Alkali metal

| Alkali metals | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| ↓ Period | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Lithium (Li) 3 | ||

| 3 | Sodium (Na) 11 | ||

| 4 | Potassium (K) 19 | ||

| 5 | Rubidium (Rb) 37 | ||

| 6 | Caesium (Cs) 55 | ||

| 7 | Francium (Fr) 87 | ||

Legend

| |||

The alkali metals consist of the

The alkali metals are all shiny,

All of the discovered alkali metals occur in nature as their compounds: in order of

Most alkali metals have many different applications. One of the best-known applications of the pure elements is the use of rubidium and caesium in

History

Sodium compounds have been known since ancient times; salt (sodium chloride) has been an important commodity in human activities. While potash has been used since ancient times, it was not understood for most of its history to be a fundamentally different substance from sodium mineral salts. Georg Ernst Stahl obtained experimental evidence which led him to suggest the fundamental difference of sodium and potassium salts in 1702,[6] and Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau was able to prove this difference in 1736.[7] The exact chemical composition of potassium and sodium compounds, and the status as chemical element of potassium and sodium, was not known then, and thus Antoine Lavoisier did not include either alkali in his list of chemical elements in 1789.[8][9]

Pure potassium was first isolated in 1807 in England by

Rubidium and caesium were the first elements to be discovered using the

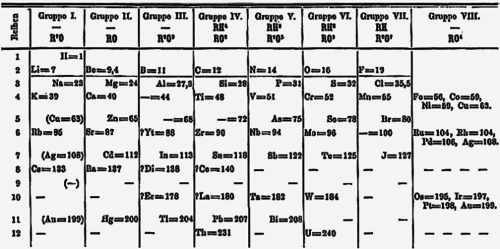

Around 1865

After 1869,

There were at least four erroneous and incomplete discoveries

- 227

89Ac

223

87Fr

223

88Ra

219

86Rn

The next element below francium (eka-francium) in the periodic table would be ununennium (Uue), element 119.[36]: 1729–1730 The synthesis of ununennium was first attempted in 1985 by bombarding a target of einsteinium-254 with calcium-48 ions at the superHILAC accelerator at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in Berkeley, California. No atoms were identified, leading to a limiting yield of 300 nb.[37][38]

It is highly unlikely

Occurrence

In the Solar System

The Oddo–Harkins rule holds that elements with even atomic numbers are more common that those with odd atomic numbers, with the exception of hydrogen. This rule argues that elements with odd atomic numbers have one unpaired proton and are more likely to capture another, thus increasing their atomic number. In elements with even atomic numbers, protons are paired, with each member of the pair offsetting the spin of the other, enhancing stability.[44][45][46] All the alkali metals have odd atomic numbers and they are not as common as the elements with even atomic numbers adjacent to them (the noble gases and the alkaline earth metals) in the Solar System. The heavier alkali metals are also less abundant than the lighter ones as the alkali metals from rubidium onward can only be synthesised in supernovae and not in stellar nucleosynthesis. Lithium is also much less abundant than sodium and potassium as it is poorly synthesised in both Big Bang nucleosynthesis and in stars: the Big Bang could only produce trace quantities of lithium, beryllium and boron due to the absence of a stable nucleus with 5 or 8 nucleons, and stellar nucleosynthesis could only pass this bottleneck by the triple-alpha process, fusing three helium nuclei to form carbon, and skipping over those three elements.[43]

On Earth

The Earth formed from the same cloud of matter that formed the Sun, but the planets acquired different compositions during the formation and evolution of the Solar System. In turn, the natural history of the Earth caused parts of this planet to have differing concentrations of the elements. The mass of the Earth is approximately 5.98×1024 kg. It is composed mostly of iron (32.1%), oxygen (30.1%), silicon (15.1%), magnesium (13.9%), sulfur (2.9%), nickel (1.8%), calcium (1.5%), and aluminium (1.4%); with the remaining 1.2% consisting of trace amounts of other elements. Due to planetary differentiation, the core region is believed to be primarily composed of iron (88.8%), with smaller amounts of nickel (5.8%), sulfur (4.5%), and less than 1% trace elements.[47]

The alkali metals, due to their high reactivity, do not occur naturally in pure form in nature. They are

Sodium and potassium are very abundant on Earth, both being among the ten most common elements in Earth's crust;[49][50] sodium makes up approximately 2.6% of the Earth's crust measured by weight, making it the sixth most abundant element overall[51] and the most abundant alkali metal. Potassium makes up approximately 1.5% of the Earth's crust and is the seventh most abundant element.[51] Sodium is found in many different minerals, of which the most common is ordinary salt (sodium chloride), which occurs in vast quantities dissolved in seawater. Other solid deposits include halite, amphibole, cryolite, nitratine, and zeolite.[51] Many of these solid deposits occur as a result of ancient seas evaporating, which still occurs now in places such as Utah's Great Salt Lake and the Dead Sea.[10]: 69 Despite their near-equal abundance in Earth's crust, sodium is far more common than potassium in the ocean, both because potassium's larger size makes its salts less soluble, and because potassium is bound by silicates in soil and what potassium leaches is absorbed far more readily by plant life than sodium.[10]: 69

Despite its chemical similarity, lithium typically does not occur together with sodium or potassium due to its smaller size.

Rubidium is approximately as abundant as zinc and more abundant than copper. It occurs naturally in the minerals leucite, pollucite, carnallite, zinnwaldite, and lepidolite,[55] although none of these contain only rubidium and no other alkali metals.[10]: 70 Caesium is more abundant than some commonly known elements, such as antimony, cadmium, tin, and tungsten, but is much less abundant than rubidium.[56]

Properties

Physical and chemical

The physical and chemical properties of the alkali metals can be readily explained by their having an ns1 valence

| Name | Lithium | Sodium | Potassium | Rubidium | Caesium | Francium |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic number | 3 | 11 | 19 | 37 | 55 | 87 |

| Standard atomic weight[note 7][57][58] | 6.94(1)[note 8] | 22.98976928(2) | 39.0983(1) | 85.4678(3) | 132.9054519(2) | [223][note 9] |

| Electron configuration | [He] 2s1 | [Ne] 3s1 | [Ar] 4s1 | [Kr] 5s1 | [Xe] 6s1 | [Rn] 7s1 |

| Melting point (°C) | 180.54 | 97.72 | 63.38 | 39.31 | 28.44 | ? |

| Boiling point (°C) | 1342 | 883 | 759 | 688 | 671 | ? |

| Density (g·cm−3) | 0.534 | 0.968 | 0.89 | 1.532 | 1.93 | ? |

Heat of fusion (kJ·mol−1)

|

3.00 | 2.60 | 2.321 | 2.19 | 2.09 | ? |

Heat of vaporisation (kJ·mol−1)

|

136 | 97.42 | 79.1 | 69 | 66.1 | ? |

Heat of formation of monatomic gas (kJ·mol−1)

|

162 | 108 | 89.6 | 82.0 | 78.2 | ? |

Electrical resistivity at 25 °C (nΩ ·cm)

|

94.7 | 48.8 | 73.9 | 131 | 208 | ? |

pm )

|

152 | 186 | 227 | 248 | 265 | ? |

| Ionic radius of hexacoordinate M+ ion (pm) | 76 | 102 | 138 | 152 | 167 | ? |

| First kJ·mol−1 )

|

520.2 | 495.8 | 418.8 | 403.0 | 375.7 | 392.8[67] |

| Electron affinity (kJ·mol−1) | 59.62 | 52.87 | 48.38 | 46.89 | 45.51 | ? |

| Enthalpy of dissociation of M2 (kJ·mol−1) | 106.5 | 73.6 | 57.3 | 45.6 | 44.77 | ? |

| Pauling electronegativity | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.79 | ?[note 10] |

| Allen electronegativity | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.67 |

| Standard electrode potential (E°(M+→M0); V)[70] | −3.04 | −2.71 | −2.93 | −2.98 | −3.03 | ? |

nm )

|

Crimson 670.8 |

Yellow 589.2 |

Violet 766.5 |

Red-violet 780.0 |

Blue 455.5 |

? |

The alkali metals are more similar to each other than the elements in any other

The stable alkali metals are all silver-coloured metals except for caesium, which has a pale golden tint:[72] it is one of only three metals that are clearly coloured (the other two being copper and gold).[10]: 74 Additionally, the heavy alkaline earth metals calcium, strontium, and barium, as well as the divalent lanthanides europium and ytterbium, are pale yellow, though the colour is much less prominent than it is for caesium.[10]: 74 Their lustre tarnishes rapidly in air due to oxidation.[5]

All the alkali metals are highly reactive and are never found in elemental forms in nature.

The second ionisation energy of all of the alkali metals is very high

In aqueous solution, the alkali metal ions form

Lithium

The chemistry of lithium shows several differences from that of the rest of the group as the small Li+ cation

Lithium fluoride is the only alkali metal halide that is poorly soluble in water,

Francium

Francium is also predicted to show some differences due to its high

Nuclear

| Z |

Alkali metal |

Stable |

Decays |

unstable: italics odd–odd isotopes coloured pink

| ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | lithium | 2 | — | 7 Li |

6 Li |

|

| 11 | sodium | 1 | — | 23 Na |

||

| 19 | potassium | 2 | 1 | 39 K |

41 K |

40 K |

| 37 | rubidium | 1 | 1 | 85 Rb |

87 Rb |

|

| 55 | caesium | 1 | — | 133 Cs |

||

| 87 | francium | — | — | No primordial isotopes (223 Fr is a radiogenic nuclide) | ||

| Radioactive: 40K, t1/2 1.25 × 109 years; 87Rb, t1/2 4.9 × 1010 years; 223Fr, t1/2 22.0 min. | ||||||

All the alkali metals have odd atomic numbers; hence, their isotopes must be either

Due to the great rarity of odd–odd nuclei, almost all the primordial isotopes of the alkali metals are odd–even (the exceptions being the light stable isotope lithium-6 and the long-lived

All of the alkali metals except lithium and caesium have at least one naturally occurring

Periodic trends

The alkali metals are more similar to each other than the elements in any other

Atomic and ionic radii

The

The

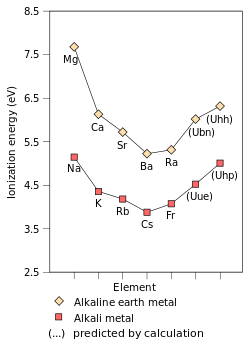

First ionisation energy

The first

The second ionisation energy of the alkali metals is much higher than the first as the second-most loosely held electron is part of a fully filled electron shell and is thus difficult to remove.[5]

Reactivity

The

Electronegativity

Because of the higher electronegativity of lithium, some of its compounds have a more covalent character. For example,

Melting and boiling points

The

Density

The alkali metals all have the same

Compounds

The alkali metals form complete series of compounds with all usually encountered anions, which well illustrate group trends. These compounds can be described as involving the alkali metals losing electrons to acceptor species and forming monopositive ions.

Hydroxides

| External videos | |

|---|---|

The Royal Society of Chemistry |

All the alkali metals react vigorously or explosively with cold water, producing an aqueous solution of a strongly basic alkali metal hydroxide and releasing hydrogen gas.[100] This reaction becomes more vigorous going down the group: lithium reacts steadily with effervescence, but sodium and potassium can ignite, and rubidium and caesium sink in water and generate hydrogen gas so rapidly that shock waves form in the water that may shatter glass containers.[5] When an alkali metal is dropped into water, it produces an explosion, of which there are two separate stages. The metal reacts with the water first, breaking the hydrogen bonds in the water and producing hydrogen gas; this takes place faster for the more reactive heavier alkali metals. Second, the heat generated by the first part of the reaction often ignites the hydrogen gas, causing it to burn explosively into the surrounding air. This secondary hydrogen gas explosion produces the visible flame above the bowl of water, lake or other body of water, not the initial reaction of the metal with water (which tends to happen mostly under water).[74] The alkali metal hydroxides are the most basic known hydroxides.[10]: 87

Recent research has suggested that the explosive behavior of alkali metals in water is driven by a Coulomb explosion rather than solely by rapid generation of hydrogen itself.[105] All alkali metals melt as a part of the reaction with water. Water molecules ionise the bare metallic surface of the liquid metal, leaving a positively charged metal surface and negatively charged water ions. The attraction between the charged metal and water ions will rapidly increase the surface area, causing an exponential increase of ionisation. When the repulsive forces within the liquid metal surface exceeds the forces of the surface tension, it vigorously explodes.[105]

The hydroxides themselves are the most basic hydroxides known, reacting with acids to give salts and with alcohols to give

Intermetallic compounds

The alkali metals form many

Compounds with the group 13 elements

The intermetallic compounds of the alkali metals with the heavier group 13 elements (aluminium, gallium, indium, and thallium), such as NaTl, are poor conductors or semiconductors, unlike the normal alloys with the preceding elements, implying that the alkali metal involved has lost an electron to the Zintl anions involved.[108] Nevertheless, while the elements in group 14 and beyond tend to form discrete anionic clusters, group 13 elements tend to form polymeric ions with the alkali metal cations located between the giant ionic lattice. For example, NaTl consists of a polymeric anion (—Tl−—)n with a covalent diamond cubic structure with Na+ ions located between the anionic lattice. The larger alkali metals cannot fit similarly into an anionic lattice and tend to force the heavier group 13 elements to form anionic clusters.[109]

Compounds with the group 14 elements

Lithium and sodium react with carbon to form acetylides, Li2C2 and Na2C2, which can also be obtained by reaction of the metal with acetylene. Potassium, rubidium, and caesium react with graphite; their atoms are intercalated between the hexagonal graphite layers, forming graphite intercalation compounds of formulae MC60 (dark grey, almost black), MC48 (dark grey, almost black), MC36 (blue), MC24 (steel blue), and MC8 (bronze) (M = K, Rb, or Cs). These compounds are over 200 times more electrically conductive than pure graphite, suggesting that the valence electron of the alkali metal is transferred to the graphite layers (e.g. M+C−8).[65] Upon heating of KC8, the elimination of potassium atoms results in the conversion in sequence to KC24, KC36, KC48 and finally KC60. KC8 is a very strong reducing agent and is pyrophoric and explodes on contact with water.[113][114] While the larger alkali metals (K, Rb, and Cs) initially form MC8, the smaller ones initially form MC6, and indeed they require reaction of the metals with graphite at high temperatures around 500 °C to form.[115] Apart from this, the alkali metals are such strong reducing agents that they can even reduce buckminsterfullerene to produce solid fullerides MnC60; sodium, potassium, rubidium, and caesium can form fullerides where n = 2, 3, 4, or 6, and rubidium and caesium additionally can achieve n = 1.[10]: 285

When the alkali metals react with the heavier elements in the

Nitrides and pnictides

Lithium, the lightest of the alkali metals, is the only alkali metal which reacts with

All the alkali metals react readily with

Oxides and chalcogenides

All the alkali metals react vigorously with

The smaller alkali metals tend to polarise the larger anions (the peroxide and superoxide) due to their small size. This attracts the electrons in the more complex anions towards one of its constituent oxygen atoms, forming an oxide ion and an oxygen atom. This causes lithium to form the oxide exclusively on reaction with oxygen at room temperature. This effect becomes drastically weaker for the larger sodium and potassium, allowing them to form the less stable peroxides. Rubidium and caesium, at the bottom of the group, are so large that even the least stable superoxides can form. Because the superoxide releases the most energy when formed, the superoxide is preferentially formed for the larger alkali metals where the more complex anions are not polarised. The oxides and peroxides for these alkali metals do exist, but do not form upon direct reaction of the metal with oxygen at standard conditions.

Rubidium and caesium can form a great variety of suboxides with the metals in formal oxidation states below +1.[10]: 85 Rubidium can form Rb6O and Rb9O2 (copper-coloured) upon oxidation in air, while caesium forms an immense variety of oxides, such as the ozonide CsO3[125][126] and several brightly coloured suboxides,[127] such as Cs7O (bronze), Cs4O (red-violet), Cs11O3 (violet), Cs3O (dark green),[128] CsO, Cs3O2,[129] as well as Cs7O2.[130][131] The last of these may be heated under vacuum to generate Cs2O.[56]

The alkali metals can also react analogously with the heavier chalcogens (

x and Te2−

x ions.[132] They may be obtained directly from the elements in liquid ammonia or when air is not present, and are colourless, water-soluble compounds that air oxidises quickly back to selenium or tellurium.[10]: 766 The alkali metal polonides are all ionic compounds containing the Po2− ion; they are very chemically stable and can be produced by direct reaction of the elements at around 300–400 °C.[10]: 766 [133][134]

Halides, hydrides, and pseudohalides

The alkali metals are among the most

The alkali metals also react similarly with hydrogen to form ionic alkali metal hydrides, where the hydride anion acts as a pseudohalide: these are often used as reducing agents, producing hydrides, complex metal hydrides, or hydrogen gas.[10]: 83 [65] Other pseudohalides are also known, notably the cyanides. These are isostructural to the respective halides except for lithium cyanide, indicating that the cyanide ions may rotate freely.[10]: 322 Ternary alkali metal halide oxides, such as Na3ClO, K3BrO (yellow), Na4Br2O, Na4I2O, and K4Br2O, are also known.[10]: 83 The polyhalides are rather unstable, although those of rubidium and caesium are greatly stabilised by the feeble polarising power of these extremely large cations.[10]: 835

Coordination complexes

Alkali metal cations do not usually form

Ammonia solutions

The alkali metals dissolve slowly in liquid

Organometallic

Organolithium

Being the smallest alkali metal, lithium forms the widest variety of and most stable

Alkyllithiums and aryllithiums may also react with N,N-disubstituted amides to give aldehydes and ketones, and symmetrical ketones by reacting with carbon monoxide. They thermally decompose to eliminate a β-hydrogen, producing alkenes and lithium hydride: another route is the reaction of ethers with alkyl- and aryllithiums that act as strong bases.[10]: 105 In non-polar solvents, aryllithiums react as the carbanions they effectively are, turning carbon dioxide to aromatic carboxylic acids (ArCO2H) and aryl ketones to tertiary carbinols (Ar'2C(Ar)OH). Finally, they may be used to synthesise other organometallic compounds through metal-halogen exchange.[10]: 106

Heavier alkali metals

Unlike the organolithium compounds, the organometallic compounds of the heavier alkali metals are predominantly ionic. The application of

Alkyl and aryl derivatives of sodium and potassium tend to react with air. They cause the cleavage of

- RM + R'X → R–R' + MX

As such, they have to be made by reacting

The alkali metals and their hydrides react with acidic hydrocarbons, for example

Representative reactions of alkali metals

Reaction with oxygen

Upon reacting with oxygen, alkali metals form oxides, peroxides, superoxides and suboxides. However, the first three are more common. The table below[143] shows the types of compounds formed in reaction with oxygen. The compound in brackets represents the minor product of combustion.

| Alkali metal | Oxide | Peroxide | Superoxide |

| Li | Li2O | (Li2O2) | |

| Na | (Na2O) | Na2O2 | |

| K | KO2 | ||

| Rb | RbO2 | ||

| Cs | CsO2 |

The alkali metal peroxides are ionic compounds that are unstable in water. The peroxide anion is weakly bound to the cation, and it is hydrolysed, forming stronger covalent bonds.

- Na2O2 + 2H2O → 2NaOH + H2O2

The other oxygen compounds are also unstable in water.

- 2KO2 + 2H2O → 2KOH + H2O2 + O2[144]

- Li2O + H2O → 2LiOH

Reaction with sulfur

With sulfur, they form sulfides and polysulfides.[145]

- 2Na + 1/8S8 → Na2S + 1/8S8 → Na2S2...Na2S7

Because alkali metal sulfides are essentially salts of a weak acid and a strong base, they form basic solutions.

- S2- + H2O → HS− + HO−

- HS− + H2O → H2S + HO−

Reaction with nitrogen

Lithium is the only metal that combines directly with nitrogen at room temperature.

- 3Li + 1/2N2 → Li3N

Li3N can react with water to liberate ammonia.

- Li3N + 3H2O → 3LiOH + NH3

Reaction with hydrogen

With hydrogen, alkali metals form saline hydrides that hydrolyse in water.

Reaction with carbon

Lithium is the only metal that reacts directly with carbon to give dilithium acetylide. Na and K can react with acetylene to give acetylides.[146]

Reaction with water

On reaction with water, they generate hydroxide ions and hydrogen gas. This reaction is vigorous and highly exothermic and the hydrogen resulted may ignite in air or even explode in the case of Rb and Cs.[143]

- Na + H2O → NaOH + 1/2H2

Reaction with other salts

The alkali metals are very good reducing agents. They can reduce metal cations that are less electropositive. Titanium is produced industrially by the reduction of titanium tetrachloride with Na at 400 °C (van Arkel–de Boer process).

- TiCl4 + 4Na → 4NaCl + Ti

Reaction with organohalide compounds

Alkali metals react with halogen derivatives to generate hydrocarbon via the Wurtz reaction.

- 2CH3-Cl + 2Na → H3C-CH3 + 2NaCl

Alkali metals in liquid ammonia

Alkali metals dissolve in liquid ammonia or other donor solvents like aliphatic amines or hexamethylphosphoramide to give blue solutions. These solutions are believed to contain free electrons.[143]

- Na + xNH3 → Na+ + e(NH3)x−

Due to the presence of solvated electrons, these solutions are very powerful reducing agents used in organic synthesis.

Reaction 1) is known as Birch reduction. Other reductions[143] that can be carried by these solutions are:

- S8 + 2e− → S82-

- Fe(CO)5 + 2e− → Fe(CO)42- + CO

Extensions

Although francium is the heaviest alkali metal that has been discovered, there has been some theoretical work predicting the physical and chemical characteristics of hypothetical heavier alkali metals. Being the first

The stabilisation of ununennium's valence electron and thus the contraction of the 8s orbital cause its atomic radius to be lowered to 240

Not as much work has been done predicting the properties of the alkali metals beyond ununennium. Although a simple extrapolation of the periodic table (by the

The probable properties of further alkali metals beyond unsepttrium have not been explored yet as of 2019, and they may or may not be able to exist.[147] In periods 8 and above of the periodic table, relativistic and shell-structure effects become so strong that extrapolations from lighter congeners become completely inaccurate. In addition, the relativistic and shell-structure effects (which stabilise the s-orbitals and destabilise and expand the d-, f-, and g-orbitals of higher shells) have opposite effects, causing even larger difference between relativistic and non-relativistic calculations of the properties of elements with such high atomic numbers.[36]: 1732–1733 Interest in the chemical properties of ununennium, unhexpentium, and unsepttrium stems from the fact that they are located close to the expected locations of islands of stability, centered at elements 122 (306Ubb) and 164 (482Uhq).[153][154][155]

Pseudo-alkali metals

Many other substances are similar to the alkali metals in their tendency to form monopositive cations. Analogously to the pseudohalogens, they have sometimes been called "pseudo-alkali metals". These substances include some elements and many more polyatomic ions; the polyatomic ions are especially similar to the alkali metals in their large size and weak polarising power.[156]

Hydrogen

The element

Hydrogen, like the alkali metals, has one valence electron[122] and reacts easily with the halogens,[122] but the similarities mostly end there because of the small size of a bare proton H+ compared to the alkali metal cations.[122] Its placement above lithium is primarily due to its electron configuration.[157] It is sometimes placed above fluorine due to their similar chemical properties, though the resemblance is likewise not absolute.[161]

The first ionisation energy of hydrogen (1312.0

The 1s1 electron configuration of hydrogen, while analogous to that of the alkali metals (ns1), is unique because there is no 1p subshell. Hence it can lose an electron to form the

Ammonium and derivatives

The

Other "pseudo-alkali metals" include the alkylammonium cations, in which some of the hydrogen atoms in the ammonium cation are replaced by alkyl or aryl groups. In particular, the quaternary ammonium cations (NR+4) are very useful since they are permanently charged, and they are often used as an alternative to the expensive Cs+ to stabilise very large and very easily polarisable anions such as HI−2.[10]: 812–9 Tetraalkylammonium hydroxides, like alkali metal hydroxides, are very strong bases that react with atmospheric carbon dioxide to form carbonates.[122]: 256 Furthermore, the nitrogen atom may be replaced by a phosphorus, arsenic, or antimony atom (the heavier nonmetallic pnictogens), creating a phosphonium (PH+4) or arsonium (AsH+4) cation that can itself be substituted similarly; while stibonium (SbH+4) itself is not known, some of its organic derivatives are characterised.[156]

Cobaltocene and derivatives

Thallium

Copper, silver, and gold

The

In Mendeleev's 1871 periodic table, copper, silver, and gold are listed twice, once under group VIII (with the

The coinage metals were traditionally regarded as a subdivision of the alkali metal group, due to them sharing the characteristic s1 electron configuration of the alkali metals (group 1: p6s1; group 11: d10s1). However, the similarities are largely confined to the

Production and isolation

The production of pure alkali metals is somewhat complicated due to their extreme reactivity with commonly used substances, such as water.[5][65] From their silicate ores, all the stable alkali metals may be obtained the same way: sulfuric acid is first used to dissolve the desired alkali metal ion and aluminium(III) ions from the ore (leaching), whereupon basic precipitation removes aluminium ions from the mixture by precipitating it as the hydroxide. The remaining insoluble alkali metal carbonate is then precipitated selectively; the salt is then dissolved in hydrochloric acid to produce the chloride. The result is then left to evaporate and the alkali metal can then be isolated.[65] Lithium and sodium are typically isolated through electrolysis from their liquid chlorides, with calcium chloride typically added to lower the melting point of the mixture. The heavier alkali metals, however, are more typically isolated in a different way, where a reducing agent (typically sodium for potassium and magnesium or calcium for the heaviest alkali metals) is used to reduce the alkali metal chloride. The liquid or gaseous product (the alkali metal) then undergoes fractional distillation for purification.[65] Most routes to the pure alkali metals require the use of electrolysis due to their high reactivity; one of the few which does not is the pyrolysis of the corresponding alkali metal azide, which yields the metal for sodium, potassium, rubidium, and caesium and the nitride for lithium.[122]: 77

Lithium salts have to be extracted from the water of mineral springs, brine pools, and brine deposits. The metal is produced electrolytically from a mixture of fused lithium chloride and potassium chloride.[184]

Sodium occurs mostly in seawater and dried seabed,[5] but is now produced through electrolysis of sodium chloride by lowering the melting point of the substance to below 700 °C through the use of a Downs cell.[185][186] Extremely pure sodium can be produced through the thermal decomposition of sodium azide.[187] Potassium occurs in many minerals, such as sylvite (potassium chloride).[5] Previously, potassium was generally made from the electrolysis of potassium chloride or potassium hydroxide,[188] found extensively in places such as Canada, Russia, Belarus, Germany, Israel, United States, and Jordan, in a method similar to how sodium was produced in the late 1800s and early 1900s.[189] It can also be produced from seawater.[5] However, these methods are problematic because the potassium metal tends to dissolve in its molten chloride and vaporises significantly at the operating temperatures, potentially forming the explosive superoxide. As a result, pure potassium metal is now produced by reducing molten potassium chloride with sodium metal at 850 °C.[10]: 74

- Na (g) + KCl (l) ⇌ NaCl (l) + K (g)

Although sodium is less reactive than potassium, this process works because at such high temperatures potassium is more volatile than sodium and can easily be distilled off, so that the equilibrium shifts towards the right to produce more potassium gas and proceeds almost to completion.[10]: 74

Metals like sodium are obtained by electrolysis of molten salts. Rb & Cs obtained mainly as by products of Li processing. To make pure caesium, ores of caesium and rubidium are crushed and heated to 650 °C with sodium metal, generating an alloy that can then be separated via a fractional distillation technique. Because metallic caesium is too reactive to handle, it is normally offered as caesium azide (CsN3). Caesium hydroxide is formed when caesium interacts aggressively with water and ice (CsOH).[190]

Rubidium is the 16th most abundant element in the earth's crust; however, it is quite rare. Some minerals found in North America, South Africa, Russia, and Canada contain rubidium. Some potassium minerals (lepidolites, biotites, feldspar, carnallite) contain it, together with caesium. Pollucite, carnallite, leucite, and lepidolite are all minerals that contain rubidium. As a by-product of lithium extraction, it is commercially obtained from lepidolite. Rubidium is also found in potassium rocks and brines, which is a commercial supply. The majority of rubidium is now obtained as a byproduct of refining lithium. Rubidium is used in vacuum tubes as a getter, a material that combines with and removes trace gases from vacuum tubes.[191][192]

For several years in the 1950s and 1960s, a by-product of the potassium production called Alkarb was a main source for rubidium. Alkarb contained 21% rubidium while the rest was potassium and a small fraction of caesium.[193] Today the largest producers of caesium, for example the Tanco Mine in Manitoba, Canada, produce rubidium as by-product from pollucite.[194] Today, a common method for separating rubidium from potassium and caesium is the fractional crystallisation of a rubidium and caesium alum (Cs, Rb)Al(SO4)2·12H2O, which yields pure rubidium alum after approximately 30 recrystallisations.[194][195] The limited applications and the lack of a mineral rich in rubidium limit the production of rubidium compounds to 2 to 4 tonnes per year.[194] Caesium, however, is not produced from the above reaction. Instead, the mining of pollucite ore is the main method of obtaining pure caesium, extracted from the ore mainly by three methods: acid digestion, alkaline decomposition, and direct reduction.[194][196] Both metals are produced as by-products of lithium production: after 1958, when interest in lithium's thermonuclear properties increased sharply, the production of rubidium and caesium also increased correspondingly.[10]: 71 Pure rubidium and caesium metals are produced by reducing their chlorides with calcium metal at 750 °C and low pressure.[10]: 74

As a result of its extreme rarity in nature,

Applications

Lithium, sodium, and potassium have many useful applications, while rubidium and caesium are very notable in academic contexts but do not have many applications yet.[10]: 68 Lithium is the key ingredient for a range of lithium-based batteries, and lithium oxide can help process silica. Lithium stearate is a thickener and can be used to make lubricating greases; it is produced from lithium hydroxide, which is also used to absorb carbon dioxide in space capsules and submarines.[10]: 70 Lithium chloride is used as a brazing alloy for aluminium parts.[200] In medicine, some lithium salts are used as mood-stabilising pharmaceuticals. Metallic lithium is used in alloys with magnesium and aluminium to give very tough and light alloys.[10]: 70

Sodium compounds have many applications, the most well-known being sodium chloride as

Potassium compounds are often used as

Rubidium and caesium are often used in

Francium has no commercial applications,

Biological role and precautions

Metals

Pure alkali metals are dangerously reactive with air and water and must be kept away from heat, fire, oxidising agents, acids, most organic compounds, halocarbons, plastics, and moisture. They also react with carbon dioxide and carbon tetrachloride, so that normal fire extinguishers are counterproductive when used on alkali metal fires.[217] Some Class D dry powder extinguishers designed for metal fires are effective, depriving the fire of oxygen and cooling the alkali metal.[218]

Experiments are usually conducted using only small quantities of a few grams in a

Ions

The bioinorganic chemistry of the alkali metal ions has been extensively reviewed.[222] Solid state crystal structures have been determined for many complexes of alkali metal ions in small peptides, nucleic acid constituents, carbohydrates and ionophore complexes.[223]

Lithium naturally only occurs in traces in biological systems and has no known biological role, but does have effects on the body when ingested.

Sodium and potassium occur in all known biological systems, generally functioning as

Potassium is the major

Due to their similar atomic radii, rubidium and caesium in the body mimic potassium and are taken up similarly. Rubidium has no known biological role, but may help stimulate metabolism,[239][240][241] and, similarly to caesium,[239][242] replace potassium in the body causing potassium deficiency.[239][241] Partial substitution is quite possible and rather non-toxic: a 70 kg person contains on average 0.36 g of rubidium, and an increase in this value by 50 to 100 times did not show negative effects in test persons.[243] Rats can survive up to 50% substitution of potassium by rubidium.[241][244] Rubidium (and to a much lesser extent caesium) can function as temporary cures for hypokalemia; while rubidium can adequately physiologically substitute potassium in some systems, caesium is never able to do so.[240] There is only very limited evidence in the form of deficiency symptoms for rubidium being possibly essential in goats; even if this is true, the trace amounts usually present in food are more than enough.[245][246]

Caesium compounds are rarely encountered by most people, but most caesium compounds are mildly toxic. Like rubidium, caesium tends to substitute potassium in the body, but is significantly larger and is therefore a poorer substitute.[242] Excess caesium can lead to hypokalemia, arrhythmia, and acute cardiac arrest,[247] but such amounts would not ordinarily be encountered in natural sources.[248] As such, caesium is not a major chemical environmental pollutant.[248] The median lethal dose (LD50) value for caesium chloride in mice is 2.3 g per kilogram, which is comparable to the LD50 values of potassium chloride and sodium chloride.[249] Caesium chloride has been promoted as an alternative cancer therapy,[250] but has been linked to the deaths of over 50 patients, on whom it was used as part of a scientifically unvalidated cancer treatment.[251]

Notes

- ^ The symbols Na and K for sodium and potassium are derived from their Latin names, natrium and kalium; these are still the origins of the names for the elements in some languages, such as German and Russian.

- ^ Caesium is the spelling recommended by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC).[1] The American Chemical Society (ACS) has used the spelling cesium since 1921,[2][3] following Webster's Third New International Dictionary.

- Roman numeral).[4]

- ^ While hydrogen also has this electron configuration, it is not considered an alkali metal as it has very different behaviour owing to the lack of valence p-orbitals in period 1 elements.

- ^ In the 1869 version of Mendeleev's periodic table, copper and silver were placed in their own group, aligned with hydrogen and mercury, while gold was tentatively placed under uranium and the undiscovered eka-aluminium in the boron group.

- ^ The asterisk denotes an excited state.

- least significant figure(s) of the number prior to the parenthesised value (ie. counting from rightmost digit to left). For instance, 1.00794(7) stands for 1.00794±0.00007, while 1.00794(72) stands for 1.00794±0.00072.[66]

- ^ The value listed is the conventional value suitable for trade and commerce; the actual value may range from 6.938 to 6.997 depending on the isotopic composition of the sample.[58]

- ^ The element does not have any stable nuclides, and a value in brackets indicates the mass number of the longest-lived isotope of the element.[57][58]

- relativistic effects, and this would imply that caesium is the less electronegative of the two.

References

- ISBN 0-85404-438-8. pp. 248–49. Electronic version..

- ISBN 978-0-8412-3999-9.

- (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Royal Society of Chemistry. "Visual Elements: Group 1 – The Alkali Metals". Visual Elements. Royal Society of Chemistry. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ Marggraf, Andreas Siegmund (1761). Chymische Schriften (in German). p. 167.

- ^ du Monceau, H. L. D. (1736). "Sur la Base de Sel Marine". Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences (in French): 65–68. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 38152048.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ISBN 978-3-527-30666-4.

- .

- S2CID 96141217.

- ^ Ralph, Jolyon; Chau, Ida (24 August 2011). "Petalite: Petalite mineral information and data". Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ a b Winter, Mark. "WebElements Periodic Table of the Elements | Lithium | historical information". Archived from the original on 16 October 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-7661-3872-8.

- ^ "Johan Arfwedson". Archived from the original on 5 June 2008. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- ^ a b van der Krogt, Peter. "Lithium". Elementymology & Elements Multidict. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ^ Clark, Jim (2005). "Compounds of the Group 1 Elements". chemguide. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-313-33438-2.

- ^ a b c d Leach, Mark R. (1999–2012). "The Internet Database of Periodic Tables". meta-synthesis.com. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ a b Kaner, Richard (2003). "C&EN: It's Elemental: The Periodic Table – Cesium". American Chemical Society. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- .

- ^ "caesium". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Newlands, John A. R. (20 August 1864). "On Relations Among the Equivalents". Chemical News. 10: 94–95. Archived from the original on 1 January 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ Newlands, John A. R. (18 August 1865). "On the Law of Octaves". Chemical News. 12: 83. Archived from the original on 1 January 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ Mendelejew, Dimitri (1869). "Über die Beziehungen der Eigenschaften zu den Atomgewichten der Elemente". Zeitschrift für Chemie (in German): 405–406.

- ^ doi:10.1021/ed080p952. Archived from the original(PDF) on 11 June 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ a b Fontani, Marco (10 September 2005). "The Twilight of the Naturally-Occurring Elements: Moldavium (Ml), Sequanium (Sq) and Dor (Do)". International Conference on the History of Chemistry. Lisbon. pp. 1–8. Archived from the original on 24 February 2006. Retrieved 8 April 2007.

- ^ a b Van der Krogt, Peter (10 January 2006). "Francium". Elementymology & Elements Multidict. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 8 April 2007.

- ^ "Education: Alabamine & Virginium". Time. 15 February 1932. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2007.

- .

- ^ Adloff, Jean-Pierre; Kaufman, George B. (25 September 2005). Francium (Atomic Number 87), the Last Discovered Natural Element Archived 4 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. The Chemical Educator 10 (5). Retrieved 26 March 2007.

- ISBN 978-0-07-913665-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4020-3555-5.

- ^ PMID 9953034.

- ^ van der Krogt, Peter. "Ununennium". Elementymology & Elements Multidict. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ "Hunt for element 119 set to begin". Chemistry World. 12 September 2017. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ a b c Seaborg, G. T. (c. 2006). "transuranium element (chemical element)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 30 November 2010. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ISBN 978-0-19-960563-7.

- ^ doi:10.1086/375492.

- from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-226-59441-5.

- PMID 16592930.

- ISBN 978-0-521-89148-6.

- ^ "Abundance in Earth's Crust". WebElements.com. Archived from the original on 9 March 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ^ "List of Periodic Table Elements Sorted by Abundance in Earth's crust". Israel Science and Technology Directory. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ "Lithium Occurrence". Institute of Ocean Energy, Saga University, Japan. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- ^ "Some Facts about Lithium". ENC Labs. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- S2CID 93866412.

- S2CID 140585007.

- ^ a b c d e Butterman, William C.; Brooks, William E.; Reese, Robert G. Jr. (2004). "Mineral Commodity Profile: Cesium" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-8493-0474-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-850341-5.

- ^ a b Gagnon, Steve. "Francium". Jefferson Science Associates, LLC. Archived from the original on 31 March 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2007.

- ^ a b Winter, Mark. "Geological information". Francium. The University of Sheffield. Archived from the original on 2 April 2008. Retrieved 26 March 2007.

- ^ "It's Elemental — The Periodic Table of Elements". Jefferson Lab. Archived from the original on 29 April 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ^ a b c Lide, D. R., ed. (2003). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (84th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8053-3799-0. Archivedfrom the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- CODATA reference. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archivedfrom the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ PMID 10035190.

- ISBN 978-0-8014-0333-0.

- .

- ^ Vanýsek, Petr (2011). “Electrochemical Series”, in Handbook of Chemistry and Physics: 92nd Edition Archived 24 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine (Chemical Rubber Company).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Clark, Jim (2005). "Atomic and Physical Properties of the Group 1 Elements". chemguide. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ Gray, Theodore. "Facts, pictures, stories about the element Cesium in the Periodic Table". The Wooden Periodic Table Table. Archived from the original on 28 January 2014. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ The OpenLearn team (2012). "Alkali metals". OpenLearn. The Open University. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ a b Gray, Theodore. "Alkali Metal Bangs". Theodore Gray. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- .

- .

- .

- from the original on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ PMID 12022811.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-85312-027-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-471-97058-3.

- (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Clark, Jim (2005). "Reaction of the Group 1 Elements with Oxygen and Chlorine". chemguide. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ]

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4020-9974-8.

- from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ISBN 978-3-527-33541-1.

- ^ OCLC 179976746. Archived from the originalon 24 July 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2008.

- ^ "Universal Nuclide Chart". Nucleonica. Institute for Transuranium Elements. 2007–2012. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ a b c Sonzogni, Alejandro. "Interactive Chart of Nuclides". National Nuclear Data Center: Brookhaven National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- .

- from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ "Potassium-40" (PDF). Human Health Fact Sheet. Argonne National Laboratory, Environmental Science Division. August 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ National Institute of Standards and Technology (6 September 2009). "Radionuclide Half-Life Measurements". Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ Radioisotope Brief: Cesium-137 (Cs-137). U.S. National Center for Environmental Health

- ^ IAEA. 1988. Archivedfrom the original on 20 January 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ISBN 978-1-870965-87-3.

- ISBN 978-0-13-061142-0.

- ^ a b Clark, Jim (2005). "Reaction of the Group 1 Elements with Water". chemguide. Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-07-023684-4. Section 17.43, page 321

- ISBN 978-1-56670-495-3.

- ^ a b Clark, Jim (2000). "Metallic Bonding". chemguide. Archived from the original on 25 July 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ PMID 25698335.

- ISBN 978-0-471-93623-7.

- ^ "Sodium-Potassium Alloy (NaK)" (PDF). BASF. December 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007.

- ISBN 978-0-471-49315-0. Archived(PDF) from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ ISBN 0-471-93620-0

- ISBN 978-0-470-14549-4.

- ISBN 978-3-642-66620-9.

- PMID 23066852. Archived from the original(PDF) on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-13-175553-6.

- ^ NIST Ionizing Radiation Division 2001 – Technical Highlights. physics.nist.gov

- PMID 27878015.

- PMID 11932511.

- .

- PMID 19750706.

- doi:10.1002/zaac.200300280.. 'Elusive Binary Compound Prepared' Archived 5 October 2008 at the Wayback MachineChemical & Engineering News 80 No. 20 (20 May 2002)

- ISBN 0-471-93620-0

- ISBN 978-1-4097-6995-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-471-18602-1.

- ^ "Welcome to Arthur Mar's Research Group". University of Alberta. 1999–2013. Archived from the original on 4 December 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- .

- .

- S2CID 250883291.

- .

- .

- S2CID 96084147.

- .

- .

- ISBN 978-0-12-356786-4.

- doi:10.2172/4367751. TID-5221. Archivedfrom the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-12-023604-6.

- PMID 11457025.

- ISBN 978-0-471-17560-5.

- .

- ISBN 3-527-29390-6.

- .

- .

- (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Inorganic Chemistry" by Gary L. Miessler and Donald A. Tar, 6th edition, Pearson

- ISBN 978-8122413847.

- ^ "The chemistry of the Elements" by Greenwood and Earnshaw, 2nd edition, Elsevier

- ^ "Inorganic Chemistry" by Cotton and Wilkinson

- ^ from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ Gäggeler, Heinz W. (5–7 November 2007). "Gas Phase Chemistry of Superheavy Elements" (PDF). Lecture Course Texas A&M. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ISBN 978-3-540-07109-9. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- doi:10.1016/0092-640X(77)90010-9. Archived from the original(PDF) on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ Kul'sha, A. V. "Есть ли граница у таблицы Менделеева?" [Is there a boundary to the Mendeleev table?] (PDF). www.primefan.ru (in Russian). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ Kratz, J. V. (5 September 2011). The Impact of Superheavy Elements on the Chemical and Physical Sciences (PDF). 4th International Conference on the Chemistry and Physics of the Transactinide Elements. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ Nuclear scientists eye future landfall on a second 'island of stability' Archived 12 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. EurekAlert! (2008-04-06). Retrieved on 2016-11-25.

- S2CID 120251297.

- ^ PMID 17441140.

- ^ a b "International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry > Periodic Table of the Elements". IUPAC. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ Folden, Cody (31 January 2009). "The Heaviest Elements in the Universe" (PDF). Saturday Morning Physics at Texas A&M. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ Emsley, J. (1989). The Elements. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 22–23.

- ISBN 0-19-855694-2

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Huheey, J.E.; Keiter, E.A. and Keiter, R.L. (1993) Inorganic Chemistry: Principles of Structure and Reactivity, 4th edition, HarperCollins, New York, USA.

- ^ James, A.M. and Lord, M.P. (1992) Macmillan's Chemical and Physical Data, Macmillan, London, UK.

- .

- from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Leach, Mark R. "2002 Inorganic Chemist's Periodic Table". Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- from the original on 13 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ISBN 0-12-352651-5

- ^ S2CID 4199721.

- ^ .

- ^ "Solubility Rules!". chem.sc.edu. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- .

- PMID 11848774.

- .

- .

- doi:10.1107/S0567739476001551. Archived from the original(PDF) on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 7 December 2023. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ISBN 0-85404-438-8. pp. 51. Electronic version..

- .

- ISBN 0-471-64952-X

- ^ Deming HG (1940) Fundamental Chemistry, John Wiley & Sons, New York, pp. 705–7

- ISBN 1-57215-291-5

- ^ Ober, Joyce A. "Lithium" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. pp. 77–78. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 July 2007. Retrieved 19 August 2007.

- ^ Pauling, Linus. General Chemistry (1970 ed.). Dover Publications.

- ^ "Los Alamos National Laboratory – Sodium". Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ^ Merck Index, 9th ed., monograph 8325

- ^ Winter, Mark. "WebElements Periodic Table of the Elements | Potassium | Essential information". Webelements. Archived from the original on 21 November 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-471-23896-6.

- ^ "Cesium | Cs (Element) – PubChem". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 18 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ "WebElements Periodic Table » Rubidium » geological information". www.webelements.com. Archived from the original on 18 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ Liu, Jinlian & Yin, Zhoulan & Li, Xinhai & Hu, Qiyang & Liu, Wei. (2019). A novel process for the selective precipitation of valuable metals from lepidolite. Minerals Engineering. 135. 29–36. 10.1016/j.mineng.2018.11.046.

- .

- ^ a b c d Butterman, William C.; Brooks, William E.; Reese, Robert G. Jr. (2003). "Mineral Commodity Profile: Rubidium" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ^ bulletin 585. United States. Bureau of Mines. 1995.

- ISBN 978-0-471-48494-3.

- .

- ^ from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ a b Price, Andy (20 December 2004). "Francium". Archived from the original on 20 September 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ USGS (2011). "Lithium" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ "Soaps & Detergents: Chemistry". Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-88173-212-2.

- ISBN 978-0-88173-351-8.

- ^ Stampers, National Association of Drop Forgers and (1957). Metal treatment and drop forging.

- ^ Harris, Jay C (1949). Metal cleaning bibliographical abstracts. p. 76.

- ISSN 1083-6160.

- ^ Cordel, Oskar (1868). Die Stassfurter Kalisalze in der Landwirthschalt: Eine Besprechung ... (in German). L. Schnock.

- ISBN 978-0-313-32579-3.

- ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ "Cesium Atoms at Work". Time Service Department—U.S. Naval Observatory—Department of the Navy. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- ^ "The NIST reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty". National Institute of Standards and Technology. 5 February 2015. Archived from the original on 17 April 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Koch, E.-C. (2002). "Special Materials in Pyrotechnics, Part II: Application of Caesium and Rubidium Compounds in Pyrotechnics". Journal Pyrotechnics. 15: 9–24. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-8306-3015-8.

- ^ Winter, Mark. "Uses". Francium. The University of Sheffield. Archived from the original on 31 March 2007. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- ^ a b c Lerner, Michael M. (2013). "Standard Operating Procedure: Storage and Handling of Alkali Metals". Oregon State University. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-87765-472-8.

- ISBN 978-0-935702-48-4.

- ISBN 978-1-903996-65-2.

- ^ Wray, Thomas K. "Danger: peroxidazable chemicals" (PDF). Environmental Health & Public Safety (North Carolina State University). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2011.

- S2CID 5983458.

- PMID 26860299.

- ^ a b c d e Winter, Mark. "WebElements Periodic Table of the Elements | Lithium | biological information". Webelements. Archived from the original on 7 March 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ Gray, Theodore. "Facts, pictures, stories about the element Lithium in the Periodic Table". theodoregray.com. Archived from the original on 27 December 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- PMID 17848039.

- PMID 21301855.

- ^ a b c Winter, Mark. "WebElements Periodic Table of the Elements | Potassium | biological information". WebElements. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ a b Winter, Mark. "WebElements Periodic Table of the Elements | Sodium | biological information". WebElements. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ "Sodium" (PDF). Northwestern University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ "Sodium and Potassium Quick Health Facts". Archived from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- United States National Academies. 11 February 2004. Archived from the originalon 6 October 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- OCLC 738512922. Archived from the original(PDF) on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- PMID 15369026. Archived from the originalon 1 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- S2CID 19315480. Archived from the original(PDF) on 28 January 2012.

- ^ PMID 16253415.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4.

- ISBN 978-1-56053-503-4.

- ^ a b c Winter, Mark. "WebElements Periodic Table of the Elements | Rubidium | biological information". Webelements. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ PMID 13409924.

- ^ S2CID 2574742. Archived from the originalon 9 July 2012.

- ^ a b Winter, Mark. "WebElements Periodic Table of the Elements | Caesium | biological information". WebElements. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- S2CID 33738527.

- doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1943.138.2.246.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ISBN 978-0-7872-7680-5.

- ISBN 978-0-7637-0765-1.

- from the original on 26 November 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ .

- PMID 1154391.

- S2CID 11947121.

- ^ Wood, Leonie. "'Cured' cancer patients died, court told". The Sydney Morning Herald. 20 November 2010. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

![{\displaystyle {\ce {LiR\ +\ Ni(CO)4\ \longrightarrow Li^{+}[RCONi(CO)3]^{-}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b1783ddc7161bab3c63eb4c179496f65fc6ece16)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {Li^{+}[RCONi(CO)3]^{-}->[{\ce {H^{+}}}][{\ce {solvent}}]\ Li^{+}\ +\ RCHO\ +\ [(solvent)Ni(CO)3]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/048a72890ac48383f7155a9f800660ab7b919d38)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {Li^{+}[RCONi(CO)3]^{-}->[{\ce {R^{'}Br}}][{\ce {solvent}}]\ Li^{+}\ +\ RR^{'}CO\ +\ [(solvent)Ni(CO)3]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7ccae3545edde30fdaec9ebc9a5dde6cbd28d06d)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {2 Na \ + H2 \ ->[{\ce {\Delta}}] \ 2 NaH}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/31df93df654a7b734a6adf394ab9bc5b69484a3a)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {2Na\ +\ 2C2H2\ ->[{\ce {150\ ^{o}C}}]\ 2NaC2H\ +\ H2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a763ecb3a7dd778b986b68bdebab4f5b5a28ce7a)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {2Na\ +\ 2NaC2H\ ->[{\ce {220\ ^{o}C}}]\ 2Na2C2\ +\ H2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5dee10d9e2a8694d6b12badfe5ee74aa5e4d66c0)