Divine Comedy in popular culture

The Divine Comedy has been a source of inspiration for artists, musicians, and authors since its appearance in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Works are included here if they have been described by scholars as relating substantially in their structure or content to the Divine Comedy.

The Divine Comedy (Italian: Divina Commedia) is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun c. 1308 and completed in 1320, a year before his death in 1321. Divided into three parts: Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory), and Paradiso (Heaven), it is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature[1] and one of the greatest works of world literature.[2] The poem's imaginative vision of the afterlife is representative of the medieval worldview as it had developed in the Catholic Church by the 14th century. It helped to establish the Tuscan language, in which it is written, as the standardized Italian language.[3]

Literature

Medieval

- In 1373, a little more than half a century after Dante's death, the Florentine authorities softened their attitude to him and decided to establish a department for the study of the Divine Comedy. Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375) was appointed to head the department in October 1373, and he sponsored its organization. In January 1374, Boccaccio wrote and delivered a series of lectures on the Comedy. In addition, Boccaccio is included in the work Origine, vita e costumi di Dante Alighieri, where his treatise Trattatello in laude di Dante provides a biography of Dante.[4]

- Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343–1400) translated, adapted, and explicitly referred to Dante's work.[5]

- "A Complaynt to His Lady," an early short poem, is written in terza rima, the rhyme scheme Dante invented for the Comedy.

- Anelida and Arcite ends with a "compleynt" by Anelida, the lover jilted by Arcite; the compleynt begins with the phrase "So thirleth with the poynt of remembraunce" and ends with "Hath thirled with the poynt of remembraunce," copied from Purgatory 12.32, "la punctura di la rimembranza."

- The House of Fame, a dream vision in three books in which the narrator is guided through the heavens by an otherworldly guide, has been described as a parody of the Comedy. The narrator echoes Inferno 2.32 in the poem (2.588–592).

- The Monk's Tale from The Canterbury Tales describes (in greater and more emphatic detail) the plight of Count Ugolino(Inferno, cantos 32 and 33), referring explicitly to Dante's original text in 7.2459–2462.

- The beginning of the last stanza of Troilus and Criseyde (5.1863-65) is modelled on Paradiso 12.28–30.[6]

Early Modern

- John Milton finds various uses for Dante, whose work he knew well:[7]

- Milton refers to Dante's insistence on the separation of worldly and religious power in Of Reformation, where he cites Inferno 19.115–117.

- Beatrice's condemnation of corrupt and neglectful preachers, Paradiso 29.107–109 ("so that the wretched sheep, in ignorance, / return from pasture, having fed on wind") is translated and adapted in Lycidas 125–126, "The hungry Sheep look up, and are not fed, / But swoln with wind, and the rank mist they draw," when Milton condemns corrupt clergy.

Nineteenth century

- The title of Honoré de Balzac's work La Comédie humaine (the "Human Comedy," 1815–1848) is usually considered a conscious adaptation of Dante's.[8]

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who translated the Divine Comedy into English, wrote a poem titled "Mezzo Cammin" ("Halfway," 1845), alluding to the first line of the Comedy,[9] and a sonnet sequence (of six sonnets) under the title "Divina Commedia" (1867); these were published as flyleaves to his translation.[10]

- Karl Marx uses a paraphrase of Purgatory (V, 13) to conclude the preface to the first edition of Das Kapital (1867), as a kind of motto: "Segui il tuo corso, e lascia dir le genti" ("follow your own road, and let the people talk").[11]

- Lesya Ukrainka's poem "The Forgotten Shadow" (1898) is a feminist reinterpretation of Dante and Beatrice. The forgotten shadow in the poem is Gemma Donati, Alighieri's wife.[12]

Twentieth century

- In E. M. Forster's novel Where Angels Fear to Tread (1905), the character of Gino Carella, upon first introducing himself, quotes the first lines of Inferno[13] (the novel includes several references to Dante's La Vita Nuova as well).[14]

- T. S. Eliot cites Inferno, XXVII, 61–66, as an epigraph to "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" (1915).[15] Eliot cites heavily from and alludes to Dante in Prufrock and Other Observations (1917), Ara vus prec (1920), and The Waste Land (1922).[16]

- Begun in 1916, Cantos take the Comedy as a model.[16]

- Samuel Beckett in his non-fiction essay "Dante... Bruno. Vico.. Joyce", published in Our Exagmination Round His Factification for Incamination of Work in Progress (1929), compares Joyce's reassessments of the conventions of the English language to Dante's departure from Latin and synthesis of Italian dialects in the Divine Comedy.[17]

- In Jorge Luis Borges's 1945 short story The Aleph, the protagonist mourns the recent death of Beatriz Viterbo, whom he loved, at the beginning and meets his cousin Carlos Argentino Daneri, whose name originated from combining Dante Alighieri's name and last name. Also, the Aleph is found in the nineteenth step in the basement, which matches the XIX canto of Paradise, which contains a description similar to that of the Aleph.

- Dante gibi ortasındayız ömrün" ("Age thirty five! It is half of way / We are in the middle of life like Dante") won the Best Turkish Poem Prize in 1946.[18]

- Primo Levi cites Dante's Divine Comedy in the chapter called "Canto of Ulysses" in his novel Se questo è un uomo (If This Is a Man) (1947), published in the United States as Survival in Auschwitz, and in other parts of this book; the fires of Hell are compared to the "real threat of the fires of the crematorium."[19]

- Malcolm Lowry paralleled Dante's descent into hell with Geoffrey Firmin's descent into alcoholism in his epic novel Under the Volcano (1947). In contrast to the original, Lowry's character explicitly refuses grace and "chooses hell," though Firmin does have a Dr. Vigil as a guide (and his brother, Hugh Firmin, quotes the Comedy from memory in ch. 6).[20]

- The seventh and last chapter from Leopoldo Marechal's first novel, Adam Buenosayres (1948), is a parody of the Inferno, entitled "Journey To The Dark City Of Cacodelphia", wherein the titular character meets several of his literary contemporaries (including his guide).[21]

- Poet Derek Walcott, in 1949, published Epitaph for the Young: XII Cantos, which he later acknowledged as influenced by Dante.[16]

- Jorge Luis Borges, who wrote extensively about Dante,[16][22] included two short texts in his Dreamtigers (El Hacedor, 1960): "Paradiso, XXXI, 108" and "Inferno, I, 32," which paraphrase and comment on Dante's lines.[23][24]

- African-American author LeRoi Jones, in 1965, published the novel The System of Dante's Hell, in which a young African-American man lives nomadically in the Southern United States, struggling with segregation and racism. The book correlates the man's experience with Dante's Inferno, and includes a diagram of the fictional hell described by Dante.

- The First Circle (1968) takes its title from the Inferno. Set in a special Gulag for scientists, it parallels Dante's First Circle (Limbo) where virtuous philosophers of antiquity are separated from God and humanity but not punished in any other way.[25]

- James Merrill published his Divine Comedies, a collection of poetry, in 1976; a selection in that volume, "The Book of Ephraim", consists "of conversations held, via the Ouija board, with dead friends and spirits in 'another world.'"[26]

- Authors Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle wrote a modern sequel to the Inferno, Inferno (1976), in which a science fiction author dies during a fan convention and finds himself in Hell, where Benito Mussolini functions as his guide. They wrote a subsequent sequel to their own work, Escape from Hell (2009).[27][28]

- Gloria Naylor's Linden Hills (1985) uses Dante's Inferno as a model for the trek made by two young black poets who spend the days before Christmas doing odd jobs in an affluent African American community. The young men soon discover the price paid by the inhabitants of Linden Hills for pursuing the American dream.[29]

- Author Monique Wittig's Virgile, Non (published in English as Across the Acheron, 1985) is a lesbian–feminist parody of the Divine Comedy set in the utopia/dystopia of second-wave feminism.[30]

- Mark E. Rogers used the structure of Dante's hell in his 1998 comedic novel Samurai Cat Goes to Hell (the last in the Samurai Cat series), and includes the trope of a gate to hell with an "abandon hope" inscription.[31]

Twenty-first century

- Irish poet Irish Times (18 January 2000) that begins with a translation of Paradiso 33.58–61 as "Like somebody who sees things when he's dreaming / And after the dream lives with the aftermath / Of what he felt, no other trace remaining, / So I live now".[32][33]

- Nick Tosches's In The Hand of Dante (2002) weaves a contemporary tale about the finding of an original manuscript of the Divine Comedy with an imagined account of Dante's years composing the work.[34]

- Inferno by Peter Weiss (written in 1964, published in 2003) is a play inspired by the Comedy, the first part of a planned trilogy.[35]

- Boston, who must also investigate murders being committed based on the punishments in the text, due to their desire to protect Dante's reputation and the fact that only they have the necessary expertise to understand the murderer's motivations.[34]

- Óscar Esquivias in his trilogy of novels Inquietud en el Paraíso (2005), La ciudad del Gran Rey (2006) and Viene la noche (2007) shows his personal vision of Dante's Divine Comedy.[36]

- In the novel The Tenth Circle (2006) by Jodi Picoult, the main character's comic strip, The Tenth Circle, is based on the Inferno.[37]

- Dante himself is a character in The Master of Verona (2007), a novel by David Blixt that combines the people of Dante's time with the characters of Shakespeare's Italian plays.[38]

- Dale E. Basye's book series Heck: Where the Bad Kids Go (began in 2008) features a modified version of the nine circles of hell.

- S.A. Alenthony's novel The Infernova (2009) is a parody of the Inferno as seen from an atheist's perspective, with Mark Twain acting as the guide.[39]

- The title of Yann Martel's 2010 novel The Divine Comedy.

- Sylvain Reynards' 2011 novel Gabriel's Inferno was inspired by the relationship between Dante and Beatrice.[40]

- Dante Quintana from Benjamin Alire Sáenz's 2012 novel Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe is named after Dante.

- Laura Elizabeth Woollett's 2014 novel The Wood of Suicides is named after the second ring of the seventh circle of hell.

- Adam Roberts' Purgatory Mount is a 2021 science fiction novel that features a huge mountain on a distant planet resembling Dante's Mount Purgatory.[41]

Visual arts

Sculpture

- Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux's sculpture Ugolino and His Sons is based on the account of Count Ugolino in Inferno Canto XXXIII.

- Auguste Rodin's sculptural group The Gates of Hell draws heavily on the Inferno. The component sculpture, Paolo and Francesca, represents Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta, whom Dante meets in Canto 5.[42] The version of this sculpture known as The Kiss shows the book that Paolo and Francesca were reading. Other component sculptures include Ugolino and his children (Canto 33) and The Shades, who originally pointed to the phrase "Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch'entrate" ("Abandon all hope, ye who enter here") from Canto 3.[42] Sculptures of Grief and Despair cannot be assigned to particular sections of the Inferno, but are in keeping with the overall theme. The famous component sculpture The Thinker, near the top of the gate, and also produced as an independent work, may represent Dante himself.[42]

- Timothy Schmalz created a series of 100 sculptures, one for each canto, on the 700th anniversary of the date of Dante’s death.[43]

Illustrations

- Giovanni di Paolo illuminated Dante's Paradiso with 61 miniature tempera paintings in the 1440s.[44]

- Lorenzo Pierfrancesco de' Medici; Botticelli also designed a series of illustrations for the 1481 edition of the poem.[45]

- Stradanus prepared a series of illustrations of Inferno.[46]

- A commentary by La Comedia di Dante Alighieri con la nova esposizione written by Alessandro Vellutello and printed in 1544 by Francesco Marcolini, was illustrated with 87 engravings, possibly by Giovanni Britto.[47]

- John Flaxman's set of one hundred and eleven illustrations were influential across Europe on artists such as Goya and Ingres, because of their radically minimalist style.[48]

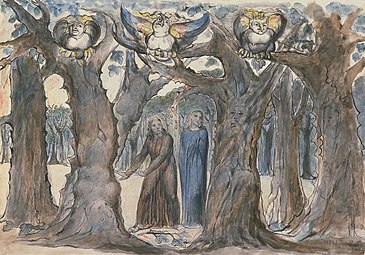

- watercolour illustrations to the Divine Comedy, including The Wood of the Self-Murderers: The Harpies and the Suicides. Though he did not finish the series before his death in 1827, they offer a powerful visual interpretation of the poem.[49]

- Gustave Doré made the most famous illustrations in the 19th century; the plates were drawn in 1857, and published in 1860 with Henry Francis Cary's translation.[50]

- Franz von Bayros illustrated a 1921 edition in colour.[51]

- Salvador Dalí made a series of prints for the Comedy in 1950–51.[52][16]

- British artist Tom Phillips illustrated his own translation of the Inferno, published in 1985, with four illustrations per canto.[53]

-

Paradiso: Dante and Beatrice meet Folco of Marseille, who denounces corrupt churchmen. Giovanni di Paolo, 1444–1450

-

Paradiso, Canto IX. Sandro Botticelli, 1485–1490

-

Gli arroncigliò le impegolate, Inferno, Canto XXII. John Flaxman, 1793

Painting

- King Minos as they are described in the Inferno.

- Styx.[54]

- Joseph Anton Koch illustrated Dante's Divine Comedy and in the period 1824–1829 painted the four frescoes in the Dante Room of Casa Massimo.[55]

- William-Adolphe Bouguereau, the prolific 19th-century academic artist, painted Dante And Virgil In Hell in 1850.[56]

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a Pre-Raphaelite, made several paintings of the Divine Comedy, including Dante's Vision of Rachel and Leah (1855, for Purgatorio XXVII), Pia de' Tolomei, his largest painting Dante's Dream at the Time of the Death of Beatrice (1871), and Beata Beatrix (1872).[57]

- Henry Holiday is best known for his 1884 painting Dante and Beatrice.[58]

- Graba' made a cycle La Divina Commedia consisting of 111 paintings in 2003 exhibited in the Art Hall Sint-Pietersabdij in Ghent.[59][60]

- Luke Chueh made a series of paintings based on the Inferno in 2009 exhibited in Gallery 1988.[61]

-

Dante and Virgil in the Inferno. Fresco in Casa Massimo, Joseph Anton Koch, 1825-1828

-

Dante and Beatrice. Henry Holiday, 1884

Architecture

- The Palacio Barolo in Buenos Aires, completed in 1923, was designed in accordance with the cosmology of Dante's Divine Comedy, motivated by Italian architect Mario Palanti's admiration for Dante.[62]

- The Danteum is an unbuilt monument designed by the Italian modernist architect Giuseppe Terragni in 1938 at the behest of Benito Mussolini's fascist dictatorship.[63]

Performing arts

Dance

- Dante and Beatrice in "Paradiso", the final section of The Dante Project, 2021In 2021, the Royal Opera House put on The Dante Project, choreographed by Wayne McGregor to new music composed and conducted by Thomas Adès, with set and costumes by Tacita Dean. It was danced by The Royal Ballet, led by its principal dancer Edward Watson as Dante, in his final appearance after 20 years working with and interpreting McGregor. The music was performed live by an orchestra of 75 musicians. Sarah Crompton called the work "bold, beautiful, emotional and utterly engaging".[64] The dance is in three sections. "Inferno" shows Dante's journey to hell, guided by Virgil, in "remarkably free and inventive"[64] choreography, "rich in feeling".[64] "Purgatorio" shows Dante meeting two incarnations of his young self, and three of the woman he loves, Beatrice. Watson dances with the living Beatrice (Francesca Hayward) "in lovely, poetic flow",[64] and then with the heavenly Beatrice (Sarah Lamb) "all unfolding limbs and ethereal gestures".[64] "Paradiso" has Dante in heaven with the dancers skittering about the stage all in white, in what Crompton calls a mood "of abstracted joy, deep but dazzling".[64]

Opera

- In Claudio Monteverdi's 1607 opera L'Orfeo, the title character is bombarded with the famous line Lasciate ogni speranza voi ch'entrate[65] as he attempts to enter the underworld.

- Gaetano Donizetti's 1837 opera Pia de' Tolomei centers around the life of the titular Pia de' Tolomei as mentioned in Purgatorio Canto XIII.[66]

- Numerous mainly 19th century operas treat the story of Francesca da Rimini, many of them including those by Pellico (1818), Strepponi (1823), Carlini, Mercadante, Quilici, Generali, Staffa, Manna, Fournier, Tamburini, Borgatta, Morlacchi, Papparlardo, Nordal, Maglioni, Bellini, DeVasinis, Meiners (1841), Cannetti, Brancaccio, Rolland, Ruggieri, Pinelli, Franchini, Meiners (again, this time in 1860), Gilson, Sescewich, Boullard, Marcarini, Moscuzza, Goetz, Cagnoni, Thomas, Impallomeni, Gilson, Nápravník, Rachmaninov (in 1906), Leoni, Zandonai (1914, based on the 1901 play by Gabriele D'Annunzio), and Henried (in 1920) all having that same title.[67]

- Benjamin Godard's Dante et Béatrice from 1890 depicts Dante not as a famous poet, but as a young man implicated in political and love intrigues in his quest for Beatrice.[68]

- Il Tabarro and Suor Angelica, centers around an incident concerning the titular Gianni Schicchi de' Cavalcanti mentioned in Inferno Canto XXX.[69]

- Louis Andriessen's 2008 opera La Commedia is a retelling of The Divine Comedy.[70]

- Lucia Ronchetti's 2021 opera Inferno is based on the Inferno section of The Divine Comedy. Its libretto consists mostly of Dante's original writing as compiled by the composer.[71]

Classical music

By 1995, the Divine Comedy had been set to music over 120 times; Gioacchino Rossini created two such settings. Only 8 of the settings are of the complete Commedia, "the most famous"[67] being Liszt's symphony; others have composed music for some of Dante's characters, while yet others have set passages of the Commedia to music.[67]

- Franz Liszt's Symphony to Dante's Divina Commedia (completed 1856) has two movements: "Inferno" and "Purgatorio." A concluding "Magnificat" is included at the end of the "Purgatorio" movement and replaces the planned third movement, which was to be called "Paradiso" (Liszt was dissuaded by Richard Wagner from his original plan).[72] Liszt also composed a Dante Sonata (started 1837, completed 1849).[73]

- Pyotr Ilich Tchaikovsky's 1876 Francesca da Rimini (subtitled "Symphonic Fantasy After Dante") is a symphonic poem based on an episode in the fifth canto of the Inferno.[74]

- The text of the short prayer from the opening lines of Canto 33 of Paradiso was set to music for a cappella women's voices by Giuseppe Verdi. Composed between 1886 and 1888, "Laudi alla Vergine Maria" (Praises to the Virgin Mary), the third movement of his Four Sacred Pieces[75] was one of the last pieces written before his death.

- Henry Barraud's cantata for five voices and 15 instruments, La divine comédie, based on Dante's text, was composed in 1972.[76]

- Dutch composer Vondel and the Old Testament, in addition to The Divine Comedy. The five parts are "The City of Dis, or The Ship of Fools", "Racconto dall'Inferno", "Lucifer", "The Garden of Delights", and "Luce Etterna".[77]

Popular music

- The song "Canto IV (Limbo)" from Progressive music group Discipline's 1997 album Unfolded Like Staircase describes the sorrow of those souls who never knew a deity.[78]

- Tangerine Dream has released albums setting all the three parts of The Divine Comedy to music: Inferno is a recording of a live performance at the St Marien zu Bernau Cathedral in 2001, and Purgatorio and Paradiso are studio albums from 2004 and 2006 respectively.[79]

- German

- Brazilian metal band Sepultura’s 2006 album Dante XXI is a concept album based on the Divine Comedy, which lead vocalist Derrick Green had read in high school and suggested to the band.[82]

- American progressive metal band Symphony X's 2015 album Underworld is based on the Inferno.[83][84]

- American singer-songwriter Ethel Cain's debut album Preacher's Daughter (2022) contains the song "Ptolomaea", named after one of the four concentric rings of the Ninth Circle of Hell, as depicted in the Inferno.[85]

- Irish Musician Hozier's third studio album Unreal Unearth (2023) is inspired by Inferno. Each song signifies Dante's journey through one of the nine circles of Hell and his ascent on the other side.[86]

- Canadian singer-songwriter The Weeknd has confirmed that his 3 studio albums After Hours (2020), Dawn FM (2022), and Hurry Up Tomorrow (2025) are part of a trilogy and has hinted that the trilogy is an adaptation of the Divine Comedy with each album representing a different part of the poem (Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso)

Radio

- Inferno Revisited, a modernised interpretation of Dante written by Peter Howell, was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on 17 April 1983.[87]

- Between March and April 2014, the BBC adapted The Divine Comedy for Radio 4, starring Blake Ritson and John Hurt playing younger and older versions of Dante.[88]

Film

- The 1911 L'Inferno was directed by Giuseppe de Liguoro, starring Salvatore Papa.[89] It was released on DVD in 2004, with a soundtrack by Tangerine Dream.

- The 1924 L'Inferno; the section on the inferno is reduced to a ten-minute segment.[90]

- The 1935 motion picture Dante's Inferno, directed by Harry Lachman, written by Philip Klein and starring Spencer Tracy, is about a fairground attraction based on Inferno. The film features a 10-minute fantasy sequence visualizing Dante's Inferno.

- The 1975 Pier Paolo Pasolini film Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom is set in four segments inspired by Dante's Divine Comedy: the Anteinferno, the Circle of Manias, the Circle of Shit and the Circle of Blood.[91]

- Stan Brakhage's eight-minute hand-painted film, The Dante Quartet (1987), is inspired by the Divine Comedy.[92]

- Peter Greenaway adapted Cantos I to VIII for BBC Two as A TV Dante (1987–1990).[93]

- The Three Colors Trilogy (1993–1994). This intention, however, was abandoned after his death in 1996 until Tom Tykwer decided to shoot the film Heaven in 2002, using Kieslowski's original screenplay.[94] In 2005, Bosnian director Danis Tanović directed Hell (French) based on Kieslowski's screenplay sketches. The screenplay was completed by Krzysztof Piesiewicz, Kieslowski's screenwriter.[95]

- The motion picture Se7en (1995) stars Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman as two detectives who investigate a series of ritualistic murders inspired by the seven deadly sins. The film makes many references to Dante's Divine Comedy.[96]

- Ridley Scott's 2001 film Hannibal has Hannibal Lecter as a medievalist lecturing on Dante's Divine Comedy, and to some extent echoing the work in his murderous methods.[97]

- Jean-Luc Godard's 2004 film Notre musique is structured in three parts, Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise respectively, alluding to the Divine Comedy.[98]

- The film

- The 2015 Chinese documentary Behemoth (Chinese: 悲兮魔兽; pinyin: bēixī móshòu), directed by Zhao Liang, is loosely based on Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy and is about the environmental, sociological, and public health effects of coal-mining in China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.[101]

- The 2016 mystery thriller Inferno makes many references to The Divine Comedy and to the Divine Comedy Illustrated by Botticelli including hiding a word puzzle in a version of the painting Map of Hell with the levels of Hell rearranged. There's a clue in an email that refers to a passage from Paradiso and the virus that serves as the catalyst for the film's plot is named "Inferno."[102]

- The 2018 film The House That Jack Built features Matt Dillon as protagonist Jack, a serial killer who believes that his murders are a piece of art, similar to the Divine Comedy. Jack encounters Virgil, or Virg, as he calls him, as a hallucination portrayed by Bruno Ganz, (well known from his role as Adolf Hitler in 2004's Downfall). Jack carries on a commentary with Virgil throughout the film sometimes expressing his desire of becoming an architect despite being an engineer. Jack ends up wearing Dante Alighieri's red robe while unsuccessfully attempting to escape Inferno after rejecting Virg's advice to follow him into Purgatorio, the only safe way of reaching the destination of Paradiso.[103]

- The 2020 film Friend of the World references The Divine Comedy and begins with a direct quote by Dante Alighieri.[104]

Graphic media

Animations, comics and graphic novels

- Manga series Demon Lord Dante from Go Nagai (1972, rebooted in 2002) was inspired by the Gustave Doré illustrations of The Divine Comedy.[106]

- Ty Templeton parodied Dante in his comic book Stig's Inferno (1985-1986).[107][108]

- The Sandman comic series, running from January 1989 to March 1996, features a heavily Dante-inspired Hell, including the Wood of Suicides, the Malebolge, and the City of Dis; Lucifer is imprisoned in Hell.[110] Mike Carey's spin-off series Lucifer, also from DC/Vertigo Comics, was based on characters from The Sandman. It features aspects of a Dante-inspired Hell and Heaven, particularly the Primum Mobile and the Nine Sections.[111]

- Todd McFarlane's Spawn supervillain Malebolgia (Spawn #1, May 1992) is named after the Malebolge.

- In the 1996 Spanish comic El infierno, part of the Superlópez series, the titular character travels to Hell to prevent a demonic contract from being fulfilled. The search reveals a structure identical to the one in the Divine Comedy. Dante is also namedropped many times in the album.[112]

- Dante's Inferno: The Graphic Novel (2012) by Joseph Lanzara utilizes Gustave Doré's 1857 illustrations of the Divine Comedy in the form of a comic book inspired by the poem.[113]

- The Cartoon Network's debut miniseries, Over the Garden Wall (November 2014), corresponds to the structure of the Inferno; it stars a lost poet guided by a woman named Beatrice.[114]

- Cerebus, Cerebus in Hell? (2017) satirically utilizes Gustave Doré's engravings for the Divine Comedy as backgrounds and plot devices.[105]

- Paul and Gaëtan Brizzi made Dante's Inferno: A Graphic Novel Adaptation, which was published in 2023.[115]

Video games

- Artificial Mind and Movement for release on the PlayStation Portable. The story is loosely based on Dante's Inferno.[citation needed]

- Dante's Inferno is a series of six comic books based on the same video game. Published by WildStorm from December 2009 through May 2010, the series was written by Christos Gage with art by Diego Latorre.[117]

- animated film released on February 9, 2010. The film is also a spin-off from Dante's Inferno.[citation needed]

- Dante's Inferno is a series of six

- The video game Ultrakill is partially inspired by Dante's Inferno, with the games setting being a Hell divided into distinct layers like in the Divine Comedy. Though some layers, like Limbo and Wrath, share themes with The Divine Comedy's version of Hell, some, such as Greed, present ideas not originating from Dante's Inferno.

- Limbus Company is a 2023 gacha game developed by South Korean studio Project Moon. The protagonist, a manager referred to as "Dante", has a guide named "Vergilius". The game is divided into sections named after parts of The Divine Comedy (as of current, only Inferno has been reached), with its chapters being referred to as "Cantos".[118]

Tabletop role-playing games

Several aspects of the Divine Comedy could have influenced many tabletop role-playing games: visiting ordered parallel worlds on a planar crawl, a gamified progression by trials and levels towards salvation, or using deciphered symbolism to acquire knowledge that gives more power to characters.[119]

- The Nine Hells after locations in Dante's Inferno.[120] The game borrowed the name "malebranche" for one diabolical race, although the original write-up mistranslated that word as "evil horn".[121]

- The Planescape setting, in particular, borrows many elements from the book (some wholesale, some piecemeal), and much of the expanded cosmology, with dimensions for the dead based on alignment and most dimensions having many separate layers, are inspired by those seen in the Inferno. The planecrawling gameplay of Planescape and early setting of D&D could be heavily inspired by the structured travel of Dante through the layers of the planes of the Divine Comedy.[119]

- Acheron Games published Inferno, a tabletop role-playing game heavily inspired by the depiction of hell as found in the Divine Comedy.[122]

Web Originals

- One of the food items listed in SCP-261's experiment log is a package of nine distinct circular, concentric biscuits labeled "Dante's", and the tagline on the packaging reads "Tastes like hell!".[123]

Notes

- ^ For example, Encyclopedia Americana, 2006, Vol. 30. p. 605

- ISBN 9780151957477.

- ^ See Lepschy, Laura; Lepschy, Giulio (1977). The Italian Language Today. or any other history of Italian language.

- ISBN 978-0-631-22852-3.

- ISBN 978-0-521-42742-5.

- ISBN 0-395-29031-7.

- ISBN 0-521-42742-8. 241–244.

- ^ Robb, Graham. Balzac: A Life. New York: Norton, 1996. P. 330.

- ISBN 978-0-8135-3162-5.

- ISBN 978-1-57958-008-7. p. 269.

- ISBN 978-0-14-044568-8.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-554-68727-8.

- ISBN 978-0-8044-6893-0.

- ISBN 978-0-226-25888-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-631-22852-3.

- ISBN 978-0-811-20446-0.

- ISBN 978-9755100173.

- ISBN 978-0-312-23301-3.

- ISBN 978-0-8203-1826-4.

- ISBN 9780773543096.

- ISBN 978-0-8223-1117-1.

- ISBN 978-0-292-71549-3.

- ISBN 978-0-19-866114-6.

- ^ The First Circle by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Retrieved 29 December 2021 – via LibraryThing.

- ^ Vendler, Helen (1979-05-03). "James Merrill's Myth: An Interview". The New York Review of Books. 26 (7). New York.

- ISBN 0-521-42742-8. 255.

- ISBN 978-0-7653-1676-9.

- ISBN 0-521-42742-8.

- S2CID 164412541.

- ISBN 978-0-312-86642-6.

- ISBN 978-0-631-22852-3.

- ^ Heaney, Seamus (21 December 1999). "A Dream of Solstice". The Irish Times. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-631-22852-3.

- ^ "Inferno by Peter Weiss". The Complete Review. 2008. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- ^ Fernando Castanedo (2006). "Dante en Burgos (1936)". El País. El País, 21 January 2006. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ Picoult, Jodi (2006-03-17). "Book 13: The Tenth Circle". Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- ^ Wisniewski, Mary (2007-11-04). "'Master' class; Chicago actor gives readers a delightful romp through the backstory of Romeo & Juliet". Chicago Sun-Times. p. B9.

- ISBN 978-0-9819678-9-9.

- ^ "How long can the rich and famous 'Gabriel's Inferno' author stay anonymous?". Macleans.ca. 2012-09-11. Retrieved 2023-07-06.

- ISSN 0047-4959. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ ISBN 2-901428-69-X.

- The Florentine.

- ^ Biggs, Sarah (8 March 2013). "To Hell and Back: Dante and the Divine Comedy". British Library. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ "Botticelli's Designs". Renaissance Dante in Print (1472–1629). Archived from the original on 2010-06-11. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ^ "The Most Harrowing Paintings of Hell Inspired by Dante's Inferno". Dante Today. 26 September 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ "The World of Dante". www.worldofdante.org. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ISBN 978-0486455587.

- Tate Gallery. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ Roosevelt, Blanche (1885). Life and Reminiscences of Gustave Doré. New York: Cassell & Company. p. 215.

- ^ "Franz von Bayros Illustrations". Syracuse University Libraries. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ "The Divine Comedy – Salvador Dali".

- ^ Fugelso, Karl (2011). "Tom Phillips' Dante". In Richard Utz; Elizabeth Emery (eds.). Cahier Calin: Makers of the Middle Ages. Essays in Honor of William Calin. Studies in Medievalism. Kalamazoo, Michigan: not stated. pp. 62–64.

- ISBN 978-0-333-23583-6.

- ^ Bellonzi, Fortunato (1970). "Koch, Joseph Anton". Treccani. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ISBN 978-1904832775.

- ^ "Dante Gabriel Rossetti [exhibition] 16 Oct 2003—18 Jan 2004". Liverpool Museums. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ "'Dante and Beatrice', Henry Holiday, 1884". National Museums Liverpool. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ George, Jasmine (15 November 2020). "Selections from Graba''s 2003 Divina Commedia". Dante Today. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ "2003 Divina Commedia (see the 3 tabs for Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso)". Graba.be. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ "LUKE CHUEH : INFERNO". lukechueh.com. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ "Restauran el Palacio Barolo, una joya de la arquitectura". Clarin.com. 2003-10-18. Retrieved 2009-01-22.

- ^ Schumacher, Thomas L. (1983). Terragni e il Danteum 1938 [Terragni and the Danteum 1938] (in Italian). Roma: Officina Edizioni. p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e f Crompton, Sarah (24 October 2021). "The Dante Project review – bold, beautiful and utterly engaging". The Observer. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "Abandon hope all ye who enter"

- The Divine Comedy, "Purgatorio", Canto V, vv.130–136 "Pia de' Tolomei".

- ^ JSTOR 40166513.

- ^ Maria Ann Roglieri Dante and Music: Musical Adaptations of the Commedia 2001 "Benjamin Godard's Dante et Beatrice, like Carrer's opera, is a fantasy. Godard's work also features a full-blown romance between Dante and Beatrice but includes a slightly more coherent and comprehensive treatment of Dante's text"

- ISBN 0-226-29757-8.

- ^ Swed, Mark (20 June 2008). "'Commedia' is more than a little divine". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ Sandner, Wolfgang (29 June 2021). "Oper "Inferno" in Frankfurt : Klänge sichtbar machen". FAZ (in German). Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Greenberg, Robert (7 November 2016). "Franz Liszt's Dante Symphony". Robert Greenberg Music.

- ISBN 0-521-46963-5.

- ISBN 978-0-13-601970-1.

- ^ Sacred Pieces

- ^ "La Divine Comédie – Henry Barraud". Dante Today. 24 August 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ "Louis Andriessen – La Commedia – Opera". boosey.com. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ^ "Iced Earth re-record "Dante's Inferno" and give it away for free | The Official Iced Earth Website". Icedearth.com. September 5, 2011. Archived from the original on May 23, 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ^ Froese-Acquaye, Bianca. "Dante - the Electronic Opera by Tangerine Dream". Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ Parrish, Peter (28 September 2004). "yelworC: Trinity: Metropolis, 2004". Stylus Magazine. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Huhn, Sebastian (25 October 2007). "yelworC - Icolation". Reflections of Darkness music magazine. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Rand, Odd Inge (March 14, 2006). "SEPULTURA - Dante XXI". Metal Express Radio. Retrieved March 2, 2025.

- ^ Roques, Alice (18 July 2015). "Interview: Symphony X". Rock Revolt. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ Dare, Tom (12 August 2015). "Russell Allen on the spiritual journey of playing live with Symphony X". Metal Hammer. Team Rock. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ Daw, Stephen (2022-05-12). "The Book of Ethel Cain: How the Alternative Phenom Built Up Her Own Reality Only to Tear It Down". Billboard. Retrieved 2023-12-27.

- ^ "Inside Hozier's 'Unreal Unearth': How The Singer Flipped Dante's 'Inferno' & The Irish Language Into His Latest Album". grammy.com. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "Inferno Revisited: BBC Radio 4". BBC. 17 April 1983. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "Classic Serial: Dante Alighieri - The Divine Comedy". BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ISBN 0-8020-8827-9.

- OCLC 1083765034.

- ISBN 978-1-317-28249-5.

- ^ "The Dante Quartet". Canyon Cinema. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "A TV Dante The Inferno: Cantos I-viii (1989)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (18 October 2002). "Heaven". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (21 April 2006). "Hell (L'Enfer)". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- JSTOR 43263574.

- ^ Saiber, Arielle (15 September 2006). ""Hannibal" (Ridley Scott, 2001)". Dante Today. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (2 October 2004). "A Godard Odyssey in Dante's Land". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ Curt Holman (2007-04-18). "Skimming the cream of the Atlanta Film Festival crop". CreativeLoafing.com. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ^ Kevin Stewart (2007-04-15). "Atlanta Film Festival '07: Capsule Previews". CinemaATL.com. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ^ Kues, Sabine (12 September 2015). "VENICE 2015 Competition: Behemoth: The beast that is civilisation". Cineuropa. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ Lodge, Guy (8 October 2016). "Film Review: 'Inferno'". Variety magazine. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Hayes, Britt (3 December 2018). "'The House That Jack Built' Spoiler Review: A Deep Dive Into 2018's Most Polarizing and Controversial Film". /Film. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ Parker, Sean (10 May 2022). "Friend of the World: The Divine Comedy of Body Horror". Horror Obsessive. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022.

- ^ a b MacDonald, Heidi (27 June 2016). "Exclusive: More on Cerebus in Hell? and The Beat's very own personalized Cerebus comic strip". Comics Beat. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ Prisco, Francesco (April 27, 2007). "Go Nagai, il padre di Goldrake: "Devilman? E' figlio del Lucifero di Dante"" [Go Nagai, the father of Goldrake: "Devilman? The son of Dante's Lucifer"]. Il Sole 24 Ore (in Italian). Archived from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ Israel, D. N. "Ty Templeton, "Stig's Inferno" (1980s)". Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ Templeton, Ty. "Stig's Inferno". Ty Templeton. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

The entire series is now available free online.

- ^ [1] Archived 2006-09-10 at the Wayback Machine[2]

- ^ "The Sandman and Dante's Inferno". Dante Today. 26 August 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ "Osprey Journal". 2021-12-30. Archived from the original on 2021-12-30. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ El Infierno in La Página Escarolitrópica Gmnésica De Superlópez (in Spanish)]

- ISBN 978-0-9639621-1-9.

- ^ "Over the Garden Wall (2014) - Dante Today - Citings & Sightings of Dante's Works in Contemporary Culture". 2022-12-06. Archived from the original on 2022-12-06. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ Cassel, Benoît (21 January 2023). "L'Enfer de Dante". PlanèteBD (in French). Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Kiyohide Ino (November 1992). "BASIC Magazine News". Micom BASIC Magazine (in Japanese). No. 125. The Dempa Shimbunsha Corporation. p. 209. Retrieved 2022-10-03.

- ^ "Dante's Inferno #1". dccomics.com. DC Entertainment. December 2009. Retrieved 2018-10-25.

- ^ "Dante's La Commedia Divina and Its Lasting Impact on Modern Culture". carolinianuncg.com. The Carolinian. October 24, 2023. Retrieved 2025-01-21.

- ^ a b Martinolli, Pascal (10 September 2021). "Dante's Inferno in tabletop role-playing games". ZOtRPG !. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ Gygax, Gary (1977). "Planes: The Concepts of Spatial, Temporal and Physical Relationships in D&D". Dragon magazine. No. 8. p. 4.

- ISBN 0-935696-00-8.

- ^ "Inferno | Acheron Games - MADE IN ITALY. SHARED WORLDWIDE". Acheron Games - MADE IN ITALY. SHARED WORLDWIDE. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ "Experiment Log 261 Ad De - SCP Foundation". The SCP Foundation. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

External links

- 700 Years of Dante's Divine Comedy in Art – documented image collection on The Public Domain Review