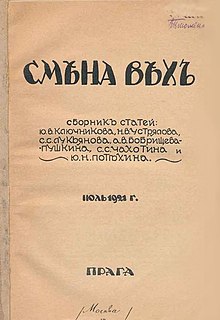

Smenovekhovtsy

The Smenovekhovtsy (Russian: Сменовеховцы, IPA: [smʲɪnəˈvʲexəftsɨ]), a political movement in the Russian émigré community, formed shortly after the publication of the magazine Smena Vekh ("Change of Signposts") in Prague in 1921.[1] This publication had taken its name from the Russian philosophical publication Vekhi ("Signposts") published in 1909. The Smena Vekh periodical told its White émigré readers:

"The Civil War is lost definitely. For a long time Russia has been travelling on its own path, not our path ... Either recognize this Russia, hated by you all, or stay without Russia, because a 'third Russia' by your recipes does not and will not exist ... The Soviet regime saved Russia - the Soviet regime is justified, regardless of how weighty the arguments against it are ... The mere fact of its enduring existence proves its popular character, and the historical belonging of its dictatorship and harshness."

Ideology

The ideas in the publication soon evolved into the Smenovekhovstvo movement, which promoted the concept of accepting the

Smenovekhovtsy supported co-operation with the Soviet government in the hope that the Soviet state would evolve back into a "bourgeois state". Such cooperation was important for the

Opposition

Conservative émigrés such as those in the

History

Representatives of the Smenovekhovtsy who settled in the Soviet Union did not survive the end of the 1930s; almost all the former leaders of the movement were arrested by the NKVD and executed at a later date.[6][7]

There were other émigré organizations which, like the Smenoveknovtsy, argued that Russian émigrés should accept the fact of the Russian revolution. These included the Young Russians (

Bibliography

- Christopher Gilley, The 'Change of Signposts' in the Ukrainian Emigration. A Contribution to the History of Sovietophilism in the 1920s, Stuttgart: ibidem, 2009.

- Hilda Hardeman, Coming to Terms with the Soviet Regime. The "Changing Signposts" Movement among Russian Émigrés in the Early 1920s, Dekalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1994.

- M.V. Nazarov, The Mission of the Russian Emigration, Moscow: Rodnik, 1994. ISBN 5-86231-172-6

- "Changing Landmarks" in Russian Berlin, 1922-1924 by Robert C. Williams in Slavic Review Vol. 27, No. 4 (Dec., 1968), pp. 581–593

See also

- Nikolay Vasilyevich Ustryalov

- National Bolshevism

References

- ^ "Lenin: Draft Decision for the Politbureau of the C.C., R.C.P.(B.) in Connection with the Genoa Conference". Marxists Internet Archive.

- ISBN 0-19-510282-7.

- S2CID 155437029.

- S2CID 155437029.

- S2CID 155437029.

- ^ "СМЕНОВЕХОВСТВО • Большая российская энциклопедия - электронная версия". bigenc.ru. Retrieved 2022-05-27.

- OCLC 1162187814.

- ISBN 978-3-89821-965-5 – via Google Books.

Further reading

- Hardeman, Hilde (1994). Coming to Terms with the Soviet Regime: The "Changing Signposts" Movement Among Russian Emigrés in the Early 1920s. NIU Series in Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies. Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 9780875801872.