Gastritis

| Gastritis | |

|---|---|

| Frequency | ~50% of people[4] |

| Deaths | 50,000 (2015)[5] |

Gastritis is

Common causes include infection with

Prevention is by avoiding things that cause the disease.

Gastritis is believed to affect about half of people worldwide.

Signs and symptoms

Many people with gastritis experience no symptoms at all. However,

Other signs and symptoms may include the following:

- Nausea

- Vomiting (may be clear, green or yellow, blood-streaked or completely bloody depending on the severity of the stomach inflammation)

- Belching(does not usually relieve stomach pain if present)

- Bloating

- Early satiety[13]

- Loss of appetite

- Unexplained weight loss

Causes

There are two categories of gastritis depending on the cause of the disease. There is erosive gastritis, for which the common causes are stress, alcohol, some drugs, such as aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and Crohn's disease. And, there is non-erosive gastritis, for which the most common cause is a Helicobacter pylori infection. [15][1]

Helicobacter pylori

Critical illness

Gastritis may also develop after major surgery or traumatic injury ("Cushing ulcer"), burns ("Curling ulcer"), or severe infections. Gastritis may also occur in those who have had weight loss surgery resulting in the banding or reconstruction of the digestive tract.[citation needed]

Diet

Evidence does not support a role for specific foods, including spicy foods and coffee, in the development of

Pathophysiology

Acute

Acute erosive gastritis typically involves discrete foci of surface necrosis due to damage to mucosal defenses.

Also, alcohol consumption does not cause chronic gastritis. It does, however, erode the mucosal lining of the stomach; low doses of alcohol stimulate hydrochloric acid secretion. High doses of alcohol do not stimulate secretion of acid.[25]

Chronic

Chronic gastritis refers to a wide range of problems of the gastric tissues.

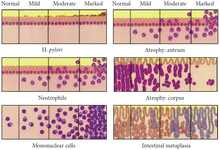

Metaplasia

Mucous gland metaplasia, the reversible replacement of differentiated cells, occurs in the setting of severe damage of the gastric glands, which then waste away (atrophic gastritis) and are progressively replaced by mucous glands. Gastric ulcers may develop; it is unclear if they are the causes or the consequences. Intestinal metaplasia typically begins in response to chronic mucosal injury in the antrum and may extend to the body. Gastric mucosa cells change to resemble intestinal mucosa and may even assume absorptive characteristics. Intestinal metaplasia is classified histologically as complete or incomplete. With complete metaplasia, gastric mucosa is completely transformed into small-bowel mucosa, both histologically and functionally, with the ability to absorb nutrients and secrete peptides. In incomplete metaplasia, the epithelium assumes a histologic appearance closer to that of the large intestine and frequently exhibits dysplasia.[20]

Diagnosis

Often, a diagnosis can be made based on patients' description of their symptoms. Other methods which may be used to verify gastritis include:

- Blood tests:

- Blood cell count

- Presence of H. pylori

- Liver, kidney, gallbladder, or pancreas functions

- Urinalysis

- Stool sample, to look for blood in the stool

- X-rays

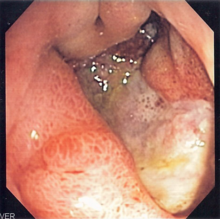

- Endoscopy, to check for stomach lining inflammation and mucous erosion

- Stomach biopsy, to test for gastritis and other conditions[27]

The OLGA staging frame of chronic gastritis on histopathology. Atrophy is scored as the percentage of atrophic glands and scored on a four-tiered scale. No atrophy (0%) = score 0; mild atrophy (1–30%) = score 1; moderate atrophy (31–60%) = score 2; severe atrophy (>60%) = score 3. These scores (0–3) are used in the OLGA staging assessment in each 10 compartment:[28]

| Corpus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No atrophy (score 0) |

Mild atrophy (score 1) |

Moderate atrophy (score 2) |

Severe atrophy (score 3) | ||

| Antrum (including incisura angularis) | |||||

| No atrophy (score 0) | Stage 0 | Stage I | Stage II | Stage II | |

| Mild atrophy (score 1) | Stage I | Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | |

| Moderate atrophy (score 2) | Stage II | Stage II | Stage III | Stage IV | |

| Severe atrophy (score 3) | Stage III | Stage III | Stage IV | Stage IV | |

Treatment

Cytoprotective agents are designed to help protect the tissues that line the stomach and small intestine.

Several regimens are used to treat H. pylori infection. Most use a combination of two

History

In 1,000 A.D,

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Gastritis". The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). November 27, 2013. Archived from the original on 6 March 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4511-6097-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-04-02.

- ^ PMID 25439069.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-08373-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-03-05.

- ^ PMID 27733281. (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators).

- ^ PMID 35944925.

- ^ a b "ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-19-937333-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-03-05.

- ISBN 978-1-4557-3394-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-08-15.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-958582-3. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-08.

- PMID 26063472. (Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators).

- PMID 21944414.

- ^ a b "Gastritis Symptoms". eMedicineHealth. 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-12-06. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ^ "Gastritis". National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. December 2004. Archived from the original on 2008-10-11. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- ^ Vakil N (June 2021). "Gastritis - Digestive Disorders". MSD Manual Consumer Version. Merck & Co. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- PMID 18396114.

- (PDF) from the original on 2012-11-05.

- ISBN 978-1-60547-968-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-04-02.

- ^ "Gastritis: Things you can do to ease gastritis". National Health Service. 2019-05-20. Retrieved 2021-08-29.

- ^ a b c Vakil N (January 2007). "Gastritis". Merck Manual - Professional Version. Merck & Co. Archived from the original on 25 January 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- PMID 18812633.[permanent dead link]

- PMID 2512924.

- S2CID 46147389.

- ^ a b Siegelbaum J (23 August 2019). "GI Health Resources > Gastritis". Jackson Siegelbaum Gastroenterology. Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- S2CID 23245888.

- ^ Mayo Clinic Staff (April 13, 2007). "Gastritis". MayoClinic. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ^ "Exams and Tests". eMedicinHealth. 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-12-11. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- license.

- ^ .

- S2CID 29732662.

- PMID 25955624.

- ^ "Gastritis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ISBN 978-953-51-0907-5. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

Further reading

- Vakil N (June 2021). "Gastritis - Digestive Disorders". MSD Manual Consumer Version. Merck & Co. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2022.