Gastroenteritis

| Gastroenteritis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Gastro, stomach bug, stomach virus, stomach flu, gastric flu, gastrointestinitis |

intravenous fluids[2] | |

| Frequency | 2.4 billion (2015)[6] |

| Deaths | 1.3 million (2015)[7] |

Gastroenteritis, also known as infectious diarrhea or simply as gastro, is an

Gastroenteritis is usually caused by

For young children in impoverished countries, prevention includes

In 2015, there were two billion cases of gastroenteritis, resulting in 1.3 million deaths globally.

Signs and symptoms

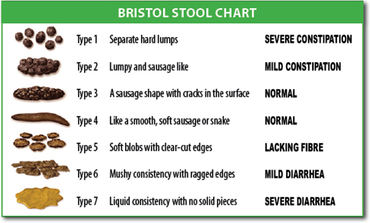

Gastroenteritis usually involves both diarrhea and vomiting.[18] Sometimes, only one or the other is present.[1] This may be accompanied by abdominal cramps.[1] Signs and symptoms usually begin 12–72 hours after contracting the infectious agent.[15] If due to a virus, the condition usually resolves within one week.[18] Some viral infections also involve fever, fatigue, headache and muscle pain.[18] If the stool is bloody, the cause is less likely to be viral[18] and more likely to be bacterial.[19] Some bacterial infections cause severe abdominal pain and may persist for several weeks.[19]

Children infected with rotavirus usually make a full recovery within three to eight days.

Cause

Viral

Norovirus is the leading cause of gastroenteritis among adults in America accounting for about 90% of viral gastroenteritis outbreaks.

Bacterial

In some countries, Campylobacter jejuni is the primary cause of bacterial gastroenteritis, with half of these cases associated with exposure to poultry.[19] In children, bacteria are the cause in about 15% of cases, with the most common types being Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter species.[13] If food becomes contaminated with bacteria and remains at room temperature for a period of several hours, the bacteria multiply and increase the risk of infection in those who consume the food.[17] Some foods commonly associated with illness include raw or undercooked meat, poultry, seafood, and eggs; raw sprouts; unpasteurized milk and soft cheeses; and fruit and vegetable juices.[30] In the developing world, especially sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, cholera is a common cause of gastroenteritis. This infection is usually transmitted by contaminated water or food.[31]

Toxigenic

Parasitic

A number of

Transmission

Transmission may occur from drinking contaminated water or when people share personal objects.

Non-infectious

There are a number of non-infectious causes of inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract.

In the United States, rates of emergency department use for noninfectious gastroenteritis dropped 30% from 2006 until 2011. Of the twenty most common conditions seen in the emergency department, rates of noninfectious gastroenteritis had the largest decrease in visits in that time period.[39]

Pathophysiology

Gastroenteritis is defined as

Diagnosis

Gastroenteritis is typically diagnosed clinically, based on a person's signs and symptoms.[18] Determining the exact cause is usually not needed as it does not alter the management of the condition.[15]

However,

Dehydration

A determination of whether or not the person has

Differential diagnosis

Other potential causes of signs and symptoms that mimic those seen in gastroenteritis that need to be ruled out include

Appendicitis may present with vomiting, abdominal pain, and a small amount of diarrhea in up to 33% of cases.[1] This is in contrast to the large amount of diarrhea that is typical of gastroenteritis.[1] Infections of the lungs or urinary tract in children may also cause vomiting or diarrhea.[1] Classical diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) presents with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, but without diarrhea.[1] One study found that 17% of children with DKA were initially diagnosed as having gastroenteritis.[1]

Prevention

Water, sanitation, hygiene

A supply of easily accessible uncontaminated water and good sanitation practices are important for reducing rates of infection and clinically significant gastroenteritis.[17] Personal hygiene measures (such as hand washing with soap) have been found to decrease rates of gastroenteritis in both the developing and developed world by as much as 30%.[23] Alcohol-based gels may also be effective.[23] Food or drink that is thought to be contaminated should be avoided.[44] Breastfeeding is important, especially in places with poor hygiene, as is improvement of hygiene generally.[15] Breast milk reduces both the frequency of infections and their duration.[1]

Vaccination

Due to both its effectiveness and safety, in 2009 the World Health Organization recommended that the rotavirus vaccine be offered to all children globally.[25][45] Two commercial rotavirus vaccines exist and several more are in development.[45] In Africa and Asia these vaccines reduced severe disease among infants[45] and countries that have put in place national immunization programs have seen a decline in the rates and severity of disease.[46][47] This vaccine may also prevent illness in non-vaccinated children by reducing the number of circulating infections.[48] Since 2000, the implementation of a rotavirus vaccination program in the United States has substantially decreased the number of cases of diarrhea by as much as 80 percent.[49][50][51] The first dose of vaccine should be given to infants between 6 and 15 weeks of age.[25] The oral cholera vaccine has been found to be 50–60% effective over two years.[52]

There are a number of vaccines against gastroenteritis in development. For example, vaccines against Shigella and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), which are two of the leading bacterial causes of gastroenteritis worldwide.[53][54]

Management

Gastroenteritis is usually an acute and self-limiting disease that does not require medication.

Rehydration

The primary treatment of gastroenteritis in both children and adults is

Dietary

It is recommended that breast-fed infants continue to be nursed in the usual fashion, and that formula-fed infants continue their formula immediately after rehydration with ORT.

A Cochrane Review from 2020 concludes that

Antiemetics

Antiemetic medications may be helpful for treating vomiting in children. Ondansetron has some utility, with a single dose being associated with less need for intravenous fluids, fewer hospitalizations, and decreased vomiting.[55][66][67][68] Metoclopramide might also be helpful.[68] However, the use of ondansetron might possibly be linked to an increased rate of return to hospital in children.[69] The intravenous preparation of ondansetron may be given orally if clinical judgment warrants.[70] Dimenhydrinate, while reducing vomiting, does not appear to have a significant clinical benefit.[1]

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are not usually used for gastroenteritis, although they are sometimes recommended if symptoms are particularly severe

Antimotility agents

Antimotility medication has a theoretical risk of causing complications, and although clinical experience has shown this to be unlikely,

Epidemiology

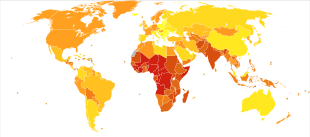

| no data ≤500 500–1000 1000–1500 1500–2000 2000–2500 2500–3000 | 3000–3500 3500–4000 4000–4500 4500–5000 5000–6000 ≥6000 |

It is estimated that there were two billion cases of gastroenteritis that resulted in 1.3 million deaths globally in 2015.

In 1980, gastroenteritis from all causes caused 4.6 million deaths in children, with the majority occurring in the developing world.[73] Death rates were reduced significantly (to approximately 1.5 million deaths annually) by 2000, largely due to the introduction and widespread use of oral rehydration therapy.[80] In the US, infections causing gastroenteritis are the second most common infection (after the common cold), and they result in between 200 and 375 million cases of acute diarrhea[17][18] and approximately ten thousand deaths annually,[17] with 150 to 300 of these deaths in children less than five years of age.[1]

Society and culture

Gastroenteritis is associated with many colloquial names, including "

Gastroenteritis is the main reason for 3.7 million visits to physicians a year in the United States[1] and 3 million visits in France.[81] In the United States gastroenteritis as a whole is believed to result in costs of US$23 billion per year,[82] with rotavirus alone resulting in estimated costs of US$1 billion a year.[1]

Terminology

The first usage of "gastroenteritis" was in 1825.[83] Before this time it was commonly known as typhoid fever or "cholera morbus", among others, or less specifically as "griping of the guts", "surfeit", "flux", "colic", "bowel complaint", or any one of a number of other archaic names for acute diarrhea.[84] Cholera morbus is a historical term that was used to refer to gastroenteritis rather than specifically cholera.[85]

Other animals

Many of the same agents cause gastroenteritis in cats and dogs as in humans. The most common organisms are Campylobacter, Clostridium difficile, Clostridium perfringens, and Salmonella.[86] A large number of toxic plants may also cause symptoms.[87]

Some agents are more specific to a certain species.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Singh A (July 2010). "Pediatric Emergency Medicine Practice Acute Gastroenteritis — An Update". Pediatric Emergency Medicine Practice. 7 (7).

- ^ PMID 24194646.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-08430-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-08.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-5734-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-08.

- ISBN 978-1-4051-0357-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-08.

- ^ PMID 27733282.

- ^ PMID 27733281.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-107-03891-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-08.

- ISBN 978-1-4496-7333-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-08.

- ^ PMID 22030330.

- PMID 21695033.

- S2CID 24103030.

- ^ PMID 15861741.

- PMID 25769427.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84593-504-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-10-26.

- ^ PMID 23582727.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-443-06839-3.

- ^ PMID 21210762.

- ^ PMID 17846438.

- ^ S2CID 44379279.

- ^ "Toolkit". DefeatDD. Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Management of acute diarrhoea and vomiting due to gastoenteritis in children under 5". National Institute of Clinical Excellence. April 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-08-02. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-148480-0.

- ^ PMID 17204802.

- ^ S2CID 5083478.

- ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5.

- PMID 21288818.

- PMID 24981041.

- PMID 21210762. Retrieved 2020-12-22.

- PMID 20500787.

- ^ S2CID 6907842.

- S2CID 23015631.

- S2CID 2023416.

- ^ a b c "Persistent Travelers' Diarrhea". United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 10 July 2015. Archived from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

Although most cases of travelers' diarrhea are acute and self-limited, a certain percentage of travelers will develop persistent (>14 days) gastrointestinal symptoms ... Parasites as a group are the pathogens most likely to be isolated from patients with persistent diarrhea

- ^ S2CID 12326803.

- ^ PMID 20701575.

- PMID 19962025.

- PMID 17482025.

- ^ Skiner HG, Blanchard J, Elixhauser A (September 2014). "Trends in Emergency Department Visits, 2006–2011". HCUP Statistical Brief #179. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Archived from the original on 2014-12-24.

- PMID 29053792.

- PMID 15187057.

- S2CID 29662891.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-262922-7. Archived from the originalon 2012-03-21.

- ^ "Viral Gastroenteritis". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. February 2011. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- PMID 20622508. Archived from the originalon 17 February 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- S2CID 1893099.

- from the original on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- from the original on 2009-10-31.

- S2CID 20940659.

- PMID 21412922.

- ^ World Health Organization. "Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC)". Diarrhoeal Diseases. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ World Health Organization. "Shigellosis". Diarrhoeal Diseases. Archived from the original on 15 December 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ PMID 21901699.

- S2CID 46971321.

- ^ "BestBets: Fluid Treatment of Gastroenteritis in Adults". Archived from the original on 2009-02-12.

- PMID 19817339.

- PMID 27959472.

- S2CID 20509810.

- ^ from the original on 2014-10-28.

- PMID 33295643.

- PMID 22570464.

- ^ Mackway-Jones K (June 2007). "Does yogurt decrease acute diarrhoeal symptoms in children with acute gastroenteritis?". BestBets. Archived from the original on 2009-02-12.

- PMID 21359029.

- PMID 18762604.

- PMID 17279195.

- ^ PMID 21901699.

- PMID 20031265.

- ^ "Ondansetron". Lexi-Comp. May 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-06-06.

- PMID 20348130.

- PMID 19962025.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-443-06643-6. Archived from the originalon 2013-10-18. Retrieved 2006-04-22.

- PMID 20687081.

- PMID 21975746.

- PMID 30624763.

- ISBN 978-0-07-140235-4. Archived from the originalon 2012-08-04. Retrieved 2006-04-22.

- ISBN 978-0-7216-8973-9.

- (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- PMID 11100619.

- PMID 22046706.

- ISBN 978-1-58829-520-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-28.

- ^ "Gastroenteritis". Oxford English Dictionary 2011. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ^ Rudy's List of Archaic Medical Terms Archived 2007-07-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 978-0-226-72676-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-09.

- PMID 21486637.

- ISBN 978-0-12-370469-6. Archived from the original on 2016-05-07.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISBN 978-0-12-375158-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-25.

- ISBN 978-0-12-263951-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-28.

- ISBN 978-0-8138-2267-9. Archivedfrom the original on 28 November 2015.

Notes

- Dolin R, Mandell GL, Bennett JE, eds. (2010). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-443-06839-3.

External links

- Diarrhoea and Vomiting Caused by Gastroenteritis: Diagnosis, Assessment and Management in Children Younger than 5 Years – NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 84.

- "Gastroenteritis". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.