Culture of ancient Rome

This article's lead section may be too long. (February 2023) |

The culture of ancient Rome existed throughout the almost 1,200-year history of the

.Life in ancient Rome revolved around the city of

The city of Rome was the largest

There was a very large amount of commerce between the provinces of the Roman Empire, since its roads and transportation technology were very efficient. The average costs of transport and the technology were comparable with 18th-century Europe. The later city of Rome did not fill the space within its ancient Aurelian Walls until after 1870.

The majority of the population under the jurisdiction of ancient Rome lived in the countryside in settlements with less than 10,000 inhabitants. Landlords generally resided in cities and their estates were left in the care of farm managers. The plight of rural slaves was generally worse than their counterparts working in urban aristocratic households. To stimulate a higher labor productivity most landlords freed a large number of slaves and many received wages, but in some rural areas poverty and overcrowding were extreme.[1] Rural poverty stimulated the migration of population to urban centers until the early 2nd century when the urban population stopped growing and started to decline.

Starting in the middle of the 2nd century BC, private

Against this human background, both the urban and rural setting, one of history's most influential civilizations took shape, leaving behind a cultural legacy that survives in part today.

The Roman Empire began when Augustus became the first emperor of Rome in 31 BC and ended in the west when the last Roman emperor,

Social structure

The center of the early social structure, dating from the time of the agricultural tribal city state, was the family, which was not only marked by biological relations but also by the legally constructed relation of patria potestas ("paternal power"). The pater familias was the absolute head of the family; he was the master over his wife (if she was given to him cum manu, otherwise the father of the wife retained patria potestas), his children, the wives of his sons (again if married cum manu which became rarer towards the end of the Republic), the nephews, the slaves and the freedmen (liberated slaves, the first generation still legally inferior to the freeborn), disposing of them and of their goods at will, even having them put to death.

Slavery and slaves were part of the social order. The slaves were mostly prisoners of war. There were slave markets where they could be bought and sold. Roman law was not consistent about the status of slaves, except that they were considered like any other moveable property. Many slaves were freed by the masters for fine services rendered; some slaves could save money to buy their freedom. Generally, mutilation and murder of slaves was prohibited by legislation,[citation needed] although outrageous cruelty continued. In AD 4, the Lex Aelia Sentia specified minimum age limits for both owners (20) and slaves (30) before formal manumission could occur.[2]

Apart from these families (called gentes) and the slaves (legally objects, mancipia, i.e., "kept in the [master's] hand") there were

The authority of the pater familias was unlimited, be it in civil rights as well as in criminal law. The king's duty was to be head over the military, to deal with foreign politics and also to decide on controversies between the gentes. The patricians were divided into three tribes (Ramnenses, Titientes, Luceres).

During the time of the

There were two assemblies: the

Over time, Roman law evolved considerably, as well as social views, emancipating (to increasing degrees) family members. Justice greatly increased, as well. The Romans became more efficient at considering laws and punishments.

Life in the ancient Roman cities revolved around the

Different types of outdoor and indoor entertainment, free of cost, were available in ancient Rome. Depending on the nature of the events, they were scheduled during daytime, afternoons, evenings, or late nights. Huge crowds gathered at the Colosseum to watch events such as events involving gladiators, combats between men, or fights between men and wild animals. The Circus Maximus was used for chariot racing.

Life in the countryside was slow-paced but lively, with numerous local festivals and social events. Farms were run by the farm managers, but estate owners would sometimes take a retreat to the countryside for rest, enjoying the splendor of nature and the sunshine, including activities like fishing, hunting, and riding. On the other hand, slave labor slogged on continuously, for long hours and all seven days, and ensuring comforts and creating wealth for their masters. The average farm owners were better off, spending evenings in economic and social interactions at the village markets. The day ended with a meal, generally left over from the noontime preparations.

Clothing

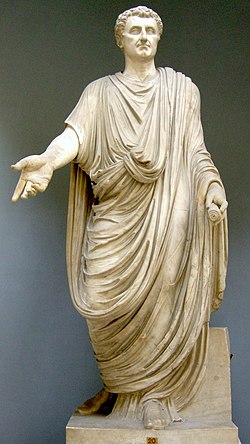

In ancient Rome, the cloth and the dress distinguished one class of people from the other class. The tunic worn by plebeians (common people) like shepherds was made from coarse and dark material, whereas the tunic worn by patricians was of linen or white wool. A magistrate would wear the tunica angusticlavi; senators wore tunics with purple stripes (clavi), called tunica laticlavi. Military tunics were shorter than the ones worn by civilians.

The many types of togas were also named. Boys, up until the festival of Liberalia, wore the toga praetexta, which was a toga with a crimson or purple border, also worn by magistrates in office. The toga virilis, (or toga pura) or man's toga was worn by men who had come of age to signify their citizenship in Rome. The toga picta was worn by triumphant generals and had embroidery of their skill on the battlefield. The toga pulla was worn in mourning.

Even

The bulla was a locket-like amulet worn by children. When about to marry, the woman would donate her lunula to the household gods, along with her toys, to signify maturity and womanhood.

Men typically wore a toga, and women wore a stola. The woman's stola was a dress worn over a tunic, and was usually brightly colored. A fibula (or brooch) would be used as ornamentation or to hold the stola in place. A palla, or shawl, was often worn with the stola.

Food

Since the beginning of the Republic until 200 BC, ancient Romans had very simple food habits. Simple food was generally consumed at around 11 o'clock, and consisted of bread, salad, olives, cheese, fruits, nuts, and cold meat left over from the dinner the night before. Breakfast was called ientaculum, lunch was prandium, and dinner was called cena. Appetizers were called gustatio, and dessert was called secunda mensa ("second table"). Usually, a nap or rest followed this.

The family ate together, sitting on stools around a table. Later on, a separate dining room with dining couches was designed, called a triclinium. Fingers were used to take foods which were prepared beforehand and brought to the diners. Spoons were used for soups.

Drinking non-watered wine on an empty stomach was regarded as boorish and a sure sign of alcoholism whose debilitating physical and psychological effects were already recognized in ancient Rome. An accurate accusation of being an alcoholic—in the gossip-crazy society of the city bound to come to light and easily verified—was a favorite and damaging way to discredit political rivals employed by some of Rome's greatest orators like Cicero and Julius Caesar. Prominent Roman alcoholics include Mark Antony, Cicero's own son Marcus (Cicero Minor) and the emperor Tiberius whose soldiers gave him the unflattering nickname Biberius Caldius Mero (lit. "Boozer of Pure Wine," Sueton Tib. 42,1). Cato the Younger was also known as a heavy drinker, frequently found stumbling home disoriented and the worse for wear in the early hours of morning by fellow citizens.

During the Imperial period, staple food of the lower class Romans (plebeians) was vegetable porridge and bread, and occasionally fish, meat, olives and fruits. Sometimes, subsidized or free foods were distributed in cities. The patrician's aristocracy had elaborate dinners, with parties and wines and a variety of comestibles. Sometimes, dancing girls would entertain the diners. Women and children ate separately, but in the later Empire period, with permissiveness creeping in, even decent women would attend such dinner parties.

Education

Schooling in a more formal sense was begun around 200 BC. Education began at the age of around six, and in the next six to seven years, boys and girls were expected to learn the basics of

Language

The native language of the Romans was Latin, an Italic language of the Indo-European family. Several forms of Latin existed, and the language evolved considerably over time, eventually becoming the Romance languages spoken today.

Initially a highly

Most of the surviving

The expansion of the Roman Empire spread Latin throughout Europe, and over time Vulgar Latin evolved and developed various

Although

Although Latin is an

The arts

Literature

Roman literature was from its very inception influenced heavily by Greek authors. Some of the earliest works currently discovered are of historical epics telling the early military history of Rome. As the Roman Republic expanded, authors began to produce poetry, comedy, history, and tragedy.

The Greeks and Romans had a tradition of historical scholarship that continues to influence writers to this day. Cato the Elder was a Roman senator, as well as the first man to write history in Latin. Although theoretically opposed to Greek influence, Cato the Elder wrote the first Greek inspired rhetorical textbook in Latin (91), and combined strains of Greek and Roman history into a method combining both.[4] One of Cato the Elder's great historical achievements was the Origines, which chronicles the story of Rome from Aeneas to his own day, but this document is now lost. In the second and early first centuries BC an attempt was made, led by Cato the Elder, to use the records and traditions that were preserved, in order to reconstruct the entire past of Rome. The historians engaged in this task are often referred to as the "Annalists", implying that their writings more or less followed chronological order.[4]

In 123 BC, an official endeavor was made to provide a record of the whole of Roman history. This work filled eighty books and was known as the , and its aftermath.

In the ancient world, poetry usually played a far more important part of daily life than it does today. In general, educated Greeks and Romans thought of poetry as playing a much more fundamental part of life than in modern times. Initially in Rome poetry was not considered a suitable occupation for important citizens, but the attitude changed in the second and first centuries BC.

Catullus and the associated group of Neoteric poets produced poetry following the Alexandrian model, which experimented with poetic forms challenging tradition. Catullus was also the first Roman poet to produce love poetry, seemingly autobiographical, which depicts an affair with a woman called Lesbia. Under the reign of the Emperor Augustus, Horace continued the tradition of shorter poems, with his Odes and Epodes. Martial, writing under the Emperor Domitian, was a famed author of epigrams, poems which were often abusive and censured public figures.

Roman prose developed its sonority, dignity, and rhythm in

Roman philosophical treatises have had great influence on the world, but the original thinking came from the Greeks. Roman philosophical writings are rooted in four 'schools' from the age of the Hellenistic Greeks.[9] The four 'schools' were that of the Epicureans, Stoics, Peripatetics, and the Academy.[9] Epicureans believed in the guidance of the senses, and identified the supreme goal of life to be happiness, or the absence of pain. Stoicism was founded by Zeno of Citium, who taught that virtue was the supreme good, creating a new sense of ethical urgency. The Peripatetics were followers of Aristotle, guided by his science and philosophy. The Academy was founded by Plato and was based on the Sceptic Pyro's idea that real knowledge could be acquired. The Academy also presented criticisms of the Epicurean and Stoic schools of philosophy.[10]

The genre of satire was traditionally regarded as a Roman innovation, and satires were written by, among others,

A great deal of the literary work produced by Roman authors in the early Republic was political or satirical in nature. The rhetorical works of Cicero, a self-distinguished linguist, translator, and philosopher, in particular, were popular. In addition, Cicero's personal letters are considered to be one of the best bodies of correspondence recorded in antiquity.

Visual art

Most early Roman painting styles show Etruscan influences, particularly in the practice of political painting. In the 3rd century BC, Greek art taken as booty from wars became popular, and many Roman homes were decorated with landscapes by Greek artists. Evidence from the remains at Pompeii shows diverse influence from cultures spanning the Roman world.

An early Roman style of note was "Incrustation", in which the interior walls of houses were painted to resemble colored marble. Another style consisted of painting interiors as open landscapes, with highly detailed scenes of plants, animals, and buildings.

Portrait sculpture during the period utilized youthful and classical proportions, evolving later into a mixture of realism and idealism. During the Antonine and Severan periods, more ornate hair and bearding became prevalent, created with deeper cutting and drilling. Advancements were also made in relief sculptures, usually depicting Roman victories.

Music

Music was a major part of everyday life in ancient Rome. Many private and public events were accompanied by music, ranging from nightly dining to military parades and manoeuvres.

Some of the instruments used in Roman music are the tuba, cornu, aulos, askaules, flute, panpipes, lyre, lute, cithara, tympanum, drums, hydraulis and the sistrum.

Architecture

In its initial stages, the ancient Roman architecture reflected elements of architectural styles of the Etruscans and the Greeks. Over a period of time, the style was modified in tune with their urban requirements, and civil engineering and building construction technology became developed and refined. The Roman concrete has remained a riddle,[11] and even after more than two thousand years some ancient Roman structures still stand magnificently, like the Pantheon (with one of the largest single span domes in the world) located in the business district of today's Rome.

The architectural style of the capital city of ancient Rome was emulated by other urban centers under Roman control and influence,

Sports and entertainment

The ancient city of Rome had a place called the Campus, a sort of drill ground for Roman soldiers, which was located near the Tiber. Later, the Campus became Rome's track and field playground, which even Julius Caesar and Augustus were said to have frequented. Imitating the Campus in Rome, similar grounds were developed in several other urban centers and military settlements.

In the Campus, the youth assembled to play, exercise, and indulge in appropriate sports, which included

There were several other activities to keep people engaged like

, 60,000 persons could be accommodated. There are also accounts of the Colosseum's floor being flooded to hold mock naval battles for the public to watch.In addition to these, Romans also spent their share of time in bars and brothels, and graffiti[14] carved into the walls of these buildings was common. Based on the number of messages found on bars, brothels, and bathhouses, it's clear that they were popular places of leisure and people spent a deal of time there. The walls of the rooms in the lupanar, one of the only known remaining brothels in Pompeii, are covered in graffiti in a multitude of languages, showcasing how multicultural ancient Rome was.

Religion

| Religion in ancient Rome |

|---|

|

| Practices and beliefs |

| Priesthoods |

| Deities |

| Related topics |

|

The Romans thought of themselves as highly religious,

The priesthoods of public religion were held by members of the

Roman religion was thus mightily pragmatic and contractual, based on the principle of

For ordinary Romans, religion was a part of daily life.

The Romans are known for the great number of deities they honored. The presence of Greeks on the Italian peninsula from the beginning of the historical period influenced Roman culture, introducing some religious practices that became as fundamental as the cult of Apollo. The Romans looked for common ground between their major gods and those of the Greeks, adapting Greek myths and iconography for Latin literature and Roman art. Etruscan religion was also a major influence, particularly on the practice of augury, since Rome had once been ruled by Etruscan kings.

As the Romans extended their dominance throughout the Mediterranean world, their policy in general was to

One way that Rome incorporated diverse peoples was by supporting their religious heritage, building temples to local deities that framed their theology within the hierarchy of Roman religion. Inscriptions throughout the Empire record the side-by-side worship of local and Roman deities, including dedications made by Romans to local gods.

In the wake of the

From the 2nd century onward, the

Constantine ruled the Roman Empire as sole emperor for the remainder of his reign. Some scholars allege that his main objective was to gain unanimous approval and submission to his authority from all classes, and therefore chose Christianity to conduct his political

However, if Constantine himself sincerely converted to Christian religion or remained loyal to Paganism is still a matter of debate between scholars (see also Constantine's Religious policy).[28] His formal conversion to Christianity in 312 is almost universally acknowledged among historians,[27][29] despite that he was baptized only on his deathbed by the Arian bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia (337);[30] the real reasons behind it remain unknown and are debated too.[28][29] According to Hans Pohlsander, Professor Emeritus of History at the University at Albany, SUNY, Constantine's conversion was just another instrument of Realpolitik

The prevailing spirit of Constantine's government was one of conservatorism. His conversion to and support of Christianity produced fewer innovations than one might have expected; indeed they served an entirely conservative end, the preservation and continuation of the Empire.

— Hans Pohlsander, The Emperor Constantine[31]

The Emperor and

Philosophy

Ancient Roman philosophy was heavily influenced by

During this time Athens declined as an intellectual center of thought while new sites such as Alexandria and Rome hosted a variety of philosophical discussion.[34]

Science

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2020) |

See also

- Classical antiquity

- Gallo-Roman culture

- Roman Britain

- Romanization

- Romanization of Hispania

- Theatre of ancient Rome

- Romanization of Anatolia

References

- ^ For example, a Romano-Egyptian text attests to the sharing of one small farmhouse by 42 people; elsewhere, six families held common interest in a single olive tree. See Alfoldy, Geza., The Social History of Rome (Routledge Revivals) 2014 (online e-edition, unpaginated: accessed October 11th, 2016)

- ^ Gardner, Jane (1991). "The Purpose of the Lex Fufia Caninia". Echos du Monde Classique: Classical Views. 35, 1: 21–39 – via Project MUSE.

- ^ E. M. Jellinek, Drinkers and Alcoholics in Ancient Rome.

- ^ a b c Grant, Michael (1954). Roman Literature. Cambridge England: University Press. pp. 91–94.

- ^ a b Grant, Michael (1954). Roman Literature. Cambridge England: University Press. p. 134.

- ^ Tenney, Frank (1930). Life and Literature in the Roman Republic. Berkeley California: University of California Press. p. 132.

- ^ Tenney, Frank (1930). Life and Literature in the Roman Republic. Berkeley California: University of California Press. p. 35.

- ^ a b Grant, Michael (1954). Roman Literature. Cambridge England: University Press. pp. 78–84.

- ^ a b Grant, Michael (1954). Roman Literature. Cambridge England: University Press. pp. 30–45.

- ^ Grant, Michael (1954). Roman Literature. Cambridge England: University Press. pp. Notes.

- ^ The Riddle of Ancient Roman Concrete, By David Moore, P.E., 1995, Retired Professional Engineer, Bureau of Reclamation (This article first appeared in "The Spillway" a newsletter of the US Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation, Upper Colorado Region, February, 1993)

- ^ "Roman Art and Architecture". UCCS.edu. Archived from the original on September 8, 2006. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ Lepcis Magna - Window on the Roman World in North Africa

- ^ Harvey, Brian. "Graffiti from Pompeii". Graffiti from Pompeii. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-4691-0298-6.

- ^ Jörg Rüpke, "Roman Religion – Religions of Rome," in A Companion to Roman Religion (Blackwell, 2007), p. 4.

- ^ Matthew Bunson, A Dictionary of the Roman Empire (Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 246.

- ^ "This mentality," notes John T. Koch, "lay at the core of the genius of cultural assimilation which made the Roman Empire possible"; entry on "Interpretatio romana," in Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia (ABC-Clio, 2006), p. 974.

- ^ Rüpke, "Roman Religion – Religions of Rome," p. 4; Benjamin H. Isaac, The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity (Princeton University Press, 2004, 2006), p. 449; W.H.C. Frend, Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church: A Study of Conflict from the Maccabees to Donatus (Doubleday, 1967), p. 106.

- ISBN 0-8028-3784-0.

- ^ Janet Huskinson, Experiencing Rome: Culture, Identity and Power in the Roman Empire (Routledge, 2000), p. 261.

- ^ A classic essay on this topic is Arnaldo Momigliano, "The Disadvantages of Monotheism for a Universal State," in Classical Philology, 81.4 (1986), pp. 285–297.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8028-4913-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-03-00-09839-6.

- Tacitus on Christ.

- Latin Christian polemic and apologetics.

- ^ a b Wendy Doniger (ed.), "Constantine I," in Britannica Encyclopedia of World Religions (Encyclopædia Britannica, 2006), p. 262.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-81838-4.

- ^ ISBN 0-8020-6369-1.

- ISBN 0-415-31938-2; Lenski, "Reign of Constantine" (The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine), p. 82.

- ^ Pohlsander, The Emperor Constantine, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Stefan Heid, "The Romanness of Roman Christianity," in A Companion to Roman Religion (Blackwell, 2007), pp. 406–426; on vocabulary in particular, Robert Schilling, "The Decline and Survival of Roman Religion," in Roman and European Mythologies (University of Chicago Press, 1992, from the French edition of 1981), p. 110.

- ^ "Roman Philosophy | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy".

- OCLC 870243656.

Bibliography

- Elizabeth S. Cohen, Honor and Gender in the Streets of Early Modern Rome, The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Spring, 1992), pp. 597-625

- The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

- Tom Holland, The Last Years of the Roman Republic ISBN 0-385-50313-X

- Ramsay MacMullen, 2000. Romanization in the Time of Augustus (Yale University Press)

- Paul Veyne, editor, 1992. A History of Private Life: I From Pagan Rome to Byzantium (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press)

- Karl Wilhelm Weeber, 2008. Nachtleben im Alten Rom (Primusverlag)

- Karl Wilhelm Weeber, 2005. Die Weinkultur der Römer

- J.H. D'Arms, 1995. Heavy drinking and drunkenness in the Roman world, in O.Murray In Vino Veritas

External links

- An interactive Roman map Archived 2009-09-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Rome Reborn − A Video Tour through Ancient Rome based on a digital model Archived 2011-08-10 at the Wayback Machine