Comet Kohoutek

Perihelion 0.1424249 AU[5] | | |

| Eccentricity | 0.999997 (inbound) 0.99992 (outbound)[4] | |

|---|---|---|

| ≈11 million yr (inbound) ≈ 80 thousand yr (outbound)[4] | ||

| Inclination | 14.30426° | |

| 258.48953° | ||

| 28 December 1973[5][6] | ||

| 37.79761° | ||

| Earth MOID | 0.029043 AU (4.34 million km)[6] | |

| Physical characteristics | ||

Mean diameter | 4.2 km (2.6 mi)[7] | |

| Albedo | 0.67[7][b] | |

| –3 (1973 perihelion) 0 (peak for ground observers)[8] | ||

| 5.8 (total) 9.5 (nucleus) | ||

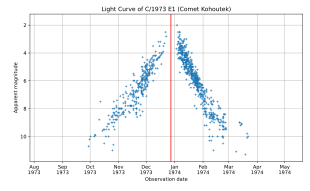

Comet Kohoutek (formally designated C/1973 E1 and formerly as 1973 XII and 1973f)[c] is a comet that passed close to the Sun towards the end of 1973. Early predictions of the comet's peak brightness suggested that it had the potential to become one of the brightest comets of the 20th century, capturing the attention of the wider public and the press and earning the comet the moniker of "Comet of the Century". Although Kohoutek became rather bright, the comet was ultimately far dimmer than the optimistic projections: its apparent magnitude peaked at only –3 (as opposed to predictions of roughly magnitude –10) and it was visible for only a short period, quickly dimming below naked-eye visibility by the end of January 1974.[d]

The comet was discovered by and named after

Because of its early detection and unique characteristics, numerous scientific assets were dedicated to observing Kohoutek during its 1973–74 traversal of the

Kohoutek's highly

Discovery

The comet was discovered on 18 March 1973 by Czech astronomer

The comet's discovery was serendipitous: beginning in 1971, Kohoutek had been searching for

Orbit

Both the Minor Planet Center and the JPL Small-Body Database list Kohoutek as having a hyperbolic trajectory when it was near perihelion,[5][6] but the orbit became bound to the Sun by 1978.[27] The comet is not expected to return for about 75,000 years.[4] Some of the meteoroids ejected by Kohoutek during its initial approach, particularly those with diameters no smaller than 0.2 mm (0.0079 in), were placed into stable orbits around the Sun.[28]

As seen from Earth between 1973 and 1974, the comet took a southeastward path across the sky similar to

Structure and composition

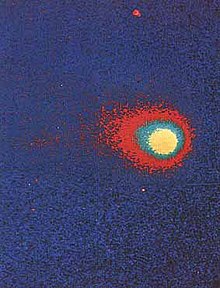

Kohoutek's highly eccentric orbit and possible lack of prior planetary or solar interactions suggest that the comet may have been a primordial body of either the Solar System or that it may have originated from another planetary system.[23] The comet may have also originated from the Oort cloud.[19] A 1976 analysis of photometry and water loss rates estimated that the nucleus had a radius of around 2.1 km (1.3 mi) and an albedo of around 0.67.[7] A photometric analysis of Kohoutek, using Mercury as a reference, established an upper limit of 30 km (19 mi) for the diameter of Kohoutek's nucleus.[30] An attempt to detect a radar echo from Kohoutek's nucleus using the Haystack Radio Telescope received no radar returns, constraining the nucleus's size to under 250 km (160 mi).[31] The comet has a total absolute magnitude (at 1 AU) of 5.8 and a nuclear absolute magnitude of 9.5.[6] During Kohoutek's 1973–74 apparition, its tail's width ranged from around 30,000 km (19,000 mi) near the coma to 300,000 km (190,000 mi) farther away. Detection of positive carbon monoxide ions showed that the tail was at least 20 million km (12 million mi) in length.[32] A more yellow and orange appearance of the dust tail of Kohoutek during its perihelion – as observed by astronauts on Skylab – was likely the result of light scattering by basaltic dust particles with sizes of around 0.5 μm. The tail lacked color closer to the coma near perihelion, indicating a large distribution of particle sizes and resulting in a white appearance.[33] Observations from the Joint Observatory for Cometary Research in Socorro, New Mexico, were able to trace the blue ion tail of Kohoutek – featuring more prominently than the comet's dust tail – to a distance of 0.333 AU (49,800,000 km; 31,000,000 mi) away from the nucleus.[34] The particle density within the tail several million miles away from the nucleus was about 10 ions per cubic centimeter, while the maximum electron density within the tail was around 20,000 electrons per cubic centimeter.[32][35] At a distance of around 0.5 AU from the Sun, the plasma outflow in Kohoutek's tail generated a weak magnetic field with a strength comparable to the interplanetary magnetic field.[36]

Analyses of Kohoutek have provided different assessments of the scale of the comet's release of dust and gas, with some suggesting that Kohoutek is relatively dust-rich (and consequently gas-poor) and others suggesting that the comet is relatively dust-poor (and consequently gas-rich).

Later

2O+

), particularly in the comet's tail.[48][49] This chemical species was most likely the result of the photoionization of neutral water (H

2O) very near the nucleus.[50][51]

Observational history

Following Luboš Kohoutek's discovery of his eponymous comet, additional photographic observations taken on 30 March and 2 April 1973 showed that the comet's coma was highly condensed and 20 arcseconds in diameter. The comet was last observed by Kohoutek on 5 May 1973 before it became too faint and unremarkable to observe or discern against the glare of

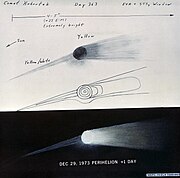

In November 1973, Kohoutek became bright enough to be visible to the naked eye.[13] The ion component of the comet's tail was first noted on 21 November accompanying the brighter dust component.[15] The comet brightened to an apparent magnitude of 2.8 by 22 December 1973 before becoming indiscernible to ground-based observers due to Kohoutek's conjunction with the Sun;[13] between 24 and 31 December the comet was within 10° of the Sun.[11] During this period, the comet experienced a surge in brightness that – although not clearly observable from the Earth's surface – placed it in the echelon of great comets.[66] Kohoutek was at its brightest during this period, becoming a roughly –3rd magnitude object.[11] Kohoutek was a much brighter object in the infrared, reaching magnitudes of at least –4.75 and –5.70 at wavelengths of 10 microns and 20 microns, respectively.[62] At its closest approach, the comet was visually separated by only around 0.75° from the center of the Sun.[15] While the comet was too close to the Sun to be discernible from the ground, astronauts on Skylab and Soyuz 13 were able to observe the comet during its perihelion.[64] The astronauts on Skylab noted that the comet was distinctly yellow and estimated that Kohoutek at its brightest was comparable to the magnitude –1.6 brightness of Jupiter.[11] An antitail emerged during Kohoutek's close passage, stretching as far as 5–7° from the comet towards the Sun.[15] The separate gas and dust tails typically seen on comets were not observed from Skylab; instead, the comet uniformly took on a yellow texture, transitioning to white and later to a mottled violet appearance.[67] The strikingly yellow color of the comet at perihelion was due to the scattering of sunlight by sodium released by the comet.[68]

I just finished taking the 233 photos and Kohoutek is not looking like our old, pretty, graceful-looking, blue-white comet any more. It's getting so close to the Sun now that the tail is fanning out; it's very short. I think I can't see the rest of the tail just because it's so light. But what I can see behind the comet now, the—the [coma] is getting quite large and bright, and the tail, all we can see is a fan behind it. And we're beginning to see some reds and some yellows in it.

—Gerald P. Carr, speaking to NASA Mission Control Center on 25 December 1973, Skylab Air-to-Ground Voice Transcription (Tape #MC1309/1)[69]

Kohoutek once again became observable to ground-based observers beginning on 27 December 1973. For ground observers, the comet was at most a 0th or 1st magnitude object.[11] By the time Kohoutek had reached a more favorable position for viewing by the general public, it had faded to around magnitude 2.[64] Although the comet was dimmer than anticipated, it was nonetheless among the ten brightest comets as seen from Earth between 1750 and 1994.[70] The comet rapidly dimmed following its perihelion on 28 December, diminishing to magnitude –1.5 on 1 January 1974 and reaching magnitude 4 by 10 January 1974. By the end of January 1974, Kohoutek was too faint to be seen with the unaided eye.[13] The comet dimmed to around 10th magnitude towards the end of March 1974, after which it became too faint to clearly detect against the backdrop of the zodiacal light.[11] Unlike on the comet's inbound trek, its appearance on the outbound trek was much more diffuse and nebulous.[71] When the comet returned to the same distance from the Sun at which it was discovered, it was over 100 times fainter than at its first detection.[22] The comet was last photographed in early November 1974 at a heliocentric distance of around 5 AU with an apparent magnitude of 22.[64] At its greatest visual extent, Kohoutek's tail was well-defined and spanned 25° in length.[13] In January 1974 its tail featured both a helical structure and a more irregular cloud-like structure about 0.1 AU away from the nucleus.[72] Kohoutek's antitail spanned as much as 3° for ground observers;[13] the antitail became more diffuse and dim following perihelion, making its visibility less favorable.[68] A faint meteor shower seen on 1–3 March 1974, concurrent with Earth's closest pass of Kohoutek's orbit, may have been directly associated with Kohoutek.[73]

Brightness predictions

Kohoutek's anticipated close passage of the Sun and its pristine condition – having likely never approached the Sun previously – made the comet a candidate for becoming one of the brightest comets of the 20th century. Conventional wisdom held that the brightness of a comet was

Although the most bullish predictions caught the attention of the press and the general public, some astronomers – like S. W. Milbourn and Whipple – were more uncertain and held that such predictions were optimistic.[11][19] Regardless of its luminosity, the comet would be too close to the sun to be seen by ground observers at its brightest.[74] British Astronomical Association (BAA) circular 548, published on 25 July 1973, provided an alternative prediction of magnitude –3 for Kohoutek's peak brightness.[11] Higher-end projections of Kohoutek's peak brightness remained as high as magnitude –10 into August 1973. An article in Nature published in the final week of September 1973 suggested that Kohoutek's peak brightness could have a greater than 50 percent chance of being within two magnitudes of –4.[25] The National Newsletter accompanying the Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada in October 1973 estimated that Kohoutek would remain visible to the naked eye for four months bracketing perihelion.[79] Brightness predictions were revised downward following the comet's behavior as perihelion approached.[16] On 11 October 1973, BAA circular 549 provided a revised estimate of magnitude –4 for Kohoutek's brightest apparent magnitude. While still bright, such a brightness would yield only around ten days of clear naked-eye visibility for observers in the Northern Hemisphere.[11] Publicized predictions of the comet were scaled back in November 1973.[80] Although Kohoutek brightened by a factor of nearly a million by perehelion, sufficiently "to be a fine object for experienced observers when seen under ideal conditions in clear skies away from city lights" according to Whipple, its peak magnitude of –3 fell short of the most publicized projections and proved mediocre to the public eye;[19][22] however, the comet's ultimate brightness was close to the published lower-end predictions.[11] Whipple later quipped that "if you want to have a safe gamble, bet on a horse – not a comet."[81]

Despite higher assumed values of n, the light curve of Kohoutek from 24 November 1973 to perihelion best fit n = 2.2 while its light curve after perihelion to 16 January 1974 best fit n = 3.3 or n = 3.8.[82] The more optimistic use of n = 6 led to overestimates of Kohoutek's perihelion brightness by as much as a factor of 2800.[83] The early brightness of Kohoutek around the time of its discovery may have been influenced by the intense outgassing of highly volatile substances; such volatiles may have been abundant in the nucleus if Kohoutek had never previously entered the inner Solar System.[75][84] The degree of outgassing may have been enhanced by extremely porous outer layers of the nucleus that readily allowed the most volatile ices to vaporize at great distances from the Sun.[85] In this model, the comet would have brightened quickly in the early stages of its solar approach, at about n = 5.78, before brightening more in line with shorter period comets.[66][22] The early burst would have led to inflated expectations for the comet's ultimate brightness.[76] A separate study of long-period comets published in 1995 found that comets with initial semi-major axes greater than 10,000 AU brighten more slowly and less substantially before perihelion than shorter period comets.[10] Such comets are discovered at farther distances from the Sun than other comets as a result.[86] It is now understood that Kohoutek's light curve preceding its 1973 perihelion was typical for comets with similar orbits.[10]

Observing campaigns and scientific results

Kohoutek was the subject of intense scientific investigation and was observed over an unprecedentedly large range of the electromagnetic spectrum.[14] Kohoutek represented the first time radio astronomy techniques were used to study a comet.[19] The possibility that the comet could be entering the inner Solar System for the first time since its formation – making it potentially illustrative of the evolution of comets and conditions in the early Solar System – made it an attractive scientific target.[18]: 12 The comet's exceptionally early detection, as well as the concurrence of its perihelion with Skylab 4, allowed for and motivated the coordination of Operation Kohoutek, a cometary observing campaign backed by NASA and involving a wide array of instruments and observation platforms. The resulting study of Kohoutek was in its time the most comprehensive and detailed of any comet; the scale of the international effort to observe the comet would not be surpassed until the 1986 International Halley Watch for Halley's Comet.[23][75]

Of particular interest were the molecular makeup of the comet and the dust in its tail.

Skylab, the

The results of the observations conducted as part of Operation Kohoutek were presented in June 1974 at a workshop held at the Marshall Space Flight Center.[100] Comet science saw considerable advances as a result of the observational research conducted on Kohoutek,[75] ushering in what Fred Whipple termed a "'renaissance' of cometary research".[22] At the time, most scientists accepted Whipple's hypothesis that cometary nuclei were "dirty snowballs" made mostly of ices. However, there were other alternative models for comet nuclei, such as the "sand bank" model championed by British astronomer Raymond A. Lyttleton which considered nuclei as loose collections of dust particles with negligible amounts of ice.[101][3]: 5 The detection and identification of various gasses emanating from Kohoutek validated the predictions of Whipple's model.[89][102][103] Kohoutek's behavior led to the development of more detailed models seeking to explain the physical structure of comet nuclei.[47] One proposal suggested that Kohoutek belonged to a subset of comets containing a non-volatile dust mantle around an icy volatile core.[104] The occultation of the radio source PKS 2025–15 by Kohoutek's tail on 5 January 1974 also served as an opportunity to study interplanetary scintillation.[105][106]

Media coverage and viewing events

A hundred years from now, how will our great, great grandchildren remember 1973?

In a future age, when the names of Nixon and Brezhnev are dimly remembered, and those of Ervin and Mitchell and Dean are minor footnotes in scholarly treatises, the name and the discovery that will illuminate the 1973 will be Lubos Kohoutek.— William Safire, "Kohoutek's Comet", The New York Times (30 July 1973)[107]

Kohoutek was in its time the most publicized comet aside from Halley's Comet.[15] The media attention was brought about by a combination of factors, including the early predictions of its brightness, its passage concurrent with the Christmas and holiday season, the involvement of many observatories and powerful telescopes, and the possible effort of a manned spaceflight mission – Skylab 4 – to investigate the comet.[16][108] NASA also pursued an extensive public relations campaign that led to widespread coverage of the comet's approach in American newspapers in the final six months of 1973.[16] Dale D. Myers, the Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight at NASA, commented in July 1973 that "comets [of Kohoutek's] size come this close once in a century," further adding to the public interest.[16][13] On the 30 July 1973 edition of the New York Times, columnist William Safire wrote that Kohoutek "may well be the biggest, brightest, most spectacular astral display that living man has ever seen".[107] In August 1973, a reporter from The Mercury News in San Jose, California, wrote that researchers preparing to study the comet at NASA's Ames Research Center were calling Kohoutek "the comet of the century"; this honorific quickly became associated with the comet. NASA's decision to postpone the launch of Skylab 4 to support observations of the comet only further intensified public interest and added to the attention of the press towards Kohoutek after 16 August 1973. Despite more reserved and cautious statements from scientists regarding the comet's luminosity, stories referencing the more bullish and earlier estimates of Kohoutek's brightness continued to circulate as the comet drew closer, disregarding revised estimates.[16] One edition of Time placed the comet on its cover.[13] However, NASA spokespeople continued to relay an expectation that the comet would be a generational event. As November 1973 passed, newspapers began to more frequently convey the guarded skepticism that surrounded Kohoutek's brightness. Seizing the opportunity created by the comet in giving NASA good publicity, an adviser to NASA administrator James C. Fletcher proposed a half-hour television special featuring the comet, Skylab, and a Christmas message from the first family of the U.S. However, John Donnelly, the NASA Assistant Administrator for Public Affairs, derided the proposal because of its intertwining of politics with NASA. The proposal continued to be hotly contested within NASA but was eventually dropped. Although a spokesman for the Goddard Space Flight Center later stated that Kohoutek was a "roaring success" for science, "from a public relations point of view, it [was] a disaster."[16]

Cultural impact

It is among nonpatients that I have seen the most interest in the comet; in some instances the impact has already been profound. Many Christians have seen an umistakable link between the fact of Kohoutek's December 28 perihelion [...] and the Christmas observance. Some individuals have seemed to downplay the signifiance the event has for reasons of propriety or in the interest of appearing sensible. [...] A fair number of young adults have taken the comet to be some kind of sign, the significance to each individual varying with his specific religious or general spiritual outlook.

— Lawrence Weiner, letter to the editor,American Journal of Psychiatry (March 1974)[117]

With predictions of Kohoutek's exceptional brightness being well-circulated, the comet became a cultural and media phenomenon by mid-summer 1973, leading to widespread cometary paraphernalia, apparel, and accessories.[76] Sales of telescopes rose sharply leading up to the comet's anticipated appearance. Edmund Scientific Corporation reported a 200 percent increase in its sale of telescopes in 1973 relative to 1972.[3]: 2 Sales for telescopes and binoculars quadrupled at Macy's after the company ran a seven-column ad in the New York Times. Interest in popular astronomy books also increased as the comet neared. Pinnacle Books published and quickly sold 750,000 copies of astrologer Joseph Goodavage's book "The Comet Kohoutek", which described the comet as a "harbinger of God".[113][118] Astronomers appeared more frequently on television talk shows and were in greater demand as lecturers to speak on comets;[113] Carl Sagan appeared on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson to discuss the comet.[119]: 6

The timing of Kohoutek's visible apparition around

Because Kohoutek fell far short of expectations, its name became synonymous with spectacular disappointment.[123][124]: 199 Russell Baker described the comet as "the biggest flopperoo since 'Kelly' hit Broadway" and "the Edsel of the firmament", among other witty metaphors.[125] While newspapers had been touting the comet's brightness for the latter half of 1973, the anticlimactic display led to satirical and parodical reporting following Kohoutek's passage. For instance, the Chicago Tribune featured a satirical article linking the optimistic brightness predictions to an effort to distract the public from the Watergate scandal or to a conspiracy to boost telescope sales.[16] The widely circulated inaccurate projections came during a time of increasing distrust of the sciences that Time termed a "deepening disillusionment".[126] Mainstream media shied away from extensive coverage of comets following Kohoutek; despite Comet West becoming bright enough to be visible in daylight in March 1976, West received little attention from the press compared to the media frenzy that preceded Kohoutek.[76] Though astronomers and the sciences received backlash due to the comet's underwhelming performance, much of the general public's disdain was also directed towards astrologers and cultists who ascribed a transcendental significance to the comet's apparition.[118]

In response to the disappointing display from the comet, students at

In

See also

- Comet ISON – sungrazing comet that disintegrated upon passing close to the Sun

- C/1989 X1 (Austin) – fell short of brightness predictions in spring 1990

- Comet Ikeya–Seki – one of the brightest comets on record

- Oort cloud

- Interstellar object

Notes

- New York Times provided the phonetic pronunciation "ko-ho-tek" without any accented syllables.[2] A special report on the comet in Time gave the phonetic pronunciation "ko-hoe-tek".[3]: 1

- ^ Most comets have an albedo of around 0.04.

- ^ The designation C/1973 E1 reflects the modern comet designation scheme adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1995, and indicates that Comet Kohoutek appeared once and was the first comet discovered in the first half of March 1973. However, during the time of perihelion the comet was contemporaneously designated as 1973f as it was sixth comet discovered in 1973, or alternatively as 1973 XII as the comet was the twelfth to reach perihelion in 1973.[9][10][1]: 3

- ^ All mentions of apparent magnitude in this article refer to brightness in visible light unless otherwise noted.

- ^ a b Observations identified the cation of water (H

2O+

) in Kohoutek. It would not be until Comet Bradfield (1974 III) that neutral water (H

2O) was detected in a comet.[88] - main-belt asteroid about 10 km in diameter discovered by Kohoutek on 26 October 1971.[20]It is also known as 1980 RT3 and 1995 UZ44. It has been observed every year since 1998.

- ^ The first comet discovered by Kohoutek in 1973 was designated 1973e (modern designation: C/1973 D1) and has an orbital period of about 36,751 years. It reached its perihelion on 7 June 1973 and was last observed in October 1973.[21][15]

References

- ^ a b c d e Chapman, Robert D. (September 1973). Comet Kohoutek: A Teacher's Guide With Student Activities (PDF) (Technical Memorandum). Greenbelt, Maryland: NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ McElheny, Victor (7 January 1974). "Discoverer of Comet: Lubas Kohoutek". The New York Times. New York. p. 61. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "SPECIAL REPORT: Kohoutek: Comet of the Century". Time. Vol. 102, no. 25. 17 December 1973. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ Barycenter. Ephemeris Type: Elements and Center: @0 (To be outside planetary region, inbound epoch 1600 and outbound epoch 2500. Aphelia/orbital periods defined while in the planetary-region are misleading for knowing the long-term inbound/outbound solutions.)

- ^ a b c d "C/1973 E1 (Kohoutek)". Minor Planet Center. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d "C/1973 E1 (Kohoutek)". Small-Body Database Lookup. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 7 February 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ S2CID 120855634.

- ^ "Brightest comets seen since 1935". International Comet Quarterly. Archived from the original on 18 September 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "Comet Names and Designations; Comet Naming and Nomenclature; Names of Comets". International Comet Quarterly. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ S2CID 12022471.

- ^ Bibcode:2000JBAA..110....9H.

- ^ S2CID 120800003.

- ^ ISBN 9781316195727. Archivedfrom the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ S2CID 42320124.

- ^ Bibcode:1974QJRAS..15..433M.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Benson, Charles Dunlap; Compton, William David. "Appendix F: Comet Kohoutek". Living and Working in Space: A History of Skylab. Washington, D.C.: NASA. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- Bibcode:1976NASSP.393..380R. Archived(PDF) from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ a b c MSFC Skylab Kohoutek Project Report (PDF) (NASA Technical Memorandum). Huntsville, Alabama: NASA Marshall Space Flight Center. October 1974. NASA TM X-64880. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ S2CID 236815067.

- ^ "MPC object 8606". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ "C/1973 D1 (Kohoutek)". Small-Body Database Lookup. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 7 February 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ S2CID 121228906.

- ^ )

- ^ JSTOR 3958219.

- ^ S2CID 4255566.

- S2CID 86901151.

- ^ Horizons output. "Osculating Orbital Elements for Comet C/1973 E1 (Kohoutek)".

- ^ S2CID 116263177.

- ^ a b "Horizons Batch for Heliocentric distance for 2022-2030". JPL Horizons. Archived from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- S2CID 121046622.

- S2CID 119908758.

- ^ S2CID 120216058.

- )

- )

- S2CID 122229848.

- S2CID 121782993.

- ^ S2CID 123609347.

- S2CID 119698136.

- S2CID 120737009.

- S2CID 56252570.

- ^ S2CID 121989799.

- S2CID 121839693.

- S2CID 123614672.

- S2CID 118057535.

- S2CID 118694750.

- S2CID 4281170.

- ^ )

- S2CID 125675140.

- .

- ^ S2CID 4297924.

- ^ Herbig, George (1975). "Spectroscopy of the Coma and Tail". In Gary, Gilmer (ed.). Comet Kohoutek: A Workshop Held at Marshall Space Flight Center. Washington, D.C.: NASA. pp. 233–235.

- S2CID 43534328.

- ^ S2CID 45497893.

- ^ S2CID 120798083.

- ^ S2CID 120955159.

- Bibcode:1979NASCP2089..179M.

- S2CID 37048944.

- ^ S2CID 4287565.

- S2CID 123086883.

- ^ Bibcode:1977NASSP.370..923W. Archived(PDF) from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- S2CID 120962101.

- ^ S2CID 120188816.

- S2CID 120955304.

- ^ a b c d e Hale, Alan (27 December 2020). "Comet of the Week: Kohoutek 1973f". RocketSTEM. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- S2CID 42320124.

- ^ S2CID 54846398.

- S2CID 122741070.

- ^ S2CID 4163458.

- ^ Skylab 1/4 Technical Air-to-Ground Voice Transcription. Houston, Texas: NASA. November 1973.

- S2CID 119875072.

- Bibcode:1978QJRAS..19...38M.

- S2CID 119997643.

- Bibcode:1976AVest..10...70T.

- ^ S2CID 87707864.

- ^ ISBN 9781000523034.

- ^ a b c d Rao, Joe (22 January 2020). "How the 'comet of the century' became an astronomical disappointment". Space.com. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Huge comet at Christmas to be visible". The Montreal Star. No. 81. Montreal, Quebec. 5 April 1973. p. 13. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "New comet holds brilliant hope for star-gazers". The Morning News. Vol. 183, no. 83. United Press International. 6 April 1973. p. 10. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bibcode:1973JRASC..67L..25A.

- ^ "Kohoutek Predictions Toned Down". Sentinel Star. No. 315. Associated Press. 11 November 1973. p. 22C. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sullivan, Walter (17 January 1974). "Observations of Kohoutek Appear to Confirm Concept of Comets as 'snowballs'". The New York Times. New York. p. 24. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- S2CID 119799157.

- Bibcode:1977IrAJ...13...92O.

- hdl:2060/19760013988.

- ^ Whipple, Fred L. (1975). "Implications for Models and Origin of the Nucleus". In Gary, Gilmer (ed.). Comet Kohoutek: A Workshop Held at Marshall Space Flight Center. Washington, D.C.: NASA. pp. 227–232.

- ISBN 9789401088916.

- S2CID 4245004.

- ^ S2CID 40079180.

- ^ S2CID 121346176.

- ^ S2CID 31602518.

- )

- ^ Brandt, John C. (1 October 1981). The JOCR Program (PDF). JPL Mod. Observational Tech. for Comets (Report). NASA. pp. 171–184. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ "June". Astronautics and Aeronautics, 1973: Chronology of Science, Technology, and Policy. Washington, D.C.: NASA. 1975. p. 191. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ Sullivan, Walter (16 June 1973). "Plan to 'Intercept' Comet For Close Study Weighed". The New York Times. New York. p. 56. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ "Skylab 3 to study a brilliant comet". The New York Times. Associated Press. 17 August 1973. p. 18. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ Lundquist, Charles A. (ed.). "4. Observations of Comet Kohoutek". Skylab's Astronomy and Space Sciences. Washington, D.C.: NASA. Archived from the original on 13 November 2004. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ Mars, Kelli, ed. (5 February 2019). "45 Years Ago: Mariner 10 flies by Venus". NASA History. NASA. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ Dunne, James A.; Burgess, Eric (1978). "5. Venus Bound - Success and Near Failure". The Voyage of Mariner 10. Washington, D.C.: NASA. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ "Pioneer 06". Solar System Exploration. NASA. 11 August 2019. Archived from the original on 12 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- S2CID 34080360.

- ^ Sullivan, Walter (24 December 1973). "Revised Theory on Comets Offered". The New York Times. New York. p. 30. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "Reports in Brief". South African Journal of Science. 71. December 1975. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- Bibcode:1977NASSP4019.....B. NASA SP-4019.

- S2CID 119797846.

- S2CID 118607736.

- S2CID 120556703.

- ^ a b Safire, William (30 July 1973). "Kohoutek's Comet". The New York Times. New York. p. 27. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ISBN 9780060553432.

- ^ ISBN 9780393047721.

- ^ a b Segal, Jonathan (4 November 1973). "Science Cruises Becoming Popular". The New York Times. New York. p. 624. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ Barney, Lillian (2 December 1973). "'Comet of Century' to Get Dim Showing Over L.I." The New York Times. New York. p. 164. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ Schuman, Wendy (16 December 1973). "Star Fails to Show For QE2 Gazers". The New York Times. New York. p. 137. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Carlinsky, Dan (26 December 1973). "Business Boomlet Trailing Kohoutek". The New York Times. p. 65. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ISBN 9780553569971.

- ^ "Travel Notes: Survey Of Restrictions on Driving in Europe". The New York Times. New York. 9 December 1973. p. 594. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ "Colleges Aid Comet Watchers". The New York Times. New York. 16 December 1973. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- PMID 26951657.

- ^ JSTOR 20024229.

- ^ ISBN 9781107513501.

- ^ a b Fiske, Edward B. (24 December 1973). "Fundamentalists View 'Christmas Comet' as a Sign". The New York Times. New York. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ "Welcoming 'the age of Kohoutek'". San Francisco Examiner. Vol. 1974, no. 4. 27 January 1974. p. 3. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- S2CID 194041975.

- ^ MacPherson, Les (4 January 2013). "Comet's arrival may be a flop". Regina Leader-Post. Regina, Saskatchewan. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ISBN 9781441988102.

- ^ Baker, Russell (15 January 1974). "The Cosmic Flopperoo". The New York Times. New York. p. 37. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ISBN 9780813515380.

- ^ Greenberg, Annie. "Kohoutek Planning Commences" (PDF). The Other Side. Vol. 14, no. 2. Claremont, California. pp. 1–3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ Rojas, Luca (30 April 2010). "Kohoutek Music Festival Goes Big with GZA". The Student Life. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ Bainbridge, William Sins (2015). "The Impact of Space Exploration on Public Opinions, Attitudes, and Beliefs". In Dick, Steven J. (ed.). Historical Studies in the Societal Impact of Spaceflight (PDF). Washington, D.C.: NASA. p. 21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ISBN 9781780238586.

- ISBN 9780826423320.

- ISBN 9780190215781.

- ^ The Defenders #15 (September 1974), Marvel Comics

External links

- C/1973 E1 at the JPL Small-Body Database