been made "entirely alone", although she was mindful of the Church's teaching on the indissolubility of marriage. Holmes summarizes the situation as, "The image that endured was that of a beautiful young princess kept from the man she loved by an inflexible Church. It was an image and a story that evoked much criticism both of Archbishop Fisher and of the Church' policies regarding remarriage after divorce."[106]

However, when Margaret actually did divorce (Antony Armstrong-Jones, 1st Earl of Snowdon), in 1978, the then archbishop of Canterbury, Donald Coggan, did not attack her, and instead offered support.[107]

In 2005,

1970–present

This article needs to be updated. (April 2024) |

The Church Assembly was replaced by the General Synod in 1970.

On 12 March 1994 the Church of England ordained its first female priests. On 11 July 2005 a vote was passed by the Church of England's General Synod in York to allow women's ordination as bishops. Both of these events were subject to opposition from some within the church who found difficulties in accepting them. Adjustments had to be made in the diocesan structure to accommodate those parishes unwilling to accept the ministry of women priests. (See women's ordination)

The first black archbishop of the Church of England, John Sentamu, formerly of Uganda, was enthroned on 30 November 2005 as archbishop of York.

In 2006 the Church of England at its

In 2010, for the first time in the history of the Church of England, more women than men were ordained as priests (290 women and 273 men).[113]

See also

- Church Army

- Church of Ireland#History

- Historical development of Church of England dioceses

- History of the Scottish Episcopal Church

- Religion in the United Kingdom

Notes

- ^ The Chair of St Augustine is the seat of the archbishop of Canterbury and in his role as head of the Anglican Communion. Archbishops of Canterbury are enthroned twice: firstly as diocesan ordinary (and metropolitan and primate of the Church of England) in the archbishop's throne, by the archdeacon of Canterbury; and secondly as leader of the worldwide church in the Chair of St Augustine by the senior (by length of service) archbishop of the Anglican Communion. The stone chair is therefore of symbolic significance throughout Anglicanism.

References

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 29.

- ^ Moorman 1973, pp. 3–4 & 8–9.

- ^ Moorman 1973, pp. 12–14 & 17–18.

- ^ Moorman 1973, p. 19.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 34.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Huscroft 2016, p. 41.

- ^ Moorman 1973, p. 23.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 38.

- ^ Moorman 1973, p. 39.

- ^ Moorman 1973, p. 27.

- ^ a b Huscroft 2016, p. 42.

- ^ Moorman 1973, p. 28.

- ^ Huscroft 2016, p. 44.

- ^ Moorman 1973, p. 48.

- ^ Brown 2003, p. 24.

- ^ a b Huscroft 2016, p. 47.

- ^ Loyn 2000, p. 4.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 10.

- ^ Clifton-Taylor 1967.

- ^ Powell & Wallis 1968, pp. 33–36.

- ^ Swanson 1989.

- ^ John Munns, Cross and Culture in Anglo-Norman England: Theology, Imagery, Devotion (Boydell & Brewer, 2016).

- ^ MacCulloch 1996, p. 210.

- ^ Marshall 2017a, p. 7.

- ^ Marshall 2017a, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Hefling 2021, p. 97–98.

- ^ MacCulloch 2001, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Marshall 2017a, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Marshall 2017a, p. 11.

- ^ Shagan 2017, pp. 29–31.

- ^ Shagan 2017, pp. 33–35.

- ^ Hefling 2021, p. 96.

- ^ Hefling 2021, p. 97.

- ^ Marshall 2017a, p. 126.

- ^ Marshall 2017a, p. 146.

- ^ Shagan 2017, p. 32.

- ^ Shagan 2017, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Shagan 2017, pp. 36–37.

- ^ MacCulloch 1996, p. 372.

- ^ Marshall 2017a, p. 308.

- ^ Duffy 2005, p. 458.

- ^ Duffy 2005, pp. 450–454.

- ^ Haigh 1993, p. 171.

- ^ Shagan 2017, pp. 41.

- ^ Jeanes 2006, p. 30.

- ^ MacCulloch 1996, pp. 412, 414.

- ^ Haigh 1993, p. 179.

- ^ a b c Marshall 2017b, p. 51.

- ^ Marshall 2017a, pp. 340–341.

- ^ Shagan 2017, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Heard 2000, p. 96.

- ^ a b Marshall 2017b, p. 49.

- ^ Haigh 1993, p. 256.

- ^ Haigh 1993, p. 263.

- ^ Haigh 1993, p. 266.

- ^ a b Marshall 2017b, pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b Lake 1995, p. 181.

- ^ Craig 2008, p. 37.

- ^ Craig 2008, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Craig 2008, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Craig 2008, p. 42.

- ^ Lake 1995, p. 183.

- ^ Spinks 2006, p. 48.

- ^ Newton 2005, p. 6.

- ^ Spinks 2006, p. 49.

- ^ Spinks 2006, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Spinks 2006, p. 50.

- ^ Maltby 2006, p. 88.

- ^ a b c Cross & Livingstone 1997, p. 65.

- ^ Beddard 2004.

- ^ Hoppit 2002, pp. 30–39.

- ^ Sheridan Gilley and William J. Sheils, eds. A history of religion in Britain: practice and belief from pre-Roman times to the present. (1994), 168–274.

- ^ J.C.D. Clark, English Society 1688–1832: ideology, social structure and political practice in the ancien regime (1985), pp 119–198

- ^ George Clark, Later Stuarts: 1616–1714 (2nd ed. 1956) pp 153–60.

- ^ See also: Category:American Episcopalians, Category:Scottish Episcopalians

- ^ Christopher F. McCormack, "The Irish Church Disestablishment Act (1869) and the general synod of the Church of Ireland (1871): the art and structure of educational reform." History of Education 47.3 (2018): 303–320.

- ^ Owen Chadwick, The Victorian Church, Part One: 1829–1859 (1966) and The Victorian Church, Part Two: 1860–1901 (1970).

- ^ Sarah Flew, Philanthropy and the Funding of the Church of England: 1856–1914 (2015) excerpt

- ^ Michael Gladwin, Anglican Clergy in Australia, 1788–1850: Building a British World (2015).

- ^ J.C. Bennett, "The Demise and—Eventual—Death of Formal Anglican Pew-Renting in England." Church History and Religious Culture 98.3–4 (2018): 407–424.

- ^ Sarah Flew, "The state as landowner: neglected evidence of state funding of Anglican Church extension in London in the latter nineteenth century." Journal of Church and State 60.2 (2018): 299–317 online.

- ^ G. Kitson Clark, The making of Victorian England (1962) pp. 167–173.

- ^ G. Kitson Clark, The making of Victorian England (1962) page 170.

- ^ D. C Somervell, English thought in the nineteenth century (1929) p. 16

- ^ Donald G. Barnes, "The Duke of Newcastle, Ecclesiastical Minister, 1724–54," Pacific Historical Review 3#2 pp. 164–191

- ^ William Gibson, "'A Great Excitement' Gladstone and Church Patronage 1860–1894." Anglican and Episcopal History 68#3 (1999): 372–396. in JSTOR

- ^ William T. Gibson, "Disraeli's Church Patronage: 1868–1880." Anglican and Episcopal History 61#2 (1992): 197–210. in JSTOR

- ^ Snape 2008, p. vi.

- ^ Adrian Hastings, "Temple, William (1881–1944)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004) https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/36454

- ^ Dianne Kirby, "Christian co-operation and the ecumenical ideal in the 1930s and 1940s." European Review of History 8.1 (2001): 37–60.

- ^ F. A. Iremonger, William Temple, Archbishop of Canterbury: His Life and Letters (1948) pp 387–425. online Archived 18 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 9781442250161.

- ^ Roger Lloyd, The Church of England in the 20th Century (1950)) 2:5-18.

- ^ G. I. T. Machin, "Parliament, the Church of England, and the Prayer Book Crisis, 1927–8." Parliamentary History 19.1 (2000): 131–147.

- ^ John Maiden, National Religion and the Prayer Book Controversy, 1927–1928 (2009).

- ^ John G. Maiden, "English Evangelicals, Protestant National Identity, and Anglican Prayer Book Revision, 1927–1928." Journal of Religious History 34#4 (2010): 430–445.

- ^ Brumwell, P. Middleton (1943) The Army Chaplain: the Royal Army Chaplains' Department; the duties of chaplains and morale. London: Adam & Charles Black

- ISBN 9781473911284.

- ^ Andrew Chandler, "The Church of England and the obliteration bombing of Germany in the Second World War." English Historical Review 108#429 (1993): 920-946.

- ^ G. I. T. Machin, "Marriage and the Churches in the 1930s: Royal abdication and divorce reform, 1936–7." Journal of Ecclesiastical History 42#1 (1991): 68–81.

- ISBN 9781315408491.

- ISBN 9780415669832. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ISBN 9780415669832.

- ISBN 9781848936171.

- ^ Ben Pimlott, The Queen: A Biography of Elizabeth II. (1998), p 443.

- ^ "Divorce and the church: how Charles married Camilla". The Times. 28 November 2017.

- ^ Williams, Rowan (10 February 2005). "Statement of support". Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Charles and Camilla to confess past sins". Fox News. 9 April 2005. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ a b Brown, Jonathan (7 April 2005). "Charles and Camilla to repent their sins". The Independent.

- ^ "Church apologises for slave trade". BBC. 8 February 2006. Retrieved 8 February 2006.

- ^ "More new women priests than men for first time". The Daily Telegraph. 4 February 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

Bibliography

- Beddard, R. A. (2004). "A Reward for Services Rendered: Charles II and the Restoration Bishopric of Worcester, 1660–1663". Midland History. 29 (1). Taylor & Francis: 61–91. S2CID 159847260.

- ISBN 9780802159113.

- Brown, Andrew (2003). Church and Society in England, 1000-1500. Social History in Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0333691458.

- ISBN 978-0-500-20062-9.

- Craig, John (2008), "The Growth of English Puritanism", in Coffey, John; Lim, Paul C. H. (eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Puritanism, Cambridge Companions to Religion, Cambridge University Press, pp. 34–47, ISBN 978-0-521-67800-1

- Cross, F. L.; Livingstone, E. A, eds. (1997). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press, USA.

- Duffy, Eamon (2005). The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, c. 1400 – c. 1580 (2nd ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10828-6.

- ISBN 978-0-19-822162-3.

- Heard, Nigel (2000). Edward VI and Mary: A Mid-Tudor Crisis?. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-74317-1.

- Hefling, Charles (2021). The Book of Common Prayer: A Guide. Guides to Sacred Texts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190689681.

- Hoppit, Julian (2002). A Land of Liberty? England, 1689–1727. New Oxford History of England. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199251002.

- Huscroft, Richard (2016). Ruling England, 1042-1217 (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1138786554.

- Jeanes, Gordon (2006). "Cranmer and Common Prayer". In Hefling, Charles; Shattuck, Cynthia (eds.). ISBN 978-0-19-529756-0.

- Lake, Peter (1995). "Calvinism and the English Church, 1570–1635". In Todd, Margo (ed.). Reformation to Revolution: Politics and Religion in Early Modern England. Rewriting Histories. Routledge. pp. 179–207. ISBN 9780415096928.

- ISBN 9781317884729.

- ISBN 9780300226577.

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2001). The Later Reformation in England, 1547–1603. British History in Perspective (2nd ed.). Palgrave. ISBN 9780333921395.

- ISBN 978-0-19-529756-0.

- Marshall, Peter (2017a). Heretics and Believers: A History of the English Reformation. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300170627.

- Marshall, Peter (2017b). "Settlement Patterns: The Church of England, 1553–1603". In Milton, Anthony (ed.). The Oxford History of Anglicanism. Vol. 1: Reformation and Identity, c. 1520–1662. Oxford University Press. pp. 45–62. ISBN 9780199639731.

- ISBN 978-0819214065.

- Newton, Diana (2005). The Making of the Jacobean Regime: James VI and I and the Government of England, 1603-1605. Studies in History. ISBN 9780861932726.

- ISBN 0297761056.

- Shagan, Ethan H. (2017). "The Emergence of the Church of England, c. 1520–1553". In Milton, Anthony (ed.). The Oxford History of Anglicanism. Vol. 1: Reformation and Identity, c. 1520–1662. Oxford University Press. pp. 28–44. ISBN 9780199639731.

- Spinks, Bryan (2006). "From Elizabeth I to Charles II". In Hefling, Charles; Shattuck, Cynthia (eds.). ISBN 978-0-19-529756-0.

- ISBN 9780007307715.

- Swanson, Robert N. (1989). Church and Society in Late Medieval England. Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0631146598.

Further reading

- Buchanan, Colin. Historical Dictionary of Anglicanism (2nd ed. 2015) excerpt

- Chadwick, Owen. The Victorian Church, Part One: 1829–1859 (1966); The Victorian Church, Part Two: 1860–1901 (1970)

- Coffey, John; Lim, Paul C. H., eds. (2008). The Cambridge Companion to Puritanism. Cambridge Companions to Religion. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-67800-1.

- Flew, Sarah. Philanthropy and the Funding of the Church of England: 1856–1914 (2015) excerpt

- ISBN 978-0-06-063315-8.

- Hardwick, Joseph. An Anglican British world: The Church of England and the expansion of the settler empire, c. 1790–1860 (Manchester UP, 2014).

- Hastings, Adrian. A History of English Christianity 1920–2000 (4th ed. 2001), 704pp, a standard scholarly history.

- Hunt, William (1899). The English Church from Its Foundation to the Norman Conquest (597–1066). Vol. I. Macmillan & Company.

- Kirby, James. Historians and the Church of England: Religion and Historical Scholarship, 1870–1920 (2016) online at DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198768159.001.0001

- Lawson, Tom. God and War: The Church of England and Armed Conflict in the Twentieth Century (Routledge, 2016).

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2003). ISBN 978-0-14-303538-1.

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid (December 2005). "Putting the English Reformation on the Map". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 15. Cambridge University Press: 75–95. S2CID 162188544.

- Maughan Steven S. Mighty England Do Good: Culture, Faith, Empire, and World in the Foreign Missions of the Church of England, 1850–1915 (2014).

- Norman, Edward R. Church and society in England 1770–1970: a historical study (Oxford UP, 1976).

- Picton, Hervé. A Short History of the Church of England: From the Reformation to the Present Day. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015. 180 p.

- Sampson, Anthony. Anatomy of Britain (1962) online free pp 160–73. Sampson had five later updates, but they all left religion out.

- Snape, Michael Francis (2008). The Royal Army Chaplains' Department, 1796–1953: Clergy Under Fire. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-346-8.

- Soloway, Richard Allen. "Church and Society: Recent Trends in Nineteenth Century Religious History." Journal of British Studies 11.2 1972, pp. 142–159. online

- Tapsell, Grant. The later Stuart Church, 1660–1714 (2012).

- Walsh, John; Haydon, Colin; Taylor, Stephen (1993). The Church of England C.1689-c.1833: From Toleration to Tractarianism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-41732-7.