Earth in culture

The

Etymology

Unlike the other planets in the Solar System, in English, Earth does not directly share a name with an ancient Roman deity.

Planetary symbol

The standard

Religious beliefs

Earth has often been personified as a

Creation myths in different cultures and religions

Babylonian

Tiāmat is a sea monster known as the monster of monsters. She is killed and her body is cut in half in order to create heaven and Earth. The upper part of Tiāmat is used to create heaven with her belly as the separation line. The lower part of her body was used to create Earth, but the way that specific body parts were used to create other things is not described.[18]

Norse

Aztec

In the myth of the god

Yoruba

In the Yoruba religion, there are many gods, but the First Father is called Olorun and he is said to be perfect. Before earth was created there was only sky above and water, swamps, and mist below. One day one of the gods named Olbatala asked Olorun if he could make a world out of what was below. Olorun granted him permission to make a world from the things down below. Before taking action, Obatala consulted with another god named Orunmila (the god of divination) who told Obatala to get a golden chain and lower it from the sky to the waters below so that he could eventually return to the other gods. Orunmila also told him to take a snail shell with soil in it, a hen, a black cat, and a palm nut. Obatala heeded the god of divination’s words and descended the golden chain with all of the things he was told to take. Once Obatala reached the waters below he poured all of the soil onto the water. He then set the hen down which spread the soil out by pecking and scratching at it. After the soil was spread, he planted the palm nut which grew and produced more nuts which respectively grew more trees. Obatala thought that this new world needed more light, so he consulted with Olorun who then created the Sun and Moon and sent fire on a vulture’s head for light when the Sun was gone. Obatala got lonely on this new world of his, so he fashioned human beings out of clay and asked the First Father for help. Olorun breathed life into the clay figures and humans became living. Olorun also gave life to animals, plants, rivers, and language for the people to utilize. When Obatala was pleased with his work he climbed back up the golden chain and lived with the other gods in the sky above.[22]

In fiction

While in general, a planet can be considered "too large, and its lifetime too long, to be comfortably accommodated within fiction as a topic in its own right", this has not prevented some writers from engaging with the topic (for example, Camille Flammarion's Lumen (1887), David Brin's Earth (1990), or Terry Pratchett's, Ian Stewart's and Jack Cohen's The Science of Discworld (1999)[23]).[24] The iconic photo of Earth known as The Blue Marble, taken by the crew of Apollo 17 (1972), and similar images of Earth from space, might have popularized Earth as a theme in fiction.

Additionally, it is undeniable that an overwhelming majority of fiction is set on or features the Earth.

Depiction of Earth

In the ancient past there were varying levels of belief in a

-

The Imago Mundi, the oldest known world map, made no earlier than the 9th century BC Babylonia. Now in the British Museum.

-

Diagram illustrating the major categories of European classicalmappae mundi.

-

Leonardo da Vinci's world map in eight Reuleaux triangle octants (1503)

-

Title page ofAtlas Ocean (Atlantic), and held up the sky (not Earth; here both depicted as spheres).

-

An early hemispheric map of Earth (Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Geographica ac Hydrographica Tabula, Hendrik Hondius, 1630)

-

Andreas Cellarius's illustration of the Earth within the celestial sphere, from the Harmonia Macrocosmica (1660)

-

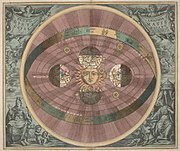

Andreas Cellarius's illustration of the Copernican system, from the Harmonia Macrocosmica (1660)

-

Memorial for the second oldest international organization the Universal Postal Union in Bern, a sculpture of Earth and the personified continents by René de Saint-Marceaux (1909),[note 1] becoming in 1967 the organization's symbol.[30]

-

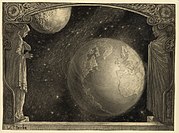

A modern depiction of Earth before any images from space (W. T. Benda, 1918).

-

Universal Studioslogo (1931)

-

United Nations flag(since 1947), with a circular polar projection of Earth at its center

Images of Earth from space

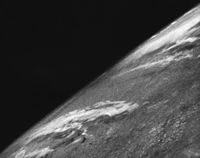

The technological developments of the latter half of the 20th century are widely considered to have altered the public's perception of the Earth. Before space flight, the popular image of Earth was of a green world. Science fiction artist Frank R. Paul provided perhaps the first image of a cloudless blue planet (with sharply defined land masses) on the back cover of the July 1940 issue of Amazing Stories, a common depiction for several decades thereafter.[31] Earth was first photographed from a satellite by

Since the 1960s, Earth has also been described as a massive "

Notable images of Earth from space

| Year | Event | Image | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1967 | 10 November 1967: NASA's first full-disc, true-color image of Earth, taken by the ATS-3 satellite. The image was used for the cover of the first edition of the Whole Earth Catalog the following year. |

| |

| 1972 | 7 December 1972: the widely used The Blue Marble was taken by the crew of Apollo 17.[39] The photograph's original orientation had south pointed up.[40] |

|

[39][41][42][43][40] |

| 1990 | 14 February 1990: the space probe took the Pale Blue Dot photograph of Earth from a record distance of about 6 billion kilometers (3.7 billion miles, 40.5 AU), as part of that day's Family Portrait series of images of the Solar System . Earth appears as a tiny dot within deep space: the blueish-white speck almost halfway up the brown band on the right.Diagram of the Family Portrait showing the planets' orbits and the relative position of Voyager 1 when the mosaic was captured. |

|

[43][44] |

| 2010 | Family Portrait (MESSENGER) |

|

[41] |

| 2013 | The Day the Earth Smiled - 2013 photograph of Saturn and Earth |

|

[43] |

Impact of images of Earth from space

Over the past two centuries a growing

See also

- Earth globe § History

- Flag of Earth

Notes

- ^ A postage stamp honoring the sculptor and the monument was issued jointly by Switzerland and France.

References

- ^ Widmer, Ted (24 December 2018). "What Did Plato Think the Earth Looked Like? - For millenniums, humans have tried to imagine the world in space. Fifty years ago, we finally saw it". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ Arnett, Bill (16 July 2006). "Earth". The Nine Planets, A Multimedia Tour of the Solar System: one star, eight planets, and more. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ Blue, Jennifer (25 June 2009). "Planetary Nomenclature FAQ". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (November 2001). "Earth". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

- ISBN 978-91-972705-0-2.

- ^ Werner, E.T.C. (1922). Myths & Legends of China. New York: George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- ^ "Bhumi, Bhūmi, Bhūmī: 41 definitions". Wisdom Library. 11 April 2009.

Earth (भूमि, bhūmi) is one of the five primary elements (pañcabhūta)

- ISBN 978-0-19-983969-8.

- ISBN 1-57607-763-2.

- . Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- ISBN 978-1-59102-064-6. Archived from the originalon 8 May 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- . Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- PMID 14527300.

- ^ Science, Evolution, and Creationism. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. 2005.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-684-17993-3.

- ^ Gould, S.J. (1997). "Nonoverlapping magisteria" (PDF). Natural History. 106 (2): 16–22. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- ISBN 9781575062471.

- ISBN 9781681778464.

- ^ "Tlaltecuhtli". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ^ Thevet, André (c. 1540). "IX". Histoyre du mechique (in French). pp. 31–34.

- ISBN 9781420511451.

- ^ "Terry Pratchett and the real science of Discworld". the Guardian. 19 May 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-415-97460-8.

- ISBN 978-0-313-32951-7.

- ^ "Themes : Dying Earth : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "Themes : Ruined Earth : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "Themes : Climate Change : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey B. "The Myth of the Flat Earth". American Scientific Affiliation. Retrieved 14 March 2007.; but see also Cosmas Indicopleustes

- ^ "The Postal History of ICAO". applications.icao.int. 10 July 1964. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^

ISBN 978-1-57544-069-9.

- ^ Staff (October 1998). "Explorers: Searching the Universe Forty Years Later" (PDF). NASA/Goddard. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2007.

- ^ An Anthem for the Earth Kathmandu Post, 25 May 2013

- ^ Staff. "Pale Blue Dot". SETI@home. Archived from the original on 17 August 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2006.

- ^ Kaufman, Mark (22 April 2023). "The farthest-away pictures of Earth ever taken - Our precious planet seen from deep space". Mashable. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-525-47433-3. Archived from the originalon 28 October 2004. Retrieved 21 April 2007.

- ISBN 978-0-19-286030-9.

- ^ "Cupola Observational Module". Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Milestones in Space Photography". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020.

- ^ a b Reinert, Al (12 April 2011). "The Blue Marble Shot: Our First Complete Photograph of Earth". The Atlantic. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ a b "Viewing The Earth From Space Celebrates 70 Years". Forbes. 22 August 2016. Archived from the original on 23 August 2016.

- ^ "Fifty Years Ago, This Photo Captured the First View of Earth From the Moon". 23 August 2016. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016.

- ^ a b c "60 Years Ago We Saw Earth From Space for the First Time — Here's How We See It Now". 22 August 2019. Archived from the original on 23 August 2019.

- ^ "Our home world from afar". 22 April 2020. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-521-45759-0.

- ISBN 978-0-8223-1569-8.

- ISBN 978-0-312-21669-6.

- .

- ^ Jaffe, A.; Adam, B.; Peterson, S.; Portney, P.; Stavins, R. (March 1995). "Environmental Regulation and the Competitiveness of U.S. Manufacturing: What Does the Evidence Tell Us?". Journal of Economic Literature. 33 (1): 132–163. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-471-01289-4.

![Memorial for the second oldest international organization the Universal Postal Union in Bern, a sculpture of Earth and the personified continents by René de Saint-Marceaux (1909),[note 1] becoming in 1967 the organization's symbol.[30]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1a/Memorial_for_the_Union_Postale_Universelle_in_Bern.jpg/180px-Memorial_for_the_Union_Postale_Universelle_in_Bern.jpg)