Monkeypox virus

| Orthopoxvirus monkeypox | |

|---|---|

| |

| Colorized transmission electron micrograph of monkeypox virus particles (teal) found within an infected cell (brown), cultured in the laboratory. | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Varidnaviria |

| Kingdom: | Bamfordvirae |

| Phylum: | Nucleocytoviricota |

| Class: | Pokkesviricetes |

| Order: | Chitovirales |

| Family: | Poxviridae |

| Genus: | Orthopoxvirus |

| Species: | Orthopoxvirus monkeypox

|

| Clades | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

MPV, MPXV, hMPXV | |

The monkeypox virus (MPV, MPXV, or hMPXV) viruses. MPV is oval, with a lipoprotein outer membrane. Its genome is approximately 190 kb. Smallpox and monkeypox viruses are both orthopoxviruses, and the smallpox vaccine is effective against mpox if given within 3–5 years before the disease is contracted.[4] Symptoms of mpox in humans include a rash that forms blisters and then crusts over, fever, and swollen lymph nodes.[5] The virus is transmissible between animals and humans by direct contact to the lesions or via bodily fluids.[6]

The virus was given the name monkeypox virus after being isolated from monkeys, but most of the carriers of this virus are smaller mammals.[5]

The virus is endemic in Central Africa, where infections in humans are relatively frequent.[5][7] Though there are many natural hosts for the monkeypox virus, the exact reservoirs and how the virus is circulated in nature needs to be studied further.[8]

Virology

Classification

The monkeypox virus is a zoonotic virus belonging to the genus Orthopoxvirus, which itself is a member of the family Poxviridae (also known as the poxvirus family).[9] Of note, the Orthopoxvirus genus includes the variola virus that prior to eradication via the advent of the smallpox vaccine, was the cause of the infectious human disease known as smallpox.[10] Members of the poxvirus family, include the monkeypox virus itself have been listed by the WHO as diseases with epidemic or pandemic potential.[11] The monkeypox virus is listed as being a potentially high or severe threat pathogen in both the European Union (EU) and the United States of America.[11][12][13]

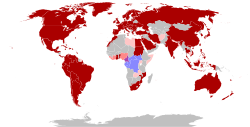

There are two subtypes or clades, clade I historically associated with the Congo Basin and clade II historically associated with West Africa. A global outbreak during 2022–2023 was caused by clade II.[5]

MPV is 96.3% identical to the variola virus in regards to its coding region, but it does differ in parts of the genome which encode for virulence and host range.[14] Through phylogenetic analysis, it was found that MPV is not a direct descendant of the variola virus.[14]

Structure and genome

The monkeypox virus, like other poxviruses, is oval, with a lipoprotein outer membrane. The outer membrane protects the enzymes, DNA, and transcription factors of the virus.[15] Typical DNA viruses replicate and express their genome in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells, relying heavily on the host cell's machinery. However, monkeypox viruses rely mostly on proteins encoded in their genome that allow them to replicate in the cytoplasm.[16]

The genome of the monkeypox virus comprises 200

Monkeypox virus is relatively large, compared to other viruses. This makes it harder for the virus to breach the host defences, such as crossing gap junctions. Furthermore, the large size makes it harder for the virus to replicate quickly and evade immune response.[16] To evade host immune systems, and buy more time for replication, monkeypox and other orthopox viruses have evolved mechanisms to evade host immune cells.[20]

Replication and life cycle

This section may be too technical for most readers to understand. (June 2023) |

As an Orthopoxvirus, MPV replication occurs entirely in the cell cytoplasm within 'factories' – created from the host rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER) – where viral mRNA transcription and translation also take place.[21][22] The factories are also where DNA replication, gene expression, and assembly of mature virions (MV) are located.[23]

MPV virions (MVs) are able to bind to the cell surface with the help of viral proteins.[24] Virus entry into the host cell plasma membrane is dependent on a neutral pH, otherwise entry occurs via a low-pH dependent endocytic route.[24] The MV of the monkeypox virus has an Entry Fusion Complex (EFC), allowing it to enter the host cell after attachment.[24]

The viral mRNA is translated into structural virion protein by the host ribosomes.[21] Gene expression begins when MPV releases viral proteins and enzymatic factors that disable the cell.[25] Mature virions are infectious. However, they will stay inside the cell until they are transported from the factories to the Golgi/endosomal compartment.[23] Protein synthesis allows for the ER membrane of the factory to dismantle, while small lipid-bilayer membranes will appear to encapsulate the genomes of new virions, now extracellular viruses (EVs).[25][21][23] The VPS52 and VPS54 genes of the GARP complex, which is important for transport, are necessary for wrapping the virus, and formation of EVs.[23] DNA concatemers process the genomes, which appear in new virions, along with other enzymes, and genetic information needed for the replication cycle to occur.[25] EVs are necessary for the spread of the virus from cell-to-cell and its long-distance spread.[23]

Transmission

Animal to human

Human to human

Monkeypox virus can be transmitted from one person to another through contact with infectious lesion material or fluid on the skin, in the mouth or on the genitals; this includes touching, close contact and during sex. It may also spread by means of respiratory droplets from talking, coughing or sneezing.[5][28] During the 2022-2023 outbreak, transmission between people was almost exclusively via sexual contact.[29] There is a lower risk of infection from fomites (objects which can become infectious after being touched by an infected person) such as clothing or bedding, but precautions should be taken.[5]

The virus then enters the body through broken skin, or mucosal surfaces such as the mouth, respiratory tract, or genitals.[30][31]

Human to animal

There are two recorded instances of human to animal transmission. Both occurred during the 2022–2023 global mpox outbreak. In both cases, the owners of a pet dog first became infected with mpox and transmitted the infection to the pet.[32][31]

Mpox disease

Human

Animal

Prevention

Vaccine

Historically, smallpox vaccine had been reported to reduce the risk of mpox among previously vaccinated persons in Africa. The decrease in immunity to poxviruses in exposed populations is a factor in the increasing prevalence of human mpox. It is attributed to waning cross-protective immunity among those vaccinated before 1980, when mass smallpox vaccinations were discontinued, and to the gradually increasing proportion of unvaccinated individuals.[38]

As of August 2024, there are four vaccines in use to prevent mpox. All were originally developed to combat smallpox.[39]

- MVA-BN (marketed as Jynneos, Imvamune or Imvanex) manufactured by Bavarian Nordic. Licensed for use against mpox in Europe, United States and Canada.[40]

- LC16 from KMB Biologics (Japan) – licensed for use in Japan.[41]

- OrthopoxVac, licensed for use in Russia and manufactured by the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology VECTOR in Russia[42]

- ACAM2000, manufactured by Emergent BioSolutions. Approved for use against mpox in the United States as of August 2024.[43][44]

The MVA-BN and ACAM 2000 vaccines both contain vaccinia virus. Vaccinia is a less virulent orthopoxvirus than either monkeypox virus or variola virus (the causative agent of smallpox), and owing to a high level of protein identity among orthopoxviruses, the 2 vaccinia virus vaccines elicit antibodies that provide cross-protection against other orthopoxviruses such as monkeypox virus. Because the vaccinia virus in the MVA-BN vaccine cannot replicate, it is recommended over ACAM2000 in the United States for use by persons who are either considered at high risk of exposure to mpox, or who may have recently been exposed to it.[45]

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that persons investigating mpox outbreaks, those caring for infected individuals or animals, and those exposed by close or intimate contact with infected individuals or animals should receive a vaccination.[46] The CDC and the EMA recommend the use of a 2-dose MVA-BN vaccination series for adults who are considered at risk for becoming infected with mpox through sexual activity.[45][47]

Other measures

The CDC has made detailed recommendations in addition to the standard precautions for infection control. These include that healthcare providers don a gown, mask, goggles, and a disposable filtering respirator (such as an N95), and that an infected person should be isolated a private room to keep others from possible contact.[48]

Those living in countries where mpox is endemic should avoid contact with sick mammals such as rodents, marsupials, non-human primates (dead or alive) that could harbour Orthopoxvirus monkeypox and should refrain from eating or handling wild game (bush meat).[49][50]

During the 2022–2023 outbreak, several public health authorities launched public awareness campaigns in order to reduce spread of the disease.[51][52][53]Treatment

Immune system interaction

Pox viruses have mechanisms to evade the hosts' innate and adaptive immune systems. Viral proteins, expressed by infected cells, employ multiple approaches to limit immune system activity, including binding to, and preventing activation of proteins within the host's immune system, and preventing infected cells from dying to enable them to continue replicating the monkey pox virus.[60]

Variants and clades

The virus is subclassified into two clades, clade I and clade II.[5] At the protein level, the clades share 170 orthologs, and their transcriptional regulatory sequences show no significant differences.[11] Both clades have 53 common virulence genes, which contain different types of amino acid changes. 121 of the amino acid changes in the virulence genes are silent, while 61 are conservative, and 93 are non-conservative.[11]

Historically, the case fatality rate (CFR) of past outbreaks was estimated at between 1% and 10%, with clade I considered to be more severe than clade II.[61] The CFR of the 2022-2023 global outbreak (caused by clade IIb) has been very low - estimated at 0.16%, with the majority of deaths in individuals who were already immunocompromised.[62]

| Name[63] | Former names[63] | Nations[64][65] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clade I | Clade Ia | Congo Basin

Central African |

|

| Clade Ib |

| ||

| Clade II | Clade IIa | West African | |

| Clade IIb | Widespread globally - See 2022–2023 mpox outbreak § Cases per country and territory | ||

History

Monkeypox virus was first identified by

The first human infection was diagnosed 1970, in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Notes

References

- ^ "Mpox (monkeypox) outbreak 2022". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 7 January 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Taxon Details | ICTV". ictv.global. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "WHO recommends new name for monkeypox disease" (Press release). World Health Organization (WHO). 28 November 2022. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Hibbert CM (11 August 2022). "Baby boomer alert: Will your childhood smallpox vaccine protect against monkeypox?". News @ Northeastern. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "WHO Factsheet – Mpox (Monkeypox)". World Health Organization (WHO). 18 April 2023. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ "Monkeypox in the U.S." U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 18 October 2022. Archived from the original on 26 October 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- PMID 35148313.

- ^ "Mpox in Animals". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 27 April 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- PMID 36298710.

- PMID 25763864.

- ^ PMID 36165924.

- PMID 24979754.

- PMID 30234087.

- ^ PMID 11734207.

- PMID 33167496.

- ^ PMID 35928395.

- PMID 36202208.

- PMID 24457084.

- ^ "Monkeypox: What We Do and Don't Know About Recent Outbreaks". ASM.org. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- PMID 36819041.

- ^ a b c "Monkeypox: What We Do and Don't Know About Recent Outbreaks". ASM.org. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- PMID 23838441.

- ^ PMID 28331092.

- ^ PMID 27423915.

- ^ PMID 20667104.

- ^ "Monkeypox". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- PMID 35928395.

- ^ "Mpox - How It Spreads". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2 February 2023. Archived from the original on 21 May 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "Safer Sex, Social Gatherings, and Mpox". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 28 April 2023. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ^ "WHO Factsheet – Mpox (Monkeypox)". World Health Organization (WHO). 18 April 2023. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Brazil: Domestic puppy in Minas Gerais contracts monkeypox, Lived with confirmed human case". Outbreak News Today. 30 August 2022. Archived from the original on 10 June 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- PMID 35963267.

- ^ a b c "WHO Factsheet – Mpox (Monkeypox)". World Health Organization (WHO). 18 April 2023. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ "Mpox Symptoms". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 15 March 2024. Archived from the original on 2 April 2024. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- PMID 37410383.

- ^ a b "Mpox in Animals". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 4 January 2023. Archived from the original on 15 August 2024. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-8138-1014-0. Archivedfrom the original on 15 August 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- PMID 27404372.

- ^ Rigby J (14 August 2024). "Mpox vaccines likely months away even as WHO, Africa CDC discuss emergency". Reuters.

- ^ Cornall J (25 July 2022). "Bavarian Nordic gets European monkeypox approval for smallpox vaccine". Labiotech UG. Retrieved 15 August 2024.

- ^ "Mpox – Prevention". British Medical Journal. Retrieved 15 August 2024.

- ^ "The Vector center will soon commence the production of the smallpox vaccine". GxP News. 26 September 2023. Retrieved 15 August 2024.

- ^ "FDA Roundup: August 30, 2024". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 30 August 2024. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ "Emergent BioSolutions' ACAM2000, (Smallpox and Mpox (Vaccinia) Vaccine, Live) Receives U.S. FDA Approval for Mpox Indication; Public Health Mpox Outbreak Continues Across Africa & Other Regions" (Press release). Emergent Biosolutions. 29 August 2024. Retrieved 1 September 2024 – via GlobeNewswire.

- ^ PMC 12176103.

- ^ "About Mpox". Mpox. 26 September 2024. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

- ^ "Considerations on posology for the use of the vaccine Jynneos/ Imvanex (MVA-BN) against monkeypox" (PDF). European Medicines Agency (EMA). 19 August 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ "Infection Prevention and Control of Mpox in Healthcare Settings". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 31 October 2022. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ "Multi-country monkeypox outbreak in non-endemic countries: Update". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ a b c "Mpox". World Health Organization (WHO). 17 August 2024. Archived from the original on 19 August 2024. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ "CDC's Mpox Toolkit for Event Organizers". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 23 May 2023. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ "Monkeypox – Campaign details". Department of Health and Social Care – Campaign Resource Centre. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ "Mpox (Monkeypox) awareness campaign: Communications toolkit for stakeholders". Western Australia Department of Health. 10 June 2022. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ "Mpox: background information". UK Health Security Agency. 19 August 2024. Archived from the original on 20 August 2024. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ "Patient's Guide to Mpox Treatment with Tecovirimat (TPOXX)". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 28 November 2022. Archived from the original on 24 May 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ "Tecovirimat SIGA". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 28 January 2022. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "Mpox (formerly Monkeypox)". NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. 6 December 2022. Archived from the original on 23 May 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ PMID 36916727.

- ^ "Mpox (monkeypox) – Treatment algorithm". BMJ Best Practice. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- PMID 36064780.

- from the original on 31 May 2023. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ "Mpox (monkeypox) - Prognosis". BMJ Best Practice. Archived from the original on 31 May 2023. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Monkeypox: experts give virus variants new names". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 19 August 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ "Monkeypox". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- PMID 16186219.

- from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ^ Igiebor FA, Agbontaen OJ, Egharevba PA, Amengialue OO, Ehiaghe JI, Ovwero E, et al. (May 2022). "Monkeypox: Emerging and Re-Emerging Threats in Nigeria". Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences. 7 (1). Benin City, Nigeria: Faculty of Science, Benson Idahosa University: 119–132. Archived from the original on 7 June 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- PMID 12149352.

- ^ "2003 U.S. Outbreak Monkeypox". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 May 2015. Archived from the original on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ "UAE donates monkeypox vaccines to 5 African countries". gulfnews.com. 31 August 2024. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

External links

Media related to Monkeypox virus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Monkeypox virus at Wikimedia Commons- CDC Questions and Answers About Monkeypox

- CDC – Human Monkeypox – Kasai Oriental, Zaire, 1996–1997 Archived 2022-05-23 at the Wayback Machine

- CDC – Outbreak of Human Monkeypox, Democratic Republic of Congo, 1996 to 1997

- CDC Preliminary Report: Multistate Outbreak of Monkeypox in Persons Exposed to Pet Prairie Dogs

- National Library of Medicine – Monkeypox virus

- Virology.net Picturebook: Monkeypox Archived 2005-10-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Viralzone: Orthopoxvirus

- Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Poxviridae

- World Health Organization to rename the Monkeypox Virus