Chlamydiota

| Chlamydiota | |

|---|---|

| |

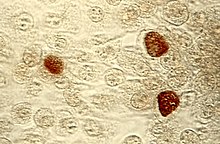

| Chlamydia trachomatis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Superphylum: | PVC superphylum |

| Phylum: | Chlamydiota Garrity & Holt 2021[3] |

| Class: | Chlamydiia Horn 2016[1][2] |

| Orders and families | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Chlamydiota (synonym Chlamydiae) are a

Among the Chlamydiota, all of the ones long known to science grow only by infecting

These Chlamydiota can grow only where their host cells grow, and develop according to a characteristic biphasic developmental cycle.[12][13][14] Therefore, clinically relevant Chlamydiota cannot be propagated in bacterial culture media in the clinical laboratory. They are most successfully isolated while still inside their host cells.

Of various Chlamydiota that cause human disease, the two most important species are Chlamydia pneumoniae, which causes a type of pneumonia, and Chlamydia trachomatis, which causes chlamydia. Chlamydia is the most common bacterial sexually transmitted infection in the United States, and 2.86 million chlamydia infections are reported annually.

History

Chlamydia-like disease affecting the eyes of people was first described in ancient Chinese and Egyptian manuscripts. A modern description of chlamydia-like organisms was provided by Halberstaedrrter and von Prowazek in 1907.

Chlamydial isolates cultured in the yolk sacs of embryonating eggs were obtained from a human

Nomenclature

In 1966, Chlamydiota were recognized as bacteria and the genus

Taxonomy and molecular signatures

The Chlamydiota currently contain eight validly named genera, and 14 genera.

The Chlamydiales order as recently described contains the families Chlamydiaceae, and the Clavichlamydiaceae, while the new Parachlamydiales order harbors the remaining seven families.[17] This proposal is supported by the observation of two distinct phylogenetic clades that warrant taxonomic ranks above the family level. Molecular signatures in the form of conserved indels (CSIs) and proteins (CSPs) have been found to be uniquely shared by each separate order, providing a means of distinguishing each clade from the other and supporting the view of shared ancestry of the families within each order.[17][28] The distinctness of the two orders is also supported by the fact that no CSIs were found among any other combination of families.

Molecular signatures have also been found that are exclusive for the family Chlamydiaceae.[17][28] The Chlamydiaceae originally consisted of one genus, Chlamydia, but in 1999 was split into two genera, Chlamydophila and Chlamydia. The genera have since 2015 been reunited where species belonging to the genus Chlamydophila have been reclassified as Chlamydia species.[29][30]

However, CSIs and CSPs have been found specifically for Chlamydophila species, supporting their distinctness from Chlamydia, perhaps warranting additional consideration of two separate groupings within the family.[17][28] CSIs and CSPs have also been found that are exclusively shared by all Chlamydia that are further indicative of a lineage independent from Chlamydophila, supporting a means to distinguish Chlamydia species from neighbouring Chlamydophila members.

Phylogenetics

The Chlamydiota form a unique bacterial evolutionary group that separated from other bacteria about a billion years ago, and can be distinguished by the presence of several CSIs and CSPs.[17][28][31][14] The species from this group can be distinguished from all other bacteria by the presence of conserved indels in a number of proteins and by large numbers of signature proteins that are uniquely present in different Chlamydiae species.[32][33]

Reports have varied as to whether the Chlamydiota are related to the

Human pathogens and diagnostics

Three species of Chlamydiota that commonly infect humans are described:

- chlamydia

- Chlamydophila pneumoniae, which causes a form of pneumonia

- Chlamydophila psittaci, which causes psittacosis

The unique physiological status of the Chlamydiota including their biphasic lifecycle and obligation to replicate within a eukaryotic host has enabled the use of DNA analysis for chlamydial diagnostics.

Phylogeny

| 16S rRNA based | 120 marker proteins based GTDB 08-RS214[41][42][43] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Taxonomy

The currently accepted taxonomy is based on the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN)[44] and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)[45]

- "Similichlamydiales" Pallen, Rodriguez-R & Alikhan 2022 [Hat2]

- Family "Piscichlamydiaceae" Horn 2010

- Family "Parilichlamydiaceae" Stride et al. 2013 ["Similichlamydiaceae" Pallen, Rodriguez-R & Alikhan 2022]

- Order Chlamydiales Storz & Page 1971

- Family "Actinochlamydiaceae" Steigen et al. 2013

- Family "Criblamydiaceae" Thomas, Casson & Greub 2006

- Family Chlamydiaceae Rake 1957 ["Clavichlamydiaceae" Horn 2011]

- Family Parachlamydiaceae Everett, Bush & Andersen 1999

- Family RhabdochlamydiaceaeCorsaro et al. 2009

- Family Simkaniaceae Everett, Bush & Andersen 1999

- Family WaddliaceaeRurangirwa et al. 1999

See also

References

- ISBN 978-0-387-95042-6.

- PMID 27530111.

- ^ S2CID 239887308.

- PMID 23950718.

- ^ S2CID 212423997.

- PMID 24292151.

- PMID 25670734.

- PMID 24135174.

- PMID 24336210.

- PMID 27144308.

- PMID 21717204.

- S2CID 13405815.

- PMID 16043254.

- ^ S2CID 39036549.

- ISBN 9780387098425.

- PMID 5330228.

- ^ S2CID 17099157.

- ^ PMID 27530111.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-387-98771-2.

- ^ PMID 16014485.

- ^ Sayers; et al. "Chlamydiia". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) taxonomy database. Retrieved 2016-10-24.

- PMID 10319462.

- PMID 10319478.

- S2CID 31211875.

- PMID 23275507.

- ^ Kuo C-C, Horn M, Stephens RS (2011) Order I. Chlamydiales. In: Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, vol. 4, 2nd ed. pp. 844-845. Eds Krieg N, Staley J, Brown D, Hedlund B, Paster B, Ward N, Ludwig W, Whitman W. Springer-: New York.

- ^ PMID 16436211.

- PMID 25618261.

- PMID 28056215.

- PMID 12957942.

- PMID 16079343.

- PMID 17049238.

- PMID 11155969.

- PMID 15143026.

- S2CID 2094762.

- PMID 16614250.

- ^ "The LTP". Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "LTP_all tree in newick format". Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "LTP_08_2023 Release Notes" (PDF). Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "GTDB release 08-RS214". Genome Taxonomy Database. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ "bac120_r214.sp_label". Genome Taxonomy Database. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ "Taxon History". Genome Taxonomy Database. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ J.P. Euzéby. "Chlamydiota". List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN). Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- ^ Sayers; et al. "Chlamydiae". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) taxonomy database. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

External links

- Ward M. "www.chlamydiae.com". University of Southampton.

The comprehensive reference and education wiki on Chlamydia and the Chlamydiales

- Chlamydia Overview