Nanban trade: Difference between revisions

Extended confirmed users 2,874 edits No edit summary |

Extended confirmed users 2,874 edits No edit summary |

||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

Ever since 1514 that the Portuguese had traded with [[Ming dynasty|China]] from [[Portuguese Malacca|Malacca]], and the year after the first Portuguese landfall in Japan, trade commenced between Malacca, China, and Japan. The Chinese Emperor had decreed an embargo against Japan as a result of piratical [[wokou]] raids against China - consequently, Chinese goods were in scarce supply in Japan and so, the Portuguese found a lucrative opportunity to act as middlemen between the two realms.<ref>BOXER: ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=2R4DA2lip9gC&lpg=PP1&dq=cr%20boxer%20the%20christian%20century&pg=PA91#v=onepage&q&f=false The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650]'', 1951, p. 91</ref> |

Ever since 1514 that the Portuguese had traded with [[Ming dynasty|China]] from [[Portuguese Malacca|Malacca]], and the year after the first Portuguese landfall in Japan, trade commenced between Malacca, China, and Japan. The Chinese Emperor had decreed an embargo against Japan as a result of piratical [[wokou]] raids against China - consequently, Chinese goods were in scarce supply in Japan and so, the Portuguese found a lucrative opportunity to act as middlemen between the two realms.<ref>BOXER: ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=2R4DA2lip9gC&lpg=PP1&dq=cr%20boxer%20the%20christian%20century&pg=PA91#v=onepage&q&f=false The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650]'', 1951, p. 91</ref> |

||

Trade with Japan was initially open to any, but in 1550, the Portuguese Crown monopolized the rights to trade with Japan.<ref>BOXER: ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=2R4DA2lip9gC&lpg=PP1&dq=cr%20boxer%20the%20christian%20century&pg=PA92#v=onepage&q&f=false The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650]'', 1951, p. 91</ref> Henceforth, once a year a ''fidalgo'' was awarded the rights for a single trade venture to Japan with considerable privileges, such as the title of ''captain-major of the voyage to Japan'', with authority over any Portuguese subjects in China or Japan while he was in port, and the right to sell his post. His ship would set sail from Goa, called at Malacca and China before proceeding to Japan and back. |

Trade with Japan was initially open to any, but in 1550, the Portuguese Crown monopolized the rights to trade with Japan.<ref>BOXER: ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=2R4DA2lip9gC&lpg=PP1&dq=cr%20boxer%20the%20christian%20century&pg=PA92#v=onepage&q&f=false The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650]'', 1951, p. 91</ref> Henceforth, once a year a ''fidalgo'' was awarded the rights for a single trade venture to Japan with considerable privileges, such as the title of ''captain-major of the voyage to Japan'', with authority over any Portuguese subjects in China or Japan while he was in port, and the right to sell his post, should he lack the necessary funds to undertake the enterprise. He could charter a royal vessel or purchase his own, at about 40,000 xerafins.<ref>BOXER: ''[https://archive.org/details/THECHRISTIANCENTURYINJAPAN15491650CRBOXER/page/n335 The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650]'', 1951, p. 303</ref> His ship would set sail from Goa, called at Malacca and China before proceeding to Japan and back. |

||

In 1554, captain-major Leonel de Sousa [[Luso-Chinese agreement (1554)|negotiated with Chinese authorities the re-legalization of Portuguese trade in China]], which was followed by the foundation of [[Macau]] in 1557 to support this trade. <ref>BOXER: ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=2R4DA2lip9gC&lpg=PP1&dq=cr%20boxer%20the%20christian%20century&pg=PA92#v=onepage&q&f=false The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650]'', 1951, p. 92</ref> |

In 1554, captain-major Leonel de Sousa [[Luso-Chinese agreement (1554)|negotiated with Chinese authorities the re-legalization of Portuguese trade in China]], which was followed by the foundation of [[Macau]] in 1557 to support this trade. <ref>BOXER: ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=2R4DA2lip9gC&lpg=PP1&dq=cr%20boxer%20the%20christian%20century&pg=PA92#v=onepage&q&f=false The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650]'', 1951, p. 92</ref> |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

In the 16th century, large junks belonging to private owners from Macau often accompanied the great ship to Japan, about two or three; these could reach about 400 or 500 tons burden.<ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=pOoYAAAAIAAJ&dq=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=somas The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640]'' p. 14</ref> After 1618, the Portuguese switched to using smaller and more maneuverable [[pinnace]]s and [[galliot]]s, to avoid interception from Dutch raiders.<ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=pOoYAAAAIAAJ&q=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&dq=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjukOv6uK3iAhWLnhQKHaLFCZMQ6AEIKjAA The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640]'' p.14</ref> |

In the 16th century, large junks belonging to private owners from Macau often accompanied the great ship to Japan, about two or three; these could reach about 400 or 500 tons burden.<ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=pOoYAAAAIAAJ&dq=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=somas The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640]'' p. 14</ref> After 1618, the Portuguese switched to using smaller and more maneuverable [[pinnace]]s and [[galliot]]s, to avoid interception from Dutch raiders.<ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=pOoYAAAAIAAJ&q=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&dq=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjukOv6uK3iAhWLnhQKHaLFCZMQ6AEIKjAA The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640]'' p.14</ref> |

||

===Traded items=== |

|||

===Portuguese trade in Japanese slaves=== |

|||

{{see also|Slavery in Portugal}} |

|||

By far the most valuable commodities exchanged in the "nanban trade" were Chinese silks for Japanese silver, which was then traded in China for more silk.<ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=pOoYAAAAIAAJ&q=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&dq=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjukOv6uK3iAhWLnhQKHaLFCZMQ6AEIKjAA The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640]'' p.5</ref> Although accurate statistics are lacking, it's been estimated that roughly half of Japan's yearly silver output was exported, most of it through the Portuguese, amounting to about 18 - 20 tons in silver [[bullion]].<ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=pOoYAAAAIAAJ&q=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&dq=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjukOv6uK3iAhWLnhQKHaLFCZMQ6AEIKjAA The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640]'' p. 7</ref> The English merchant [[Peter Mundy]] estimated that Portuguese investment at Canton ascended to 1,500,000 silver [[tael|taels]] or 1,000,000 Spanish [[Spanish dollar|reales]].<ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=pOoYAAAAIAAJ&q=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&dq=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjukOv6uK3iAhWLnhQKHaLFCZMQ6AEIKjAA The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640]'' p.6</ref> The Portuguese also exported surplus silk from Macau to Goa and Europe via Manila.<ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=pOoYAAAAIAAJ&q=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&dq=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjukOv6uK3iAhWLnhQKHaLFCZMQ6AEIKjAA The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640]'' p.6</ref> <ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=pOoYAAAAIAAJ&q=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&dq=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjukOv6uK3iAhWLnhQKHaLFCZMQ6AEIKjAA The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640]'' p.7-8</ref> |

|||

After the Portuguese first made contact with Japan in 1543, a large scale slave trade developed in which Portuguese purchased Japanese as slaves in Japan and sold them to various locations overseas, including Portugal itself, throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.<ref>{{cite news |last= HOFFMAN|first= MICHAEL|date=May 26, 2013|title=The rarely, if ever, told story of Japanese sold as slaves by Portuguese traders |url=http://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2013/05/26/books/the-rarely-if-ever-told-story-of-japanese-sold-as-slaves-by-portuguese-traders/|newspaper=The Japan Times |location= |publisher= |accessdate=2014-03-02 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last= |first= |date=May 10, 2007|title=Europeans had Japanese slaves, in case you didn't know ... |url=http://www.japanprobe.com/2007/05/10/europeans-had-japanese-slaves-in-case-you-didnt-know/|newspaper=Japan Probe |location= |publisher= |accessdate=2014-03-02 }}</ref> Many documents mention the large slave trade along with protests against the enslavement of Japanese. Japanese slaves are believed to be the first of their nation to end up in Europe, and the Portuguese purchased large numbers of Japanese slave girls to bring to Portugal [[Sexual slavery|for sexual purposes]] (see: [[Asian fetish]]), as noted by the Church in 1555. [[Sebastian of Portugal|King Sebastian]] feared that it was having a negative effect on Catholic [[proselytization]] since the slave trade in Japanese was growing to massive proportions, so he commanded that it be banned in 1571.<ref>{{cite web|jstor=25066328|title=Monumenta Nipponica (Slavery in Medieval Japan)|last=Nelson|first=Thomas|volume=Vol. 59|number=No. 4|date=Winter 2004|page=463|publisher=Sophia University.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|publisher=Sophia University|year=2004|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XoQMAQAAMAAJ&q=Portuguese+and+other+Occidental+sources+are+replete+with+records+of+the+export+of+Japanese+slaves+in+the+second+half+of+the+sixteenth+century.+A+few+examples+should+serve+to+illustrate+this+point.+Very+probably,+the+first+Japanese+who+set+foot+in+Europe+were+slaves.+As+early+as+1555,+complaints+were+made+by+the+Church+that+Portuguese+merchants+were+taking+Japanese+slave+girls+with+them+back+to+Portugal+and+living+with+them+there+in+sin.+By+1571,+the+trade+was+being+conducted+on+such+a+scale+that+King+Sebastian+of+Portugal+felt+obliged+to+issue+an+order+prohibiting+it+lest+it+hinder+Catholic+missionary+activity+in+Kyushsu.&dq=Portuguese+and+other+Occidental+sources+are+replete+with+records+of+the+export+of+Japanese+slaves+in+the+second+half+of+the+sixteenth+century.+A+few+examples+should+serve+to+illustrate+this+point.+Very+probably,+the+first+Japanese+who+set+foot+in+Europe+were+slaves.+As+early+as+1555,+complaints+were+made+by+the+Church+that+Portuguese+merchants+were+taking+Japanese+slave+girls+with+them+back+to+Portugal+and+living+with+them+there+in+sin.+By+1571,+the+trade+was+being+conducted+on+such+a+scale+that+King+Sebastian+of+Portugal+felt+obliged+to+issue+an+order+prohibiting+it+lest+it+hinder+Catholic+missionary+activity+in+Kyushsu.&hl=en&sa=X&ei=j3YVU9-ZKImZ0QHKsIHQCg&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAA|quote= |volume=|page=463|title=Monumenta Nipponica: Studies on Japanese Culture, Past and Present, Volume 59, Issues 3–4|isbn=|others=Jōchi Daigaku|edition=|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref> |

|||

Nonetheless, numerous other items were also transactioned, such as gold, Chinese [[porcelain]], [[musk]], and [[rhubarb]]; Arabian horses, Bengal tigers and [[peacocks]]; fine Indian scarlet cloths, [[calico]] and [[cintz]]; European manufactured items such as Flemish clocks and Venetian glass and Portuguese wine and [[rapiers]];<ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books/about/Fidalgos_in_the_Far_East_1550_1770.html?id=qUAsAAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y Fidalgos on the Far-East 1550-1770]'', Oxford, 1968, p.10</ref><ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books/about/Fidalgos_in_the_Far_East_1550_1770.html?id=qUAsAAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y Fidalgos on the Far-East 1550-1770]'', Oxford, 1968, p.15</ref> in return for Japanese copper, [[lacquer]] and [[lacquerware]] or weapons (as purely exotic items to be displayed in Europe).<ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books/about/Fidalgos_in_the_Far_East_1550_1770.html?id=qUAsAAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y Fidalgos on the Far-East 1550-1770]'', Oxford, 1968, p.16</ref> |

|||

Japanese slave women were also ocassionally sold as [[concubine]]s to black African crewmembers, along with their European counterparts serving on Portuguese ships trading in Japan, as mentioned by Luis Cerqueira, a Portuguese Jesuit, in a 1598 document.<ref>{{cite book|publisher=Taylor & Francis|year=2004|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4z_JJfG-hyYC&pg=PA408&dq=japanese+slaves+portuguese&hl=en&sa=X&ei=xYcVU5uJN5GU0gGF44H4Bw&ved=0CD8Q6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=japanese%20slaves%20portuguese&f=false|quote= |volume=|page=408|title=Race, Ethnicity and Migration in Modern Japan: Imagined and imaginary minorites|isbn=0-415-20857-2|editor=Michael Weiner|edition=illustrated|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref> Japanese slaves were brought by the Portuguese to [[Macau]], where some of them not only ended up being enslaved to Portuguese, but as slaves to other slaves, with the Portuguese owning Malay and African slaves, who in turn owned Japanese slaves of their own.<ref>{{cite book|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2005|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TMZMAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA479&dq=japanese+slaves+portuguese&hl=en&sa=X&ei=xYcVU5uJN5GU0gGF44H4Bw&ved=0CDUQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=japanese%20slaves%20portuguese&f=false|quote= |volume=|page=479|title=Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience|isbn=0-19-517055-5|editors=Kwame Anthony Appiah, Henry Louis Gates, Jr.|edition=illustrated|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2010|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=A0XNvklcqbwC&pg=PA187&dq=japanese+slaves+portuguese&hl=en&sa=X&ei=xYcVU5uJN5GU0gGF44H4Bw&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=japanese%20slaves%20portuguese&f=false|quote= |volume=|page=187|title=Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 1|isbn=0-19-533770-0|editors=Anthony Appiah, Henry Louis Gates|edition=illustrated|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref> |

|||

Japanese (and Koreans) captured in battle were also sold by their compatriots to the Portuguese as slaves, but the Japanese would also sell family members they could not afford to sustain because of the civil-war. According to prof. Boxer, both old and modern Asian authors have "conveniently overlooked" their part in the enslavement of their countrymen.<ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books/about/Fidalgos_in_the_Far_East_1550_1770.html?id=qUAsAAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y Fidalgos on the Far-East 1550-1770]'', Oxford, 1968, p.223</ref> They were well regarded for their skills and warlike character, and some ended as far as India and even Europe, some armed retainers or as concubines or slaves to other slaves of the Portuguese.<ref>{{cite book|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2005|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TMZMAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA479&dq=japanese+slaves+portuguese&hl=en&sa=X&ei=xYcVU5uJN5GU0gGF44H4Bw&ved=0CDUQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=japanese%20slaves%20portuguese&f=false|quote= |volume=|page=479|title=Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience|isbn=0-19-517055-5|editors=Kwame Anthony Appiah, Henry Louis Gates, Jr.|edition=illustrated|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2010|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=A0XNvklcqbwC&pg=PA187&dq=japanese+slaves+portuguese&hl=en&sa=X&ei=xYcVU5uJN5GU0gGF44H4Bw&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=japanese%20slaves%20portuguese&f=false|quote= |volume=|page=187|title=Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 1|isbn=0-19-533770-0|editors=Anthony Appiah, Henry Louis Gates|edition=illustrated|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref> In 1571, [[King Sebastian of Portugal]] issued a ban on the enslavent of both Chinese and Japanese, probably fearing the negative effects it might have on proselytization efforts as well as the standing diplomacy between the countries.<ref>{{harvnb|Dias|2007|p=71}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|jstor=25066328|title=Monumenta Nipponica (Slavery in Medieval Japan)|last=Nelson|first=Thomas|volume=Vol. 59|number=No. 4|date=Winter 2004|page=463|publisher=Sophia University.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|publisher=Sophia University|year=2004|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XoQMAQAAMAAJ&q=Portuguese+and+other+Occidental+sources+are+replete+with+records+of+the+export+of+Japanese+slaves+in+the+second+half+of+the+sixteenth+century.+A+few+examples+should+serve+to+illustrate+this+point.+Very+probably,+the+first+Japanese+who+set+foot+in+Europe+were+slaves.+As+early+as+1555,+complaints+were+made+by+the+Church+that+Portuguese+merchants+were+taking+Japanese+slave+girls+with+them+back+to+Portugal+and+living+with+them+there+in+sin.+By+1571,+the+trade+was+being+conducted+on+such+a+scale+that+King+Sebastian+of+Portugal+felt+obliged+to+issue+an+order+prohibiting+it+lest+it+hinder+Catholic+missionary+activity+in+Kyushsu.&dq=Portuguese+and+other+Occidental+sources+are+replete+with+records+of+the+export+of+Japanese+slaves+in+the+second+half+of+the+sixteenth+century.+A+few+examples+should+serve+to+illustrate+this+point.+Very+probably,+the+first+Japanese+who+set+foot+in+Europe+were+slaves.+As+early+as+1555,+complaints+were+made+by+the+Church+that+Portuguese+merchants+were+taking+Japanese+slave+girls+with+them+back+to+Portugal+and+living+with+them+there+in+sin.+By+1571,+the+trade+was+being+conducted+on+such+a+scale+that+King+Sebastian+of+Portugal+felt+obliged+to+issue+an+order+prohibiting+it+lest+it+hinder+Catholic+missionary+activity+in+Kyushsu.&hl=en&sa=X&ei=j3YVU9-ZKImZ0QHKsIHQCg&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAA|quote= |volume=|page=463|title=Monumenta Nipponica: Studies on Japanese Culture, Past and Present, Volume 59, Issues 3–4|isbn=|others=Jōchi Daigaku|edition=|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref> The shogun of Japan Toyotomi Heideyoshi (who also participated in the enslavement of Koreans<ref>{{cite book|publisher=Routledge|year=2002|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FliQAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA170&dq=Hideyoshi+korean+slaves&hl=en&sa=X&ei=u4cVU9vFFtTukQf6-oDABA&ved=0CC0Q6AEwATgK#v=onepage&q=Hideyoshi%20korean%20slaves&f=false|quote= |volume=|page=170|title=Tanegashima – The Arrival of Europe in Japan|isbn=1-135-78871-5|author=Olof G. Lidin|edition=|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|publisher=University of California Press|year=2012|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6yjTKhcy0jYC&pg=PT60&dq=Hideyoshi+korean+portuguese+slaves&hl=en&sa=X&ei=wIcVU6fRO6TJ0wHL74HYBg&ved=0CEgQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=Hideyoshi%20korean%20portuguese%20slaves&f=false|quote= |volume=Volume 21 of Asia: Local Studies / Global Themes|page=|title=Selling Women: Prostitution, Markets, and the Household in Early Modern Japan|isbn=0-520-95238-3|author=Amy Stanley|others=Matthew H. Sommer|edition=|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref>) enforced the end of the enslavement of his countrymen starting in 1587 and it was suppressed shortly thereafter.<ref>{{cite book|publisher=Sophia University|year=2004|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wAdDAAAAYAAJ&q=It+has+come+to+our+attention+that+Portuguese,+Siamese,+and+Cambodians+who+come+to+our+shores+to+trade+are+buying+many+people,+taking+them+captive+to+their+kingdoms,+ripping+Japanese+away+from+their+homeland,+families,+children+and+friends.+This+is+insufferable.+Thus,+would+the+Padre+ensure+that+all+those+Japanese+who+have+up+until+now+been+sold+in+India+and+other+distant+places+be+returned+again+to+Japan.+If+this+is+not+possible,+because+they+are+far+away+in+remote+kingdoms,+then+at+least+have+the+Portuguese+set+free+the+people+whom+they+have+bought+recently.+I+will+provide+the+money+necessary+to+do+this.&dq=It+has+come+to+our+attention+that+Portuguese,+Siamese,+and+Cambodians+who+come+to+our+shores+to+trade+are+buying+many+people,+taking+them+captive+to+their+kingdoms,+ripping+Japanese+away+from+their+homeland,+families,+children+and+friends.+This+is+insufferable.+Thus,+would+the+Padre+ensure+that+all+those+Japanese+who+have+up+until+now+been+sold+in+India+and+other+distant+places+be+returned+again+to+Japan.+If+this+is+not+possible,+because+they+are+far+away+in+remote+kingdoms,+then+at+least+have+the+Portuguese+set+free+the+people+whom+they+have+bought+recently.+I+will+provide+the+money+necessary+to+do+this.&hl=en&sa=X&ei=Z3cVU_IElIuQB_2RgNAC&ved=0CCgQ6AEwAA|quote= |volume=|page=465|title=Monumenta Nipponica|isbn=|others=Jōchi Daigaku|edition=|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|publisher=Columbia University Press|year=2013|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lani3dFCC9UC&pg=PA144&dq=Hideyoshi+korean+portuguese+slaves&hl=en&sa=X&ei=wIcVU6fRO6TJ0wHL74HYBg&ved=0CDwQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=Hideyoshi%20korean%20portuguese%20slaves&f=false|quote= |volume=|page=144|title=Religion in Japanese History|isbn=0-231-51509-X|author=Joseph Mitsuo Kitagawa|edition=illustrated, reprint|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|publisher=Routledge|year=2013|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=J0KvyZp9VKAC&pg=PA37&dq=japanese+slaves+portuguese&hl=en&sa=X&ei=xYcVU5uJN5GU0gGF44H4Bw&ved=0CFwQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=japanese%20slaves%20portuguese&f=false|quote= |volume=|page=37|title=Nature and Origins of Japanese Imperialism|isbn=1-134-91843-7|author=Donald Calman|edition=|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref> |

|||

The overall profits from the Japan trade, carried on through the black ship, was estimated to ascend to over 600,000 ''cruzados'', according to various contemporary authors such as [[Diogo do Couto]], [[Jan Huygen van Linschoten]] and [[William Adams]]. A captain-major who invested at Goa 20,000 ''cruzados'' to this venture could expect 150,000 ''cruzados'' in profits upon returning.<ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=pOoYAAAAIAAJ&q=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&dq=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjukOv6uK3iAhWLnhQKHaLFCZMQ6AEIKjAA The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640]'' p.8</ref> The value of Portuguese exports from Nagasaki during the 16th century were estimated to ascend to over 1,000,000 ''cruzados'', reaching as many as 3,000,000 in 1637.<ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=pOoYAAAAIAAJ&q=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&dq=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjukOv6uK3iAhWLnhQKHaLFCZMQ6AEIKjAA The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640]'' p.169</ref> The Dutch estimated this was the equivalent of some 6,100,000 [[Dutch guilder|guilders]], almost as much as the entire founding capital of the [[VOC]] (6,500,000 guilders).<ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=pOoYAAAAIAAJ&q=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&dq=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjukOv6uK3iAhWLnhQKHaLFCZMQ6AEIKjAA The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640]'' p.170</ref> VOC profits in all of Asia amounted to "just" about 1,200,000 guilders, all its assets worth 9,500,000 guilders. <ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=pOoYAAAAIAAJ&q=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&dq=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjukOv6uK3iAhWLnhQKHaLFCZMQ6AEIKjAA The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640]'' p.170</ref> |

|||

Some Korean slaves were bought by the Portuguese and brought back to Portugal from Japan, where they had been among the tens of thousands of Korean prisoners of war transported to Japan during the [[Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98)]].<ref>{{cite book|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=2003|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=k9Ro7b0tWz4C&pg=PA277&dq=Hideyoshi+korean+slaves+guns+silk&hl=en&sa=X&ei=j4QVU-aVIZLo0wG1voCoAg&ved=0CDMQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=Hideyoshi%20korean%20slaves%20guns%20silk&f=false|quote= |volume=|page=277|title=The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective|isbn=0-521-52750-3|editors=Robert Gellately, Ben Kiernan|edition=reprint|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|publisher=Harvard University, Edwin O. Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies|year=2001|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=afCfAAAAMAAJ&q=Other+Koreans+were+sold+as+slaves,+or+exchanged+for+guns,+silk,+or+other+prized+foreign+goods,+either+directly+or+via+third+country+slave+traders,+to+many+countries,+some+finishing+up+as+far+away+as+Portugal.+It+seems+to+me+in+short+that+a+case+...&dq=Other+Koreans+were+sold+as+slaves,+or+exchanged+for+guns,+silk,+or+other+prized+foreign+goods,+either+directly+or+via+third+country+slave+traders,+to+many+countries,+some+finishing+up+as+far+away+as+Portugal.+It+seems+to+me+in+short+that+a+case+...&hl=en&sa=X&ei=zZIVU8C2Kc_LkQfp9ICABg&ved=0CCgQ6AEwAA|quote= |volume=|page=18|title=Reflections on Modern Japanese History in the Context of the Concept of "genocide"|isbn=|author=Gavan McCormack|others=Edwin O. Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies|edition=|issue=Issue 2001, Part 1 of Occasional papers in Japanese studies|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref> Historians pointed out that at the same time Hideyoshi expressed his indignation and outrage at the Portuguese trade in Japanese slaves, he himself was engaging in a mass slave trade of Korean prisoners of war in Japan.<ref>{{cite book|publisher=Routledge|year=2002|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FliQAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA170&dq=Hideyoshi+korean+slaves&hl=en&sa=X&ei=u4cVU9vFFtTukQf6-oDABA&ved=0CC0Q6AEwATgK#v=onepage&q=Hideyoshi%20korean%20slaves&f=false|quote= |volume=|page=170|title=Tanegashima – The Arrival of Europe in Japan|isbn=1-135-78871-5|author=Olof G. Lidin|edition=|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|publisher=University of California Press|year=2012|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6yjTKhcy0jYC&pg=PT60&dq=Hideyoshi+korean+portuguese+slaves&hl=en&sa=X&ei=wIcVU6fRO6TJ0wHL74HYBg&ved=0CEgQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=Hideyoshi%20korean%20portuguese%20slaves&f=false|quote= |volume=Volume 21 of Asia: Local Studies / Global Themes|page=|title=Selling Women: Prostitution, Markets, and the Household in Early Modern Japan|isbn=0-520-95238-3|author=Amy Stanley|others=Matthew H. Sommer|edition=|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref> [[Kirishitan|Japanese Christian Daimyos]] were mainly responsible for selling to the Portuguese their fellow Japanese. Japanese women and Japanese men, Javanese, [[Chinese people in Portugal|Chinese]], and [[Indians in Portugal|Indians]] were all sold as [[Slavery in Portugal|slaves in Portugal]].<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=l2qSNQnlQGcC&pg=PA103&dq=sul+portugal+chineses+escravos#v=onepage&q=sul%20portugal%20chineses%20escravos&f=false|title=Chòque luso no Japão dos séculos XVI e XVII|author=José Yamashiro|year=1989|publisher=IBRASA|page=103|isbn=85-348-1068-0|accessdate=14 July 2010}}</ref> [[Macau]] received an influx of African slaves, Japanese slaves as well as [[Catholic Church in South Korea|Christian Korean slaves]] who were [[Macanese people#The Portuguese Period|bought by the Portuguese from the Japanese]] after they were taken prisoner during the [[Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598)|Japanese invasions of Korea]] in the era of [[Hideyoshi]].<ref>{{cite book|publisher=BRILL|year=2015|location= |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=A3HsCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA93#v=onepage&q&f=false |quote= |volume=|page=93|title=Setting Off from Macau: Essays on Jesuit History during the Ming and Qing Dynasties|author=Kaijian Tang|isbn=9004305521|editor=|edition= |accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref> |

|||

After 1592, Portuguese trade was challenged by Japanese [[Red Seal Ships]], Spanish ships from Manila after 1600 (until 1620<ref>BOXER: ''[https://archive.org/details/THECHRISTIANCENTURYINJAPAN15491650CRBOXER/page/n333 The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650]'', 1951, p. 301</ref>), the Dutch after 1609 and the English in 1613 (until 1623<ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.pt/books?id=pOoYAAAAIAAJ&q=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&dq=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjukOv6uK3iAhWLnhQKHaLFCZMQ6AEIKjAA The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640]'' p.4</ref>). Nonetheless, it was found that neither the Dutch nor the Spanish could effectively replace the Portuguese, due to the latter's privileged access to Chinese markets and investors through Macau.<ref>BOXER: ''[https://archive.org/details/THECHRISTIANCENTURYINJAPAN15491650CRBOXER/page/n335 The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650]'', 1951, p. 303</ref> The Portuguese were only definitively banned in 1638 after the [[Shimabara Rebellion]], on the grounds that they smuggled priests into Japan aboard their vessels. |

|||

Fillippo Sassetti saw some Chinese and Japanese slaves in Lisbon among the large slave community in 1578, although most of the slaves were blacks.<ref>{{cite book|publisher=Penguin Books|year=1985|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?ei=DN6hT8zdGKS16AHNsY30CA&id=YmauWWluaqcC&dq=sassetti+chinese+slaves&q=sassetti+scattering+chinese+slaves|quote=countryside.16 Slaves were everywhere in Lisbon, according to the Florentine merchant Filippo Sassetti, who was also living in the city during 1578. Black slaves were the most numerous, but there were also a scattering of Chinese |volume=|page=208|title=The memory palace of Matteo Ricci|author=Jonathan D. Spence|isbn=0-14-008098-8|editor=|edition=illustrated, reprint|accessdate=2012-05-05}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|language=Portuguese|publisher=UNICAMP. Universidade Estadual de Campinas|year=1999|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?ei=_OGhT5PyGobA6AGCh-33CA&id=wNZ6AAAAMAAJ&dq=Muitos+desses+escravos+chineses+de+Lisboa+tinham+sido+sequestrados+ainda+em+crian%C3%A7a+em+Macau+e+vendidos+%28n%C3%A3o+raro+pelos+pr%C3%B3prios+pais%29+aos+lusitanos.+O+c%C3%A9lebre+jesu%C3%ADta+padre+Matteo+Ricci+estava+a+par+do+com%C3%A9rcio+de+escravos+chineses+na&q=escravos+chineses+lisboa+sequestrados|quote=Idéias e costumes da China podem ter-nos chegado também através de escravos chineses, de uns poucos dos quais sabe-se da presença no Brasil de começos do Setecentos.17 Mas não deve ter sido através desses raros infelizes que a influência chinesa nos atingiu, mesmo porque escravos chineses (e também japoneses) já existiam aos montes em Lisboa por volta de 1578, quando Filippo Sassetti visitou a cidade,18 apenas suplantados em número pelos africanos. Parece aliás que aos últimos cabia o trabalho pesado, ficando reservadas aos chins tarefas e funções mais amenas, inclusive a de em certos casos secretariar autoridades civis, religiosas e militares. |volume=|page=19|title=A China no Brasil: influências, marcas, ecos e sobrevivências chinesas na sociedade e na arte brasileiras|author=José Roberto Teixeira Leite|isbn=85-268-0436-7|editor=|edition=|accessdate=2012-05-05}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|publisher=Himalaya Pub. House|year=1992|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?ei=I9-hT_HxO7Ce6QHb75zbCA&id=PHPaAAAAMAAJ&dq=respectable+families+for+sale+as+slaves+in+India.36+Chinese+slaves+and+domestic+servants+were+for+the+most+part+kidnapped+from+their+villages+when+they+were+young&q=circa+1580|quote=ing Chinese as slaves, since they are found to be very loyal, intelligent and hard working' ... their culinary bent was also evidently appreciated. The Florentine traveller Fillippo Sassetti, recording his impressions of Lisbon's enormous slave population circa 1580, states that the majority of the Chinese there were employed as cooks. |volume=|page=18|title=Slavery in Portuguese India, 1510–1842|author=Jeanette Pinto|isbn=|editor=|edition=|accessdate=2012-05-05}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|publisher=2, illustrated, reprint|year=1968|location=|url=https://books.google.com/books?ei=xvylT8XlEJDUgAflqoS3AQ&id=qUAsAAAAMAAJ&dq=The+Florentine+traveller+Filipe+Sassetti+recording+his+impressions+of+Lisbon%27s+enormous+slave+population+circa+1580%2C+states+that+the+majority+of+the+Chinese+there+were+employed+as+cooks&q=enormous+majority|quote=be very loyal, intelligent, and hard-working. Their culinary bent (not for nothing is Chinese cooking regarded as the Asiatic equivalent to French cooking in Europe) was evidently appreciated. The Florentine traveller Filipe Sassetti recording his impressions of Lisbon's enormous slave population circa 1580, states that the majority of the Chinese there were employed as cooks. Dr. John Fryer, who gives us an interesting ... |volume=|page=225|title=Fidalgos in the Far East 1550–1770|author=Charles Ralph Boxer|isbn=|editor=|edition=2, illustrated, reprint|accessdate=2012-05-05}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|publisher=UNICAMP. Universidade Estadual de Campinas|year=1999|location=|language=Portuguese|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MyEsAAAAYAAJ&q=Idéias+e+costumes+da+China+podem+ter-nos+chegado+também+através+de+escravos+chineses,+de+uns+poucos+dos+quais+sabe-se+da+presença+no+Brasil+de+começos+do+Setecentos.17+Mas+não+deve+ter+sido+através+desses+raros+infelizes+que+a+influência+chinesa+nos+atingiu,+mesmo+porque+escravos+chineses+(e+também+japoneses)+já+existiam+aos+montes+em+Lisboa+por+volta+de+1578,+quando+Filippo+Sassetti+visitou+a+cidade,18+apenas+suplantados+em+número+pelos+africanos.+Parece+aliás+que+aos+últimos+cabia+o+trabalho+pesado,+ficando+reservadas+aos+chins+tarefas+e+funções+mais+amenas,+inclusive+a+de+em+certos+casos+secretariar+autoridades+civis,+religiosas+e+militares.&dq=Idéias+e+costumes+da+China+podem+ter-nos+chegado+também+através+de+escravos+chineses,+de+uns+poucos+dos+quais+sabe-se+da+presença+no+Brasil+de+começos+do+Setecentos.17+Mas+não+deve+ter+sido+através+desses+raros+infelizes+que+a+influência+chinesa+nos+atingiu,+mesmo+porque+escravos+chineses+(e+também+japoneses)+já+existiam+aos+montes+em+Lisboa+por+volta+de+1578,+quando+Filippo+Sassetti+visitou+a+cidade,18+apenas+suplantados+em+número+pelos+africanos.+Parece+aliás+que+aos+últimos+cabia+o+trabalho+pesado,+ficando+reservadas+aos+chins+tarefas+e+funções+mais+amenas,+inclusive+a+de+em+certos+casos+secretariar+autoridades+civis,+religiosas+e+militares.&hl=en&sa=X&ei=gH8VU4-EDoT1kQeZjIC4BA&ved=0CCgQ6AEwAA|quote= |volume=|page=19|title=A China No Brasil: Influencias, Marcas, Ecos E Sobrevivencias Chinesas Na Sociedade E Na Arte Brasileiras|isbn=85-268-0436-7|author=José Roberto Teixeira Leite|editor=|edition=|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref> |

|||

The Portuguese "highly regarded" Asian slaves like Chinese and Japanese much more "than slaves from sub-Saharan Africa".<ref>{{cite book|publisher=Macmillan Reference USA, Simon & Schuster Macmillan|year=1998|location=|language=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5s0YAAAAIAAJ&q=In+the+sixteenth+century+North+African+and+black+African+slaves+were+joined+by+captives+from+Brazil,+India,+Southeast+Asia,+China,+and+Japan.+Asian+slaves,+especially+Japanese+and+Chinese,+were+much+more+highly+regarded+than+slaves+from+sub-+Saharan+Africa,+who+in+turn+were+valued+and+trusted+more+than+Muslim+slaves+from+North+Africa.&dq=In+the+sixteenth+century+North+African+and+black+African+slaves+were+joined+by+captives+from+Brazil,+India,+Southeast+Asia,+China,+and+Japan.+Asian+slaves,+especially+Japanese+and+Chinese,+were+much+more+highly+regarded+than+slaves+from+sub-+Saharan+Africa,+who+in+turn+were+valued+and+trusted+more+than+Muslim+slaves+from+North+Africa.&hl=en&sa=X&ei=F4cVU73eApLv0QGWl4DwDQ&ved=0CCgQ6AEwAA|quote= |volume=|page=737|title=Macmillan encyclopedia of world slavery, Volume 2|isbn=0-02-864781-5|author=Paul Finkelman|editor=Paul Finkelman, Joseph Calder Miller|edition=|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Finkelman|Miller|1998|p=737}}</ref> The Portuguese attributed qualities like intelligence and industriousness to Chinese and Japanese slaves which is why they favored them more.<ref>{{cite book|publisher=Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.|year=2012|location=|language=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=n2DUmk9XUsMC&pg=RA1-PT294&dq=Japanese,+and+Chinese,+slaves+were+greatly+appreciated+by+the+Portuguese+because+they+were+highly+intelligent+and+industrious&hl=en&sa=X&ei=AokVU_azIeGX0QGO44DACg&ved=0CDAQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Japanese%2C%20and%20Chinese%2C%20slaves%20were%20greatly%20appreciated%20by%20the%20Portuguese%20because%20they%20were%20highly%20intelligent%20and%20industrious&f=false|quote= |volume=Volume 25 of 3: Works, Hakluyt Society Hakluyt Society|page=|title=Japanese Travellers in Sixteenth-century Europe: A Dialogue Concerning the Mission of the Japanese Ambassadors to the Roman Curia (1590)|isbn=1-4094-7223-X|author=Duarte de Sande|editor=Derek Massarella|issue=Issue 25 of Works issued by the Hakluyt Society|edition=|issn=0072-9396|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=1982|location=|language=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g0TCPWGGVqgC&pg=PA168#v=onepage&q&f=false|quote= |volume=Volume 25 of 3: Works, Hakluyt Society Hakluyt Society|page=168|title=A Social History of Black Slaves and Freedmen in Portugal, 1441–1555|isbn=0-521-23150-7|author=A. C. de C. M. Saunders|editor=|issue=|edition=illustrated|issn=|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|publisher=Himalaya Pub. House|year=1992|location=|language=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PHPaAAAAMAAJ&q=Jean+Mocquet+in+his+book+Old+China+Hands+records+that+the+Portuguese+were+particularly+desirous+of+securing+Chinese+as+slaves,+since+'they+are+found+to+be+very+loyal,+intelligent+and+hard+working'&dq=Jean+Mocquet+in+his+book+Old+China+Hands+records+that+the+Portuguese+were+particularly+desirous+of+securing+Chinese+as+slaves,+since+'they+are+found+to+be+very+loyal,+intelligent+and+hard+working'&hl=en&sa=X&ei=KokVU4npJqvh0wGdq4C4Dw&ved=0CCgQ6AEwAA|quote= |volume=|page=18|title=Slavery in Portuguese India, 1510–1842|isbn=|author=Jeanette Pinto|editor=|issue=|edition=|issn=|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|publisher=Oxford U.P.|year=1968|location=|language=|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qUAsAAAAMAAJ&q=Jean+Mocquet+in+his+book+Old+China+Hands+records+that+the+Portuguese+were+particularly+desirous+of+securing+Chinese+as+slaves,+since+'they+are+found+to+be+very+loyal,+intelligent+and+hard+working'&dq=Jean+Mocquet+in+his+book+Old+China+Hands+records+that+the+Portuguese+were+particularly+desirous+of+securing+Chinese+as+slaves,+since+'they+are+found+to+be+very+loyal,+intelligent+and+hard+working'&hl=en&sa=X&ei=KokVU4npJqvh0wGdq4C4Dw&ved=0CCwQ6AEwAQ|quote= |volume=|page=225|title=Fidalgos in the Far East 1550–1770|isbn=|author=Charles Ralph Boxer|editor=|issue=|edition=2, illustrated, reprint|issn=|accessdate=2014-02-02}}</ref> |

|||

In 1571 a law was passed by Portugal banning the selling and buying of Chinese and Japanese slaves.<ref>{{harvnb|Dias|2007|p=71}}</ref> |

|||

== Dutch trade == |

== Dutch trade == |

||

Revision as of 15:46, 23 May 2019

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Japan |

|---|

|

The Nanban trade (南蛮貿易, Nanban bōeki, "Southern barbarian trade") or the Nanban trade period (南蛮貿易時代, Nanban bōeki jidai, "Southern barbarian trade period") in the

Nanban (南蛮, "southern barbarian") is a

First contacts

Japanese accounts of Europeans

This section includes a improve this section by introducing more precise citations. (March 2019) ) |

Following contact with the Portuguese on Tanegashima in 1542, the Japanese were at first rather wary of the newly arrived foreigners. The culture shock was quite strong, especially due to the fact that Europeans were not able to understand the Japanese writing system nor accustomed to using chopsticks.

They eat with their fingers instead of with chopsticks such as we use. They show their feelings without any self-control. They cannot understand the meaning of written characters. (from Boxer, Christian Century).

The Japanese were introduced to several new technologies and cultural practices (so were the Europeans to Japanese, see

Many foreigners were befriended by Japanese rulers, and their ability was sometimes recognized to the point of promoting one to the rank of

.European accounts of Japan

Renaissance Europeans were quite fond of Japan's immense richness in precious metals, mainly owing to Marco Polo's accounts of gilded temples and palaces, but also due to the relative abundance of surface ores characteristic of a volcanic country, before large-scale deep-mining became possible in Industrial times. Japan was to become a major exporter of copper and silver during the period.

Japan was also noted for its comparable or exceptional levels of population and urbanisation with the west (see List of countries by population in 1600), and at the time, some Europeans became quite fascinated with Japan, with Alessandro Valignano even writing that the Japanese "excel not only all the other Oriental peoples, they surpass the Europeans as well".[3]

Early European visitors noted the quality of Japanese craftsmanship and metalsmithing. This stems from the fact that Japan itself is rather poor in natural resources found commonly in Europe, especially iron. Thus, the Japanese were famously frugal with their consumable resources; what little they had they used with expert skill though because of this, they had not reached European levels.

Japanese military progress was also well noted. "A Spanish royal decree of 1609 specifically directed Spanish commanders in the Pacific 'not to risk the reputation of our arms and state against Japanese soldier.'" (Giving Up the Gun, Noel Perrin). Troops of Japanese samurai were later employed in the Maluku Islands in Southeast Asia by the Dutch to fight off the English.

Portuguese trade in the 16th century

Ever since 1514 that the Portuguese had traded with China from Malacca, and the year after the first Portuguese landfall in Japan, trade commenced between Malacca, China, and Japan. The Chinese Emperor had decreed an embargo against Japan as a result of piratical wokou raids against China - consequently, Chinese goods were in scarce supply in Japan and so, the Portuguese found a lucrative opportunity to act as middlemen between the two realms.[4]

Trade with Japan was initially open to any, but in 1550, the Portuguese Crown monopolized the rights to trade with Japan.[5] Henceforth, once a year a fidalgo was awarded the rights for a single trade venture to Japan with considerable privileges, such as the title of captain-major of the voyage to Japan, with authority over any Portuguese subjects in China or Japan while he was in port, and the right to sell his post, should he lack the necessary funds to undertake the enterprise. He could charter a royal vessel or purchase his own, at about 40,000 xerafins.[6] His ship would set sail from Goa, called at Malacca and China before proceeding to Japan and back.

In 1554, captain-major Leonel de Sousa

The state of civil-war in Japan was also highly beneficial to the Portuguese, as each competing lord sought to attract trade to their domains by offering better conditions.

The vessels

Among the vessels involved in the trade linking Goa and Japan, the most famous were Portuguese

The Portuguese referred to this vessel as the nau da prata ("silver carrack") or nau do trato ("trade carrack"); the Japanese dubbed them kurofune, meaning "

In the 16th century, large junks belonging to private owners from Macau often accompanied the great ship to Japan, about two or three; these could reach about 400 or 500 tons burden.

Traded items

By far the most valuable commodities exchanged in the "nanban trade" were Chinese silks for Japanese silver, which was then traded in China for more silk.[18] Although accurate statistics are lacking, it's been estimated that roughly half of Japan's yearly silver output was exported, most of it through the Portuguese, amounting to about 18 - 20 tons in silver bullion.[19] The English merchant Peter Mundy estimated that Portuguese investment at Canton ascended to 1,500,000 silver taels or 1,000,000 Spanish reales.[20] The Portuguese also exported surplus silk from Macau to Goa and Europe via Manila.[21] [22]

Nonetheless, numerous other items were also transactioned, such as gold, Chinese

Japanese (and Koreans) captured in battle were also sold by their compatriots to the Portuguese as slaves, but the Japanese would also sell family members they could not afford to sustain because of the civil-war. According to prof. Boxer, both old and modern Asian authors have "conveniently overlooked" their part in the enslavement of their countrymen.

The overall profits from the Japan trade, carried on through the black ship, was estimated to ascend to over 600,000 cruzados, according to various contemporary authors such as

After 1592, Portuguese trade was challenged by Japanese

Dutch trade

The

In 1605, two of the Liefde's crew were sent to

The Dutch also engaged in piracy and naval combat to weaken Portuguese and Spanish shipping in the Pacific, and ultimately became the only westerners to be allowed access to Japan from the small enclave of Dejima after 1638 and for the next two centuries.

Technological and cultural exchanges

Tanegashima guns

The Japanese were interested in Portuguese hand-held guns. The first two Europeans to reach Japan in the year 1543 were the Portuguese traders António da Mota and Francisco Zeimoto (Fernão Mendes Pinto claimed to have arrived on this ship as well, but this is in direct conflict with other data he presents), arriving on a Chinese ship at the southern island of Tanegashima where they introduced hand-held guns for trade. The Japanese were already familiar with gunpowder weaponry (invented by, and transmitted from China), and had been using basic Chinese originated guns and cannon tubes called "Teppō" (鉄砲 "Iron cannon") for around 270 years before the arrival of the Portuguese. In comparison, the Portuguese guns were light, had a matchlock firing mechanism, and were easy to aim. Because the Portuguese-made firearms were introduced into Tanegashima, the arquebus was ultimately called Tanegashima in Japan. At that time, Japan was in the middle of a civil war called the Sengoku period (Warring States period).

Within a year after the first trade in guns, Japanese swordsmiths and ironsmiths managed to reproduce the matchlock mechanism and mass-produce the Portuguese guns. Barely fifty years later, "by the end of the 16th century, guns were almost certainly more common in Japan than in any other country in the world", its armies equipped with a number of guns dwarfing any contemporary army in Europe (Perrin). The guns were strongly instrumental in the unification of Japan under

Red seal ships

European ships (galleons) were also quite influential in the Japanese shipbuilding industry and actually stimulated many Japanese ventures abroad.

The Shogunate established a system of commercial ventures on licensed ships called

By the beginning of the 17th century, the shogunate had built, usually with the help of foreign experts, several ships of purely Nanban design, such as the galleon

Catholicism in Japan

With the arrival of the leading

The first reaction from the

- "1. Japan is a country of the Gods, and for the padres to come hither and preach a devilish law, is a reprehensible and devilish thing ...

- 2. For the padres to come to Japan and convert people to their creed, destroying Shinto and Buddhist temples to this end, is a hitherto unseen and unheard-of thing ... to stir the canaille to commit outrages of this sort is something deserving of severe punishment." (From Boxer, The Christian Century in Japan)

Hideyoshi's reaction to Christianity proved stronger when the Spanish

The final blow came with

Other Nanban influences

The Nanban also had various other influences:

- Nanbandō (南蛮胴) designates a type of cuirass covering the trunk in one piece, a design imported from Europe.

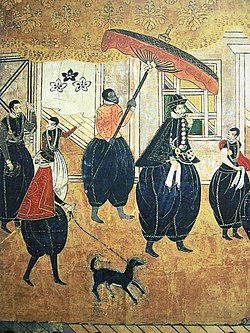

- Nanbanbijutsu (南蛮美術) generally describes Japanese art with Nanban themes or influenced by Nanban designs(See Nanban art).

- Nanbanga (南蛮画) designates the numerous pictorial representations that were made of the new foreigners and defines a whole style category in Japanese art (See )

- Nanbannuri (南蛮塗り) describes lacquers decorated in the Portuguese style, which were very popular items from the late 16th century (See example at: [3]).

- Nanbangashi ("(ビスケット), etc. These "Southern barbarian" sweets are on sale in many Japanese supermarkets today.

- Nanbanji or Nanbandera (Shunkoin temple in Kyoto.Shunkoin Temple

Decline of Nanban exchanges

After the country was pacified and unified by Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1603 however, Japan progressively closed itself to the outside world, mainly because of the rise of Christianity.

By 1650, except for the trade outpost of

The "barbarians" would come back 250 years later, strengthened by industrialization, and end Japan's isolation with the forcible opening of Japan to trade by an American military fleet under the command of

Usages of the word "Nanban"

The term Nanban have its origin from Four Barbarians in the Hua–Yi distinction in the 3rd century in China. Pronunciation of Chinese Character is Japanised, the 東夷 (Dōngyí) "Eastern Barbarians" called "Tōi" (it includes Japan itself), 南蛮 (Nánmán) "Southern Barbarians" called "Nanban", 西戎 (Xīróng) "Western Barbarians" called "Sei-Jū", and Běidí 北狄 "Northern Barbarians" called "Hoku-Teki".

Nanban just mean southeast asia in the Sengoku and Edo period. and it was going through the time, the word of "Nanban" mean turnd into the meaning "Western person" and "From Nanban" means "Exotic and Curious".

Strictly speaking "Nanban" means "Portuguese or Spanish" who were the most popular western foreigners in Japan, other western person sometimes called "紅毛人"(Kō-mōjin) "red-haired people" but Kō-mōjin was not as widespread as Nanban. In China, "紅毛" pronounce Ang mo and means a racial descriptor, and Japan decided to Westernize radically in order to better resist the West and essentially stopped considering the West as fundamentally uncivilized. Words like "Yōfu" (洋風 "western style") and "Ōbeifu" (欧米風 "European-American style)" replaced "Nanban" in most usages.

Still, the exact principle of westernization was Wakon-Yōsai (和魂洋才 "Japanese spirit Western talent"), implying that, although technology may be more advanced in the West, Japanese spirit is better than the West's. Hence though the West may be lacking, it has its strong points, which takes the affront out of calling it "barbarian."

Today the word "Nanban" is only used in a historical context, and is essentially felt as picturesque and affectionate. It can sometimes be used jokingly to refer to Western people or civilization in a cultured manner.

There is an area where Nanban is used exclusively to refer to a certain style and that is cooking and the names of dishes. Nanban dishes are not American or European, but an odd variety not using soy sauce or miso but rather curry powder and vinegar as their flavoring, a characteristic derived from Indo-Portuguese Goan cuisine. This is because when Portuguese and Spanish dishes were imported into Japan, dishes from Macau and other parts of China were imported as well.

Timeline

- 1543 – Portuguese sailors (among them possibly Fernão Mendes Pinto) arrive in Tanegashima and transmit the arquebus.

- 1549 – Francis Xavier arrives in Kagoshima.

- 1557 – Establishment of Macau by the Portuguese. Dispatch of annual trading ships to Japan.

- 1565 – Battle of Fukuda Bay, the first recorded naval clash between the Europeans and the Japanese

- 1570 – Japanese pirates occupy parts of Taiwan, from where they prey on China.

- 1571 – Daimyō Ōmura Sumitada assists the Portuguese in establishing the port of Nagasaki.

- 1575 – Battle of Nagashino, where firearms are used extensively.

- 1577 – First Japanese ships travel to Cochinchina, southern Vietnam.

- 1579 – The Jesuit Alessandro Valignanoarrives in Japan.

- 1580 – Ōmura Sumitada cedes Nagasaki "in perpetuity" to the Society of Jesus.

- 1580 – Franciscans from Japan escape to Vietnam.

- 1584 – Mancio Itō arrives in Lisbonwith three other Japanese, accompanied by a Jesuit father.

- 1588 – Hideyoshiprohibits piracy.

- 1592 – Japan invades Seven-Year Warwith an army of 160.000.

- - First known mention of Red Seal Ships.

- - First known mention of

- 1597 – Nagasaki.

- 1598 – Death of Hideyoshi.

- 1600 – Arrival of William Adamson the Liefde.

- - The Battle of Sekigahara unites Japan under Tokugawa Ieyasu.

- 1602 – Dutch warships attack the Portuguese carrack Santa Catarina near Portuguese Malacca.

- 1603 – Establishment of Bakufugovernment.

- - Establishment of the English Java.

- - Nippo Jisho Japanese to Portuguese dictionary is published by Jesuits in Nagasaki, containing entries for 32,293 Japanese words in Portuguese.

- - Establishment of the English

- 1605 – Two of William Adams's shipmates are sent to Pattani by Tokugawa Ieyasu, to invite Dutch trade to Japan.

- 1609 – The Dutch open a trading factory in Hirado.

- 1610 – Destruction of the Nossa Senhora da Graça near Nagasaki, leading to a 2-year hiatus in Portuguese trade

- 1612 – Siam.

- 1613 – England opens a trading factory in Hirado.

- - Hasekura Tsunenaga leaves for his embassy to the Americas and Europe. He returns in 1620.

- 1614 – Expulsion of the Jesuits from Japan. Prohibition of Christianity.

- 1615 – Japanese Jesuits start to proselytise in Vietnam.

- 1616 – Death of Tokugawa Ieyasu.

- 1622 – Mass martyrdom of Christians.

- - Death of Hasekura Tsunenaga.

- 1623 – The English close their factory at Hirado, because of unprofitability.

- - Siam to Japan, with an Ambassador of the Siamese king Songtham. He returns to Siam in 1626.

- - Prohibition of trade with the Spanish Philippines.

- -

- 1624 – Interruption of diplomatic relations with Spain.

- - Japanese Jesuits start to proselytise in Siam.

- 1628 – Destruction of Takagi Sakuemon's (高木作右衛門) Red Seal ship in Ayutthaya, Siam, by a Spanish fleet. Portuguese trade in Japan is prohibited for 3 years as a reprisal.

- 1632 – Death of Tokugawa Hidetada.

- 1634 – On orders of shōgun Iemitsu, the artificial island Dejima is built to constrain Portuguese merchants living in Nagasaki.

- 1637 – Shimabara Rebellion by Christian peasants.

- 1638 – Definitive prohibition of trade with Portugal as result of Shimabara Rebellion blamed on Catholic intrigues.

- 1641 – The Dutch trading factory is moved from Hirado to Dejima island.

Notes

- ^ Frequently referred to today in scholarship as kaikin, or "maritime restrictions", more accurately reflecting the booming trade that continued during this period and the fact that Japan was far from "closed" or "secluded."

- ISBN 978-0-87923-773-8

- ^ Valignano, 1584, Historia del Principio y Progreso de la Compañía de Jesús en las Indias Orientales.

- ^ BOXER: The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650, 1951, p. 91

- ^ BOXER: The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650, 1951, p. 91

- ^ BOXER: The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650, 1951, p. 303

- ^ BOXER: The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650, 1951, p. 92

- ^ BOXER: The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650, 1951, p. 98

- ^ BOXER: The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650, 1951, p. 101

- ^ BOXER: The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650, 1951, p. 101

- ^ C. R. Boxer, The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640 p.13

- ^ C. R. Boxer, Fidalgos on the Far-East 1550-1770, Oxford, 1968, p.14

- ^ C. R. Boxer, Fidalgos on the Far-East 1550-1770, Oxford, 1968, p.14

- ^ C. R. Boxer, Fidalgos on the Far-East 1550-1770, Oxford, 1968, p.15

- ^ C. R. Boxer, The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640 p.14

- ^ C. R. Boxer, The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640 p. 14

- ^ C. R. Boxer, The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640 p.14

- ^ C. R. Boxer, The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640 p.5

- ^ C. R. Boxer, The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640 p. 7

- ^ C. R. Boxer, The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640 p.6

- ^ C. R. Boxer, The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640 p.6

- ^ C. R. Boxer, The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640 p.7-8

- ^ C. R. Boxer, Fidalgos on the Far-East 1550-1770, Oxford, 1968, p.10

- ^ C. R. Boxer, Fidalgos on the Far-East 1550-1770, Oxford, 1968, p.15

- ^ C. R. Boxer, Fidalgos on the Far-East 1550-1770, Oxford, 1968, p.16

- ^ C. R. Boxer, Fidalgos on the Far-East 1550-1770, Oxford, 1968, p.223

- ISBN 0-19-517055-5. Retrieved 2014-02-02.)

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help - ISBN 0-19-533770-0. Retrieved 2014-02-02.)

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help - ^ Dias 2007, p. 71

- )

- ^ Monumenta Nipponica: Studies on Japanese Culture, Past and Present, Volume 59, Issues 3–4. Jōchi Daigaku. Sophia University. 2004. p. 463. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ISBN 1-135-78871-5. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- )

- ^ Monumenta Nipponica. Jōchi Daigaku. Sophia University. 2004. p. 465. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ISBN 0-231-51509-X. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ISBN 1-134-91843-7. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ C. R. Boxer, The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640 p.8

- ^ C. R. Boxer, The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640 p.169

- ^ C. R. Boxer, The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640 p.170

- ^ C. R. Boxer, The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640 p.170

- ^ BOXER: The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650, 1951, p. 301

- ^ C. R. Boxer, The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640 p.4

- ^ BOXER: The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650, 1951, p. 303

- ISBN 2-13-052893-7

- ISBN 1850292515

References

- Giving Up the Gun, Noel Perrin, David R. Godine Publisher, Boston. ISBN 0-87923-773-2

- Samurai, ISBN 0-8048-3287-0

- The Origins of Japanese Trade Supremacy. Development and Technology in Asia from 1540 to the Pacific War, Christopher Howe, The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-35485-7

- Yoshitomo Okamoto, The Namban Art of Japan, translated by Ronald K. Jones, Weatherhill/Heibonsha, New York & Tokyo, 1972

- José Yamashiro, Choque luso no Japão dos séculos XVI e XVII, Ibrasa, 1989

- Armando Martins Janeira, O impacto português sobre a civilização japonesa, Publicações Dom Quixote, Lisboa, 1970

- Wenceslau de Moraes, Relance da história do Japão, 2ª ed., Parceria A. M. Pereira Ltda, Lisboa, 1972

- Charles Ralph Boxer, The Christian Century in Japan (1951)

- They came to Japan, an anthology of European reports on Japan, 1543–1640, ed. by Michael Cooper, University of California press, 1995

- João Rodrigues's Account of Sixteenth-Century Japan, ed. by Michael Cooper, London: The Hakluyt Society, 2001 (ISBN 0-904180-73-5)

- Dias, Maria Suzette Fernandes (2007), Legacies of slavery: comparative perspectives, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, p. 238, ISBN 1-84718-111-2

- Charles Ralph Boxer, The Great Ship from Amacon - Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555-1640, Centro de Estudos Históricos Ultramarinos, 1963, Lisbon

- Charles Ralph Boxer, Fidalgos on the Far-East 1550-1770, Oxford University Press, 1968

External links

- The Christian Century in Japan, by Charles Boxer

- The Wakasa tale: an episode occurred when guns were introduced in Japan, F. A. B. Coutinho

- Nanban folding screens

- Nanban art (Japanese)

- Japanese Art and Western Influence

- Shunkoin Temple the Bell of Nanbanji

- Japan Mint: 2005 International Coin Design Competition, Jury's Special Award – "The Meeting of Cultures" by Vitor Santos (Portugal)