Culture of the Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (960–1279 AD) was a culturally rich and sophisticated age for China. It saw great advancements in the visual arts, music, literature, and philosophy. Officials of the ruling bureaucracy, who underwent a strict and extensive examination process, reached new heights of education in Chinese society, while general Chinese culture was enhanced by widespread printing, growing literacy, and various arts.

Appreciation of art among the

People in urban areas enjoyed

Visual arts

There was a significant difference in painting trends between the Northern Song period (960–1127) and Southern Song period (1127–1279). The paintings of Northern Song officials were influenced by their political ideals of bringing order to the world and tackling the largest issues affecting the whole of their society, hence their paintings often depicted huge, sweeping landscapes.[5] On the other hand, Southern Song officials were more interested in reforming society from the bottom up and on a much smaller scale, a method they believed had a better chance for eventual success.[5] Hence, their paintings often focused on smaller, visually closer, and more intimate scenes, while the background was often depicted as bereft of detail as a realm without substance or concern for the artist or viewer.[5] This change in attitude from one era to the next stemmed largely from the rising influence of Neo-Confucian philosophy. Adherents to Neo-Confucianism focused on reforming society from the bottom up, not the top down, which can be seen in their efforts to promote small private academies during the Southern Song instead of the large state-controlled academies seen in the Northern Song era.[6]

Ever since the

Although they were avid art collectors, some Song scholars did not readily appreciate artworks commissioned by those painters found at shops or common marketplaces, and some of the scholars even criticized artists from renowned schools and academies. Anthony J. Barbieri-Low, a Professor of Early Chinese History at the University of California, Santa Barbara, points out that Song scholars' appreciation of art created by their peers was not extended to those who made a living simply as professional artists:[9]

During the Northern Song (960–1126 CE), a new class of scholar-artists emerged who did not possess the trompe-l'oeil skills of the academy painters nor even the proficiency of common marketplace painters. The literati's painting was simpler and at times quite unschooled, yet they would criticize these other two groups as mere professionals, since they relied on paid commissions for their livelihood and did not paint merely for enjoyment or self-expression. The scholar-artists considered that painters who concentrated on realistic depictions, who employed a colorful palette, or, worst of all, who accepted monetary payment for their work were no better than butchers or tinkers in the marketplace. They were not to be considered real artists.[9]

However, during the Song period, there were many acclaimed court painters and they were highly esteemed by emperors and the

During the Song period Buddhism saw a small revival since its persecution during the Tang dynasty. This could be seen in the continued construction of sculpture artwork at the

Paintings

-

Magpies and Hare, signed and dated by Cui Bai, latter 11th century.

-

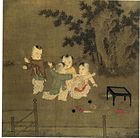

Playing Children, by Su Han Chen, 1150.

-

Cats in the Garden, by Mao Yi, 12th century.

-

Travelers among Mountains and Streams, by Fan Kuan, 11th century

-

Loquatsand Mountain Bird, anonymous painter of the Southern Song

-

Bird on a Branch, Li Anzhong, early-mid 12th century

-

A duckling, anonymous painter of the Southern Song

-

Palace children playing, Northern or Southern Song

-

Early Spring, by Guo Xi (c. 1020–1090), 1072.

-

TheSakyamuni Buddha, by Zhang Shengwen, c. 1173–1176

-

Painting by Emperor Huizong of Song, a renowned scholar and painter, 1112

-

A Scholar in a Meadow, 11th century.

-

The Peacock King, Gunsho Mingwang, 11th century.

-

Birds in a Bamboo and Plum Tree Thicket, 12th century.

-

The White Jasmine Branch, 12th century.

-

Bamboos and Rock, by Li Kan (1244–1320)

-

Cloudy Mountains, by Mi Youren (son of Mi Fu), 1130.

-

Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism are one, a painting in the Litang style, 12th century.

-

Mountain Magpie, Sparrows and Bramble, by Huang Zhucai (933–after 993).

-

Official Song era portrait painting of Empress Cao, wife of Emperor Renzong of Song

-

One of the Nine Dragons by Chen Rong, 1244.

-

Listening to the Wind, by Ma Lin, 1246.

-

Monkey and cats, by Yi Yuanji, 11th century.

-

Holding a Wand Under the Pine Tree, by Xu Daoning, 11th century

-

A Luohan, painted in 1207 by Liu Songnian, Southern Song period

-

Mother Hen and Chicks, anonymous Song artist

-

The Three Friends of Winterby Zhao Mengjian, c. 1199–1264

Ceramics

-

AChinese inkstone with gold and silver markings, from the Nantoyōsō Collection, Japan

-

A Song teapot in the Qingbai style, from Jingdezhen.

-

Longquan ware black stoneware vase with celadon glaze, Song dynasty.

-

A cut and engraved sandstone and celadon jar from Yaozhou in Shaanxi, 10th–11th century.

-

Stoneware with greenish glaze, Northern Song, 10th to 11th century.

-

A small celadon tripod from Yaozhou in Shaanxi, dated to the late 10th century.

-

A small "qinbai" porcelain jar from Jingdezhen in Jiangxi, 11th–12th century.

-

Gray sandstone dish with a celadon coating, decorated with a peony motif, from Yaozhou in Shaanxi, 11th–12th century.

-

A funerary porcelain figurine in the personification of the Chinese zodiac, from Jingdezhen in Jiangxi, 12th century.

-

Celadon plate from Yaozhou in Shaanxi, 10th–11th century.

-

A Song ceramic box with floral medallions

-

A Southern Song (1127–1279) vase with applied dragons and painted floral sprays

-

A Song five-tubed jar with lotus petal design, made of Longquan celadon

-

A pair of stoneware tea bowls from the Song

-

Bluish white glazed figurine,Northern Songperiod

Sculpture

-

Seated Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara (Guanyin), wood and pigment, 11th century

-

The bodhisattva Kuan-yan (Guanyin), Northern Song dynasty, China, c. 1025, wood

-

Bodhisattva, Song Dynasty, 11th–12th century

-

White-glazed pillow in the shape of an infant boy; ding ware, Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127)

-

Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara (Guanyin), limestone, Song dynasty

-

Standing Bodhisattva, China, Song dynasty, 12th century, painted wood

Poetry and literature

Historiography in literature remained prominent during the Song, as it had in previous ages and would in successive ages of China. Along with Song Qi, the essayist and historian Ouyang Xiu were responsible for compiling the

There were also very large encyclopedic works written in the Song period, such as the

There were many technical and scientific writings during the Song period. The two most eminent authors of the scientific and technical fields were

Performing arts

From Kaifeng, the

Color and clothing distinguished the rank of theatre actors in the Song.

Surprisingly, actors on stage did not have a wholesale monopoly on theatrical entertainment, as even vendors and peddlers in the street, singing lewd songs and beating on whatever they could find to compensate for percussion instruments, could draw crowds.[43] This practice was so widespread that West claims "the city itself was turned into a stage and the citizens into the essential audience."[44] Many of the songs played for stage performances were tunes that originated from vendors' and peddlers' songs.[45] Contests were held on New Year's Day to determine which vendor or peddler had the best chants and songs while selling wares; the winners were brought before the imperial court to perform.[44] The Wulin jiushi of the Southern Song states that these vendors, when presented to the consorts and concubines of the palace, were lavished with heaps of gold and pearls for their wares; some vendors would "become rich in a single evening."[37] Theatrical stunts were also performed to gain attention, such as fried-glutinous-rice-ball vendors hanging small red lamps on portable bamboo racks who would twirl them around to the beat of a drum to dazzle crowds.[46] Puppet shows in the streets and wards were also popular.[37]

Festivities

In ancient China, there were many domestic and public pleasures in the rich urban environment unique to the Song dynasty. For the austere and hardworking peasantry, annual festivals and holidays provided a time of joy and relaxation, and for the poorest it meant a chance to borrow food and alcoholic drink so that everyone could join in the celebration.

With the advent of the discovery of gunpowder in China, lavish fireworks displays could also be held during festivities. For example, the martial demonstration in 1110 AD to entertain the court of Emperor Huizong, when it was recorded that a large fireworks display was held alongside Chinese dancers in strange costumes moving through clouds of colored smoke in their performance.[51] The common people also purchased firecrackers from city shopkeepers and vendors, made of simple sticks of bamboo filled with a small amount of gunpowder.[48]

Although they were discontinued after the devastation of the

It was during the Song dynasty that the custom of sitting on chairs instead of floormats became commonplace. However, the older practice continued to be customary for some time, with a Imperial birthday banquet in the Southern Song reportedly involving "officials sitting on sheets with purple edges on the ground". Southern Song scholar Lu You testified that the custom of low-level furniture was preserved in the palace but became phased out among the commoners, and the etiquette rules against the use of chairs was increasingly outdated.[54]

Clothing and apparel

There were many types of clothing and different clothing trends in the Song period, yet clothes in China were always modeled after the seasons and as outward symbols of one's social class.

The attire of Song women was distinguished from men's clothing by being fastened on the left, not on the right.[60] Women wore long dresses or blouses that came down almost to the knee.[60] They also wore skirts and jackets with short or long sleeves.[60] When strolling about outside and along the road, women of wealthy means chose to wear square purple scarves around their shoulders.[60] Ladies also wore hairpins and combs in their hair, while princesses, imperial concubines, and the wives of officials and wealthy merchants wore head ornaments of gold and silver that were shaped in the form of phoenixes and flowers.[57]

People in the Song dynasty never left their homes barefoot, and always had some sort of headgear on.[57] Shops in the city specialized in certain types of hats and headgear, including caps with pointed tails, as well as belts and waistwraps.[61] Only Buddhist monks shaved their heads and strolled about with no headgear or hat of any sort to cover their heads.[57] For footwear, people could purchase leather shoes called 'oiled footwear', wooden sandals, hempen sandals, and the more expensive satin slippers.[57]

Food and cuisine

From the Song period, works such as

Regional differences in culture brought about different types of foods, while in certain areas the cooking traditions of regional cultures blended together; such was the case of the Southern Song capital at

In the early morning in Hangzhou, along the wide avenue of the Imperial Way, special breakfast items and delicacies were sold.

There were also some exotic foreign foods imported to China from abroad, including raisins, dates, Persian

Philosophy

Song intellectuals sought answers to all philosophical and political questions in the Confucian Classics. This renewed interest in the Confucian ideals and society of ancient times coincided with the decline of Buddhism, which was then largely regarded as foreign, and as offering few solutions for practical problems. However, Buddhism in this period continued as a cultural underlay to the more accepted Confucianism and even Taoism, both seen as native and pure by conservative Neo-Confucians. The continuing popularity of Buddhism can be seen with strong evidence by achievements in the arts, such as the 100 painting set of the Five Hundred Luohan, completed by Lin Tinggui and Zhou Jichang in 1178.

The conservative Confucian movement could be seen before the likes of Zhu Xi (1130–1200), with staunch anti-Buddhists such as Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072). In his written work of the Ben-lun, he wrote of his theory for how Buddhism had so easily penetrated Chinese culture during the earlier

"This curse [Buddhism] has overspread the empire for a thousand years, and what can one man in one day do about it? The people are drunk with it, and it has entered the marrow of their bones; it is surely not to be overcome by eloquent talk. What, then, is to be done?[82]

In conclusion on how to root out the 'evil' that was Buddhism, Ouyang Xiu presented a historical example of how it could be uprooted from Chinese culture:

Of old, in the time of the

Warring States, Yang Zhu and Mo Di were engaged in violent controversy. Mencius deplored this and devoted himself to teaching benevolence and righteousness. His exposition of benevolence and righteousness won the day, and the teachings of Mo Di and Yang Zhu were extirpated. In Han times the myriad schools of thought all flourished together. Tung Chung-shu deplored this and revived Confucianism. Therefore the Way of Confucius shone forth, and the myriad schools expired. This is the effect of what I have called "correcting the root cause in order to overcome the evil".[83]

Although Confucianism was cast in stark contrast to the perceived alien and morally inept Buddhism by those such as Ouyang Xiu, Confucianism nonetheless borrowed ideals of Buddhism to provide for its own revival. From Mahayana Buddhism, the Bodhisattva ideal of ethical universalism with benevolent charity and relief to those in need inspired those such as Fan Zhongyan and Wang Anshi, along with the Song government.[84] In contrast to the earlier heavily Buddhist Tang period, where wealthy and pious Buddhist families and Buddhist temples handled much of the charity and alms to the poor, the Song government took on this ideal role instead, through its various programs of welfare and charity (refer to Society section).[85] In addition, the historian Arthur F. Wright notes this situation during the Song period, with philosophical nativism taking from Buddhism its earlier benevolent role:

It is true that Buddhist monks were given official appointments as managers of many of these enterprises, but the initiative came from Neo-Confucian officials. In a sense the Buddhist idea of compassion and many of the measures developed for its practical expression had been appropriated by the Chinese state.[86]

Although Buddhism lost its prominence in the elite circles and government sponsorships of Chinese society, this did not mean the disappearance of Buddhism from Chinese culture.

In terms of Buddhist metaphysics, Zhou Dunyi influenced the beliefs and teachings of Northern Song-era Confucian scholars such as Cheng Hao and Cheng Yi (who were brothers), and was a major influence for Zhu Xi, one of the leading architects of Neo-Confucianism. They emphasized moral self-cultivation over service to the ruler of the state (healing society's ills from the bottom-up, not the top-down), as opposed to statesmen like Fan Zhongyan or Su Shi, who pursued their agenda to advise the ruler to make the best decisions for the common good of all.[88] The Cheng brothers also taught that the workings of nature and metaphysics could be taught through the principle (li) and the vital energy (qi). The principle of nature could be moral or physical, such as the principle of marriage being moral, while the principle of trees is physical. Yet for principles to exist and function normally, there would have to be substance as well as vital energy.[88] This allowed Song intellectuals to validate the teachings of Mencius on the innate goodness of human nature, while at the same time providing an explanation for human wrongdoing.[88] In essence, the principle underlying a human being is good and benevolent, but vital energy has the potential to go astray and be corrupted, giving rise to selfish impulses and all other negative human traits.

The Song

See also

- Culture of China

- Shao Yong

- Society and culture of the Han dynasty

- Song poetry

- The Qing Ding Pearl

Notes

- ^ Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 162.

- ^ Morton, 104.

- ^ Barnhart, "Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting", 93.

- ^ Morton, 105.

- ^ a b c d Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 163.

- ^ Walton, 199.

- ^ Ebrey, 81–83.

- ^ Ebrey, 163.

- ^ a b Barbieri-Low (2007), 39–40.

- ^ Cultural China. "Narcissus". Shanghai News and Press Bureau. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ Sorensen, 282–283.

- ^ a b Pratt & Rutt, 478.

- ^ Brownlee, 19.

- ^ Partington, 238.

- ^ Hargett, 67–68.

- ^ Needham, Volume 1, 136.

- ^ Sivin, III, 32.

- ^ Needham, Volume 3, 208 & 278.

- ^ Wu, 5.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 445–448.

- ^ Bodde, 140.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 107–108.

- ^ Needham, Volume 6, Part 2, 621.

- ^ Needham, Volume 6, Part 2, 623.

- ^ Needham, Volume 3, 521.

- ^ Bol, 44.

- ^ Bol, 46.

- ^ Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 158.

- ^ Hymes, 3.

- ^ a b West, 69.

- ^ West, 69 & 74.

- ^ West, 76.

- ^ West, 98.

- ^ West, 69–70.

- ^ a b c d e West, 70.

- ^ a b c Gernet, 223.

- ^ a b c West, 87.

- ^ Rossabi, 162.

- ^ West, 72.

- ^ West, 78–79.

- ^ Gernet, 224.

- ^ West, 79.

- ^ West, 83–85

- ^ a b West, 85.

- ^ West, 91.

- ^ a b c d e West, 86.

- ^ a b c Gernet, 106.

- ^ a b Gernet, 186.

- ^ a b Needham, Volume 4, Part 1, 128.

- ^ Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 148.

- ^ Kelly, 2.

- ^ Benn, 157.

- ^ Benn, 154–155.

- ISBN 978-1107167865.

- ^ a b Gernet, 131.

- ^ a b Gernet, 127.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gernet, 130.

- ^ a b Gernet, 128.

- ^ Gernet, 127–128.

- ^ a b c d e f Gernet, 129.

- ^ West, 71.

- ^ a b c Gernet, 134.

- ^ a b c d e Gernet, 133.

- ^ West, 73, footnote 17.

- ^ a b Gernet, 137.

- ^ a b c West, 93.

- ^ Gernet, 133–134

- ^ a b Gernet, 183–184

- ^ Gernet, 184.

- ^ a b c West, 73.

- ^ Gernet, 134–135.

- ^ Gernet, 138.

- ^ Gernet, 184–185.

- ^ a b c d Gernet, 135.

- ^ a b Gernet, 136.

- ^ West, 73–74.

- ^ Rossabi, 78.

- ^ West, 75.

- ^ West, 75, footnote 25.

- ^ West, 89.

- ^ Wright, 92.

- ^ Wright, 88.

- ^ Wright, 89.

- ^ Wright, 93.

- ^ Wright, 93–94.

- ^ Wright, 94.

- ^ Brown, 93.

- ^ a b c Ebrey et al., 168.

- ^ a b Ebrey et al., 169.

References

- Banhart, Richard M. et al. (1997). Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09447-7.

- Barbieri-Low, Anthony J. (2007). Artisans in Early Imperial China. Seattle & London: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-98713-8.

- Benn, Charles. 2002. China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517665-0.

- Bodde, Derk (1991). Chinese Thought, Society, and Science. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Bol, Peter K. "The Rise of Local History: History, Geography, and Culture in Southern Song and Yuan Wuzhou," Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies (Volume 61, Number 1, 2001): 37–76.

- Brown, Peter (1971). The World of Late Antiquity. New York: W.W. Norton Inc.

- Brownlee, John S. (1997). Japanese Historians and the National Myths, 1600–1945: The Age of the Gods and Emperor Jinmu. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 0-7748-0645-1.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley, Anne Walthall, ISBN 0-618-13384-4.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley. (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66991-X(paperback).

- Gernet, Jacques (1962). Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276. Translated by H. M. Wright. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0720-0

- Hargett, James M. "Some Preliminary Remarks on the Travel Records of the Song Dynasty (960–1279)," Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews (July 1985): 67–93.

- Hymes, Robert P. (1986). Statesmen and Gentlemen: The Elite of Fu-Chou, Chiang-Hsi, in Northern and Southern Sung. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-30631-0.

- Kelly, Jack (2004). Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, and Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World. New York: Basic Books, Perseus Books Group.

- Morton, Scott and Charlton Lewis (2005). China: Its History and Culture: Fourth Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc.

- Needham, Joseph. (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 1, Introductory Orientations. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph. (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph. (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 1, Physics. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph. (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph. (1986). Science and Civilization: Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology, Part 2, Agriculture. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Partington, James Riddick (1960). A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons Ltd.

- ISBN 0-7007-0463-9.

- Rossabi, Morris (1988). Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05913-1.

- Sivin, Nathan. (1995). Science in Ancient China: Researches and Reflections. Brookfield, Vermont: VARIORUM, Ashgate Publishing.

- Sorensen, Henrik H. 1995. "Buddhist Sculptures from the Song Dynasty at Mingshan Temple in Anyue, Sichuan," Artibus Asiae (Vol. LV, 3/4, 1995): 281–302.

- Walton, Linda (1999). Academies and Society in Southern Sung China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- West, Stephen H. "Playing With Food: Performance, Food, and The Aesthetics of Artificiality in The Sung and Yuan," Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies (Volume 57, Number 1, 1997): 67–106.

- Wright, Arthur F. (1959). Buddhism in Chinese History. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Wu, Jing-nuan (2005). An Illustrated Chinese Materia Medica. New York: Oxford University Press.

Further reading

- Fong, Wen (1973). Sung and Yuan paintings. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-084-5.

External links

- Song Dynasty art and video commentary at Minneapolis Institute of Arts

- Paintings of Song, Liao and Jin dynasties

- Art of the Northern Song Dynasty

- Art of the Southern Song Dynasty