Chlamydia trachomatis

| Chlamydia trachomatis | |

|---|---|

| |

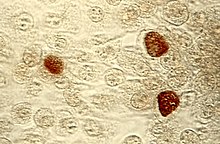

| Chlamydia trachomatis in brown | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Chlamydiota |

| Class: | Chlamydiia |

| Order: | Chlamydiales |

| Family: | Chlamydiaceae |

| Genus: | Chlamydia |

| Species: | C. trachomatis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Chlamydia trachomatis (Busacca 1935) Rake 1957 emend. Everett et al. 1999[1]

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Chlamydia trachomatis (

Different types of C. trachomatis cause different diseases. The most common strains cause disease in the genital tract, while other strains cause disease in the eye or lymph nodes. Like other Chlamydia species, the C. trachomatis life cycle consists of two morphologically distinct life stages: elementary bodies and reticulate bodies. Elementary bodies are spore-like and infectious, whereas reticulate bodies are in the replicative stage and are seen only within host cells.

Description

Chlamydia trachomatis is a

The C. trachomatis genome is substantially smaller than that of many other bacteria at approximately 1.04

Life cycle

Like other Chlamydia species, C. trachomatis has a life cycle consisting of two morphologically distinct forms. First, C. trachomatis attaches to a new host cell as a small spore-like form called the elementary body.[5] The elementary body enters the host cell, surrounded by a host vacuole, called an inclusion.[5] Within the inclusion, C. trachomatis transforms into a larger, more metabolically active form called the reticulate body.[5] The reticulate body substantially modifies the inclusion, making it a more hospitable environment for rapid replication of the bacteria, which occurs over the following 30 to 72 hours.[5] The massive number of intracellular bacteria then transition back to resistant elementary bodies, before causing the cell to rupture and being released into the environment.[5] These new elementary bodies are then shed in the semen or released from epithelial cells of the female genital tract, and attach to new host cells.[6]

Classification

C. trachomatis are bacteria in the genus Chlamydia, a group of obligate intracellular parasites of eukaryotic cells.[3] Chlamydial cells cannot carry out energy metabolism and they lack biosynthetic pathways.[7]

C. trachomatis strains are generally divided into three

C. trachomatis is thought to have diverged from other Chlamydia species around 6 million years ago. This genus contains a total of nine species: C. trachomatis,

|

Strains that cause lymphogranuloma venereum (Serovars L1 to L3) | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Role in disease

Clinical signs and symptoms of C. trachomatis infection in the genitalia present as the chlamydia infection, which may be asymptomatic or may resemble a gonorrhea infection.[9] Both are common causes of multiple other conditions including pelvic inflammatory disease and urethritis.[10]

C. trachomatis is the single most important infectious agent associated with blindness (trachoma), and it also affects the eyes in the form of inclusion conjunctivitis and is responsible for about 19% of adult cases of conjunctivitis.[11]

C. trachomatis in the lungs presents as the chlamydia pneumoniae respiratory infection and can affect all ages.[12]

Pathogenesis

Elementary bodies are generally present in the semen of infected men and vaginal secretions of infected women.

Presentation

Most people infected with C. trachomatis are asymptomatic. However, the bacteria can present in one of three ways: genitourinary (genitals), pulmonary (lungs), and ocular (eyes).[13]

Genitourinary cases can include genital discharge, vaginal bleeding, itchiness (pruritus), painful urination (dysuria), among other symptoms.[14] Often, symptoms are similar to those of a urinary tract infection.[citation needed]

When C. trachomatis presents in the eye in the form of trachoma it begins by gradually thickening the eyelids, and eventually begins to pull the eyelashes into the eyelid.[15] In the form of inclusion conjunctivitis the infection presents with redness, swelling, mucopurulent discharge from the eye, and most other symptoms associated with adult conjunctivitis.[11]

When C. trachomatis is in the lungs in the form of a respiratory infection it typically has symptoms of a runny or stuffy nose, low-grade fever, hoarseness of voice, as well as other symptoms associated with general pneumonia.[16]

C. trachomatis may latently infect the chorionic villi tissues of pregnant women, thereby impacting pregnancy outcome.[17]

Prevalence

Three times as many women are diagnosed with genitourinary C. trachomatis infections as men. Women aged 15–19 have the highest prevalence, followed by women aged 20–24, although the rate of increase of diagnosis is greater for men than for women. Risk factors for genitourinary infections include unprotected sex with multiple partners, lack of condom use, and low socioeconomic status living in urban areas.[13]

Pulmonary infections can occur in infants born to women with active chlamydia infections, although the rate of infection is less than 10%.[14]

Ocular infections take the form of inclusion conjunctivitis or trachoma, both in adults and children. About 84 million worldwide develop C. trachomatis eye infections and 8 million are blinded as a result of the infection.

Treatment

Treatment depends on the infection site, age of the patient, and whether another infection is present. Having a C. trachomatis and one or more other sexually transmitted infections at the same time is possible. Treatment is often done with both partners simultaneously to prevent reinfection. C. trachomatis may be treated with several antibiotic medications, including azithromycin, erythromycin, ofloxacin,[9] and tetracycline.

Tetracycline is the most preferred antibiotic to treat C.trachomatis and has the highest success rate. Azithromycin and doxycycline have equal efficacy to treat C. trachomatis with 97 and 98 percent success, respectively. Azithromycin is dosed as a 1 gram tablet that is taken by mouth as a single dose, primarily to help with concerns of non-adherence.[20] Treatment with generic doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 7 days has equal success with expensive delayed-release doxycycline 200 mg once a day for 7 days.[20] Erythromycin is less preferred as it may cause gastrointestinal side effects, which can lead to non-adherence. Levofloxacin and ofloxacin are generally no better than azithromycin or doxycycline and are more expensive.[20]

If treatment is necessary during pregnancy, levofloxacin, ofloxacin, tetracycline, and doxycycline are not prescribed. In the case of a patient who is pregnant, the medications typically prescribed are azithromycin, amoxicillin, and erythromycin. Azithromycin is the recommended medication and is taken as a 1 gram tablet taken by mouth as a single dose.[20] Despite amoxicillin having fewer side effects than the other medications for treating antenatal C. trachomatis infection, there have been concerns that pregnant women who take penicillin-class antibiotics can develop a chronic persistent chlamydia infection.[21] Tetracycline is not used because some children and even adults can not withstand the drug, causing harm to the mother and fetus.[20] Retesting during pregnancy can be performed three weeks after treatment. If the risk of reinfection is high, screening can be repeated throughout pregnancy.[9]

If the infection has progressed, ascending the reproductive tract and pelvic inflammatory disease develops, damage to the fallopian tubes may have already occurred. In most cases, the C. trachomatis infection is then treated on an outpatient basis with azithromycin or doxycycline. Treating the mother of an infant with C. trachomatis of the eye, which can evolve into pneumonia, is recommended.

There have been a few reported cases of C.trachomatis strains that were resistant to multiple antibiotic treatments. However, as of 2018, this is not a major cause of concern as antibiotic resistance is rare in C.trachomatis compared to other infectious bacteria.[22]

Laboratory tests

Chlamydia species are readily identified and distinguished from other Chlamydia species using DNA-based tests. Tests for Chlamydia can be ordered from a doctor, a lab or online.[23]

Most strains of C. trachomatis are recognized by

- Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) tests find the genetic material (DNA) of Chlamydia bacteria. These tests are the most sensitive tests available, meaning they are very accurate and are very unlikely to have false-negative test results. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test is an example of a nucleic acid amplification test. This test can also be done on a urine sample, urethral swabs in men, or cervical or vaginal swabs in women.[25]

- Nucleic acid hybridization tests (DNA probe test) also find Chlamydia DNA. A probe test is very accurate but is not as sensitive as NAATs.

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, EIA) finds substances (Chlamydia antigens) that trigger the immune system to fight Chlamydia infection. Chlamydia Elementary body (EB)-ELISA could be used to stratify different stages of infection based upon Immunoglobulin-γ status of the infected individuals [26]

- Direct fluorescent antibody test also finds Chlamydia antigens.

- Chlamydia cell culture is a test in which the suspected Chlamydia sample is grown in a vial of cells. The pathogen infects the cells, and after a set incubation time (48 hours), the vials are stained and viewed on a fluorescent light microscope. Cell culture is more expensive and takes longer (two days) than the other tests. The culture must be grown in a laboratory.[27]

Research

Due to its significance to human health, C. trachomatis is the subject of research in laboratories around the world. The bacteria are commonly grown in

Other research has been conducted towards the creation of a vaccine against C. trachomatis, finding that it would be very difficult to create a fully effective or even partially effective vaccine since the host's response to infection involves complex immunological pathways that must first be fully understood to ensure that adverse effects are avoided.[28]

Vaccine

In August 2016 a Phase I, double-blind, parallel, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial was undertaken by the Danish Statens Serum Institut at Hammersmith Hospital in London, UK, in healthy women aged 19–45 years. The trial aimed to assess the safety and ability to provoke an immune response of the CTH522 chlamydia vaccine. 35 women not infected with chlamydia were included in the trial. The trial included two adjuvants and a saline control group. The vaccine was found to be safe, and all women who received the vaccine regardless of adjuvant developed an immune response against chlamydia.[29]

The Serum Institute has announced that it will continue to pursue funding to move the vaccine into a Phase II trial.[30]

History

C. trachomatis was first described in 1907 by Stanislaus von Prowazek and Ludwig Halberstädter in scrapings from trachoma cases.

C. trachomatis agent was first cultured and isolated in the yolk sacs of eggs by

Evolution

In the 1990s it was shown that there are several species of Chlamydia. Chlamydia trachomatis was first described in historical records in Ebers papyrus written between 1553 and 1550 BC.[39] In the ancient world, it was known as the blinding disease trachoma. The disease may have been closely linked with humans and likely predated civilization.[40] It is now known that C. trachomatis comprises 19 serovars which are identified by monoclonal antibodies that react to epitopes on the major outer-membrane protein (MOMP).[41] Comparison of amino acid sequences reveals that MOMP contains four variable segments: S1,2 ,3 and 4. Different variants of the gene that encodes for MOMP, differentiate the genotypes of the different serovars. The antigenic relatedness of the serovars reflects the homology levels of DNA between MOMP genes, especially within these segments.[42]

Furthermore, there have been over 220 Chlamydia vaccine trials done on mice and other non-human host species to target C. muridarum and C. trachomatis strains. However, it has been difficult to translate these results to the human species due to physiological and anatomical differences. Future trials are working with closely related species to the human.[43]

See also

References

- ^ J.P. Euzéby. "Chlamydia". List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ^ "Chlamydia trachomatis". Retrieved 2015-11-18.[dead link]

- ^ PMID 27108705.

- ^ ISBN 9781118960608.

- ^ PMID 24509351.

- ^ PMID 28835360.

- ^ Becker, Y. (1996). Molecular evolution of viruses: Past and present (4th ed.). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8091/.

- ^ Burton, Matthew J.; Trachoma: an overview, British Medical Bulletin, Volume 84, Issue 1, 1 December 2007, Pages 99–116, https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldm034

- ^ PMID 24135174.

- S2CID 25249521.

- ^ PMID 2154106.

- PMID 32809709, retrieved 2022-06-26

- ^ a b "Chlamydial Infections". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ PMID 23316985.

- PMID 30698042.

- ^ "Recommendations for the Prevention and Management of Chlamydia trachomatis Infections, 1993". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-05.

- PMID 30078192.

- ^ "Trachoma". Prevention of Blindness and Visual Impairment. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on January 28, 2011.

- ^ Global Network for Neglected Tropical Diseases. Trachoma interactive fact sheet. http://old.globalnetwork.org/sites/all/modules/globalnetwork/factsheetxml/disease.php?id=9 Accessed February 6, 2011,

- ^ a b c d e f "Chlamydial Infections in Adolescents and Adults". Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- PMID 1318677.

- S2CID 11631854.

- ^ "Oral Chlamydia Home Testing, Symptoms and Treatment | myLAB Box™". 2019-04-03.

- PMID 10678996.

- PMID 27007215.

- PMID 28444306.

- ^ "Chlamydia Tests". Sexual Conditions Health Center. WebMD. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- PMID 24696438.

- S2CID 201019235.

- ^ Follmann, Frank (2020-01-28). "A chlamydia vaccine is on the horizon". Archived from the original on 2021-09-12. Retrieved 2021-05-18.

- PMID 31536549.

- ^ Fox, A., Rogers, J. C., Gilbart, J., Morgan, S., Davis, C. H., Knight, S., & Wyrick, P. B. (1990). Muramic acid is not detectable in Chlamydia psittaci or Chlamydia trachomatis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Infection and immunity, 58(3), 835–7.

- PMID 26290580.

- PMID 24336210.

- ^ "Chlamydial Infections". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ PMID 4651177.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 5388815.

- PMID 13502539.

- S2CID 5388815.

- PMID 15078842.

- PMID 18325260.

- PMID 1702141.

- PMID 30766521.

Further reading

- Bellaminutti, Serena; Seracini, Silva; De Seta, Francesco; Gheit, Tarik; Tommasino, Massimo; Comar, Manola (November 2014). "HPV and Chlamydia trachomatis Co-Detection in Young Asymptomatic Women from High Incidence Area for Cervical Cancer". Journal of Medical Virology. 86 (11): 1920–1925. S2CID 29787203.