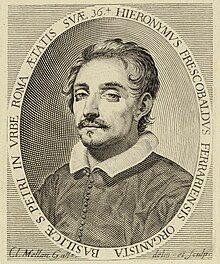

Girolamo Frescobaldi

Girolamo Alessandro Frescobaldi (Italian: [dʒiˈrɔːlamo freskoˈbaldi]; also Gerolamo, Girolimo, and Geronimo Alissandro; September 1583[n 1] – 1 March 1643) was an Italian composer and virtuoso keyboard player.[1] Born in the Duchy of Ferrara, he was one of the most important composers of keyboard music in the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods. A child prodigy, Frescobaldi studied under Luzzasco Luzzaschi in Ferrara, but was influenced by many composers, including Ascanio Mayone, Giovanni Maria Trabaci, and Claudio Merulo. Girolamo Frescobaldi was appointed organist of St. Peter's Basilica, a focal point of power for the Cappella Giulia (a musical organisation), from 21 July 1608 until 1628 and again from 1634 until his death.[2]

Frescobaldi's printed collections contain some of the most influential music of the 17th century. His work influenced Johann Jakob Froberger, Johann Sebastian Bach, Henry Purcell, and other major composers. Pieces from his celebrated collection of liturgical organ music, Fiori musicali (1635), were used as models of strict counterpoint as late as the 19th century.

Life

Frescobaldi was born in

In his early twenties, Frescobaldi left his native Ferrara for Rome. Reports place Frescobaldi in that city as early as 1604, but his presence can only be confirmed by 1607. He was the church organist at

Between 1610 and 1613, Frescobaldi began to work for Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini. He remained in his service until after the death of Cardinal Aldobrandini in February 1621.[11] On 18 February 1613, he married Orsola Travaglini, known as Orsola del Pino.[12] The couple had five children: Francesco (an illegitimate child born on 29 May 1612), Maddalena (an illegitimate child born on 22 July 1613), Domenico (8 November 1614, poet and art collector), Stefano (1616/7), and Caterina (September 1619).[13]

In October 1614, Frescobaldi was approached by an agent of the Duke of

St. Peter's Basilica gave Frescobaldi permission to leave Rome on 22 November 1628. Girolamo moved to

Music

Frescobaldi was, after Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck, the first of the great composers of the ancient Franco-Netherlandish-Italian tradition who chose to focus his creative energy on instrumental composition.[19] Frescobaldi brought a wide range of emotion to the relatively unplumbed depths of instrumental music.[20] Keyboard music occupies the most important position in Frescobaldi's extant oeuvre.[21] He published eight collections of it during his lifetime, several were reprinted under his supervision, and more pieces were either published posthumously or transmitted in manuscripts.[22] His collection of instrumental ensemble canzonas, Il Primo Libro delle Canzoni, was published in two editions in Rome in 1628, and substantially revised in the Venice edition of 1634. Of the forty pieces in the collection, ten were replaced and all were revised to various degrees, sixteen of them radically so. This extensive editing attests to Frescobaldi's ongoing interest in the utmost perfection of his pieces and collections.[23]

Frescobaldi's compositional canon began with his 1615 publications.[24] One of the publications issued in 1615 was Ricercari, et canzone. This work returned to the old-fashioned, pure style of ricercar. Fast note values and triple meter were not allowed to detract from the purity of style.[25] A second publication of 1615 was the Toccate e partite which established expressive keyboard style. Frescobaldi did not obey the conventional rules for composing, ensuring no two works have a similar structure.[25] From 1615 to 1628, Frescobaldi's publications connect him with the Congregazione exactly when the group's activities determined the Roman musical trends.[26]

Frescobaldi's next stream of compositions expanded their artistic range beyond the keyboard music that he had focused on previously.

In 1635, Frescobaldi published

Aside from Fiori musicali, Frescobaldi's two books of toccatas and partitas (1615 and 1627) are his most important collections.[29] His toccatas could be used in masses and liturgical occasions. These toccatas served as preludes to larger pieces, or were pieces of substantial length standing alone.[30] The Secondo libro, written in 1627, stretches the conception of the genres included in the first book of toccatas. More variety is introduced with different rhythmic techniques and four organ pieces.[21] Both books open with a set of twelve toccatas written in a flamboyant improvisatory style and alternating fast-note runs or passaggi with more intimate and meditative parts, called affetti, plus short bursts of contrapuntal imitation.

Although Frescobaldi was influenced by numerous earlier composers such as the Neapolitans

Frescobaldi also made substantial contributions to the art of variation; he may have been one of the first composers to introduce the juxtaposition of the ciaccona and passacaglia into the music repertory, as well as the first to compose a set of variations on an original theme (all earlier examples are variations on folk or popular melodies).[21] Frescobaldi showed an increasing interest in composing intricate works out of unrelated individual pieces during his last years of composing.[23] The last work Frescobaldi composed, Cento partite sopra passacagli, was his most impressive creative work. The Cento displays Frescobaldi's new interest in combining different pieces that were first written independently.[23]

The composer's other works include collections of

Legacy

Contemporary critics acknowledged Frescobaldi as one of the greatest trendsetters of keyboard music of their time. Even critics who did not approve of Frescobaldi's vocal works agreed that he was a genius both playing and composing for the keyboard.[33] Frescobaldi's music did not lose direct influence until the 1660s, and his works held influence over the development of keyboard music over a century after his death. Bernardo Pasquini promoted Girolamo Frescobaldi to the rank of pedagogical authority.[34]

Frescobaldi's pupils included numerous Italian composers, but the most important was a German, Johann Jakob Froberger, who studied with him in 1637–41.[35] Froberger's works were influenced not only by Frescobaldi but also by Michelangelo Rossi; he became one of the most influential composers of the 17th century, and, similarly to Frescobaldi, his works were still studied in the 18th century. Frescobaldi's work was known to, and influenced, numerous major composers outside Italy, including Henry Purcell, Johann Pachelbel, and Johann Sebastian Bach.

Bach is known to have owned a number of Frescobaldi's works, including a manuscript copy of Frescobaldi's Fiori musicali (Venice, 1635), which he signed and dated 1714 and performed in Weimar the same year. Frescobaldi's influence on Bach is most evident in his early choral preludes for organ. Finally, Frescobaldi's toccatas and canzonas, with their sudden changes and contrasting sections, may have inspired the celebrated stylus fantasticus of the North German organ school.

The WYSIWYG editor for LilyPond music files is called Frescobaldi to honour the composer.[36]

References

Notes

- ^ Sources are in dispute about the interpretation of Frescobaldi's birth and baptism records; 9 September has long appeared in references as his baptism date (which would mean he was born no later than that date, and probably a day or two earlier), but more recent research suggests a birth date of 13 September or 15 September may be more accurate.

Citations

- ^ Hammond & Silbiger 2001.

- ^ Hammond 1983, pp. 47, 54, 79. 81.

- ^ a b Hammond 1983, p. 3.

- ^ Hammond 1983, pp. 7, 10.

- ^ Hammond 1983, pp. 16, 20.

- ^ Hammond 1983, p. 28.

- ^ Hammond 1983, p. 31.

- ^ Hammond 1983, pp. 31, 33.

- ^ Hammond 1983, pp. 33, 47.

- ^ Hammond 1983, pp. 30, 40, 41, 43.

- ^ Hammond 1983, pp. 45.

- ^ Hammond 1983, p. 44.

- ^ Hammond 1983, pp. 44, 58.

- ^ Hammond 1983, pp. 47, 54.

- ^ Hammond 1983, pp. 54, 66.

- ^ Hammond 1983, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Hammond 1983, p. 78.

- ^ Hammond 1983, pp. 83, 86–87.

- ^ Silbiger 1987, p. 8.

- ^ Silbiger 1987, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Silbiger 1987, p. 5.

- ^ Hammond 1983, pp. 274–289.

- ^ a b c Silbiger 1987, p. 7.

- ^ a b Silbiger 1987, p. 4.

- ^ a b Silbiger 1987, p. 3.

- ^ Hammond 1983, p. 64.

- ^ a b c d e Silbiger 1987, p. 6.

- ^ Bukofzer 1947, p. 48.

- ^ Hammond 1983, p. 66.

- ^ Bukofzer 1947, p. 47.

- ^ Bukofzer 1947, pp. 48, 50.

- ^ Artz 1962, p. 143.

- ^ Hammond 1983, p. 93.

- ^ Hammond 1983, p. 93–95.

- ^ Hammond & Silbiger 2001, "6. Pupils.".

- ^ "Frescobaldi: Edit LilyPond sheet music with ease!". frescobaldi.org. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

Sources

- Artz, Frederick B (1962). From the Renaissance to Romanticism: Trends in Style in Art, Literature, and Music, 1300–1830. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 143–205.

- W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.pp. 43–54.

- Hammond, Frederick (1983). Girolamo Frescobaldi. Cambridge: ISBN 0-674-35438-9.

- Hammond, Frederick; Silbiger, Alexander (2001). "Frescobaldi, Girolamo [Gerolamo, Girolimo] Alessandro". ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription or UK public library membershiprequired)

- Silbiger, Alexander (1987). "An Introduction to Frescobaldi". In Silbiger, Alexander (ed.). Frescobaldi Studies. Durham: Duke University. pp. 1–10.

Further reading

- ISBN 0-253-21141-7. Originally published as Geschichte der Orgel- und Klaviermusik bis 1700 by Bärenreiter-Verlag, Kassel.

- Morgante, Domenico (1986). "Girolamo Frescobaldi". Dizionario Enciclopedico Universale della Musica e dei Musicisti (DEUMM) (in Italian). Vol. III. Torino: UTET.

External links

- Free scores by Girolamo Frescobaldi at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by Girolamo Frescobaldi in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Kunst der Fuge: Girolamo Frescobaldi – MIDI files

- FTCO Frescobaldi Thematic Catalogue Online; An online thematic catalogue of all compositions attributed to Girolamo Frescobaldi and a database of the early sources, modern and facsimile editions, and literature. JSCM Instrumenta, Volume 6, Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

- Frescobaldi dedicated website