Roman mythology

| Mythology |

|---|

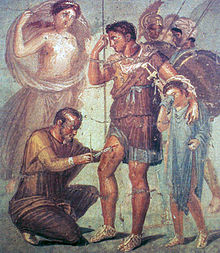

Roman mythology is the body of

The Romans usually treated their traditional narratives as historical, even when these have miraculous or supernatural elements. The stories are often concerned with politics and morality, and how an individual's personal integrity relates to his or her responsibility to the community or Roman state. Heroism is an important theme. When the stories illuminate Roman religious practices, they are more concerned with ritual, augury, and institutions than with theology or cosmogony.[1]

Roman mythology also draws on

Latin literature was widely known in Europe throughout the

Nature of Roman myth

Because ritual played the central role in Roman religion that myth did for the Greeks, it is sometimes doubted that the Romans had much of a native mythology. This perception is a product of Romanticism and the classical scholarship of the 19th century, which valued Greek civilization as more "authentically creative."[3] From the Renaissance to the 18th century, however, Roman myths were an inspiration particularly for European painting.[4] The Roman tradition is rich in historical myths, or legends, concerning the foundation and rise of the city. These narratives focus on human actors, with only occasional intervention from deities but a pervasive sense of divinely ordered destiny. In Rome's earliest period, history and myth have a mutual and complementary relationship.[5] As T. P. Wiseman notes:

The Roman stories still matter, as they mattered to

tyranny?[4]

Major sources for Roman myth include the .

Founding myths

The Aeneid and Livy's early history are the best extant sources for

Other myths

The characteristic myths of Rome are often political or moral, that is, they deal with the development of Roman government in accordance with divine law, as expressed by Roman religion, and with demonstrations of the individual's adherence to moral expectations (mos maiorum) or failures to do so.

- Rape of the Sabine women, explaining the importance of the Sabinesin the formation of Roman culture, and the growth of Rome through conflict and alliance.

- Numa Pompilius, the Sabine second king of Rome who consorted with the nymph Egeria and established many of Rome's legal and religious institutions.

- Servius Tullius, the sixth king of Rome, whose mysterious origins were freely mythologized and who was said to have been the lover of the goddess Fortuna.

- The Tarpeian Rock, and why it was used for the execution of traitors.

- early Roman monarchyand led to the establishment of the Republic.

- Cloelia, a Roman woman taken hostage by Lars Porsena. She escaped the Clusian camp with a group of Roman virgins.

- Horatius at the bridge, on the importance of individual valor.

- Mucius Scaevola, who thrust his right hand into the fire to prove his loyalty to Rome.

- Praeneste.[7]

- Manlius and the geese, about divine intervention at the Gallic siege of Rome.[8]

- Stories pertaining to the Nonae Caprotinae and Poplifugia festivals.[9]

- Coriolanus, a story of politics and morality.

- The Etruscan city of Corythus as the "cradle" of Trojan and Italian civilization.[10]

- The arrival of the Great Mother (Cybele) in Rome.[11]

Religion and myth

Narratives of divine activity played a more important role in the system of Greek religious belief than among the Romans, for whom ritual and cult were primary. Although Roman religion did not have a basis in

The earliest pantheon included Janus,

The gods represented distinctly the practical needs of daily life, and Ancient Romans scrupulously accorded them the appropriate rites and offerings. Early Roman divinities included a host of "specialist gods" whose names were invoked in the carrying out of various specific activities. Fragments of old ritual accompanying such acts as plowing or sowing reveal that at every stage of the operation a separate deity was invoked, the name of each deity being regularly derived from the verb for the operation. Tutelary deities were particularly important in ancient Rome.

Thus,

The 19th-century scholar

Foreign gods

The absorption of neighboring local gods took place as the Roman state conquered neighboring territories. The Romans commonly granted the local gods of a conquered territory the same honors as the earlier gods of the

In some instances, deities of an enemy power were formally invited through the ritual of evocatio to take up their abode in new sanctuaries at Rome.

Communities of foreigners (

Astronomy

Many astronomical objects are named after Roman deities, like the planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and Neptune.

In Roman and Greek mythology, Jupiter places his son born by a mortal woman, the infant

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2022) |

See also

- List of Ovid's Metamorphoses characters

- List of Roman deities

- Roman Polytheistic Reconstructionism

References

- ^ John North, Roman Religion (Cambridge University Press, 2000) pp. 4ff.

- ^ Rengel, Marian; Daly, Kathleen N. (2009). Greek and Roman Mythology, A to Z. United States: Facts On File, Incorporated. p. 66.

- ^ T. P. Wiseman, The Myths of Rome (University of Exeter Press, 2004), preface (n.p.).

- ^ a b Wiseman, The Myths of Rome, preface.

- ^ Alexandre Grandazzi, The Foundation of Rome: Myth and History (Cornell University Press, 1997), pp. 45–46.

- ^ See also Lusus Troiae.

- ^ J.N. Bremmer and N.M. Horsfall, Roman Myth and Mythography (University of London Institute of Classical Studies, 1987), pp. 49–62.

- ^ Bremmer and Horsfall, pp. 63–75.

- ^ Bremmer and Horsfall, pp. 76–88.

- ^ Bremmer and Horsfall, pp. 89–104; Larissa Bonfante, Etruscan Life and Afterlife: A Handbook of Etruscan Studies (Wayne State University Press, 1986), p. 25.

- ^ Bremmer and Horsfall, pp. 105–111.

- ISBN 978-0-231-51487-3.

- ISBN 978-0-521-20069-1.

- ^ Cicero, De domo sua 138.

- ^ Jerzy Linderski, "The libri reconditi", Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 89 (1985) 207–234.

- ^ Georg Wissowa, De dis Romanorum indigetibus et novensidibus disputatio (1892), full text (in Latin) online.

- ^ Arnaldo Momigliano, "From Bachofen to Cumont", in A.D. Momigliano: Studies on Modern Scholarship (University of California Press, 1994), p. 319; Franz Altheim, A History of Roman Religion, as translated by Harold Mattingly (London, 1938), pp. 110–112; Mary Beard, J.A. North and S.R.F. Price. Religions of Rome: A History (Cambridge University Press, 1998), vol. 1, p. 158, note 7.

- ^ William Warde Fowler, The Religious Experience of the Roman People (London, 1922) pp. 157 and 319; J.S. Wacher, The Roman World (Routledge, 1987, 2002), p. 751.

- ^ "Myths about the Milky Way". judy-volker.com. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-19-511957-2.

- ISBN 978-0-19-538839-8.

Sources

- Beard, Mary. 1993. "Looking (Harder) for Roman Myth: Dumézil, Declamation, and the Problems of Definition." In Mythos in Mythenloser Gesellschaft: Das Paradigma Roms. Edited by Fritz Graf, 44–64. Stuttgart, Germany: Teubner.

- Braund, David, and Christopher Gill, eds. 2003. Myth, History, and Culture in Republican Rome: Studies in Honour of T. P. Wiseman. Exeter, UK: Univ. of Exeter Press.

- Cameron, Alan. 2004. Greek Mythography in the Roman World. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Dumézil, Georges. 1996. Archaic Roman Religion. Rev. ed. Translated by Philip Krapp. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press.

- Fox, Matthew. 2011. "The Myth of Rome" In A Companion to Greek Mythology. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. Literature and Culture.Edited by Ken Dowden and Niall Livingstone. Chichester; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Gardner, Jane F. 1993. Roman Myths: The Legendary Past. Austin: Univ. of Texas Press.

- Grandazzi, Alexandre. 1997. The Foundation of Rome: Myth and History. Translated by Jane Marie Todd. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press.

- Hall, Edith 2013. "Pantomime: Visualising Myth in the Roman Empire." In Performance in Greek and Roman Theatre. Edited by George Harrison and George William Mallory, 451–743. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

- Miller, Paul Allen. 2013. "Mythology and the Abject in Imperial Satire." In Classical Myth and Psychoanalysis: Ancient and Modern Stories of the Self. Edited by Vanda Zajko and Ellen O'Gorman, 213–230. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

- Newby, Zahra. 2012. "The Aesthetics of Violence: Myth and Danger in Roman Domestic Landscapes." Classical Antiquity 31.2: 349–389.

- Wiseman, T. P. 2004. The Myths of Rome. Exeter: Univ. of Exeter Press.

- Woodard, Roger D. 2013. Myth, Ritual, and the Warrior in Roman and Indo-European Antiquity. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC) (1981–1999, Artemis-Verlag, 9 volumes), Supplementum (2009, Artemis_Verlag).

- LIMC-France (LIMC): Databases Dedicated to Graeco-Roman Mythology and its Iconography.