Meiji Restoration

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

| Part of the end of the Edo period | |

Emperor Meiji in 1873 | |

| Native name | 明治維新 (Meiji Ishin) |

|---|---|

| Date | 3 January 1868 |

| Location | Japan |

| Outcome |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Japan |

|---|

|

The Meiji Restoration (

The origins of the Restoration lay in economic and political difficulties faced by the

On 3 January 1868, Emperor Meiji declared political power to be restored to the Imperial House. The goals of the restored government were expressed by the new emperor in the

Background

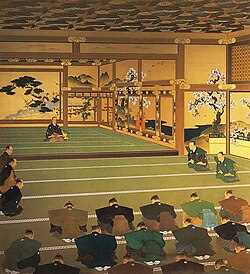

Political and social structure

Japan in the Edo period was governed by a strict and rigid social order with inherited position. This hierarchy in descending order had the Emperor and their Court at the top. The shōgun, with the rōjū and daimyō below him inhabited the upper strata of society. Below them were various subdivisions of samurai, farmers, artisans, and merchants.[2] Historian Marius B. Jansen refers to the political organisation of the system as being one of "feudal autonomy".[3] This was a structure of government where the shōgun, the principal organiser of the military dictatorship, granted extensive control to the various daimyō over their own domains to control their own jurisdiction while paying homage to him through irregular taxation, the seeking of permission for marriage and movement,[4] and systems such as that of alternate attendance.[5] The total population of samurai families in the 19th century numbered around 5-6% of 30 million people (1,500,000-1,800,000), among these families, roughly 1 in 50 was an "upper samurai" while the rest were divided mostly evenly between "middle" and "lower" samurai, with each division containing more subdivisions.[6]

The influence exerted by the Tokugawa shogunate (bakufu) in contemporary Japan was built on the distribution and management of land. Split into domains, each domain was measured by koku, or the amount of rice a given area of land could produce per annum. By 1650, the shōgun directly controlled land producing roughly 4.2 million koku of rice, with his direct retainers, other members of the Tokugawa family (shinpan daimyō), and his vassals (fudai daimyō) controlling a combined total of land producing 12.9 million koku out of a national 26 million koku. The remaining 9.8 million koku (just under 38%) was parceled out between about 100 rival tozama daimyō, the descendants of those who had fought against the Tokugawa at the Battle of Sekigahara. Many of the strongest tozama domains were located in western Japan away from centres of power, with the fudai often controlling government offices, but with smaller provinces to incentivize them to preserve the system.[7]

According to the

Ideological currents

Beginning especially in the last quarter of the 18th century, a kind of

Sakuma Shōzan was a midranking samurai under the daimyō Sanada Yukinori of Matsushiro Domain, he held a conservative attitude to the social development of Japanese society, but was practical in his approach to the adoption of Western technology. He supplemented his view of Neo-Confucian ethics with that of the adoption of foreign scientific methods,[17] coining the phrase "Eastern ethics, Western science".[b][18] In addition to writing about the need for coastal defense, he took charge over cannon founding, built his own camera, and wrote a Japanese-English dictionary designed to contribute to the defense of Japan.[17] He opened a school in Edo, teaching over 5,000 students from all over the country.[19] His efforts to promote men of talent (who would be drawn exclusively from the samurai class), and reorganise the Japanese military were incredibly influential among his disciples, not least Katsu Kaishū and Yoshida Shōin. However, they would serve as the foundation for proposals that would change the social order he was attempting to preserve.[17]

Economic development

The

Fixed rice

The changing economic history of the Edo period drastically altered the traditionally rigid social hierarchy of Tokugawa Japan, with new land becoming available for cultivation and new outlets for commercial trade and manufacturing. Beyond changing the nature of value in local economies, these changes brought with them an erosion of the official class system, with some domains offering the sale of samurai status, and many rich commoners educating their children and bribing their way into adoption by poor samurai families.

Foreign influence, 1633-1854

Since 1633 a system of national isolation known as sakoku had been imposed by the Tokugawa shogunate wherein no person was allowed to enter or leave the country without permission from the shōgun. The resultant isolationism fuelled systemic diversification of the domestic economy to fulfil local needs. This socio-cultural development combined with strict regulation and censorship on the topic of politics created a "seldom penetrated" lack of international consciousness.[30] Following the Shimabara Rebellion, the non-Catholic Dutch had been permitted to maintain a monopoly through their factory on Dejima, just off the coast of Nagasaki in Saga domain.[31] This trade, although limited in scope, had led to a growing understanding of the West by Tokugawa intellectuals.[30]

Russian Empire

Over the course of the Edo period, a number of incidents had occurred where Russians had come into contact with Japanese people due to exploration east by the former and north by the latter. In 1804

Western Europe

During the Napoleonic Wars,

The threat of the Western powers became far more pronounced when news of Britain's success in the

United States of America

Appointed to command the American expedition in 1852,

Less than a year later Perry returned in threatening

End of the Tokugawa shogunate

Reactions to the Unequal Treaties, 1854-1858

The anti-treaty faction was horrified at the extent of the concessions made by Abe Masahiro to Perry in the Convention of Kanagawa. Even reformers who had advocated for compromise were upset at the magnitude of concessions made.[50] From the Mito School, Fujita Yūkoku's disciple Aizawa Seishisai extended his teacher's ideas, writing the Shinron ("New Theses") in 1825.[d] Advocating a will to resist, Aizawa believed a policy of sonnō jōi ("revere the Emperor, expel the barbarian") would create a unity and resolution among the people. The shōgun would be responsible for subordinating the interests of the Tokugawa family to those of the Japanese people, by revering the Emperor as a symbol of the kokutai or national polity.[52] The positions of opening the country and taking up arms against foreign powers were not mutually exclusive, and believers both in jōi and kaikoku realised the advantages of Western technology for the purpose of repelling the foreigners.[53] Abe resigned as senior rōju and was replaced by Hotta Masayoshi beginning in 1855.[54][55] An outcome of this decision was the estrangement of Tokugawa Nariaki from the senior council as Hotta continued to drive in a reformist direction.[56][57]

The

With the provisions of

Political violence, 1858-1864

Aware of how unpopular the treaty was, Ii Naosuke took his prerogative to be the restoration of strong, centralised bakufu governance. In pursuit of this aim, he enacted the

As Ii continued to centralise power around the shogunate, one of the people caught in his purges was the samurai intellectual Yoshida Shōin. A pupil of Sakuma Shōzan, Yoshida was what came to be known as a shishi, a "man of spirit".[72] The shishi were low and middle-ranking samurai who were filled with reverence for the Imperial Court at Kyōto in which lay the essential quality of national purity.[73] This was an ideological fusion based on Mito School kokugaku studies of Neo-Confucian principles of loyalty and the Shintō revival of the early 19th century, with shishi believing loyalty to the Emperor to be of the utmost importance.[74] They saw the bakufu as becoming increasingly self-interested, with the daimyō unwilling to intervene in mediating open disagreement between the Imperial Court and the bakufu over the issue of the foreign threat. The crisis of 1858 had changed Yoshida's perspective, where before he had been open to conciliation between the Court and bakufu, he now believed the shishi should take direct action in response to the actions of the bakufu and daimyō. Yoshida's increasingly extreme teachings lost him the support of influential samurai, as well as his own pupils (including Kido Takayoshi and Takasugi Shinsaku).[75] He was executed in 1859 for planning the assassination of Manabe Akikatsu.[76]

The culmination of unrest among lower-samurai in response to the heavy-handed exercise of authority by the bakufu occurred when Ii was assassinated in 1860. This action engendered a new violent consciousness centred on the principle of sonnō jōi. Later that same year, Tokugawa Nariaki died while still under confinement.[77] Jansen writes that, in the aftermath of the killing, many lower and middle-ranking samurai began to see a means to effect "changes to their personal and collective position".[78] In Satsuma Domain, a loyalist group under Ōkubo Toshimichi moved towards conciliation with the domain officials, concerning themselves with persuading the daimyō to break with the bakufu cause; Saigō Takamori would join this group upon return from his exile in 1862.[79] In Tosa Domain, Takechi Hanpeita met with Kido Takayoshi and Kusaka Genzui who shared their martyred teacher's philosophy. Formalising his leadership over a group of local shishi in October 1861, the loyalist party (among whom was counted Sakamoto Ryōma, although he left in 1862[80]) did not view their loyalty to the Emperor as contradictory to their traditional feudal loyalties.[81]

The shishi loyalists achieved some success in national politics, successfully renegotiating the conditions of kōbu gattai to favour the Imperial Court through their co-operation with the Chōshū government.[82] Shishi were promoted in these regions (Ōkubo in Satsuma Domain, and Kido in Chōshū—both of whom were seen to be a moderating force against extremists), but they did not represent a majority view of domain officials.[83] Despite the politics of Chōshū Domain being decidedly more moderate than the advice of the Chōshū loyalists in Kyōto,[83] the regent of Satsuma Domain, Shimazu Hisamitsu was angry at the amount of influence Chōshū Domain shishi were having on Court politics.[84]

Foreign intervention

During a mission to Kyōto regarding the position of the Imperial Court in the political authority of the bakufu to order the expulsion of the foreigners, the retainers of Shimazu Hisamitsu's procession

The Shimonoseki agreement to end the foreign attacks signed by the bakufu in October 1864 signalled a shift in policy that prioritised dealing with the foreign powers in a nonantagonistic manner. The bakufu would marshal its influence against the Imperial Court whenever they agitated for a policy of jōi. Similarly, the burgeoning anti-Tokugawa movement was shifting ideological emphasis away from direct expulsion towards fukoku kyōhei (rich nation, strong army) as a way to deal with the threat posed by the foreign powers.[91] Indicative of this is that, just prior to this time, Sakamoto Ryōma met Katsu Kaishū intending to assassinate him for his perceived pro-foreign beliefs, what occurred instead was a conversation wherein Ryōma became convinced by Kaishū's plan for rearmament, following Kaishū when he later established the Kobe Naval Training Centre in 1863.[92][93] As bakufu power began to be challenged, a split emerged between the foreign powers; France, represented by Léon Roches favoured bolstering the Tokugawa to deal with internal strife, whereas Britain's minister Harry Parkes increasingly began to favour dealing with the southwest domains of Satsuma and Chōshū.[94]

The anti-Tokugawa alliance and domain rebellion, 1864-1867

A period of conservative reaction against the shishi followed the military failures of 1863 and 1864.[95] It was during this period of backlash against the sonnō jōi ideology of the loyalists that Takechi Hanpeita was arrested and compelled to commit seppuku by the daimyō of Tosa Domain Yamauchi Yōdō.[96] Following the death of Tokugawa Nariaki in 1860, Mito Domain had been dominated by upper-ranking conservative samurai who favoured conciliation with the Tokugawa bakufu, but a power struggle developed from the belief that the bakufu's pro-foreign tendencies were threatening the Imperial Court's expulsion edict. With news of uprisings in Yamato and Tajima, in May 1864 pro-sonnō jōi loyalists declared the Mito Rebellion in defiance of the bakufu.[97]

Beasley identifies two principle lessons from the military defeat of the Mito Rebellion, the requirement of one of the great domains to support the movement and the division within the social structure of Restoration politics.[98] The shishi, being predominantly lower-ranking samurai of the rural elite, were abandoned by the local peasantry (poorer farmers either abandoned or joined the bakufu forces in attacking the loyalists). Similarly, the tepid support for (in the case of Mito) or the criticism of (in Yamato and Tajima) the revolts of the lower-ranking samurai by the more moderate middle-ranking samurai, shifted the emphasis towards "a political method more in conformity with the needs of feudal society."[99] By the spring of 1864, Satsuma Domain policy had shifted to moderation, seeking the removal of shishi influence from the Court and its domain government, as part of this policy they worked with the bakufu to violently suppress the shishi in Kyōto. As a result, Chōshū became the last refuge for sonnō jōi loyalists. A power struggle over the domain's politics soon followed, as did a contest between bakufu and domain political power.[100]

In Chōshū, the remnant shishi organised themselves into militias (e.g. the

Despite the rōju advocating for the execution of Chōshū's daimyō Mōri Takachika,[104] the result of the settlement was relatively generous to Chōshū, due in part to the intervention of Katsu Kaishū and Saigō.[105] As such, when the expedition disbanded, the Chōshū militias submitted a memorandum to the domain government chastising them for aquiescing to the bakufu's demands. Then, in early 1865 Takasugi launched an attack on the domain government. The Kiheitai under Yamagata Aritomo joined the attack, and the domain government quickly ousted the conservatives who had been restored to power following the bakufu's punitive expedition.[106] The loyalists advocated for turning from a position of foreign expulsion to fukoku kyōhei, with Itō Hirobumi, Inoue Kaoru and Ōmura Masujirō joining Takasugi and Kido in seeking to open the port of Shimonoseki for trade in order to import foreign weapons.[107]

The Satsuma-Chōshū Alliance

Beasley identifies three issues in Japanese politics until this point: that of foreign policy, that of Tokugawa authority, and that of feudal discipline. In reducing the importance of jōi sentinment in Chōshū, the first issue was no longer divisive; the incorporation or destruction of shishi loyalists by the domain governments across Japan had solved many problems related to the third issue; this left the question of bakufu power at the centre of national politics.[108] Until this point, Satsuma Domain's cooperation with the bakufu in the Hamaguri Gate Rebellion and subsequent punitive expedition had been a point of tension and mistrust with Chōshū Domain.[109] However, continued bakufu designs to destroy Chōshū pushed Saigō Takamori to reject the prerogatives of the Tokugawa, he appealed to the domain regent Shimazu Hisamitsu and began buying weaponry from the British.[110] Meanwhile, Sakamoto Ryōma assisted Chōshū loyalists to bypass the bakufu's prohibition on domain weapons trade by setting up connections to British merchants via his firm in Nagasaki. From here he laid the logistical and diplomatic foundations for co-operation between the two domains.[111] On 7 March 1866, Sakamoto successfully brought together Kido Takayoshi and Saigō Takamori to formalise an alliance between Satsuma and Chōshū.[112]

Planning for the Second Chōshū expedition sought to end the possibility of domain resistance to Tokugawa authority.[113] When hostilities became inevitable by the summer of 1866, Chōshū moved quickly to repulse or forestall any bakufu operations.[114] When the bakufu sent out requests among Chōshū's neighbouring domains to assist in shogunal efforts, the domains offered noncommittal or hostile responses. Many of the daimyō were suspicious of bakufu aims and were concerned about encroaching French influence in the bakufu's capability to build a centralised state.[113] Satsuma regent Shimazu Hisamitsu expressed a widely-held belief in a memorial to the Imperial Court that accused the bakufu of seeking a draconian settlement with Chōshū that risked the safety of the country at large.[115] The simultaneous death of shōgun Tokugawa Iemochi caused the bakufu to seek a truce.[114]

The restoration movement

Shortly following the success of Chōshū against the bakufu, Court noble Iwakura Tomomi suggested the Emperor agitate openly for full imperial restoration,[f] but the Court remained cautious of overplaying their hand.[116] At the same time, the daimyō had their own designs for restructuring the system of feudal autonomy that did not fully correspond with his proposal.[117] Emperor Kōmei died in February 1867, leaving the teenager Mutsuhito to ascend to the throne as Emperor Meiji.[118] Offers for a mediated settlement were proposed by the new shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu; but when they were ignored the bakufu instituted a series of reforms to the military, administration, and finance.[119] These serious efforts at reform sparked worries among some in the anti-Tokugawa alliance, and in 1867, Saigō and Ōkubo Toshimichi both wrote to Shimazu to indicate their support for returning the country's administration to the power of the Emperor.[120]

At the urging of Saigō and Ōkubo, four daimyō (Date Munenari, Matsudaira Yoshinaga, Yamauchi, and the regent Shimazu) sent to negotiate with the shōgun over the opening the port at Kōbe and the policy towards Chōshū repudiated the compromise they made with Tokugawa Yoshinobu. In late June, they publicly disputed the shōgun's account in the Imperial Court when Tokugawa attempted to take advantage of a fractured opposition to assert the traditional authority of the shōgun.[121][122] As plans formalised among the anti-Tokugawa alliance, Sakamoto drafted an Eight Point Plan that would serve as the foundation of restoration politics.[123] It included provisions for expanding the military, reform of the law, establishing a bicameral legislature, and the return of political power to the Imperial Court.[124][125] As a representative of Tosa Domain, Sakamoto was seeking to position himself between the Satchō alliance and the bakufu and submitted his proposals to the Tosa Domain government,[126][125] which became the basis for plans submitted to the shōgun to persuade him to resign his powers.[127]

Imperial restoration

Dissolution of the shogunate, 1867

With the domains preparing to use military force to remove the bakufu government,[128] the Tosa Domain memorandum was submitted to Tokugawa Yoshinobu at a time when some of the shōgun's advisors were advocating for similar reforms.[129] Seeking to maintain his title and influence,[130][131] on 8 November 1867, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the 15th Tokugawa shōgun, decided to renounce the administrative functions of his office and returned the power to the Imperial Court.[132] The following day, the Court received the memorandum, but also sent a rescript authorising the domain governments to use military force to oust the bakufu.[g][130] Ten days later on 19 November, Tokugawa also resigned the title of shōgun. As Tokugawa remained inert in temporarily exercising his authority, the Court was divided, while the daimyō continued planning for a violent confrontation.[134] Iwakura Tomomi, Saigō Takamori, and Ōkubo Toshimichi spent the months of November and December organising a coup d'état within the divided Imperial Court, with the aim to strip the Tokugawa house of their lands held in fief. This would prevent them from dominating the future council of daimyō.[135]

The suspicion and disorder that accompanied the shōgun's resignation led to violence in Kyōto, during which Sakamoto Ryōma was assassinated.[136] Tosa Domain had sponsored the shōgun's abdication request, but Satsuma and Chōshū officials were intent on establishing their domains at the centre of a new system.[131] The requirement for Satsuma and Chōshū to demonstrate they were acting in accordance with the wishes of the Emperor led them to formulate the 3 January proclamation, making the Imperial Court's antibakufu stance official.[137] In analysing how the Tokugawa shogunate collapsed so suddenly, Jansen indicates that the division of the bakufu's network of feudal relations had its attention split between focus on the Imperial Court and individual preoccupation with domain affairs. The office of shōgun suffered an erosion of authority as domain bureaucrats began exercising their power over policy to promote their leadership over other domains'; this evolved into a programme realised by individual personalities and military force.[138]

January Proclamation, 1868

In the early hours of 3 January 1868, domain troops seized control of the Imperial Palace from the bakufu while Iwakura simultaneously received official approval from the Emperor for these actions.

The Emperor of Japan announces to the sovereigns of all foreign countries and to their subjects that permission has been granted to the

Mutsuhito, January 3, 1868[142]

Despite the new government being in a state of precarity, public placards and

The Boshin War, 1868-1869

Recognising that the Court had made a mistake in allowing Tokugawa autonomy, Ōkubo contacted Iwakura and the Satchō military officers to take action before Tokugawa could re-establish his influence among the daimyō. On the 27 January, the Battle of Toba–Fushimi took place, in which Chōshū and Satsuma's forces defeated the Tokugawa's army.[148] Seeking to avoid a full civil war, Tokugawa retreated to Edo by sea and refused to counter-attack.[149] An Imperial decree on 31 January blamed the Tokugawa for starting hostilities and Ōsaka Castle surrendered three days later. The army moved to take Edo during late February,[150] then on 1 March, Prince Arisugawa was made supreme commander of the Imperial forces during the campaign.[151]

The Court, seeking improved relations with the foreigners, issued orders that brought their military conduct in alignment with international standards, and on 23 March the Dutch minister Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek and the French minister Léon Roches became the first European envoys to receive a personal audience with Meiji.[152] Seeking a negotiated settlement, Tokugawa wrote to Saigō Takamori and elevated Katsu Kaishū to a position with the authority to represent the Tokugawa house. In April, Katsu and Saigō met to discuss the conditions that would be faced by Tokugawa. Both sides agreed to Tokugawa surrendering himself, his castle, and military force.[150] Iwakura took this agreement and stipulated that Tokugawa Yoshinobu resign as head of the family and surrender all but 700,000 koku of his lands, a deal that Tokugawa accepted on 3 May.[153]

Some Emperor loyalists were unsatisfied with what they considered to be lenient conditions, meanwhile, troops of the

In 1869, the daimyō of the

Imperial reform

Emperor Meiji announced in his 1868 Charter Oath that "Knowledge shall be sought all over the world, and thereby the foundations of imperial rule shall be strengthened."[156]

All Tokugawa lands were seized and placed under "imperial control", thus placing them under the prerogative of the new Meiji government. With Fuhanken sanchisei, the areas were split into three types: urban prefectures (府, fu), rural prefectures (県, ken) and the already existing domains. In 1868, the koban was discontinued as a form of currency.

Under the leadership of

The Meiji oligarchy that formed the government under the rule of the Emperor first introduced measures to consolidate their power against the remnants of the Edo period government, the shogunate, daimyōs, and the samurai class.[157]

Throughout Japan at the time, the samurai numbered 1.9 million. For comparison, this was more than 10 times the size of the French privileged class before the 1789 French Revolution. Moreover, the samurai in Japan were not merely the lords, but also their higher retainers—people who actually worked. With each samurai being paid fixed stipends, their upkeep presented a tremendous financial burden, which may have prompted the oligarchs to action.

Whatever their true intentions, the oligarchs embarked on another slow and deliberate process to abolish the samurai class. First, in 1873, it was announced that the samurai stipends were to be taxed on a rolling basis. Later, in 1874, the samurai were given the option to convert their stipends into government bonds. Finally, in 1876, this commutation was made compulsory.[citation needed]

To reform the military, the government instituted nationwide conscription in 1873, mandating that every male would serve for four years in the armed forces upon turning 21 years old, followed by three more years in the reserves. One of the primary differences between the samurai and peasant classes was the

This led to a series of riots from disgruntled samurai. One of the major riots was the one led by Saigō Takamori, the Satsuma Rebellion, which eventually turned into a civil war. This rebellion was, however, put down swiftly by the newly formed Imperial Japanese Army, trained in Western tactics and weapons, even though the core of the new army was the Tokyo police force, which was largely composed of former samurai. This sent a strong message to the dissenting samurai that their time was indeed over. There were fewer subsequent samurai uprisings and the distinction became all but a name as the samurai joined the new society. The ideal of samurai military spirit lived on in romanticised form and was often used as propaganda during the early 20th-century wars of the Empire of Japan.[158]

However, it is equally true that the majority of samurai were content despite having their status abolished. Many found employment in the government bureaucracy, which resembled an elite class in its own right. The samurai, being better educated than most of the population, became teachers, gun makers, government officials, and/or military officers. While the formal title of samurai was abolished, the elitist spirit that characterised the samurai class lived on.[citation needed]

The oligarchs also embarked on a series of

The military of Japan, strengthened by nationwide conscription and emboldened by military success in both the First Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War, began to view themselves as a growing world power.

Aftermath

Centralization

Besides drastic changes to the social structure of Japan, in an attempt to create a strong centralized state defining its national identity, the government established a dominant national dialect, called "standard language" (標準語,

The Meiji Restoration, and the resultant modernization of Japan, also influenced Japanese self-identity with respect to its Asian neighbors, as Japan became the first Asian state to modernize based on the Western model, replacing the traditional Confucian hierarchical order that had persisted previously under a dominant China with one based on modernity.[160] Adopting enlightenment ideals of popular education, the Japanese government established a national system of public schools.[161] These free schools taught students reading, writing, and mathematics. Students also attended courses in "moral training" which reinforced their duty to the Emperor and to the Japanese state. By the end of the Meiji period, attendance in public schools was widespread, increasing the availability of skilled workers and contributing to the industrial growth of Japan.

The opening up of Japan not only consisted of the ports being opened for trade, but also began the process of merging members of the different societies together. Examples of this include western teachers and advisors immigrating to Japan and also Japanese nationals moving to western countries for education purposes. All these things in turn played a part in expanding the people of Japan's knowledge on western customs, technology and institutions. Many people believed it was essential for Japan to acquire western "spirit" in order to become a great nation with strong trade routes and military strength.[citation needed]

Industrial growth

The Meiji Restoration accelerated the

There were a few factories set up using imported technologies in the 1860s, principally by Westerners in the international settlements of Yokohama and Kobe, and some local lords, but these had relatively small impacts. It was only in the 1870s that imported technologies began to play a significant role, and only in the 1880s did they produce more than a small output volume.[162] In Meiji Japan, raw silk was the most important export commodity, and raw silks exports experienced enormous growth during this period, overtaking China. Revenue from silk exports funded the Japanese purchase of industrial equipment and raw materials. Although the highest quality silk remained produced in China, and Japan's adoption of modern machines in the silk industry was slow, Japan was able to capture the global silk market due to standardized production of silk. Standardization, especially in silkworm egg cultivation, yielded more consistency in quality, particularly important for mechanized silk weaving.[163] Since the new sectors of the economy could not be heavily taxed, the costs of industrialisation and necessary investments in modernization heavily fell on the peasant farmers, who paid extremely high land tax rates (about 30 percent of harvests) as compared to the rest of the world (double to seven times of European countries by net agricultural output). In contrast, land tax rates were about 2% in Qing China. The high taxation gave the Meiji government considerable leeway to invest in new initiatives.[164]

During the Meiji period, powers such as Europe and the United States helped transform Japan and made them realise a change needed to take place. Some leaders went out to foreign lands and used the knowledge and government writings to help shape and form a more influential government within their walls that allowed for things such as production. Despite the help Japan received from other powers, one of the key factors in Japan's industrializing success was its relative lack of resources, which made it unattractive to Western imperialism.[165] The farmer and the samurai classification were the base and soon the problem of why there was a limit of growth within the nation's industrial work. The government sent officials such as the samurai to monitor the work that was being done. Because of Japan's leaders taking control and adapting Western techniques it has remained one of the world's largest industrial nations.

The rapid industrialisation and modernization of Japan both allowed and required a massive increase in production and infrastructure. Japan built industries such as shipyards, iron smelters, and spinning mills, which were then sold to well-connected entrepreneurs. Consequently, domestic companies became consumers of Western technology and applied it to produce items that would be sold cheaply in the international market. With this, industrial zones grew enormously, and there was a massive migration to industrializing centres from the countryside. industrialisation additionally went hand in hand with the development of a national railway system and modern communications.[166]

| Year(s) | Production | Exports |

|---|---|---|

| 1868–1872 | 1026 | 646 |

| 1883 | 1682 | 1347 |

| 1889–1893 | 4098 | 2444 |

| 1899–1903 | 7103 | 4098 |

| 1909–1914 | 12460 | 9462 |

With industrialisation came the demand for coal. There was dramatic rise in production, as shown in the table below.

| Year | In millions of metric tons

|

In millions of long tons |

In millions of short tons |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1875 | 0.6 | 0.59 | 0.66 |

| 1885 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| 1895 | 5 | 4.9 | 5.5 |

| 1905 | 13 | 13 | 14 |

| 1913 | 21.3 | 21.0 | 23.5 |

Coal was needed for steamships and railroads. The growth of these sectors is shown below.

| Year | Number of steamships |

|---|---|

| 1873 | 26 |

| 1894 | 169 |

| 1904 | 797 |

| 1913 | 1,514 |

| Year | mi | km

|

|---|---|---|

| 1872 | 18 | 29 |

| 1883 | 240 | 390 |

| 1887 | 640 | 1,030 |

| 1894 | 2,100 | 3,400 |

| 1904 | 4,700 | 7,600 |

| 1914 | 7,100 | 11,400 |

Destruction of cultural heritage

The majority of

During the Meiji restoration's shinbutsu bunri, tens of thousands of Japanese Buddhist religious idols and temples were smashed and destroyed.[168] Japan then closed and shut down tens of thousands of traditional old Shinto shrines in the Shrine Consolidation Policy and the Meiji government built the new modern 15 shrines of the Kenmu restoration as a political move to link the Meiji restoration to the Kenmu restoration for their new State Shinto cult.

Outlawing of traditional practices

In the blood tax riots, the Meiji government put down revolts by Japanese samurai angry that the traditional untouchable status of burakumin was legally revoked.

Under the Meiji Restoration, the practices of the samurai classes, deemed feudal and unsuitable for modern times following the end of

During the Meiji Restoration, the practice of cremation and Buddhism were condemned and the Japanese government tried to ban cremation but were unsuccessful, then tried to limit it in urban areas. The Japanese government reversed its ban on cremation and pro-cremation Japanese adopted western European arguments on how cremation was good for limiting disease spread, so the Japanese government lifted their attempted ban in May 1875 and promoted cremation for diseased people in 1897.[170]

Use of foreign specialists

Even before the Meiji Restoration, the Tokugawa shogunate government hired German diplomat

Despite the value they provided in the modernization of Japan, the Japanese government did not consider it prudent for them to settle in Japan permanently. After their contracts ended, most of them returned to their country except some, like Josiah Conder and W. K. Burton.

Legacy

In popular culture

See also

- Datsu-A Ron

- Four Hitokiri of the Bakumatsu

- Land Tax Reform (Japan 1873)

- Japanese military modernization of 1868–1931

- Meiji Constitution

- Ōka shugi

Explanatory notes

- ^ Although the political system was consolidated under the Emperor, power was mainly transferred to a group of people, known as the Meiji oligarchy (and Genrō).[1]

- ^ tōyō dōtoku, seiyō gakugei, 東洋道徳西洋学芸

- Choshu domain found itself with spiralling debt.[23]

- ^ Although Aizawa wrote the Shinron in 1825, the text was not published until 1857.[51]

- ^ The five ports were Ōsaka, Yokohama, Nagasaki, Niigata, and Kōbe.

- ^ ōsei fukko, 王政復古

- ^ The authenticity of the rescript's provenance has been contested.[133]

- ^ At that time, the new government used the phrase "Itten-banjō" (一天万乗). However, the more generic term 天下 is most commonly used in modern historiography.

References

- ^ ISBN 9780198027089.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 22.

- ^ Jansen 1994, p. 3.

- ^ Jansen 1994, p. 6.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 17–22.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 24, 27.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 15–17.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 38.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 61–63.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 79.

- ^ a b Beasley 1972, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Jansen 1994, p. 52.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Jansen 1994, p. 53.

- ^ a b c Beasley 1972, pp. 80–82.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 86.

- ^ Jansen 2000, p. 288.

- ^ Jansen 2000, p. 247-248.

- ^ a b Jansen 2000, p. 251.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 51, 53.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 65.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 31–34.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b Jansen 2000, p. 257.

- ^ Jansen 1994, p. 8.

- ^ Jansen 2000, pp. 260–262.

- ^ a b Jansen 2000, pp. 264–265.

- ^ a b Beasley 1972, p. 77.

- ^ Jansen 2000, pp. 265–266.

- ^ Jansen 2000, p. 267.

- ^ Jansen 2000, p. 270.

- ^ a b Beasley 1972, p. 78.

- ^ Jansen 2000, p. 271.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 81.

- ^ Jansen 2000, p. 274.

- ^ a b Beasley 1972, p. 88.

- ^ a b Jansen 2000, pp. 274–275.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 89.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 90–92.

- ^ Hunt 2016, pp. 712–713.

- ^ Jansen 2000, pp. 278.

- ^ Jansen 2000, pp. 278–279.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 96–96.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 118.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Jansen 1994, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Jansen 2000, p. 283.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 99.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 100.

- ^ Jansen 1994, p. 58.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 99, 123.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 104.

- ^ Jansen 2000, pp. 283–284.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 98.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 112–114.

- ^ Jansen 2000, pp. 284–285.

- ^ a b Beasley 1972, p. 114.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 115.

- ^ Jansen 2000, p. 285.

- ^ Jansen 2000, pp. 285–286.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 120.

- ^ Jansen 2000, p. 174, 177.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 147.

- ^ Jansen 1994, p. 99.

- ^ Jansen 1994, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Jansen 2000, p. 293.

- ^ Jansen 2000, p. 295.

- ^ Jansen 1994, p. 106.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 157.

- ^ Jansen 1994, p. 117.

- ^ Jansen 1994, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Jansen 1994, pp. 130, 137–138.

- ^ a b Beasley 1972, p. 187.

- ^ Jansen 1994, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 183.

- ^ Jansen 1994, p. 129.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 190, 194.

- ^ Jansen 2000, p. 314.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 198.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Jansen 1994, pp. 163, 166–167.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Jansen 2000, p. 315.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 226.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 218.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 223.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 224.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 226–229.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 229–230.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 231–232.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 250.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 232.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 233.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 238–239.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Jansen 1994, p. 185.

- ^ Jansen 1994, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Jansen 1994, p. 217.

- ^ Jansen 1994, p. 221.

- ^ a b Jansen 1994, p. 213.

- ^ a b Beasley 1972, p. 257.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 258.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 260–262.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 262.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 286.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 262–263.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 266.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 271–272.

- ^ Jansen 1994, p. 292.

- ^ Jansen 1994, p. 296.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 276–277.

- ^ a b Jansen 2000, p. 310.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 277.

- ^ Jansen 1994, p. 295.

- ^ Jansen 1994, p. 297.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 279.

- ^ a b Jansen 1994, p. 331.

- ^ a b Jansen 2000, p. 311.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 281.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 288.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 283.

- ^ Jansen 1994, pp. 332–333.

- ^ Jansen 1994, pp. 335–336.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 290.

- ^ Jansen 2000, pp. 331–332.

- ^ a b Jansen 1994, p. 333.

- ^ a b Beasley 1972, p. 291.

- ^ Jansen 2000, p. 334.

- ISBN 978-1-933330-16-7.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 292–293.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 294.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 295.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Jansen 2000, p. 312.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 296.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 296–297.

- ^ a b Beasley 1972, p. 297.

- ^ Keene 2002, p. 131.

- ^ Keene 2002, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Beasley 1972, pp. 297–298.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 298.

- ^ David "Race" Bannon, "Redefining Traditional Feudal Ethics in Japan during the Meiji Restoration," Asian Pacific Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 1 (1994): 27–35.

- ISBN 978-1-59420-271-1.

- ^ Federal Research Division (1992). Japan: A Country Study. Library of Congress. p. 38.

- ISBN 978-0190932947. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Bestor, Theodore C. "Japan." Countries and Their Cultures. Eds. Melvin Ember and Carol Ember. Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2001. 1140–1158. 4 vols. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Gale. Pepperdine University SCELC. 23 November 2009 [1].

- JSTOR 23462195.

- ^ "The Meiji Restoration and Modernization | Asia for Educators | Columbia University". afe.easia.columbia.edu. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-429-51012-0.

- JSTOR 3113976.

- ISBN 9781350121683.

- ^ Zimmermann, Erich W. (1951). World Resources and Industries. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 462, 525, 718.

- S2CID 154563371.

- ^ "Japanese castles History of Castles". Japan Guide. 4 September 2021.

- ^ "Shinbutsu bunri – the separation of Shinto and Buddhism". Japan Reference. 11 July 2019.

- ISBN 978-0691176475.

In 1871 the Dampatsurei edict forced all samurai to cut off their topknots, a traditional source of identity and pride.

- ^ Hiatt, Anna (9 September 2015). "The History of Cremation in Japan". Jstor Daily.

- ^ Jansen 2000, p. 323.

- ^ Prince 1991, pp. 220–222.

- ^ Eisenbeis, Richard (18 June 2021). "Rurouni Kenshin: The Beginning — Live Action Film Review". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on 10 December 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2025.

Bibliography

Books and articles

- ISBN 978-0-8047-0815-9.

- Hunt, Lynn (2016). The Making of the West: Peoples and Cultures. Boston: Macmillan. pp. 712–713. ISBN 978-1-4576-8143-1.

- ISBN 978-0-231-10173-8.

- ISBN 978-0-674-00334-7.

- Keene, Donald (2002). Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852-1912. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12341-9.

- ISBN 9780691010465.

Further reading

- Akamatsu, Paul (1972). Meiji, 1868: Revolution and Counter-revolution in Japan. Great revolutions (1st U.S. ed.). New York: ISBN 978-0-06-010044-5.

- ISBN 978-0-312-23373-0.

- JSTOR 2385417.

- )

- Earl, David Magarey (1981). Emperor and Nation in Japan: Political Thinkers of the Tokugawa Period. Westport, Conn: ISBN 978-0-313-23105-6.

- ISBN 978-0-520-01566-1.

- ISBN 978-1-4008-5430-1.

- ISBN 978-0-521-22356-0.

- Karube, Tadashi; OCLC 1091359003.

- McAleavy, Henry (September 1958). "The Meiji Restoration". History Today. Vol. 8, no. 9. pp. 634–645.

- McAleavy, Henry (May 1959). "The Making of Modern Japan". History Today. Vol. 9, no. 5. pp. 297–300.

- ISBN 978-0-321-07801-8.

- ISBN 978-1-933330-16-7.

- Strayer, Robert W.; ISBN 978-1-319-02272-3.

- ISBN 978-0-226-56803-4.

- JSTOR 2384397.

- Wall, Rachel F. (1971). Japan's Century: An Interpretation of Japanese History Since the Eighteen-fifties. London: Historical Association. ISBN 978-0-85278-044-2.

External links

- Essay on The Meiji Restoration Era, 1868–1889 on the About Japan, A Teacher's Resource website

- A rare collection of Japanese Photographs of the Meiji Restoration from famous 19th-century Japanese and European photographers