Vietnam

Socialist Republic of Viet Nam Cộng hòa Xã hội chủ nghĩa Việt Nam (Vietnamese) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Motto: Độc lập – Tự do – Hạnh phúc "Independence – Freedom – Happiness" | ||

| Anthem: Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist republic[5] | ||

| Nguyễn Phú Trọng | ||

| Võ Thị Ánh Xuân (acting) | ||

| Phạm Minh Chính | ||

| Vương Đình Huệ | ||

| Legislature | Declaration of Independence | 2 September 1945 |

| 21 July 1954 | ||

| 30 April 1975 | ||

| 2 July 1976 | ||

• Đổi Mới | 18 December 1986 | |

| 28 November 2013[b] | ||

| Area | ||

• Total | 331,344.82[7][c] km2 (127,932.95 sq mi) (66th) | |

• Water (%) | 6.38 | |

| Population | ||

• 2023 estimate | 100,300,000[10][11] (15th) | |

• 2019 census | 96,208,984[2] | |

• Density | 298/km2 (771.8/sq mi) (49th) | |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate | |

• Total | ||

• Per capita | ||

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate | |

• Total | ||

• Per capita | ||

| Gini (2018) | medium | |

| HDI (2022) | high (107th) | |

| Currency | Vietnamese đồng (₫) (VND) | |

| Time zone | UTC+07:00 (Vietnam Standard Time) | |

| Driving side | right | |

| Calling code | +84 | |

| ISO 3166 code | VN | |

| Internet TLD | .vn | |

Vietnam,[d][e] officially the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam (SRV),[f] is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about 331,000 square kilometres (128,000 sq mi) and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's fifteenth-most populous country. Vietnam shares land borders with China to the north, and Laos and Cambodia to the west. It shares maritime borders with Thailand through the Gulf of Thailand, and the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia through the South China Sea. Its capital is Hanoi and its largest city is Ho Chi Minh City (commonly referred to by its former name, Saigon).

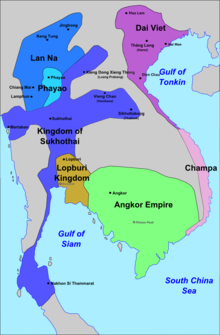

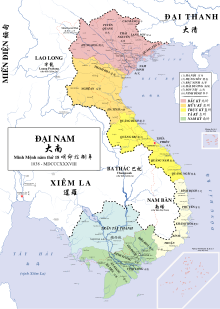

Vietnam was inhabited by the Paleolithic age, with states established in the first millennium BC on the Red River Delta in modern-day northern Vietnam. The Han dynasty annexed Northern and Central Vietnam under Chinese rule from 111 BC, until the first dynasty emerged in 939. Successive monarchical dynasties absorbed Chinese influences through Confucianism and Buddhism, and expanded southward to the Mekong Delta, conquering Champa. During most of the 17th and 18th centuries, Vietnam was effectively divided into two domains of Đàng Trong and Đàng Ngoài. The Nguyễn—the last imperial dynasty—surrendered to France in 1883. In 1887, its territory was integrated into French Indochina as three separate regions. In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the nationalist coalition Viet Minh, led by the communist revolutionary Ho Chi Minh, launched the August Revolution and declared Vietnam's independence in 1945.

Vietnam went through prolonged warfare in the 20th century. After

Vietnam is a developing country with a lower-middle-income economy. It has high levels of corruption, censorship, environmental issues and a poor human rights record; the country ranks among the lowest in international measurements of civil liberties, freedom of the press, and freedom of religion and ethnic minorities. It is part of international and intergovernmental institutions including the ASEAN, the APEC, the CPTPP, the Non-Aligned Movement, the OIF, and the WTO. It has assumed a seat on the United Nations Security Council twice.

Etymology

The name Việt Nam (Vietnamese pronunciation:

The form Việt Nam (

History

Prehistory and early history

Archaeological excavations have revealed the existence of humans in what is now Vietnam as early as the

By about 1,000 BC, the development of wet-

Dynastic Vietnam

According to Vietnamese legends,

In AD 938, the Vietnamese lord

From the 16th century onward, civil strife and frequent political infighting engulfed much of Dai Viet. First, the Chinese-supported

French Indochina

In the 1500s, the

Between 1615 and 1753,

Between 1862 and 1867, the southern third of the country became the

During the colonial period, guerrillas of the royalist

A nationalist political movement soon emerged, with leaders like

The French maintained full control of their colonies until World War II, when the

First Indochina War

In 1941, the

In July 1945, the Allies had decided to divide Indochina at the 16th parallel to allow Chiang Kai-shek of the Republic of China to receive the Japanese surrender in the north while Britain's Lord Louis Mountbatten received their surrender in the south. The Allies agreed that Indochina still belonged to France.[113][114]

But as the French were weakened by the

The colonial administration was thereby ended and French Indochina was dissolved under the Geneva Accords of 21 July 1954 into three countries—Vietnam, and the kingdoms of

Vietnam War

From 1953 to 1956, the

In 1963, Buddhist discontent with Diệm's Catholic regime erupted into

The communists attacked South Vietnamese targets during the 1968

Reunification and reforms

On 2 July 1976, North and South Vietnam were merged to form the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

At the

In 2021, General Secretary of the Communist Party, Nguyen Phu Trong, was re-elected for his third term in office, meaning he is Vietnam's most powerful leader in decades.[175]

Geography

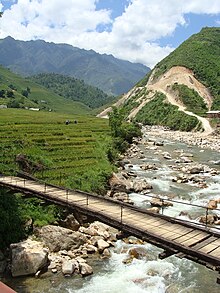

Vietnam is located on the eastern

Southern Vietnam is divided into coastal lowlands, the mountains of the

Climate

Due to differences in latitude and the marked variety in

Biodiversity

As the country is located within the

Vietnam is also home to 1,438 species of freshwater

In Vietnam, wildlife

The main environmental concern that persists in Vietnam today is the legacy of the use of the chemical

The Vietnamese government spends over

Apart from herbicide problems,

Government and politics

Vietnam is a

The general secretary of the CPV performs numerous key administrative functions, controlling the party's national organisation.[234] The prime minister is the head of government, presiding over a council of ministers composed of five deputy prime ministers and the heads of 26 ministries and commissions. Only political organisations affiliated with or endorsed by the CPV are permitted to contest elections in Vietnam. These include the Vietnamese Fatherland Front and worker and trade unionist parties.[234]

The

In 2023, a three-person collective leadership was responsible for governing Vietnam. President Võ Văn Thưởng,[240] Prime Minister Phạm Minh Chính (since 2021)[241] and the most powerful leader Nguyễn Phú Trọng (since 2011) as the Communist Party of Vietnam's General Secretary.[242] As of 2024, Vice President Võ Thị Ánh Xuân is the acting president of Vietnam after Võ Văn Thưởng resigned on the same year due to corruption charges against him.[243]

Foreign relations

Throughout its history, Vietnam's main foreign relationship has been with various Chinese dynasties.

Vietnam's current foreign policy is to consistently implement a policy of independence, self-reliance, peace, co-operation, and development, as well openness, diversification,

Military

The

Human rights and sociopolitical issues

Under the current constitution, the CPV is the only party allowed to rule, the operation of all other political parties being outlawed. Other human rights issues concern

Administrative divisions

Vietnam is divided into 58 provinces (Vietnamese: Tỉnh, chữ Hán: 省).[276] There are also five municipalities (thành phố trực thuộc trung ương), which are administratively on the same level as provinces.

|

|

Provinces are subdivided into provincial municipalities (thành phố trực thuộc tỉnh, 'city under province'), townships (thị xã) and counties (huyện), which are in turn subdivided into towns (thị trấn) or communes (xã).

Centrally controlled municipalities are subdivided into

Economy

| Share of world GDP (PPP)[12] | |

|---|---|

| Year | Share |

| 1980 | 0.21% |

| 1990 | 0.28% |

| 2000 | 0.39% |

| 2010 | 0.52% |

| 2020 | 0.80% |

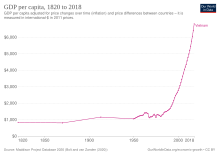

Throughout the history of Vietnam, its economy has been based largely on

In 1986, the

Deep

Based on findings by the

Agriculture

As a result of several

Seafood

The overall fisheries production of Vietnam from capture fisheries and aquaculture was 5.6 million MT in 2011 and 6.7 million MT in 2016. The output of Vietnam's fisheries sector has seen strong growth, which could be attributed to the continued expansion of the aquaculture sub-sector.[313]

Science and technology

In 2010, Vietnam's total state spending on science and technology amounted to roughly 0.45% of its GDP.

According to the

Tourism

Tourism is an important element of economic activity in the nation, contributing 7.5% of the total GDP. Vietnam hosted roughly 13 million tourists in 2017, an increase of 29.1% over the previous year, making it one of the fastest growing tourist destinations in the world. The vast majority of the tourists in the country, some 9.7 million, came from Asia; namely China (4 million), South Korea (2.6 million), and Japan (798,119).[327] Vietnam also attracts large numbers of visitors from Europe, with almost 1.9 million visitors in 2017; most European visitors came from Russia (574,164), followed by the United Kingdom (283,537), France (255,396), and Germany (199,872). Other significant international arrivals by nationality include the United States (614,117) and Australia (370,438).[327]

The most visited destinations in Vietnam are the largest city, Ho Chi Minh City, with over 5.8 million international arrivals, followed by Hanoi with 4.6 million and Hạ Long, including Hạ Long Bay with 4.4 million arrivals. All three are ranked in the top 100 most visited cities in the world.[328] Vietnam is home to eight UNESCO World Heritage Sites. In 2018, Travel + Leisure ranked Hội An as one of the world's top 15 best destinations to visit.[329]

Infrastructure

Transport

Much of Vietnam's modern transportation network can trace its roots to the French colonial era when it was used to facilitate the transportation of raw materials to its main ports. It was extensively expanded and modernised following the partition of Vietnam.[330] Vietnam's road system includes national roads administered at the central level, provincial roads managed at the provincial level, district roads managed at the district level, urban roads managed by cities and towns and commune roads managed at the commune level.[331] In 2010, Vietnam's road system had a total length of about 188,744 kilometres (117,280 mi) of which 93,535 kilometres (58,120 mi) are asphalt roads comprising national, provincial and district roads.[331] The length of the national road system is about 15,370 kilometres (9,550 mi) with 15,085 kilometres (9,373 mi) of its length paved. The provincial road system has around 27,976 kilometres (17,383 mi) of paved roads while 50,474 kilometres (31,363 mi) district roads are paved.[331]

Vietnam operates 20 major civil airports, including three international gateways:

Energy

Vietnam's energy sector is dominated largely by the state-controlled

Most of Vietnam's power is generated by either

The household gas sector in Vietnam is dominated by PetroVietnam, which controls nearly 70% of the country's domestic market for liquefied petroleum gas (LPG).[352] Since 2011, the company also operates five renewable energy power plants including the Nhơn Trạch 2 Thermal Power Plant (750 MW), Phú Quý Wind Power Plant (6 MW), Hủa Na Hydro-power Plant (180 MW), Dakdrinh Hydro-power Plant (125 MW) and Vũng Áng 1 Thermal Power Plant (1,200 MW).[353]

According to statistics from

Telecommunication

Telecommunications services in Vietnam are wholly provided by the Vietnam Post and Telecommunications General Corporation (now the

Water supply and sanitation

Vietnam has 2,360 rivers with an average annual discharge of 310 billion m³. The rainy season accounts for 70% of the year's discharge.[359] Most of the country's urban water supply systems have been developed without proper management within the last 10 years. Based on a 2008 survey by the Vietnam Water Supply and Sewerage Association (VWSA), existing water production capacity exceeded demand, but service coverage is still sparse. Most of the clean water supply infrastructure is not widely developed. It is only available to a small proportion of the population with about one third of 727 district towns having some form of piped water supply.[360] There is also concern over the safety of existing water resources for urban and rural water supply systems. Most industrial factories release their untreated wastewater directly into the water sources. Where the government does not take measures to address the issue, most domestic wastewater is discharged, untreated, back into the environment and pollutes the surface water.[360]

In recent years, there have been some efforts and collaboration between local and foreign universities to develop access to safe water in the country by introducing water filtration systems. There is a growing concern among local populations over the serious public health issues associated with water contamination caused by pollution as well as the high levels of arsenic in groundwater sources.[361] The government of Netherlands has been providing aid focusing its investments mainly on water-related sectors including water treatment projects.[362][363][364] Regarding sanitation, 78% of Vietnam's population has access to "improved" sanitation—94% of the urban population and 70% of the rural population. However, there are still about 21 million people in the country lacking access to "improved" sanitation according to a survey conducted in 2015.[365] In 2018, the construction ministry said the country's water supply, and drainage industry had been applying hi-tech methods and information technology (IT) to sanitation issues but faced problems like limited funding, climate change, and pollution.[366] The health ministry has also announced that water inspection units will be established nationwide beginning in June 2019. Inspections are to be conducted without notice, since there have been many cases involving health issues caused by poor or polluted water supplies as well unhygienic conditions reported every year.[367]

Health

By 2015, 97% of the population had access to improved water sources.

Since the early 2000s, Vietnam has made significant progress in combating

Education

Vietnam has an extensive state-controlled network of schools, colleges, and universities and a growing number of privately run and partially privatised institutions. General education in Vietnam is divided into five categories:

Demographics

As of 2021[update], the population of Vietnam stands at approximately 97.5 million people.

Since the partition of Vietnam, the population of the

Urbanisation

The number of people who live in urbanised areas in 2019 is 33,122,548 people (with the urbanisation rate at 34.4%).[2] Since 1986, Vietnam's urbanisation rates have surged rapidly after the Vietnamese government implemented the Đổi Mới economic program, changing the system into a socialist one and liberalising property rights. As a result, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City (the two major cities in the Red River Delta and Southeast regions respectively) increased their share of the total urban population from 8.5% and 24.9% to 15.9% and 31% respectively.[404] The Vietnamese government, through its construction ministry, forecasts the country will have a 45% urbanisation rate by 2020 although it was confirmed to only be 34.4% according to the 2019 census.[2] Urbanisation is said to have a positive correlation with economic growth. Any country with higher urbanisation rates has a higher GDP growth rate.[405] Furthermore, the urbanisation movement in Vietnam is mainly between the rural areas and the country's Southeast region. Ho Chi Minh City has received a large number of migrants due mainly to better weather and economic opportunities.[406]

A study also shows that rural-to-urban area migrants have a higher standard of living than both non-migrants in rural areas and non-migrants in urban areas. This results in changes to economic structures. In 1985, agriculture made up 37.2% of Vietnam's GDP; in 2008, that number had declined to 18.5%.[407] In 1985, industry made up only 26.2% of Vietnam's GDP; by 2008, that number had increased to 43.2%. Urbanisation also helps to improve basic services which increase people's standards of living. Access to electricity grew from 14% of total households with electricity in 1993 to above 96% in 2009.[407] In terms of access to fresh water, data from 65 utility companies shows that only 12% of households in the area covered by them had access to the water network in 2002; by 2007, more than 70% of the population was connected. Though urbanisation has many benefits, it has some drawbacks since it creates more traffic, and air and water pollution.[407]

Many Vietnamese use mopeds for transportation, since they are relatively cheap and easy to operate. Their large numbers have been known to cause traffic congestion and air pollution in Vietnam. In the capital city alone, the number of mopeds increased from 0.5 million in 2001 to 4.7 million in 2013.[407] With rapid development, factories have sprung up which indirectly pollute the air and water, for example in the 2016 Vietnam marine life disaster.[408] The government is intervening and attempting solutions to decrease air pollution by decreasing the number of motorcycles while increasing public transportation. It has introduced more regulations for waste handling. The amount of solid waste generated in urban areas of Vietnam has increased by more than 200% from 2003 to 2008. Industrial solid waste accounted for 181% of that increase. One of the government's efforts includes attempting to promote campaigns that encourage locals to sort household waste, since waste sorting is still not practised by most of Vietnamese society.[409]

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Hanoi |

1 | Ho Chi Minh City | Municipality | 8,993,082 | 11 | Tân Uyên | Bình Dương | 466,053 |  Haiphong  Cần Thơ |

| 2 | Hanoi | Municipality | 8,053,663 | 12 | Nha Trang | Khánh Hòa | 422,601 | ||

| 3 | Haiphong | Municipality | 2,028,514 | 13 | Dĩ An | Bình Dương | 403,760 | ||

| 4 | Cần Thơ | Municipality | 1,235,171 | 14 | Buôn Ma Thuột | Đắk Lắk | 375,590 | ||

| 5 | Da Nang | Municipality | 1,134,310 | 15 | Thanh Hóa | Thanh Hóa | 359,910 | ||

| 6 | Biên Hòa | Đồng Nai | 1,055,414 | 16 | Vũng Tàu | Bà Rịa-Vũng Tàu | 357,124 | ||

| 7 | Thủ Đức | Ho Chi Minh City | 1,013,795 | 17 | Bến Cát | Bình Dương | 355,663 | ||

| 8 | Huế | Thừa Thiên Huế | 652,572 | 18 | Thái Nguyên | Thái Nguyên | 340,403 | ||

| 9 | Thuận An | Bình Dương | 508,433 | 19 | Vinh | Nghệ An | 339,114 | ||

| 10 | Hải Dương | Hải Dương | 508,190 | 20 | Thủ Dầu Một | Bình Dương | 321,607 | ||

Religion

Religion in Vietnam (2019)[2]

Under Article 70 of the 1992 Constitution of Vietnam, all citizens enjoy freedom of belief and religion.[416] All religions are equal before the law and each place of worship is protected under Vietnamese state law. Religious beliefs cannot be misused to undermine state law and policies.[416][417] According to a 2007 survey 81% of Vietnamese people did not believe in a god.[418] Based on government findings in 2009, the number of religious people increased by 932,000.[419] The official statistics, presented by the Vietnamese government to the United Nations special rapporteur in 2014, indicate the overall number of followers of recognised religions is about 24 million of a total population of almost 90 million.[420] According to the General Statistics Office of Vietnam in 2019, Buddhists account for 4.79% of the total population, Catholics 6.1%, Protestants 1.0%, Hoahao Buddhists 1.02%, and Caodaism followers 0.58%.[2] Other religions includes Islam, Bahaʼís and Hinduism, representing less than 0.2% of the population.

The majority of Vietnamese do not follow any organised religion, though many of them observe some form of

Languages

The

The French language, a legacy of colonial rule, is spoken by many educated Vietnamese as a second language[citation needed], especially among the older generation and those educated in the former South Vietnam, where it was a principal language in administration, education and commerce. Vietnam remains a full member of the International Organisation of the Francophonie (La Francophonie) and education has revived some interest in the language.[432] Russian, and to a lesser extent German, Czech and Polish are known among some northern Vietnamese whose families had ties with the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War.[433] With improved relations with Western countries and recent reforms in Vietnamese administration, English has been increasingly used as a second language and the study of English is now obligatory in most schools either alongside or in place of French.[434][435] The popularity of Japanese, Korean, and Mandarin Chinese have also grown as the country's ties with other East Asian nations have strengthened.[436][437][438] Third-graders can choose one of seven languages (English, Russian, French, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, German) as their first foreign language.[439][440][441] In Vietnam's high school graduation examinations, students can take their foreign language exam in one of the above-mentioned languages.[442]

Culture

Vietnamese culture is considered part of

The traditional focuses of Vietnamese culture are based on humanity (nhân nghĩa) and harmony (hòa) in which family and community values are highly regarded.[448] Vietnam reveres a number of key cultural symbols,[452] such as the Vietnamese dragon which is derived from crocodile and snake imagery; Vietnam's national father, Lạc Long Quân is depicted as a holy dragon.[446][453][454] The lạc is a holy bird representing Vietnam's national mother Âu Cơ. Other prominent images that are also revered are the turtle, buffalo and horse.[455] Many Vietnamese also believe in the supernatural and spiritualism where illness can be brought on by a curse or sorcery or caused by non-observance of a religious ethic. Traditional medical practitioners, amulets and other forms of spiritual protection and religious practices may be employed to treat the ill person.[456] In the modern era, the cultural life of Vietnam has been deeply influenced by government-controlled media and cultural programs.[444] For many decades, foreign cultural influences, especially those of Western origin, were shunned. But since the recent reformation, Vietnam has seen a greater exposure to neighbouring Southeast Asian, East Asian as well to Western culture and media.[457]

The main Vietnamese formal dress, the

Literature

Vietnamese literature has centuries-deep history and the country has a rich tradition of

Music

Traditional Vietnamese music varies between the country's northern and southern regions.

Cuisine

Traditionally, Vietnamese cuisine is based around five fundamental taste "elements" (

Media

Vietnam's media sector is regulated by the government under the 2004 Law on Publication.[483] It is generally perceived that the country's media sector is controlled by the government and follows the official communist party line, though some newspapers are relatively outspoken.[484][485] The Voice of Vietnam (VOV) is the official state-run national radio broadcasting service, broadcasting internationally via shortwave using rented transmitters in other countries and providing broadcasts from its website, while Vietnam Television (VTV) is the national television broadcasting company. Since 1997, Vietnam has regulated public internet access extensively using both legal and technical means. The resulting lockdown is widely referred to as the "Bamboo Firewall".[486] The collaborative project OpenNet Initiative classifies Vietnam's level of online political censorship to be "pervasive",[487] while Reporters Without Borders (RWB) considers Vietnam to be one of 15 global "internet enemies".[488] Though the government of Vietnam maintains that such censorship is necessary to safeguard the country against obscene or sexually explicit content, many political and religious websites that are deemed to be undermining state authority are also blocked.[489]

Holidays and festivals

The country has eleven national recognised holidays. These include:

Sports

The

See also

Notes

- ^ The census data was also cited in the United States Department of State's 2022 Report on International Religious Freedom regarding Vietnam. However, the report indicated that this figure did not include the potentially significant number of individuals who engage in Buddhist practices to a certain extent without being formally participated in a Buddhist religious group.[3] An earlier United States Department of State report from 2019 revealed that 26.4 percent of the population identified with an organized religion. This breakdown included 14.9 percent identifying as Buddhist, 7.4 percent as Roman Catholic, 1.5 percent as Hoa Hao Buddhist, 1.2 percent as Cao Dai, and 1.1 percent as Protestant. The remainder did not identify with any religious group or observed beliefs such as animism or the reverence of ancestors, tutelary and protective saints, national heroes, or esteemed local figures.[4]

- ^ In effect since 1 January 2014.[6]

- ^ The area of Vietnam mentioned here is based on the land area statistics provided by the Vietnamese government. However, alternative figures exist. According to the CIA World Factbook, Vietnam's total area is 331,210 square kilometers,[8] while the BBC cites a slightly different measurement of 331,699 square kilometers.[9]

- ^ Vietnamese: Việt Nam [vîət nāːm] ⓘ

- ^ The spelling "Viet Nam" or the full Vietnamese form "Việt Nam" is sometimes used in English by local and government-operated media. "Viet Nam" is, in fact, formally designated and recognized by the Government of Vietnam, the United Nations and the International Organization for Standardization as the standardized country name. See also other spellings.

- ^ Alternatively the Socialist Republic of Vietnam with the different spelling

- ^ a b At first, Gia Long requested the name "Nam Việt", but the Jiaqing Emperor refused.[16][23]

- ^ Neither the American government nor Ngô Đình Diệm's State of Vietnam signed anything at the 1954 Geneva Conference. The non-communist Vietnamese delegation objected strenuously to any division of Vietnam; however, the French accepted the Việt Minh proposal[118] that Vietnam be united by elections under the supervision of "local commissions".[119] The United States, with the support of South Vietnam and the United Kingdom, countered with the "American Plan",[120] which provided for United Nations-supervised unification elections. The plan, however, was rejected by Soviet and other communist delegations.[121]

References

- ^ "Vietnam". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 18 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j General Statistics Office of Vietnam 2019.

- ^ 2022 Report on International Religious Freedom: Vietnam (Report). Office of International Religious Freedom, United States Department of State. 2022. Archived from the original on 11 February 2024. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ Vietnam Government Committee for Religious Affairs, 2018, cited in "2019 Report on International Religious Freedom: Vietnam". United States Department of State.

- ^ "Constitution of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam". FAOLEX Database. Food and Agriculture Organization.

The Constitution defines Vietnam as [having] a socialist rule of law, State of the people, by the people, and for the people. Vietnam is a unitary state ruled by [a] one-party system with coordination among State bodies in exercising legislative, executive and judicial rights.

- ^ Việt Nam News 2014.

- ^ Phê duyệt và công bố kết quả thống kê diện tích đất đai năm 2022 [Approval and announcement of land area statistics for 2022] (PDF) (Decision 3048/QĐ-BTNMT) (in Vietnamese). Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (Vietnam). 18 October 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Vietnam". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 17 January 2024. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ "Vietnam country profile". BBC News. 24 February 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Socio-economic situation in the fourth quarter and 2023 (Report). General Statistics Office of Vietnam. 29 December 2023. Archived from the original on 12 February 2024. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ An Chi (31 December 2023). "Dân số trung bình của Việt Nam năm 2023 đạt 100,3 triệu người" [Vietnam's Average Population Reaches 100.3 Million People in 2023]. Nhân Dân (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 12 February 2024. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024 Edition. (Vietnam)". www.imf.org. International Monetary Fund. 16 April 2024. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ World Bank 2018c.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/24" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. p. 289. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ a b Brindley, Erica Fox (2015). Ancient China and the Yue Perceptions and Identities on the Southern Frontier, c.400 BCE–50 CE. Cambridge University Press. p. 27.

The term "Yue" survives today in the name of the Vietnamese state (yue nan 越南, or, "Viet south" – "Viet of the South," – as the Vietnamese likely took it; or "South of the Viet" – as the Chinese likely took it

- ^ a b Woods 2002, p. 38.

- ^ a b c Norman & Mei 1976.

- ^ a b c d Meacham 1996.

- ^ Yue Hashimoto 1972, p. 1.

- ^ Knoblock & Riegel 2001, p. 510.

- ^ Lieberman 2003, p. 405.

- ^ Phan 1976, p. 510.

- ^ Shaofei & Guoqing 2016.

- ^ a b Ooi 2004, p. 932.

- ^ Tonnesson & Antlov 1996, p. 117.

- ^ Tonnesson & Antlov 1996, p. 126.

- S2CID 229297187.

- S2CID 243640447.

- ^ McKinney 2009.

- ^ Akazawa, Aoki & Kimura 1992, p. 321.

- ^ Rabett 2012, p. 109.

- ^ Dennell & Porr 2014, p. 41.

- ^ Matsumura et al. 2008, p. 12.

- ^ Matsumura et al. 2001.

- ^ Oxenham & Tayles 2006, p. 36.

- ^ Nguyen 1985, p. 16.

- ^ Karlström & Källén 2002, p. 83.

- ^ Oxenham & Buckley 2015, p. 329.

- ^ Tsang, Cheng-hwa (2000), "Recent advances in the Iron Age archaeology of Taiwan", Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, 20: 153–158, doi:10.7152/bippa.v20i0.11751

- ^ Turton, M. (2021). Notes from central Taiwan: Our brother to the south. Taiwan's relations with the Philippines date back millennia, so it's a mystery that it's not the jewel in the crown of the New Southbound Policy. Taiwan Times.

- ^ Everington, K. (2017). Birthplace of Austronesians is Taiwan, capital was Taitung: Scholar. Taiwan News.

- ^ Bellwood, P., H. Hung, H., Lizuka, Y. (2011). Taiwan Jade in the Philippines: 3,000 Years of Trade and Long-distance Interaction. Semantic Scholar.

- ^ a b Higham 1984.

- ^ a b Nang Chung & Giang Hai 2017, p. 31.

- ^ de Laet & Herrmann 1996, p. 408.

- ^ a b c Calò 2009, p. 51.

- ^ Kiernan 2017, p. 31.

- ^ Cooke, Li & Anderson 2011, p. 46.

- ^ Pelley 2002, p. 151.

- ^ Cottrell 2009, p. 14.

- ^ Đức Trần & Thư Hà 2000, p. 8.

- ^ Yao 2016, p. 62.

- ^ Holmgren 1980.

- ^ Taylor 1983, p. 30.

- ^ Pelley 2002, p. 177.

- ^ Cottrell 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Thái Nguyên & Mừng Nguyẽ̂n 1958, p. 33.

- ^ Chesneaux 1966, p. 20.

- ^ anon. 1972, p. 24.

- ^ Tuyet Tran & Reid 2006, p. 32.

- ^ Hiẻ̂n Lê 2003, p. 65.

- ^ Hong Lien & Sharrock 2014, p. 55.

- ^ a b Kiernan 2017, p. 226.

- ^ Cottrell 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Hong Lien & Sharrock 2014, p. 95.

- ^ Keyes 1995, p. 183.

- ^ Hong Lien & Sharrock 2014, p. 111.

- ^ Hong Lien & Sharrock 2014, p. 120.

- ^ Kiernan 2017, p. 265.

- ^ Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 158.

- ^ a b Vo 2011, p. 13.

- ^ Ooi & Anh Tuan 2015, p. 212.

- ^ a b Phuong Linh 2016, p. 39.

- ^ Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 174.

- ^ Leonard 1984, p. 131.

- ^ a b Ooi 2004, p. 356.

- ^ a b c Hoàng 2007, p. 50.

- ^ a b Tran 2018.

- ^ Hoàng 2007, p. 52.

- ^ Hoàng 2007, p. 53.

- ^ Li 1998, p. 89.

- ^ Lockard 2010, p. 479.

- ^ Tran 2017, p. 27.

- ^ McLeod 1991, p. 22.

- ^ Woods 2002, p. 42.

- ^ Cortada 1994, p. 29.

- ^ Mojarro, Jorge (10 March 2020). "The day the Filipinos conquered Saigon". The Manila Times.

- ^ Keith 2012, p. 46.

- ^ Keith 2012, pp. 49–50.

- ^ McLeod 1991, p. 61.

- ^ Ooi 2004, p. 520.

- ^ Cook 2001, p. 396.

- ^ Frankum 2011, p. 172.

- ^ Nhu Nguyen 2016, p. 37.

- ^ Richardson 1876, p. 269.

- ^ Keith 2012, p. 53.

- ^ Anh Ngo 2016, p. 71.

- ^ Quach Langlet 1991, p. 360.

- ^ Ramsay 2008, p. 171.

- ^ Zinoman 2000.

- ^ Lim 2014, p. 33.

- ^ Largo 2002, p. 112.

- ^ Khánh Huỳnh 1986, p. 98.

- ^ Odell & Castillo 2008, p. 82.

- ^ Thomas 2012.

- ^ Miller 1990, p. 293.

- ^ Gettleman et al. 1995, p. 4.

- ^ Thanh Niên 2015.

- ^ Vietnam Net 2015.

- ^ a b Joes 1992, p. 95.

- ^ a b c d e Pike 2011, p. 192.

- ^ Gunn 2014, p. 270.

- ^ Neville 2007, p. 175.

- ^ Smith 2007, p. 6.

- ^ Neville 2007, p. 124.

- ^ Tonnesson 2011, p. 66.

- ^ Waite 2012, p. 89.

- ^ Gravel 1971, p. 134.

- ^ Gravel 1971, p. 119.

- ^ Gravel 1971, p. 140.

- ^ Kort 2017, p. 96.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 43.

- ^ DK 2017, p. 39.

- ^ a b c van Dijk et al. 2013, p. 68.

- ^ Guttman, John (25 July 2013). "Why did Sweden support the Viet Cong?". History Net. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ Moïse 2017, p. 56.

- ^ Vu 2007.

- ^ Turner 1975, p. 143.

- ^ Heneghan 1969, p. 160.

- ^ Turner 1975, p. 177.

- ^ Crozier 1955.

- ^ Turner 1975, pp. 174–178.

- ^ Gilbert 2013, p. 292.

- ^ a b Jukes 1973, p. 209.

- ^ a b Olsen 2007, p. 92.

- ^ Khoo 2011, p. 27.

- ^ Muehlenbeck & Muehlenbeck 2012, p. 221.

- ^ Willbanks 2013, p. 53.

- ^ Duy Hinh & Dinh Tho 2015, p. 238.

- ^ Isserman & Bowman 2009, p. 46.

- ^ Alterman 2005, p. 213.

- ^ Lewy 1980.

- ^ Gibbons 2014, p. 166.

- ^ Li 2012, p. 67.

- ^ Gillet 2011.

- ^ Dallek 2018.

- ^ Turner 1975, p. 251.

- ^ Frankum 2011, p. 209.

- ^ Eggleston 2014, p. 1.

- ^ History 2018.

- ^ Tucker 2011, p. 749.

- ^ Brigham 1998, p. 86.

- ^ The New York Times 1976.

- ^ Hirschman, Preston & Manh Loi 1995.

- ^ Shenon 1995.

- ^ Obermeyer, Murray & Gakidou 2008.

- ^ Dohrenwend et al. 2018, p. 69.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ Elliott 2010, pp. 499, 512–513.

- ^ Sagan & Denny 1982.

- ^ Spokesman-Review 1977, p. 8.

- ^ Moise 1988, p. 12.

- ^ Kissi 2006, p. 144.

- ^ Meggle 2004, p. 166.

- ^ Hampson 1996, p. 175.

- ^ Khoo 2011, p. 131.

- ^ a b BBC News 1997.

- ^ Văn Phúc 2014.

- ^ Murray 1997, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b c Bich Loan 2007.

- ^ Howe 2016, p. 20.

- ^ Goodkind 1995.

- ^ Gallup 2002.

- ^ a b Wagstaff, van Doorslaer & Watanabe 2003.

- ^ "Vietnam's ruling Communist Party re-elects chief Trong for rare third term". France 24. 31 January 2021.

- ^ "Vietnam". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 17 January 2024. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ "Vietnam country profile". BBC News. 24 February 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Nasuchon 2008, p. 7.

- ^ Protected Areas and Development Partnership 2003, p. 13.

- ^ Fröhlich et al. 2013, p. 5.

- ^ Natural Resources and Environment Program 1995, p. 56.

- ^ AgroViet Newsletter 2007.

- ^ Huu Chiem 1993, p. 180.

- ^ Minh Hoang et al. 2016.

- ^ Huu Chiem 1993, p. 183.

- ^ Hong Truong, Ye & Stive 2017, p. 757.

- ^ Vietnamese Waters Zone.

- ^ Cosslett & Cosslett 2017, p. 13.

- ^ Van De et al. 2008.

- ^ Hong Phuong 2012, p. 3.

- ^ Việt Nam News 2016.

- ^ Vietnam National Administration of Tourism 2014.

- ^ Boobbyer & Spooner 2013, p. 173.

- ^ Cosslett & Cosslett 2013, p. 13.

- ^ Anh 2016a.

- ^ The Telegraph.

- ^ Vu 1979, p. 66.

- ^ Riehl & Augstein 1973, p. 1.

- ^ a b Buleen 2017.

- ^ Vietnam Net 2018a.

- ^ "Vietnamese amazed at snow-capped northern mountains". VnExpress. 11 January 2021.

- ^ a b Thi Anh.

- ^ Overland 2017.

- ^ "Report: Flooded Future: Global vulnerability to sea level rise worse than previously understood". climatecentral.org. 29 October 2019. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage Convention 1994.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage Convention 2003.

- ^ Pha Le 2016.

- ^ BirdLife International 2016.

- ^ Kinver 2011.

- ^ a b Dall 2017.

- ^ Dang Vu & Nielsen 2018.

- ^ Nam Dang & Nielsen 2019.

- ^ Banout et al. 2014.

- ^ a b Cerre 2016.

- ^ Brown 2018.

- ^ Agence France-Presse 2016.

- ^ MacLeod 2012.

- ^ United States Agency for International Development.

- ^ Stewart 2018.

- ^ Việt Nam News 2018a.

- ^ Nikkei Asian Review 2018.

- ^ NHK World-Japan 2018.

- ^ Agent Orange Record.

- PMID 33293507.

- ^ Berg et al. 2007.

- ^ Merola et al. 2014.

- ^ Miguel & Roland 2005.

- ^ Government of the United Kingdom 2017.

- ^ LM Report 2000.

- ^ United Nations Development Programme 2018.

- ^ United States Department of State 2006.

- ^ Van Thanh 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Government of Vietnam (II).

- ^ Greenfield 1994, p. 204.

- ^ Baccini, Impullitti & Malesky 2017.

- ^ The Economist 2008.

- ^ Embassy of Vietnam in USA.

- ^ Ministry of Justice 1999.

- ^ "Vietnam parliament elects new president Vo Van Thuong". www.aljazeera.com.

- ^ "Vietnam picks new PM and president for next 5 years". Nikkei Asia.

- ^ "New president of Vietnam nominated by Communist Party: Report". www.aljazeera.com.

- ^ "Vietnam's vice president becomes interim president". apnews.com.

- ^ a b c Thayer 1994.

- ^ Thanh Hai 2016, p. 177.

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2018.

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2013.

- ^ a b Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2007.

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2014.

- ^ Dayley 2018, p. 98.

- ^ Mitchell 1995.

- ^ Green 2012.

- ^ Smith 2005, p. 386.

- ^ "Clinton Makes Historic Visit to Vietnam". abcnews.com.

- ^ Institute of Regional Studies 2001, p. 66.

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- ^ Garamone 2016.

- ^ Hutt 2020.

- ^ Corr 2019.

- ^ Tran 2020.

- ^ Taylor & Rutherford 2011, p. 50.

- ^ Yan 2016.

- ^ a b Voice of Vietnam 2016.

- ^ The Economic Times 2018.

- ^ The Japan Times 2015.

- ^ Voice of Vietnam 2018b.

- ^ Ministry of Defence Russia 2018.

- ^ The Telegraph 2012.

- ^ United Nations Treaty Collection.

- ^ Giap 2017.

- ^ a b BBC News 2009.

- ^ Mydans 2009.

- ^ "VIET NAM – UN ACT". UN-Act.

- ^ "Women, children and babies: human trafficking to China is on the rise". Asia News. 11 July 2019.

- ^ "Vietnam's Human Trafficking Problem Is Too Big to Ignore". The Diplomat. 8 November 2019.

- ^ Japan Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism.

- ^ Cornell University.

- ^ Kim Phuong 2014, p. 1.

- ^ Kimura 1986.

- ^ Adhikari, Kirkpatrick & Weiss 1992, p. 249.

- ^ Ngoc Vo & Le 2014, p. 7.

- ^ Van Tho 2003, p. 11.

- ^ Litvack, Litvack & Rondinelli 1999, p. 31.

- ^ Freeman 2002.

- ^ Litvack, Litvack & Rondinelli 1999, p. 33.

- ^ a b Van Tho 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Hoang Vuong & Dung Tran 2009.

- ^ Hoang Vuong 2014.

- ^ Largo 2002, p. 66.

- ^ International Monetary Fund 1999, p. 23.

- ^ Cockburn 1994.

- ^ Pincus 2015, p. 27; this article refers to the so-called "Vent for surplus" theory of international trade.

- ^ Quang Vinh, p. 13.

- ^ "WTO | Accessions: Viet Nam". www.wto.org.

- ^ Asian Development Bank 2010, p. 388.

- ^ Thanh Niên 2010.

- ^ Vierra & Vierra 2011, p. 5.

- ^ a b Vandemoortele & Bird 2010.

- ^ a b Cuong Le et al. 2010, p. 23.

- ^ H. Dang & Glewwe 2017, p. 9.

- ^ Vandemoortele 2010.

- ^ UPI.com 2013.

- ^ Fong-Sam 2010, p. 26.

- ^ Việt Nam News 2018b.

- ^ Vietnam News Agency 2018.

- ^ Tuổi Trẻ News 2012.

- ^ Vietnam Net 2016a.

- ^ Mai 2017.

- ^ Voice of Vietnam 2018c.

- ^ Nielsen 2007, p. 1.

- ^ Summers 2014.

- ^ Truong, Vo & Nguyen 2018, p. 172.

- ^ "Fisheries Country Profile: Vietnam". Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center. June 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ a b DigInfo 2007.

- ^ a b Borel 2010.

- ^ Việt Nam News 2010.

- ^ Koblitz 2009, p. 198.

- ^ CNRS 2010.

- ^ Koppes 2010.

- ^ Vietnam National Space Centre 2016.

- ^ Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology 2017.

- ^ Raslan 2017.

- ^ UNESCO Media Services 2016.

- . Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ "Global Innovation Index". INSEAD Knowledge. 28 October 2013. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ a b UNESCO Publishing, pp. 713–714.

- ^ a b Vietnam National Administration of Tourism 2018.

- ^ Quy 2018.

- ^ Terzian 2018.

- ^ Crook 2014, p. 7.

- ^ a b c General Statistics Office of Vietnam 2010.

- ^ Huu Duc et al. 2013, p. 2080.

- ^ General Statistics Office of Vietnam 2011.

- ^ Linh Le & Anh Trinh 2016.

- ^ Sohr et al. 2016, p. 220.

- ^ a b Chin 2018.

- ^ The Japan Times 2009.

- ^ Vietnam+ 2008.

- ^ The New York Times 2018.

- ^ a b Vietnam Net 2018b.

- ^ South East Asia Iron and Steel Institute 2009.

- ^ Chi 2017.

- ^ Tatarski 2017.

- ^ Hoang 2016, p. 1.

- ^ Vietnam Investment Review 2018.

- ^ Ha, Giang & Denslow 2012.

- ^ Index Mundi 2018.

- ^ Intellasia 2010.

- ^ Electricity of Vietnam 2017, p. 10.

- ^ a b Electricity of Vietnam 2017, p. 12.

- ^ Nguyen et al. 2016.

- ^ Nikkei Asian Review.

- ^ Viet Trung, Quoc Viet & Van Chat 2016, p. 70.

- ^ Viet Trung, Quoc Viet & Van Chat 2016, p. 64.

- ^ a b Pham 2015, p. 6.

- ^ Pham 2015, p. 7.

- ^ Việt Nam News 2012.

- ^ Oxford Business Group 2017.

- ^ British Business Group Vietnam 2017, p. 1.

- ^ a b British Business Group Vietnam 2017, p. 2.

- ^ University of Technology Sydney 2018.

- ^ Government of the Netherlands 2016.

- ^ Government of the Netherlands 2018.

- ^ Anh 2018.

- ^ UNICEF 2015.

- ^ Việt Nam News 2018c.

- ^ Việt Nam News 2018d.

- ^ Index Mundi 2016.

- ^ World Bank 2016a.

- ^ World Bank 2016b.

- ^ World Bank 2017.

- ^ The Harvard Crimson 1972.

- ^ Trung Chien 2006, p. 65.

- ^ BBC News 2005.

- ^ Haberman 2014.

- ^ Gustafsson 2010, p. 125.

- ^ Van Nam et al. 2005.

- ^ Trinh et al. 2016.

- ^ a b McNeil 2016.

- ^ Lieberman & Wagstaff 2009, p. 40.

- ^ Manyin 2005, p. 4.

- ^ Vietnam Women's Union 2005.

- ^ World Bank 2018a.

- ^ BBC News 2018.

- ^ UNICEF.

- ^ Ha Trân 2014.

- ^ World Bank 2013.

- ^ World Bank 2015.

- ^ Pham 2012.

- ^ Chapman & Liu 2013.

- ^ de Mora & Wood 2014, p. 55.

- ^ Vietnam Net 2016b.

- ^ a b c Jones 1998, p. 21.

- ^ United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

- ^ Fraser 1980.

- ^ Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration 2013, p. 1.

- ^ Government of Vietnam (I).

- ^ Cultural Orientation Resource Centre, p. 7.

- ^ Montagnard Human Rights Organisation.

- ^ Koskoff 2008, p. 1316.

- ^ Dodd & Lewis 2003, p. 531.

- ^ Amer 1996.

- ^ Feinberg 2016.

- ^ United Nations Population Fund 2009, p. 117.

- ^ World Bank 2002.

- ^ United Nations Population Fund 2009, p. 102.

- ^ a b c d Cira et al. 2011, p. 194.

- ^ Tiezzi 2016.

- ^ Trương 2018, p. 19.

- ISBN 978-604-75-1532-5. Archived from the original(PDF) on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ "Nghị quyết số 1111/NQ-UBTVQH14 năm 2020 về việc sắp xếp các đơn vị hành chính cấp huyện, cấp xã và thành lập thành phố Thủ Đức thuộc Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh". 9 December 2020. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ "Nghị quyết số 1264/NQ-UBTVQH14 năm 2021 về việc điều chỉnh địa giới hành chính các đơn vị hành chính cấp huyện và sắp xếp, thành lập các phường thuộc thành phố Huế, tỉnh Thừa Thiên Huế". 27 April 2021. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Nghị quyết số 857/NQ-UBTVQH14 năm 2020 về việc thành lập thành phố Dĩ An, thành phố Thuận An và các phường thuộc thị xã Tân Uyên, tỉnh Bình Dương". 10 January 2020. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ "Nghị quyết số 788/NQ-UBTVQH14 năm 2019 về việc sắp xếp các đơn vị hành chính cấp huyện, cấp xã thuộc tỉnh Hải Dương". 16 October 2019. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ "Nghị quyết số 837/NQ-UBTVQH14 năm 2019 về việc sắp xếp các đơn vị hành chính cấp huyện, cấp xã thuộc tỉnh Quảng Ninh". 17 December 2019. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ a b Ministry of Justice 1992.

- ^ Ministry of Justice 2004b.

- ^ Zuckerman 2007, p. 11.

- ^ General Statistics Office of Vietnam 2009.

- ^ Bielefeldt 2014.

- ^ Woods 2002, p. 34.

- ^ Keith 2012, pp. 42, 72.

- ^ Lamport 2018, p. 898.

- ^ Largo 2002, p. 168.

- ^ a b c Van Hoang 2017, p. 1.

- ^ Cultural Orientation Resource Centre, pp. 5, 7.

- ^ United States Department of State 2005.

- ^ Kỳ Phương & Lockhart 2011, p. 35.

- ^ Levinson & Christensen 2002, p. 89.

- ^ Sharma 2009, p. 48.

- ^ Cultural Orientation Resource Centre, p. 10.

- ^ French Senate 1997.

- ^ Van Van, p. 8.

- ^ Van Van, p. 9.

- ^ Government of the United Kingdom 2018.

- ^ Wai-ming 2002, p. 3.

- ^ Anh Dinh 2016, p. 63.

- ^ Hirano 2016.

- ^ Thống Nhất. "Nhà trường chọn 1 trong 7 thứ tiếng làm ngoại ngữ 1". Hànộimới. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Nguyễn, Tuệ (8 March 2021). "Vì sao tiếng Hàn, tiếng Đức là ngoại ngữ 1 trong trường phổ thông?". Thanh Niên. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Ngọc Diệp (4 March 2021). "Tiếng Hàn, tiếng Đức được đưa vào chương trình phổ thông, học sinh được tự chọn". Tuổi Trẻ. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Phạm, Mai (20 April 2022). "Các trường hợp được miễn thi ngoại ngữ kỳ thi tốt nghiệp THPT 2022" [Exemption from the foreign language test in the high school graduation exam]. VietnamPlus. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Tung Hieu 2015, p. 71.

- ^ a b c Nhu Nguyen 2016, p. 32.

- ^ Endres 2001.

- ^ a b Grigoreva 2014, p. 4.

- ^ UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage 2012.

- ^ a b Zhu et al. 2017, p. 142.

- ^ a b McLeod & Thi Dieu 2001, p. 8.

- ^ Momoki 1996, p. 36.

- ^ Kỳ Phương & Lockhart 2011, p. 84.

- ^ Vo 2012, p. 96.

- ^ Gallop 2017.

- ^ Vietnamese-American Association.

- ^ Chonchirdsin 2016.

- ^ Waitemata District Health Board 2015, p. 2.

- ^ Phuong 2012.

- ^ Lewandowski 2011, p. 12.

- ^ a b Howard 2016, p. 90.

- ^ Chico 2013, p. 354.

- ^ Pha Le 2014.

- ^ Vietnam Net 2017a.

- ^ Huong 2010.

- ^ Norton 2015.

- ^ Le 2008.

- ^ Vo 2012, p. 4.

- ^ Tran & Le 2017, p. 5.

- ^ Trần 1972.

- ^ Miettinen 1992, p. 163.

- ^ Trần 1985.

- ^ Voice of Vietnam 2018d.

- ^ Duy 2016.

- ^ Phương 2018.

- ^ Chen 2018, p. 194.

- ^ Vietnam Culture Information Network 2014.

- ^ Special Broadcasting Service 2013.

- ^ Corapi 2010.

- ^ Clark & Miller 2017.

- ^ Nguyen 2011.

- ^ Thaker & Barton 2012, p. 170.

- ^ Williams 2017.

- ^ Batruny 2014.

- ^ Ministry of Justice 2004a.

- ^ Xuan Dinh 2000.

- ^ Datta & Mendizabal 2018.

- ^ Wilkey 2002.

- ^ OpenNet Initiative 2012.

- ^ Reporters Without Borders.

- ^ Berkman Klein Center 2006.

- ^ Ministry of Justice 2012.

- ^ Travel 2017, p. 37.

- ^ Loan 2018.

- ^ Anh 2016b.

- ^ Trieu Dan 2017, p. 92.

- ^ Pike 2018.

- ^ Travel 2017, p. 34.

- ^ Englar 2006, p. 23.

- ^ Anderson & Lee 2005, p. 217.

- ^ Green 2001, p. 548.

- ^ Nghia & Luan 2017.

- ^ FourFourTwo 2017.

- ^ China Daily 2008.

- ^ The Saigon Times Daily 2018.

- ^ Gomes 2019.

- ^ Rick 2018.

- ^ Yan, Jun & Long 2018.

- ^ International Olympic Committee 2018.

- ^ Sims 2016.

- ^ Vietnam basketball Vietnam Online. Accessed 19 February 2020.

Sources

- Dror, Olga (2018). Making Two Vietnams: War and Youth Identities, 1965–1975. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-47012-4.

- ISBN 978-0-465-09436-3.

- Holcombe, Alec (2020). Mass Mobilization in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, 1945–1960. University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-8447-5.

- Nguyen, Lien-Hang T. (2012). Hanoi's War: An International History of the War for Peace in Vietnam. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3551-7.

- Vu, Tuong; Fear, Sean, eds. (2020). The Republic of Vietnam, 1955–1975: Vietnamese Perspectives on Nation Building. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-4513-3.

- Richardson, John (1876). A school manual of modern geography. Physical and political. Publisher not identified.

- Thái Nguyên, Văn; Mừng Nguyẽ̂n, Văn (1958). A Short History of Viet-Nam. Vietnamese-American Association.

- Chesneaux, Jean (1966). The Vietnamese Nations: Contribution to a History. Current Book Distributors.

- Heneghan, George Martin (1969). Nationalism, Communism and the National Liberation Front of Vietnam: Dilemma for American Foreign Policy. Department of Political Science, Stanford University.

- Gravel, Mike (1971). The Pentagon Papers: The Defense Department History of United States Decision-making on Vietnam. ISBN 978-0-8070-0526-2.

- Peasant and Labour. 1972.

- Yue Hashimoto, Oi-kan (1972). Phonology of Cantonese. ISBN 978-0-521-08442-0.

- Jukes, Geoffrey (1973). The Soviet Union in Asia. ISBN 978-0-520-02393-2.

- Turner, Robert F. (1975). Vietnamese communism, its origins and development. ISBN 978-0-8179-6431-3.

- Phan, Khoang (1976). Việt sử: xứ đàng trong, 1558–1777. Cuộc nam-tié̂n của dân-tộc Việt-Nam. Nhà Sách Khai Trí (in Vietnamese). Xuân thu.

- Vu, Tu Lap (1979). Vietnam: Geographical Data. Foreign Languages Publishing House.

- Lewy, Guenter (1980). America in Vietnam. ISBN 978-0-19-991352-7.

- Holmgren, Jennifer (1980). Chinese colonisation of northern Vietnam: administrative geography and political development in the Tongking Delta, first to sixth centuries A.D. Australian National University, Faculty of Asian Studies: distributed by Australian University Press. ISBN 978-0-909879-12-9.

- Taylor, Keith Weller (1983). The Birth of Vietnam. ISBN 978-0-520-04428-9.

- Leonard, Jane Kate (1984). Wei Yuan and China's Rediscovery of the Maritime World. ISBN 978-0-674-94855-6.

- ISBN 978-0-896-80119-6.

- Khánh Huỳnh, Kim (1986). Vietnamese Communism, 1925–1945. ISBN 978-0-8014-9397-3.

- Miller, Robert Hopkins (1990). United States and Vietnam 1787–1941. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7881-0810-5.

- McLeod, Mark W. (1991). The Vietnamese Response to French Intervention, 1862–1874. ISBN 978-0-275-93562-7.

- Joes, Anthony James (1992). Modern Guerrilla Insurgency. ISBN 978-0-275-94263-2.

- Miettinen, Jukka O. (1992). Classical Dance and Theatre in South-East Asia. ISBN 978-0-19-588595-8.

- Adhikari, Ramesh; Kirkpatrick, Colin H.; Weiss, John (1992). Industrial and Trade Policy Reform in Developing Countries. ISBN 978-0-7190-3553-1.

- Akazawa, Takeru; Aoki, Kenichi; Kimura, Tasuku (1992). The evolution and dispersal of modern humans in Asia. ISBN 978-4-938424-41-1.

- Cortada, James W. (1994). Spain in the Nineteenth-century World: Essays on Spanish Diplomacy, 1789–1898. ISBN 978-0-313-27655-2.

- Keyes, Charles F. (1995). The Golden Peninsula: Culture and Adaptation in Mainland Southeast Asia. ISBN 978-0-8248-1696-4.

- Gettleman, Marvin E.; Franklin, Jane; Young, Marilyn B.; Franklin, H. Bruce (1995). Vietnam and America: A Documented History. ISBN 978-0-8021-3362-5.

- Proceedings of the Regional Dialogue on Biodiversity and Natural Resources Management in Mainland Southeast Asian Economies, Kunming Institute of Botany, Yunnan, China, 21–24 February 1995. Natural Resources and Environment Program, Thailand Development Research Institute Foundation. 1995.

- Hampson, Fen Osler (1996). Nurturing Peace: Why Peace Settlements Succeed Or Fail. ISBN 978-1-878379-55-9.

- de Laet, Sigfried J.; Herrmann, Joachim (1996). History of Humanity: From the seventh century B.C. to the seventh century A.D. ISBN 978-92-3-102812-0.

- Tonnesson, Stein; Antlov, Hans (1996). Asian Forms of the Nation. ISBN 978-0-7007-0442-2.

- Murray, Geoffrey (1997). Vietnam Dawn of a New Market. ISBN 978-0-312-17392-0.

- Jones, John R. (1998). Guide to Vietnam. Bradt Publications. ISBN 978-1-898323-67-9.

- Brigham, Robert Kendall (1998). Guerrilla Diplomacy: The NLF's Foreign Relations and the Viet Nam War. ISBN 978-0-8014-3317-7.

- Li, Tana (1998). Nguyễn Cochinchina: Southern Vietnam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. ISBN 978-0-87727-722-4.

- Vietnam: Selected Issues. ISBN 978-1-4519-8721-8.

- Litvack, Jennie; Litvack, Jennie Ilene; Rondinelli, Dennis A. (1999). Market Reform in Vietnam: Building Institutions for Development. ISBN 978-1-56720-288-5.

- Đức Trần, Hồng; Thư Hà, Anh (2000). A Brief Chronology of Vietnam's History. Thế Giới Publishers.

- Cook, Bernard A. (2001). Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia. ISBN 978-0-8153-4057-7.

- Knoblock, John; Riegel, Jeffrey (2001). The Annals of Lü Buwei. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3354-0.

- Selections from Regional Press. Vol. 20. Institute of Regional Studies. 2001.

- Green, Thomas A. (2001). Martial Arts of the World: A-Q. ISBN 978-1-57607-150-2.

- Karlström, Anna; Källén, Anna (2002). Southeast Asian Archaeology. Östasiatiska Samlingarna (Stockholm, Sweden), European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists. International Conference. ISBN 978-91-970616-0-5.

- Levinson, David; Christensen, Karen (2002). Encyclopedia of Modern Asia. ISBN 978-0-684-31247-7.

- Pelley, Patricia M. (2002). Postcolonial Vietnam: New Histories of the National Past. ISBN 978-0-8223-2966-4.

- Woods, L. Shelton (2002). Vietnam: a global studies handbook. ISBN 978-1-57607-416-9.

- Largo, V. (2002). Vietnam: Current Issues and Historical Background. ISBN 978-1-59033-368-6.

- Page, Melvin Eugene; Sonnenburg, Penny M. (2003). Colonialism: An International, Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia. ISBN 978-1-57607-335-3.

- Dodd, Jan; Lewis, Mark (2003). Vietnam. ISBN 978-1-84353-095-4.

- Hiẻ̂n Lê, Năng (2003). Three victories on the Bach Dang river. Nhà xuất bản Văn hóa-thông tin.

- Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Integration of the Mainland Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–1830, Vol 1. Cambridge University Press.

- Protected Areas and Development Partnership (2003). Review of Protected Areas and Development in the Four Countries of the Lower Mekong River Region. ICEM. ISBN 978-0-9750332-4-1.

- Meggle, Georg (2004). Ethics of Humanitarian Interventions. ISBN 978-3-11-032773-1.

- Ooi, Keat Gin (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2.

- Smith, Anthony L. (2005). Southeast Asia and New Zealand: A History of Regional and Bilateral Relations. ISBN 978-0-86473-519-5.

- Alterman, Eric (2005). When Presidents Lie: A History of Official Deception and Its Consequences. ISBN 978-0-14-303604-3.

- Anderson, Wanni Wibulswasdi; Lee, Robert G. (2005). Displacements and Diasporas: Asians in the Americas. ISBN 978-0-8135-3611-8.

- Kissi, Edward (2006). Revolution and Genocide in Ethiopia and Cambodia. ISBN 978-0-7391-1263-2.

- Oxenham, Marc; Tayles, Nancy (2006). Bioarchaeology of Southeast Asia. ISBN 978-0-521-82580-1.

- Englar, Mary (2006). Vietnam: A Question and Answer Book. ISBN 978-0-7368-6414-5.

- Tran, Nhung Tuyet; ISBN 978-0-299-21773-0.

- Hoàng, Anh Tuấn (2007). Silk for Silver: Dutch-Vietnamese Relations, 1637–1700. ISBN 978-90-04-15601-2.

- Jeffries, Ian (2007). Vietnam: A Guide to Economic and Political Developments. ISBN 978-1-134-16454-7.

- Olsen, Mari (2007). Soviet-Vietnam Relations and the Role of China 1949–64: Changing Alliances. ISBN 978-1-134-17413-3.

- Neville, Peter (2007). Britain in Vietnam: Prelude to Disaster, 1945–46. ISBN 978-1-134-24476-8.

- Smith, T. (2007). Britain and the Origins of the Vietnam War: UK Policy in Indo-China, 1943–50. ISBN 978-0-230-59166-0.

- Koskoff, Ellen (2008). The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: The Middle East, South Asia, East Asia, Southeast Asia. ISBN 978-0-415-99404-0.

- Ramsay, Jacob (2008). Mandarins and Martyrs: The Church and the Nguyen Dynasty in Early Nineteenth-century Vietnam. ISBN 978-0-8047-7954-8.

- Calò, Ambra (2009). Trails of Bronze Drums Across Early Southeast Asia: Exchange Routes and Connected Cultural Spheres. ISBN 978-1-4073-0396-3.

- Sharma, Gitesh (2009). Traces of Indian Culture in Vietnam. ISBN 978-81-905401-4-8.

- Isserman, Maurice; Bowman, John Stewart (2009). Vietnam War. ISBN 978-1-4381-0015-9.

- Koblitz, Neal (2009). Random Curves: Journeys of a Mathematician. ISBN 978-3-540-74078-0.

- Cottrell, Robert C. (2009). Vietnam. ISBN 978-1-4381-2147-5.

- Asian Development Bank (2010). Asian Development Outlook 2010 Update. ISBN 978-92-9092-181-3.

- Lockard, Craig A. (2010). Societies, Networks, and Transitions, Volume 2: Since 1450. ISBN 978-1-4390-8536-3.

- Elliott, Mai (2010). RAND in Southeast Asia: A History of the Vietnam War Era. ISBN 978-0-8330-4915-5.

- Gustafsson, Mai Lan (2010). War and Shadows: The Haunting of Vietnam. ISBN 978-0-8014-5745-6.

- Jones, Daniel (2011). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary. ISBN 978-0-521-76575-6.

- Lewandowski, Elizabeth J. (2011). The Complete Costume Dictionary. ISBN 978-0-8108-4004-1.

- Pike, Francis (2011). Empires at War: A Short History of Modern Asia Since World War II. ISBN 978-0-85773-029-9.

- Vierra, Kimberly; Vierra, Brian (2011). Vietnam Business Guide: Getting Started in Tomorrow's Market Today. ISBN 978-1-118-17881-2.

- Vo, Nghia M. (2011). Saigon: A History. ISBN 978-0-7864-8634-2.

- Khoo, Nicholas (2011). Collateral Damage: Sino-Soviet Rivalry and the Termination of the Sino-Vietnamese Alliance. ISBN 978-0-231-15078-1.

- Cooke, Nola; Li, Tana; Anderson, James (2011). The Tongking Gulf Through History. ISBN 978-0-8122-4336-9.

- Zwartjes, Otto (2011). Portuguese Missionary Grammars in Asia, Africa and Brazil, 1550–1800. ISBN 978-90-272-4608-0.

- Frankum, Ronald B. Jr. (2011). Historical Dictionary of the War in Vietnam. ISBN 978-0-8108-7956-0.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2011). The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History, 2nd Edition [4 volumes]: A Political, Social, and Military History. ISBN 978-1-85109-961-0.

- Tonnesson, Stein (2011). Vietnam 1946: How the War Began. ISBN 978-0-520-26993-4.

- Kỳ Phương, Trần; Lockhart, Bruce M. (2011). The Cham of Vietnam: History, Society and Art. ISBN 978-9971-69-459-3.

- Thaker, Aruna; Barton, Arlene (2012). Multicultural Handbook of Food, Nutrition and Dietetics. ISBN 978-1-118-35046-1.

- Keith, Charles (2012). Catholic Vietnam: A Church from Empire to Nation. ISBN 978-0-520-95382-6.

- Olson, Gregory A. (2012). Mansfield and Vietnam: A Study in Rhetorical Adaptation. ISBN 978-0-87013-941-3.

- Waite, James (2012). The End of the First Indochina War: A Global History. ISBN 978-1-136-27334-6.

- Vo, Nghia M. (2012). Legends of Vietnam: An Analysis and Retelling of 88 Tales. ISBN 978-0-7864-9060-8.

- Muehlenbeck, Philip Emil; Muehlenbeck, Philip (2012). Religion and the Cold War: A Global Perspective. ISBN 978-0-8265-1852-1.

- Rabett, Ryan J. (2012). Human Adaptation in the Asian Palaeolithic: Hominin Dispersal and Behaviour During the Late Quaternary. ISBN 978-1-107-01829-7.

- Li, Xiaobing (2012). China at War: An Encyclopedia. ISBN 978-1-59884-415-3.

- Gilbert, Adrian (2013). Encyclopedia of Warfare: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day. ISBN 978-1-135-95697-4.

- Chico, Beverly (2013). Hats and Headwear around the World: A Cultural Encyclopedia: A Cultural Encyclopedia. ISBN 978-1-61069-063-8.

- Boobbyer, Claire; Spooner, Andrew (2013). Vietnam, Cambodia & Laos Footprint Handbook. ISBN 978-1-907263-64-4.

- Fröhlich, Holger L.; Schreinemachers, Pepijn; Stahr, Karl; Clemens, Gerhard (2013). Sustainable Land Use and Rural Development in Southeast Asia: Innovations and Policies for Mountainous Areas. ISBN 978-3-642-33377-4.

- Willbanks, James H. (2013). Vietnam War Almanac: An In-Depth Guide to the Most Controversial Conflict in American History. ISBN 978-1-62636-528-5.

- Choy, Lee Khoon (2013). Golden Dragon And Purple Phoenix: The Chinese And Their Multi-ethnic Descendants In Southeast Asia. ISBN 978-981-4518-49-9.

- van Dijk, Ruud; Gray, William Glenn; Savranskaya, Svetlana; Suri, Jeremi; et al. (2013). Encyclopedia of the Cold War. ISBN 978-1-135-92311-2.

- Cosslett, Tuyet L.; Cosslett, Patrick D. (2013). Water Resources and Food Security in the Vietnam Mekong Delta. ISBN 978-3-319-02198-0.

- Lim, David (2014). Economic Growth and Employment in Vietnam. ISBN 978-1-317-81859-5.

- Gunn, Geoffrey C. (2014). Rice Wars in Colonial Vietnam: The Great Famine and the Viet Minh Road to Power. ISBN 978-1-4422-2303-5.

- Anderson, James A.; Whitmore, John K. (2014). China's Encounters on the South and Southwest: Reforging the Fiery Frontier Over Two Millennia. ISBN 978-90-04-28248-3.

- de Mora, Javier Calvo; Wood, Keith (2014). Practical Knowledge in Teacher Education: Approaches to teacher internship programmes. ISBN 978-1-317-80333-1.

- Eggleston, Michael A. (2014). Exiting Vietnam: The Era of Vietnamization and American Withdrawal Revealed in First-Person Accounts. ISBN 978-0-7864-7772-2.

- Dennell, Robin; Porr, Martin (2014). Southern Asia, Australia, and the Search for Human Origins. ISBN 978-1-107-72913-1.

- Hong Lien, Vu; Sharrock, Peter (2014). Descending Dragon, Rising Tiger: A History of Vietnam. ISBN 978-1-78023-388-8.

- Gibbons, William Conrad (2014). The U.S. Government and the Vietnam War: Executive and Legislative Roles and Relationships, Part III: 1965–1966. ISBN 978-1-4008-6153-8.

- Ooi, Keat Gin; Anh Tuan, Hoang (2015). Early Modern Southeast Asia, 1350–1800. ISBN 978-1-317-55919-1.

- Oxenham, Marc; Buckley, Hallie (2015). The Routledge Handbook of Bioarchaeology in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. ISBN 978-1-317-53401-3.

- Duy Hinh, Nguyen; Dinh Tho, Tran (2015). The South Vietnamese Society. Normanby Press. ISBN 978-1-78625-513-6.

- Yao, Alice (2016). The Ancient Highlands of Southwest China: From the Bronze Age to the Han Empire. ISBN 978-0-19-936734-4.

- Howe, Brendan M. (2016). Post-Conflict Development in East Asia. ISBN 978-1-317-07740-4.

- Thanh Hai, Do (2016). Vietnam and the South China Sea: Politics, Security and Legality. ISBN 978-1-317-39820-2.

- Phuong Linh, Huynh Thi (2016). State-Society Interaction in Vietnam. ISBN 978-3-643-90719-6.

- Ozolinš, Janis Talivaldis (2016). Religion and Culture in Dialogue: East and West Perspectives. ISBN 978-3-319-25724-2.

- Howard, Michael C. (2016). Textiles and Clothing of Việt Nam: A History. ISBN 978-1-4766-2440-2.

- Kiernan, Ben (2017). Việt Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present. ISBN 978-0-19-516076-5.

- DK (2017). The Vietnam War: The Definitive Illustrated History. ISBN 978-0-241-30868-4.

- Travel, DK (2017). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide Vietnam and Angkor Wat. ISBN 978-0-241-30136-4.

- Moïse, Edwin E. (2017). Land Reform in China and North Vietnam: Consolidating the Revolution at the Village Level. ISBN 978-0-8078-7445-5.

- Hinchey, Jane (2017). Vietnam: Discover the Country, Culture and People. Redback Publishing. ISBN 978-1-925630-02-2.

- Kort, Michael (2017). The Vietnam War Re-Examined. ISBN 978-1-107-04640-5.

- Trieu Dan, Nguyen (2017). A Vietnamese Family Chronicle: Twelve Generations on the Banks of the Hat River. ISBN 978-0-7864-8779-0.

- Tran, Tri C.; Le, Tram (2017). Vietnamese Stories for Language Learners: Traditional Folktales in Vietnamese and English Text (MP3 Downloadable Audio Included). ISBN 978-1-4629-1956-7.

- Tran, Anh Q. (2017). Gods, Heroes, and Ancestors: An Interreligious Encounter in Eighteenth-Century Vietnam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-067760-2.

- Cosslett, Tuyet L.; Cosslett, Patrick D. (2017). Sustainable Development of Rice and Water Resources in Mainland Southeast Asia and Mekong River Basin. ISBN 978-981-10-5613-0.

- Zhu, Ying; Ren, Shuang; Collins, Ngan; Warner, Malcolm (2017). Business Leaders and Leadership in Asia. ISBN 978-1-317-56749-3.

- Dohrenwend, Bruce P.; Turse, Nick; ISBN 978-0-19-090444-9.

- Lamport, Mark A. (2018). Encyclopedia of Christianity in the Global South. ISBN 978-1-4422-7157-9.

- Dinh Tham, Nguyen (2018). Studies on Vietnamese Language and Literature: A Preliminary Bibliography. ISBN 978-1-5017-1882-3.

- Dayley, Robert (2018). Southeast Asia in the New International Era. ISBN 978-0-429-97424-3.

- Chen, Steven (2018). The Design Imperative: The Art and Science of Design Management. ISBN 978-3-319-78568-4.

- Wilcox, Wynn, ed. (2010). Vietnam and the West: New Approaches. Ithaca, NY: ISBN 978-0-87727-782-8.

Legislation and government source

- "Chapter Five: Fundamental Rights and Duties of the Citizen". Constitution of Vietnam. 1992. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018 – via Ministry of Justice (Vietnam).

- "Annexe au procès-verbal de la séance du 1er octobre 1997". French Senate (in French). 1997.

- "Penal Code (No. 15/1999/QH10)". Ministry of Justice. Vietnam. 1999. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013.

- "Law on Publication (No. 30/2004/QH11)". Ministry of Justice. Vietnam. 2004. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011.

- "Ordinance of Beliefs and Religion [No. 21]". Ministry of Justice. Vietnam. 2004. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018.

- "Report on International Religious Freedom: Vietnam". US Department of State. 2019.

- "International Religious Freedom Report 2006". United States Department of State. 2005.

- "U.S. Humanitarian Mine Action Programs: Asia". United States Department of State. 2006.

- Trung Chien, Tran Thi (2006). "Vietnam Health Report" (PDF). Ministry of Health. Vietnam. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2018.

- Nielsen, Chantal Pohl (2007). "Vietnam's Rice Policy: Recent Reforms and Future Opportunities" (PDF). Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. Vietnam. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2018.

- "Vietnamese general company of rubber-prospect of being a foremost Vietnamese agriculture group". AgroViet Newsletter. 2007. Archived from the original on 21 February 2008.

- "Vietnam Foreign Policy". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Vietnam. 2007. Archived from the original on 18 January 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- "MEDIA RELEASE: The 2009 Population and Housing Census". General Statistics Office of Vietnam. 2009. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010.

- Mạnh Cường, Nguyễn; Ngọc Lin, Nguyễn (2010). "Giới thiệu Quốc hoa của một số nước và việc lựa chọn Quốc hoa của Việt Nam" [Introducing the national flower of some countries and the selection of national flower of Vietnam]. National Archives of Vietnam (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 12 April 2019.

- "Transport, Postal Services and Telecommunications". General Statistics Office of Vietnam. 2010. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018.

- Fong-Sam, Yolanda (2010). "The Mineral Industry of Vietnam" (PDF). 2010 Minerals Yearbook. United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2013.

- Taylor, Claire; Rutherford, Tom (2011). "Military Balance in Southeast Asia [Research Paper 11/79]" (PDF). House of Commons Library.

- "Monthly statistical information – Social and economic situation, 8 months of 2011 [Traffic accidents]". General Statistics Office of Vietnam. 2011. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018.

- Green, Michael (2012). "Foreign policy and diplomatic representation". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- "Bộ Luật Lao Động (No. 10/2012/QH13)". Ministry of Justice (in Vietnamese). Vietnam. 2012. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018.

- "Key ingredients: Vietnamese". Special Broadcasting Service. Australia. 2013. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018.

- "Vietnam [The Full Picture of Vietnam]" (PDF). Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration. Canada. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2018.

- "General Information about Countries and Regions [List of countries which maintains diplomatic relations with the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (as April 2010)]". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Vietnam. 2013. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- "Nha Trang city: Vietnamese cultural cuisine festival 2014 opens". Vietnam Culture Information Network. 2014. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- "Conquering the Fansipan". Vietnam National Administration of Tourism. 2014. Archived from the originalon 2 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- "Continue moving forward with intensive international integration". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Vietnam. 2014.

- "Số liệu thống kê – Danh sách". General Statistics Office of Vietnam (in Vietnamese). 2015.

- "Minister Schultz signs agreement on water treatment project in Vietnam". Government of the Netherlands. 2016.

- Garamone, Jim (2016). "Lifting Embargo Allows Closer U.S., Vietnam Cooperation, Obama, Carter Say". United States Department of Defense.

- "UK aid helps clear lethal landmines in war-torn countries following generosity of British public". Government of the United Kingdom. 2017.

- "Speech by Cora van Nieuwenhuizen, Minister of Infrastructure and Water Management, at the celebration of 45 years of bilateral relations with Vietnam, Hilton Hotel The Hague, 26 March 2018". Government of the Netherlands. 2018.

- "Russia and Vietnam draft International Military Activity Plan 2020". Ministry of Defence. Russia. 2018.

- "UK trade with Vietnam – looking to the next 45 years". Government of the United Kingdom. 2018.

- Anh, Van (2018). "Vietnam and Netherlands reaffirm economic relations". Vietnam Investment Review. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019.

- "Contract signed for feasibility study for Long Thanh airport". Vietnam Investment Review. 2018. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018.

- "Vietnam and International Organizations". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Vietnam. 2018.

- "International visitors to Viet Nam in December and 12 months of 2017". Vietnam National Administration of Tourism. 2018. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019.

- "Overview on Vietnam geography". Government of Vietnam. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- "About Vietnam (Political System)". Government of Vietnam. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- "An Overview of Spatial Policy in Asian and European Countries". Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. Japan.

- "Environmental Remediation [Agent Orange]". United States Agency for International Development. 3 December 2018.

- "Tài Liệu Cơ Bản Nước Cộng Hoà Hồi Giáo Pa-kít-xtan". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (in Vietnamese). Vietnam.

- "Báo cáo Hiện trạng môi trường quốc gia 2005 Chuyên đề Đa dạng sinh học". Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (in Vietnamese). Vietnam. Archived from the original on 23 February 2009.

- ISBN 978-604-75-1532-5.

Academic publications

- Crozier, Brian (1955). "The Diem Regime in Southern Vietnam". Far Eastern Survey. 24 (4): 49–56. JSTOR 3023970.

- Gittinger, J. Price (1959). "Communist Land Policy in North Viet Nam". Far Eastern Survey. 28 (8): 113–126. JSTOR 3024603.

- JSTOR 834104.

- Riehl, Herbert; Augstein, Ernst (1973). "Surface interaction calculations over the Gulf of Tonkin". Tellus. 25 (5): 424–434. .

- .

- Fraser, SE (1980). "Vietnam's first census". POPLINE. 8 (8). Intercom: 326–331. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Higham, C.F.W. (1984). "Prehistoric Rice Cultivation in Southeast Asia". Scientific American. 250 (4): 138–149. JSTOR 24969352.

- Nguyen, Lan Cuong (1985). "Two early Hoabinhian crania from Thanh Hoa Province, Vietnam". Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie. 77 (1): 11–17. PMID 3564631.

- JSTOR 43562680.

- Gough, Kathleen (1986). "The Hoa in Vietnam". Contemporary Marxism, Social Justice/Global Options (12/13): 81–91. JSTOR 29765847.

- Kimura, Tetsusaburo (1986). "Vietnam—Ten Years of Economic Struggle". Asian Survey. 26 (10): 1039–1055. JSTOR 2644255.

- Quach Langlet, Tâm (1991). "Charles Fourniau: Annam-Tonkin 1885–1896. Lettrés et paysans vietnamiens face à la conquête coloniale. Travaux du Centre d'Histoire et Civilisations de la péninsule Indochinoise". Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient (in French). 78 – via Persée.

- Huu Chiem, Nguyen (1993). "Geo-Pedological Study of the Mekong Delta" (PDF). Southeast Asian Studies. 31 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018 – via Kyoto University.

- Thayer, Carlyle A. (1994). "Sino-Vietnamese Relations: The Interplay of Ideology and National Interest". JSTOR 2645338.

- Greenfield, Gerard (1994). "The Development of Capitalism in Vietnam". Socialist Register. Archived from the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- Hirschman, Charles; Preston, Samuel; Manh Loi, Vu (1995). "Vietnamese Casualties During the American War: A New Estimate". Population and Development Review. 21 (4): 783–812. JSTOR 2137774.

- Goodkind, Daniel (1995). "Rising Gender Inequality in Vietnam Since Reunification". Pacific Affairs. 68 (3): 342–359. JSTOR 2761129.

- Amer, Ramses (1996). "Vietnam's Policies and the Ethnic Chinese since 1975". Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia. 11 (1): 76–104. JSTOR 41056928.

- Momoki, Shiro (1996). "A Short Introduction to Champa Studies" (PDF). Kyoto University Research Information Repository. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2018 – via CORE.

- Meacham, William (1996). "Defining the Hundred Yue". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 15: 93–100. doi:10.7152/bippa.v15i0.11537 (inactive 31 March 2024).)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of March 2024 (link - Jacques, Roland (1998). "Le Portugal et la romanisation de la langue vietnamienne. Faut- il réécrire l'histoire ?". Outre-Mers. Revue d'Histoire (in French). 318 – via Persée.

- Zinoman, Peter (2000). "Colonial Prisons and Anti-Colonial Resistance in French Indochina: The Thai Nguyen Rebellion, 1917". S2CID 145191678.

- Xuan Dinh, Quan (2000). "The Political Economy of Vietnam's Transformation Process". Contemporary Southeast Asia. 22 (2): 360–388. JSTOR 25798497.

- Moise, Edwin E. (1988). "Nationalism and Communism in Vietnam". Journal of Third World Studies. 5 (2). University Press of Florida: 6–22. JSTOR 45193059.

- Matsumura, Hirofumi; Lan Cuong, Nguyen; Kim Thuy, Nguyen; Anezaki, Tomoko (2001). "Dental Morphology of the Early Hoabinian, the Neolithic Da But and the Metal Age Dong Son Civilized Peoples in Vietnam". Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie. 83 (1): 59–73. PMID 11372468.

- Emmers, Ralf (2005). "Regional Hegemonies and the Exercise of Power in Southeast Asia: A Study of Indonesia and Vietnam". JSTOR 10.1525/as.2005.45.4.645.

- Endres, Kirsten W. (2001). "Local Dynamics of Renegotiating Ritual Space in Northern Vietnam: The Case of the "Dinh"". Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia. 16 (1): 70–101. PMID 19195125.

- McLeod, Mark W.; Thi Dieu, Nguyen (2001). Culture and Customs of Vietnam. Culture and Customs of Asia. ISSN 1097-0738.