Makuria

Kingdom of Makuria Arabic )al-Muqurra | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5th century–1518 Late 15th/16th century | |||||||||||

|

The flag of Makuria according to the disputed – discuss] | |||||||||||

The Kingdom of Makuria at its maximum territorial extent around 960, after a raid that reached as far north as Akhmim | |||||||||||

| Capital | Dongola (until 1365) Gebel Adda (from 1365) | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Nubian Coptic Greek Arabic[2] | ||||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• fl. 651–652 | Qalidurut (first known king) | ||||||||||

• fl. 1463–1484 | Joel (last known king) | ||||||||||

• c. 1520–1526 | Queen Gaua (new last known ruler) | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 5th century | ||||||||||

• Royal court fled to Gebel Adda, Dongola abandoned | 1365 | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1518 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Gold

Solidus Dircham | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Sudan Egypt | ||||||||||

Makuria (

Coming into being after the collapse of the

In 651 an

Increased aggression from

Sources

Makuria is much better known than its neighbor

The Nubians were a literate society, and a fair body of writing survives from the period. These documents were written in the

The construction of the

History

Early period (5th–8th century)

By the early 4th century, if not before, the

Already at the time of the foundation of Dongola contacts were maintained with the

In the 7th century, Makuria annexed its northern neighbour Nobatia. While there are several contradicting theories,

Between 639 and 641 the Muslim Arabs

The 8th century was a period of consolidation. Under king

Zenith (9th–11th century)

The kingdom was at its peak between the 9th and 11th centuries.[62] During the reign of king Ioannes in the early 9th century, relations with Egypt were cut and the Baqt ceased to be paid. Upon Ioannes' death in 835 an Abbasid emissary arrived, demanding the Makurian payment of the missing 14 annual payments and threatening with war if the demands are not met.[63] Thus confronted with a demand for more than 5000 slaves,[50] Zakharias III "Augustus", the new king, had his son Georgios I crowned king, probably to increase his prestige, and sent him to the caliph in Baghdad to negotiate.[d] His travel drew much attention at the time.[65] The 12th-century Syriac Patriarch Michael described Georgios and his retinue in some detail, writing that Georgios rode a camel, wielded a sceptre and a golden cross in his hands and that a red umbrella was carried over his head. He was accompanied by a bishop, horsemen and slaves, and to his left and right were young men wielding crosses.[66] A few months after Georgios arrived in Baghdad he, described as educated and well-mannered, managed to convince the caliph of remitting the Nubian debts and reducing the Baqt payments to a three-year rhythm.[67] In 836[68] or early 837[69] Georgios returned to Nubia. After his return a new church was built in Dongola, the Cruciform Church, which had an approximate height of 28 metres (92 ft) and came to be the largest building in the entire kingdom.[70] A new palace, the so-called Throne Hall of Dongola, was also built,[71] showing strong Byzantine influences.[72]

In 831 a punitive campaign of the Abbasid caliph al-Mu'tasim defeated the Beja east of Nubia. As a result, they had to submit to the Caliph, thus expanding nominal Muslim authority over much of the Sudanese Eastern Desert.[73] In 834 al-Mu'tasim ordered that the Egyptian Arab Bedouins, who had been declining as a military force since the rise of the Abbasids, were not to receive any more payments. Discontented and dispossessed, they pushed southwards. The road into Nubia was, however, blocked by Makuria: while there existed communities of Arab settlers in Lower Nubia the great mass of the Arab nomads was forced to settle among the Beja,[74] driven also by the motivation to exploit the local gold mines.[75] In the mid-9th century the Arab adventurer al-Umari hired a private army and settled at a mine near Abu Hamad in eastern Makuria. After a confrontation between both parties, al-Umari occupied Makurian territories along the Nile.[76] King Georgios I sent an elite force[77] commanded by his son in law, Nyuti,[78] but he failed to defeat the Arabs and rebelled against the crown himself. King Georgios then sent his oldest son, presumably the later Georgios II, but he was abandoned by his army and was forced to flee to Alodia. The Makurian king then sent another son, Zacharias, who worked together with al-Umari to kill Nyuti before eventually defeating al-Umari himself and pushing him into the desert.[77] Afterward, al-Umari attempted to establish himself in Lower Nubia, but was soon pushed out again before finally being murdered during the reign of the Tulunid Sultan Ahmad ibn Tulun (868–884).[79]

During the rule of the autonomous

The kingdom of Makuria was, at least temporarily, exercising influence over the Nubian-speaking populations of

During the second half of the 11th century, Makuria saw great cultural and religious reforms, referred to as "Nubization". The main initiator has been suggested to have been Georgios, the archbishop of Dongola and hence the head of the Makurian church.[101] He seems to have popularized the Nubian language as written language to counter the growing influence of Arabic in the Coptic Church[102] and introduced the cult of dead rulers and bishops as well as indigenous Nubian saints. A new, unique church was built in Banganarti, probably becoming one of the most important ones in the entire kingdom.[103] In the same period Makuria also began to adopt a new royal dress[104] and regalia and perhaps also Nubian terminology in administration and titles, all suggested to have initially come from Alodia in the south.[102][105]

Decline (12th century – 1365)

In 1171

There are no records from travelers to Makuria from 1172 to 1268,[115] and the events of this period have long been a mystery, although modern discoveries have shed some light on this era. During this period Makuria seems to have entered a steep decline. The best source on this is Ibn Khaldun, writing in the 14th century, who blamed it on Bedouin invasions similar to what the Mamluks were dealing with. Other factors for the decline of Nubia might have been the change of African trade routes[116] and a severe dry period between 1150 and 1500.[117]

Matters would change with the rise of the

Thanks to the

Internal difficulties seem to have also hurt the kingdom. King David's cousin Shekanda claimed the throne and traveled to Cairo to seek the support of the Mamluks. They agreed and took over Nubia in 1276, and placed Shekanda on the throne. The Christian Shekanda then signed an agreement making Makuria a vassal of Egypt, and a Mamluk garrison was stationed in Dongola. A few years later, Shamamun, another member of the Makurian royal family, led a rebellion against Shekanda to restore Makurian independence. He eventually defeated the Mamluk garrison and took the throne in 1286 after separating from Egypt and betraying the peace deal. He offered the Egyptians an increase in the annual Baqt payments in return for scrapping the obligations to which Shekanda had agreed. The Mamluk armies were occupied elsewhere, and the Sultan of Egypt agreed to this new arrangement.[citation needed]

After a period of peace, King Karanbas defaulted on these payments, and the Mamluks again occupied the kingdom in 1312. This time, a Muslim member of the Makurian dynasty was placed on the throne. Sayf al-Din Abdullah Barshambu began converting the nation to Islam and in 1317 the throne hall of Dongola was turned into a mosque. This was not accepted by other Makurian leaders and the nation fell into civil war and anarchy later that year. Barshambu was eventually killed and succeeded by Kanz ad-Dawla. While ruling, his tribe, the Banu Khanz, acted a puppet dynasty of the Mamluks.[145] King Karanbas tried to wrestle control from Kanz ad-Dwala in 1323 and eventually seized Dongola, but was ousted just one year later. He retreated to Aswan for another chance to seize the throne, but it never came.[146]

The ascension of the Muslim king Abdallah Barshambu and his transformation of the throne hall into a mosque has often been interpreted as the end of Christian Makuria. This conclusion is erroneous, since Christianity evidently remained vital in Nubia.

It was also in the mid 14th century, more particularly after 1347, when Nubia would have been devastated by the plague. Archaeology confirms a rapid decline of the Christian Nubian civilization since then. Due to their small population the plague might have cleansed entire landscapes from its Nubian inhabitants.[154]

In 1365, there occurred yet another short, but disastrous civil war. The current king was killed in battle by his rebelling nephew, who had allied himself with the Banu Ja'd tribe. The brother of the deceased king and his retinue fled to a town called Daw in the Arabic sources, most likely identical with Gebel Adda in Lower Nubia.[155] The usurper then killed the nobility of the Banu Ja'd, probably because he could not trust them anymore, and destroyed and pillaged Dongola, then traveled to Gebel Adda to ask his uncle for forgiveness. Thus Dongola was left to the Banu Ja'd and Gebel Adda became the new capital.[156]

Terminal period (1365–late 15th century)

The Makurian rump state

Both the usurper and the rightful heir, and most likely even the king that was killed during the usurpation, were Christian.[157] Now residing in Gebel Adda, the Makurian kings continued their Christian traditions.[158] They ruled over a reduced rump state with a confirmed north–south extension of around 100 km, albeit it might have been larger in reality.[159] Located in a strategically irrelevant periphery, the Mamluks left the kingdom alone.[158] In the sources this kingdom appears as Dotawo. Until recently it was commonly assumed that Dotawo was, before the Makurian court shifted its seat to Gebel Adda, just a vasal kingdom of Makuria, but it is now accepted that it was merely the Old Nubian self-designation for Makuria.[160]

The last known king is Joel, who is mentioned in a 1463 document and in an inscription from 1484. Perhaps it was under Joel when the kingdom witnessed a last, brief renaissance.[161] After the death or deposition of king Joel the kingdom might have collapsed.[162] The cathedral of Faras came out of use after the 15th century, just as Qasr Ibrim was abandoned by the late 15th century.[127] The palace of Gebel Adda came out of use after the 15th century as well.[159] In 1518, there is one last mention of a Nubian ruler, albeit it is unknown where he resided and if he was Christian or Muslim.[163] However, in 2023 Adam Simmons pointed to the existence in the 1520s of Christian Nubian Queen Gaua.[164] There were no traces of an independent Christian kingdom when the Ottomans occupied Lower Nubia in the 1560s,[162] while the Funj had come into possession of Upper Nubia south of the third cataract.

Further developments

Political

By the early 15th century, there is mention of a king of Dongola, most likely independent from the influence of the Egyptian sultans.

It is possible that some petty kingdoms that continued the Christian Nubian culture developed in the former Makurian territory, for example on Mograt island, north of

In 1412, the

Ethnographic and linguistic

The Nubians

Today, the Nubian language is in the process of being replaced by Arabic.[176] Furthermore, the Nubians have increasingly started to claim to be Arabs descending from Abbas, disregarding their Christian Nubian past.[177]

Culture

Christian Nubia was historically considered to be something of a backwater, because their graves were small and lacking the grave goods of previous eras.[178] Modern scholars understand that this was due to cultural differences, and that the Makurians actually had rich and vibrant arts and culture.

Languages

Four languages were used in Makuria:

Arts

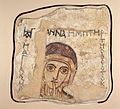

Wallpaintings

As of 2019, around 650 murals distributed over 25 sites have been recorded,

- Gallery

-

Christ, Abu Oda (second half of the 7th century)

-

Wadi es-Sebua(late 7th-early 8th century)

-

St. Anne, Faras (8th-first half of the 9th century)

-

Apostle Saints Peter and John (8th-first half of the 10th century)

-

Warrior saint with spear and shield, Faras (9th century)

-

Archangel Gabrielwith sword, Faras (9th-first quarter of the 10th century)

-

St. Gabriel with a trumpet and orb. (9th century)

-

Madonna and Christ Child, Faras (10th century)

-

Three youths in the furnace, Faras (last quarter of the 10th century)

-

Theophany and bishop, Abdallah Nirqi (late 10th-early 11th century)

-

Magi on horseback, Faras (late 10th–early 11th century

-

Bishop Marianos withMadonna and Christ Child, Faras (first half of the 11th century)

-

Elaborate cross, Faras (11th century)

-

Nubian dignitary and Christ, Faras (12th century)

-

Baptism of Christ, Old Dongola (12th–13th century)

-

Warrior saint, Meinarti (late 13th-mid 14th century)

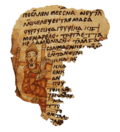

Manuscript illustrations

-

Old Nubian manuscript from Serra East (973) showing some richly robed individual

-

Detail of a manuscript from Serra East showing a sitting man

-

Old Nubian manuscript from Qasr Ibrim showing a bishop

-

St. Menas and boatman on an Old Nubian manuscript found in Edfu

Pottery

Role of women

The Christian Nubian society was

Women had access to education[197] and there is evidence that, like in Byzantine Egypt, female scribes existed.[199] Private land tenure was open to both men and women, meaning that both could own, buy and sell land. Transfers of land from mother to daughter were common.[200] They could also be the patrons of churches and wall paintings.[201] Inscriptions from the cathedral of Faras indicate that around every second wall painting had a female sponsor.[202] An inscription from Faras suggests that women could also serve as deacons.[203]

Hygiene

Latrines were a common sight in Nubian domestic buildings.[204] In Dongola all houses had ceramic toilets.[205] Some houses in Cerra Matto (Serra East) featured privies with ceramic toilets, which were connected to a small chamber with a stone-lined clean out window to the outside and a brick ventilation flue.[206] Biconical pieces of clay served as the equivalent of toilet paper.[207]

One house in Dongola featured a vaulted bathroom, fed by a system of pipes attached to a water tank.[208] A furnace heated up both the water and the air, which was circulated into the richly decorated bathroom via flues in the walls.[68] The monastic complex of Hambukol is thought to have had a room serving as a steam bath.[208] The Ghazali monastery in Wadi Abu Dom also might have featured several bathrooms.[209]

Government

Makuria was a monarchy ruled by a king based in Dongola. The king was also considered a priest and could perform mass. How succession was decided is not clear. Early writers indicate it was from father to son. After the 11th century, however, it seems clear that Makuria was using the uncle-to-sister's-son system favoured for millennia in Kush. Shinnie speculates that the later form may have actually been used throughout, and that the early Arab writers merely misunderstood the situation and incorrectly described Makurian succession as similar to what they were used to.[210] A Coptic source from the mid 8th century refers to king Cyriacos as "orthodox Abyssinian king of Makuria" as well as "Greek king", with "Abyssinian" probably reflecting the Miaphysite Coptic church and "Greek" the Byzantine Orthodox one.[211] In 1186 king Moses Georgios called himself "king of Alodia, Makuria, Nobadia, Dalmatia[g] and Axioma."[213]

Little is known about government below the king. A wide array of officials, generally using Byzantine titles, are mentioned, but their roles are never explained. One figure who is well-known, thanks to the documents found at

The

Kings

Religion

Paganism

One of the most debated issues among scholars is over the religion of Makuria. Up to the 5th century the old faith of

Christianity

Archaeological evidence in this period finds a number of Christian ornaments in Nubia, and some scholars feel that this implies that conversion from below was already taking place. Others argue that it is more likely that these reflected the faith of the manufacturers in Egypt rather than the buyers in Nubia.

Certain conversion came with a series of 6th-century missions. The

After this point the exact course of Makurian Christianity is much disputed. It is clear that by c. 710 Makuria had become officially

Church infrastructure

The Makurian church was divided into seven bishoprics:

Monasticism

Unlike in Egypt, there is not much evidence for monasticism in Makuria. According to Adams there are only three archaeological sites that are certainly monastic. All three are fairly small and quite Coptic, leading to the possibility that they were set up by Egyptian refugees rather than indigenous Makurians.[225] Since the 10th/11th century the Nubians had their own monastery in the Egyptian Wadi El Natrun valley.[226]

Islam

The Baqt guaranteed the security of Muslims travelling in Makuria,[227] but prohibited their settlement in the kingdom. However, the latter point was, not maintained:[228] Muslim migrants, probably merchants and artisans,[229] are confirmed to have settled in Lower Nubia from the 9th century and to have intermarried with the locals, thus laying the foundation for a small Muslim population[230] as far south as the Batn el-Hajar.[231] Arabic documents from Qasr Ibrim confirm that these Muslims had their own communal judiciary,[232] but still regarded the Eparch of Nobatia as their suzerain.[233] It seems likely that they had own mosques, though none have been identified archaeologically,[229] with a possible exception being in Gebel Adda.[228]

In Dongola, there was no larger number of Muslims until the end of the 13th century. Before that date, Muslim residents were limited to merchants and diplomats.[234] In the late 10th century, when al-Aswani came to Dongola, there was, despite being demanded in the Baqt, still no mosque; he and around 60 other Muslims had to pray outside of the city.[235] It is not until 1317, with the conversion of the throne hall by Abdallah Barshambu, when a mosque is firmly attested.[236] While the Jizya, the Islamic head tax enforced on non-Muslims, was established after the Mamluk invasion of 1276[237] and Makuria was periodically governed by Muslim kings since Abdallah Barshambu, the majority of the Nubians remained Christian.[238] The actual Islamization of Nubia began in the late 14th century, with the arrival of the first in a series of Muslim teachers propagating Islam.[239]

Economy

The main economic activity in Makuria was agriculture, with farmers growing several crops a year of

Important industries included the production of

Cattle were of great economic importance. It is possible that their breeding and marketing was controlled by the central administration. A great assemblage of 13th century cattle bones from Old Dongola has been linked with a mass slaughter by the invading Mamluks, who attempted to weaken the Makurian economy.[242]

Makurian trade was largely by barter as the state never adopted a

See also

Annotations

- ^ Theory I places that event at the time of the Sasanian invasion, theory II at the time between the first and second Arab invasion, i.e. 642 and 652, and the third at the turn of the seventh century.[28]

- ^ It has also been argued that the bishopric was not founded, but merely reestablished.[35]

- ^ Recently it has been suggested that the Arabs fought the Nubians not in Nubia, but in Upper Egypt, which remained a battle zone contested by both parties until the Arab conquest of Aswan in 652.[39]

- ^ Zakharias, presumably already quite powerful during the lifetime of Ioannes, was the husband of a sister of Ioannes. The matrilinear Nubian succession demanded that only the son of the king's sister could be the next king, hence making Zakharias an illegitimate king in contrast to his son Georgios.[64]

- ^ The claim of complete nakedness should not be taken for a fact, as it reflects an ancient stereotype.[131]

- ^ This might be a reference to the original three kingdoms of Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia, unless the author was implying the semi-autonomous status of Nobatia within Makuria.[131]

- ^ "Dalmatia" or "Damaltia" is probably an error for Tolmeita (ancient Ptolemais in Libya), which was a part of the patriarch of Alexandria's title: "archbishop of the great city of Alexandria and the city of Babylon (Cairo), and Nobadia, Alodia, Makuria, Dalmatia and Axioma (Axum)." It has been proposed that there was some confusion in the 1186 document between the titles of the king and the patriarch.[212]

Notes

- ^ Murray, John (1822). "Kingdom of Makuria". Dorota Dzierzbicka. 22 (22): 663–677.

- ^ Welsby 2002, p. 239.

- ^ Shinnie 1965, p. 266.

- ^ Adams 1977, p. 257.

- ^ Bowersock, Brown & Grabar 2000, p. 614.

- ^ Godlewski 1991, pp. 253–256.

- ^ a b Wyzgol & El-Tayeb 2018, p. 287.

- ^ Wyzgol & El-Tayeb 2018, Fig. 10.

- ^ Kołosowska & El-Tayeb 2007, p. 35.

- ^ Edwards 2004, p. 182.

- ^ Lohwasser 2013, pp. 279–285.

- ^ Godlewski 2014, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 42.

- ^ a b Godlewski 2014, p. 161.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 39.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Rilly 2008, pp. 214–217.

- ^ Godlewski 2013b, p. 5.

- ^ a b Godlewski 2013b, p. 7.

- ^ Godlewski 2013b, p. 17.

- ^ Godlewski 2014, p. 10.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 43.

- ^ Welsby 2002, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 58.

- ^ a b Welsby 2002, p. 33.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 58, 62–65.

- ^ Wyzgol 2018, p. 785.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 73–77.

- ^ a b c Godlewski 2013b, p. 90.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 77.

- ^ Godlewski 2013b, p. 85.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 76, note 84.

- ^ Godlewski 2013c, p. 90.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Welsby 2002, p. 88.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 254.

- ^ Welsby 2002, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Bruning 2018, pp. 94–96.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Godlewski 2013a, p. 91.

- ^ Welsby 2002, p. 69.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 68.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 70–72.

- ^ Ruffini 2012, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 73, 71.

- ^ Ruffini 2012, p. 7.

- ^ Welsby 2002, p. 68.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 70.

- ^ a b c Welsby 2002, p. 73.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 82.

- ^ Obłuski 2019, p. 310.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 83.

- ^ a b c Werner 2013, p. 84.

- ^ Adams 1977, p. 454.

- ^ Hasan 1967, p. 29.

- ^ Shinnie 1971, p. 45.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 86, note 37.

- ^ Smidt 2005, p. 128.

- ^ Godlewski 2013b, pp. 11, 39.

- ^ a b Fritsch 2018, pp. 290–291.

- ^ Godlewski 2002, p. 75.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 88.

- ^ Godlewski 2002, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 89.

- ^ Vantini 1975, p. 318.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 89–91.

- ^ a b Godlewski 2013a, p. 11.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 91.

- ^ Godlewski 2013b, p. 11.

- ^ Obłuski et al. 2013, Table 1.

- ^ Godlewski 2013b, p. 12.

- ^ Adams 1977, pp. 553–554.

- ^ Adams 1977, pp. 552–553.

- ^ Godlewski 2002, p. 84.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 94–95, note 50.

- ^ a b Godlewski 2002, p. 85.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 95.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 96.

- ^ Hasan 1967, p. 91.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 99–100, notes 16 and 17.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 101.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-6578-5.

- ^ a b c d Adams 1977, p. 456.

- ^ a b Werner 2013, p. 102.

- ^ Hasan 1967, p. 92.

- ^ Lepage & Mercier 2005, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Chojnacki 2005, p. 184.

- ^ Hesse 2002, pp. 18, 23.

- ^ Welsby 2014, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Welsby 2002, p. 89.

- ^ a b Lajtar 2009, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Danys & Zielinska 2017, pp. 182–184.

- ^ Lajtar & Ochala 2017, p. 264.

- ^ Welsby 2002, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Hendrickx 2018, p. 1, note 1.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 103.

- ^ Hendrickx 2018, p. 17.

- ^ Obłuski 2019, p. 126.

- ^ Lajtar & Ochala 2017, pp. 262–264.

- ^ Godlewski 2013a, pp. 671, 672.

- ^ a b Godlewski 2013a, p. 669.

- ^ Godlewski 2013a, pp. 672–674.

- ^ Wozniak 2014, pp. 939–940.

- ^ Wozniak 2014, p. 940.

- ^ Welsby 2002, p. 75.

- ^ Plumley 1983, p. 162.

- ^ Ruffini 2012, pp. 249–250.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 113.

- ^ Plumley 1983, pp. 162–163.

- ^ a b Ruffini 2012, p. 248.

- ^ Welsby 2002, p. 76.

- ^ a b Plumley 1983, p. 164.

- ^ Welsby 2002, p. 124.

- ^ Adams 1977, p. 522.

- ^ Grajetzki 2009, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Zurawski 2014, p. 84.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 117.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 117, note 16.

- ^ Gazda 2005, p. 93.

- ^ a b Werner 2013, p. 118.

- ^ a b Gazda 2005, p. 95.

- ^ Seignobos 2016, p. 554.

- ^ Seignobos 2016, p. 554, note 2.

- ^ Welsby 2002, p. 244.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 120–122.

- ^ a b Welsby 2002, p. 254.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 122–123.

- ^ von den Brincken 2014, pp. 45, 49–50.

- ^ von den Brincken 2014, p. 48.

- ^ a b Seignobos 2014, p. 1000.

- ^ Seignobos 2014, pp. 999–1000.

- ^ a b Łajtar & Płóciennik 2011, p. 110.

- ^ Seignobos 2012, pp. 307–311.

- ^ Simmons 2019, pp. 35–46.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 128.

- ^ Łajtar & Płóciennik 2011, p. 111.

- ^ Łajtar & Płóciennik 2011, pp. 114–116.

- ^ Borowski 2019, pp. 103–106.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 133.

- ^ a b Werner 2013, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Ruffini 2012, pp. 162–263.

- ^ Borowski 2019, p. 106.

- ^ Łajtar & Płóciennik 2011, p. 43.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 17.

- ^ Welsby 2002, p. 248.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 138.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 139–140, note 25.

- ^ Zurawski 2014, p. 82.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 140.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Ochala 2011, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Ruffini 2012, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 141–143.

- ^ Welsby 2002, pp. 248–250.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 144.

- ^ a b Welsby 2002, p. 253.

- ^ a b Werner 2013, p. 145.

- ^ Ruffini 2012, p. 9.

- ^ Lajtar 2011, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b Ruffini 2012, p. 256.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 149.

- .

- ^ Zurawski 2014, p. 85.

- ^ Adams 1977, p. 536.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 150.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 148, 157, note 68.

- ^ Welsby 2002, p. 256.

- ^ Adams 1977, pp. 557–558.

- ^ a b O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 29.

- ^ Adams 1977, p. 562.

- ^ Adams 1977, pp. 559–560.

- ^ Ochala 2011, p. 154.

- ^ Hesse 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 188, note 26.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 26, note 44.

- ^ Adams 1977, p. 495.

- ^ Welsby 2002, pp. 236–239.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 186.

- ^ Bechhaus-Gerst 1996, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 187.

- ^ Ochala 2014, p. 36.

- ^ a b Ochala 2014, p. 41.

- ^ Ochala 2014, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Ochala 2014, p. 37.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Ochala 2014, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 196.

- ^ Seignobos 2010, p. 14.

- ^ Zielinska & Tsakos 2019, p. 80.

- ^ Zielinska & Tsakos 2019, p. 93.

- ^ Godlewski 1991, pp. 255–256.

- ^ a b c Shinnie 1965, p. ?.

- ^ Shinnie 1978, p. 570.

- ^ a b Werner 2013, p. 248.

- ^ a b c Werner 2013, p. 344.

- ^ Ruffini 2012, p. 243.

- ^ Ruffini 2012, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Ruffini 2012, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 344–345.

- ^ Ruffini 2012, p. 235.

- ^ Ochała 2023, pp. 361–363.

- ^ Welsby 2002, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Godlewski 2013a, p. 97.

- ^ Williams et al. 2015, p. 135.

- ^ Welsby 2002, pp. 171–172.

- ^ a b Welsby 2002, p. 172.

- ^ Obłuski 2017, p. 373.

- ^ Shinnie 1978, p. 581.

- ^ Greisiger 2007, p. 204.

- ^ Hagen 2009, p. 117.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 243.

- ^ Adams 1991, p. 258.

- ^ Lajtar & Ochala 2021, pp. 371–372, 374–375.

- ^ Lajtar & Ochala 2021, pp. 375–376.

- ^ Jakobielski 1992, p. 211.

- ^ Zabkar 1963, p. ?.

- ^ Adams 1977, p. 440.

- ^ Vantini 1975, p. 616.

- ^ Adams 1977, p. 441.

- ^ "Information on Medieval Nubia". Archived from the original on 2018-01-03. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ^ Shinnie 1978, p. 583.

- ^ Adams 1977, p. 472.

- ^ Adams 1977, p. 478.

- ^ al-Suriany 2013, p. 257.

- ^ Godlewski 2013b, p. 101.

- ^ a b Welsby 2002, p. 106.

- ^ a b Adams 1977, p. 468.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 155.

- ^ Seignobos 2010, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Khan 2013, p. 147.

- ^ Welsby 2002, p. 107.

- ^ Godlewski 2013a, p. 117.

- ^ Holt 2011, p. 16.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 71, note 44.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 137–140.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Shinnie 1978, p. 556.

- ^ Jakobielski 1992, p. 207.

- ^ Osypinska 2015, p. 269.

References

- Adams, William Y. (1977). Nubia: Corridor to Africa. Princeton: ISBN 978-0-7139-0579-3.

- Adams, William Y. (1991). "The United Kingdom of Makouria and Nobadia: A Medieval Nubian Anomaly". In W.V. Davies (ed.). Egypt and Africa: Nubia from Prehistory to Islam. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-0962-6.

- al-Suriany, Bigoul (2013). "Identification of the Monastery of the Nubians in Wadi al-Natrun". In Gawdat Gabra; Hany N. Takla (eds.). Christianity and Monasticism in Aswan and Nubia. Saint Mark Foundation. pp. 257–264. ISBN 978-9774167645.

- Bechhaus-Gerst, Marianne (1996). Sprachwandel durch Sprachkontakt am Beispiel des Nubischen im Niltal (in German). Köppe. ISBN 3-927620-26-2.

- Beckingham, C.F.; Huntingford, G.W.B. (1961). The Prester John of the Indies. Cambridge: Hakluyt Society.

- Borowski, Tomasz (2019). "Placed in the Midst of Enemies? Material Evidence for the Existence of Maritime Cultural Networks Connecting Fourteenth-Century Famagusta with Overseas Regions in Europe, Africa and Asia". In Walsh, Michael J. K. (ed.). Famagusta Maritima. Mariners, Merchants, Pilgrims and Mercenaries. Brill. pp. 72–112. ISBN 9789004397682.

- Bowersock, G. W.; Brown, Peter; Grabar, Oleg (2000). "Nubian language". A Guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press.

- Bruning, Jelle (2018). The Rise of a Capital: Al-Fusṭāṭ and Its Hinterland, 18-132/639-750. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-36636-7.

- Burns, James McDonald (2007). A History of Sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 418. ISBN 978-0-521-86746-7.

- Chojnacki, Stanislaw (2005). "Wandgemälde, Ikonen, Manuskripte, Kreuze und anderes liturgisches Gerät". In Walter Raunig (ed.). Das christliche Äthiopien. Geschichte, Architektur, Kunst (in German). Schnell und Steiner. pp. 171–250. ISBN 9783795415419.

- Danys, Katarzyna; Zielinska, Dobrochna (2017). "Alwan art. Towards an insight into the aesthetics of the Kingdom of Alwa through the painted pottery decoration". Sudan&Nubia. 21: 177–185. ISSN 1369-5770.

- Edwards, David (2004). The Nubian Past: An Archaeology of the Sudan. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415369879.

- Fritsch, Emmanuel (2018). "The Origins and Meanings of the Ethiopian Circular Church". In Robin Griffith-Jones, Eric Fernie (ed.). Tomb and Temple. Re-Imagining the Sacred Buildings of Jerusalem. Boydell. pp. 267–296. ISBN 9781783272808.

- Gazda, M (2005). "Mameluke invasions on Nubia in the 13th Century. Some Thoughts on Political Interrelations in the Middle East". Gdansk African Reports. 3. Gdansk Archaeological MuseumGdansk Archaeological Museum. ISSN 1731-6146.

- Godlewski, Wlodzimierz (1991). "The Birth of Nubian Art: Some Remarks". In W.V. Davies (ed.). Egypt and Africa: Nubia from Prehistory to Islam. London: British Museum. ISBN 978-0-7141-0962-6.

- Godlewski, Wlodzimierz (2002). "Introduction to the Golden Age of Makuria". Africana Bulletin. 50: 75–98.

- Godlewski, Wlodzimierz (2013a). "Archbishop Georgios of Dongola. Socio-political change in the kingdom of Makuria in the second half of the 11th century" (PDF). Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean. 22: 663–677.

- Godlewski, Włodzimierz (2013b). Dongola-ancient Tungul. Archaeological guide (PDF). Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw. ISBN 978-83-903796-6-1.

- Godlewski, Wlodzimierz (2013c). "The Kingdom of Makuria in the 7th century. The struggle for power and survival". In Christian Julien Robin; Jérémie Schiettecatte (eds.). Les préludes de l'Islam. Ruptures et continuités. De Boccard. pp. 85–104. ISBN 978-2-7018-0335-7.

- Godlewski, Włodzimierz (2014). "Dongola Capital of early Makuria: Citadel – Rock Tombs – First Churches" (PDF). In Angelika Lohwasser; Pawel Wolf (eds.). Ein Forscherleben zwischen den Welten. Zum 80. Geburtstag von Steffen Wenig. Mitteilungen der Sudanarchäologischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin E.v. ISSN 0945-9502.

- Grajetzki, Wolfram (2009). "Das Ende der christlich-nubischen Reiche" (PDF). Internet-Beiträge zur Ägyptologie und Sudanarchäologie. X.

- Greisiger, Lutz (2007). "Ein nubischer Erlöser-König: Kus in syrischen Apokalypsen des 7. Jahrhunderts" (PDF). In Sophia G. Vashalomidze, Lutz Greisiger (ed.). Der christliche Orient und seine Umwelt.

- Hagen, Joost (2009). "Districts, Towns and Other Locations of Medieval Nubia and Egypt, Mentioned in the Coptic and Old Nubian Texts from Qasr Ibrim". Sudan & Nubia. 13: 114–119.

- Hasan, Yusuf Fadl (1967). The Arabs and the Sudan. From the seventh to the early sixteenth century. OCLC 33206034.

- Hesse, Gerhard (2002). Die Jallaba und die Nuba Nordkordofans. Händler, Soziale Distinktion und Sudanisierung. Lit. ISBN 3825858901.

- Hendrickx, Benjamin (2018). "The Letter of an Ethiopian King to King George II of Nubia in the framework of the ecclesiastic correspondence between Axum, Nubia and the Coptic Patriarchate in Egypt and of the events of the 10th Century AD". Pharos Journal of Theology: 1–21. ISSN 2414-3324.

- Holt, P. A. (2011). A History of the Sudan. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-1405874458.

- Jakobielski, S (1992). "Christian Nubia at the Height of its Civilization". UNESCO General History of Africa. Volume III. ISBN 978-0-520-06698-4.

- Khan, Geoffrey (2013). "The Medieval Arabic Documents from Qasr Ibrim". Qasr Ibrim, between Egypt and Africa. Peeters. pp. 145–156.

- Kropacek, L. (1997). "Nubia from the late twelfth century to the Funj conquest in the early fifteenth century". UNESCO General History of Africa. Volume IV.

- Kołosowska, Elżbieta; El-Tayeb, Mahmoud (2007). "Excavations at the Kassinger Bahri Cemetery Sites HP45 and HP47". Gdańsk Archaeological Museum African Reports. 5: 9–37.

- Lev, Yaacov (1999). Saladin in Egypt. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-11221-6.

- Łajtar, Adam; Płóciennik, Tomasz (2011). "A man from Provence on the Middle Nile: A graffito in the Upper Church at Banganarti". In Łajtar, Adam; van der Vliet, Jacques (eds.). Nubian Voices. Studies in Christian Nubian Culture. Taubenschlag. pp. 95–120. ISBN 978-83-925919-4-8.

- Lajtar, Adam; Ochala, Grzegorz (2017). "An Unexpected Guest in the Church of Sonqi Tino". Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies. 4: 257–268. .

- Lajtar, Adam; Ochala, Grzegorz (2021). "A Christian King in Africa. The Image of Christian Nubian Rulers in Internal and External Sources". The Good Christian Ruler in the First Millennium. pp. 361–380.

- Lajtar, Adam (2009). "Varia Nubica XII-XIX" (PDF). The Journal of Juristic Papyrology (in German). XXXIX: 83–119. ISSN 0075-4277.

- Lajtar, Adam (2011). "Qasr Ibrim's last land sale, AD 1463 (EA 90225)". Nubian Voices. Studies in Christian Nubian Culture.

- Lepage, Clade; Mercier, Jacques (2005). Les églises historiques du Tigray. The Ancient Churches of Tigrai. Editions Recherche sur les Civilisations. ISBN 2-86538-299-0.

- Lohwasser, Angelika (2013). "Das „Ende von Meroe". Gedanken zur Regionalität von Ereignissen". In Feder, Frank; Lohwasser, Angelika (eds.). Ägypten und sein Umfeld in der Spätantike. Vom Regierungsantritt Diokletians 284/285 bis zur arabischen Eroberung des Vorderen Orients um 635-646. Akten der Tagung vom 7.-9.7.2011 in Münster. Harrassowitz. pp. 275–290. ISBN 9783447068925.

- Martens-Czarnecka, Malgorzata (2015). "The Christian Nubia and the Arabs". Studia Ceranea. 5: 249–265. ISSN 2084-140X.

- McHugh, Neil (1994). Holymen of the Blue Nile: The Making of an Arab-Islamic Community in the Nilotic Sudan. ISBN 0810110695.

- Michalowski, K. (1990). "The Spreading of Christianity in Nubia". UNESCO General History of Africa. Vol. II. University of California. ISBN 978-0-520-06697-7.

- Obłuski, Arthur (2017). "The winter seasons of 2013 and 2014 in the Ghazali monastery". Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean. 26/1.

- Obłuski, Arthur (2019). The Monasteries and Monks of Nubia. The Taubenschlag Foundation. ISBN 978-83-946848-6-0.

- Obłuski, Artur; Godlewski, Włodzimierz; Kołątaj, Wojciech; et al. (2013). "The Mosque Building in Old Dongola. Conservation and revitalization project" (PDF). Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean. 22. Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw: 248–272. ISSN 2083-537X.

- Ochala, Grzegorz (2011). "A King of Makuria in Kordofan". In Adam Lajtar, Jacques van der Vliet (ed.). Nubian Voices. Studies in Christian Nubian Culture. Journal of Juristic Papyrology. pp. 149–156.

- Ochala, Grzegorz (2014). "Multilingualism in Christian Nubia: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches". Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies. 1. Journal of Juristic Papyrology. ISBN 978-0692229149.

- Ochała, Grzegorz (2023). "Female diaconate in medieval Nubia: Evidence from a wall inscription from Faras". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 86 (2): 351–365. .

- O'Fahey, R. S.; Spaulding, Jay (1974). Kingdoms of Sudan. Methuen Young Books.

- Osypinska, Marta (2015). "Animals: archaeozoological research on the osteological material from the Citadel". In Włodzimierz Godlewski; Dorota Dzierzbicka (eds.). Dongola 2012-2014. Fieldwork, conservation and site management. Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw. pp. 259–271. ISBN 978-83-903796-8-5.

- Plumley, J. Martin (1983). "Qasr Ibrim and Islam". Études et Travaux. XII: 157–170.

- Rilly, Claude (2008). "Enemy brothers: Kinship and relationship between Meroites and Nubians (Noba)". Between the Cataracts: Proceedings of the 11th Conference of Nubian Studies, Warsaw, 27 August – 2 September 2006. Part One. PAM. pp. 211–225. ISBN 978-83-235-0271-5.

- Ruffini, Giovanni R. (2012). Medieval Nubia. A Social and Economic History. Oxford University.

- Ruffini, Giovanni (2013). "Newer light on the Kingdom of Dotawo". In J. van der Vliet; J. L. Hagen (eds.). Qasr Ibrim, between Egypt and Africa. Studies in Cultural Exchange (NINO Symposium, Leiden, 11–12 December 2009). Peeters. pp. 179–191. ISBN 9789042930308.

- Seignobos, Robin (2010). "La frontière entre le bilād al-islām et le bilād al-Nūba : enjeux et ambiguïtés d'une frontière immobile (VIIe-XIIe siècle)". Afriques (in French). 02. .

- Seignobos, Robin (2012). "The other Ethiopia: Nubia and the crusade (12th-14th century)". Annales d'Éthiopie. 27. Table Ronde: 307–311. ISSN 0066-2127.

- Seignobos, Robin (2014). "Nubia and Nubians in Medieval Latin Culture. The Evidence of Maps (12th-14th cent.)". In Anderson, Julie R; Welsby, Derek (eds.). The Fourth Cataract and Beyond: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference for Nubian Studies. Peeters Pub. pp. 989–1005. ISBN 978-9042930445.

- Seignobos, Robin (2016). "La liste des conquêtes nubiennes de Baybars selon Ibn Šadd ād (1217 – 1285)" (PDF). In A. Łajtar; A. Obłuski; I. Zych (eds.). Aegyptus et Nubia Christiana. The Włodzimierz Godlewski Jubilee Volume on the Occasion of his 70 th Birthday (in French). Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology. pp. 553–577. ISBN 9788394228835.

- Shinnie, P.L. (1971). "The Culture of Medieval Nubia and its Impact on Africa". In Yusuf Fadl Hasan (ed.). Sudan in Africa. Khartoum University. pp. 42–50. OCLC 248684619.

- Shinnie, P.L. (1996). Ancient Nubia. London: Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7103-0517-6.

- Shinnie, P.L. (1978). "Christian Nubia.". In J.D. Fage (ed.). The Cambridge History of Africa. Volume 2. Cambridge: ISBN 978-0-521-21592-3.

- Shinnie, P.L. (1965). "New Light on Medieval Nubia". Journal of African History. VI, 3.

- Simmons, Adam (2019). "The Changing Depiction of the Nubian king in Crusader Songs in an Age of Expanding Knowledge". In Benjamin Weber (ed.). Croisades en Africa. Les expeditions occidentales à destination du continent africain, XIIIe-VVIe siècles. Presses universitaires du Midi Méridiennes. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-2810705573.

- Smidt, W. (2005). "An 8th century Chinese fragment on the Nubian and Abyssinian kingdoms". In Walter Raunig; Steffen Wenig (eds.). Afrikas Horn. Harrassowitz. pp. 124–136.

- Spaulding, Jay (1995). "Medieval Christian Nubia and the Islamic World: A Reconsideration of the Baqt Treaty". International Journal of African Historical Studies. XXVIII, 3.

- Vantini, Giovanni (1970). The Excavations at Faras.

- Vantini, Giovanni (1975). Oriental Sources concerning Nubia. Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften. OCLC 174917032.

- von den Brincken, Anna-Dorothee (2014). "Spuren Nubiens in der abendländischen Universalkartographie im 12. bis 15. Jahrhundert". In Dlugosz, Magdalena (ed.). Vom Troglodytenland ins Reich der Scheherazade. Archäologie, Kunst und Religion zwischen Okzident und Orient (in German). Frank & Timme. pp. 43–52. ISBN 9783732901029.

- Welsby, Derek (2002). The Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia. Pagans, Christians and Muslims along the Middle Nile. The British Museum. ISBN 0714119474.

- Welsby, Derek (2014). "The Kingdom of Alwa". In Julie R. Anderson; Derek A. Welsby (eds.). The Fourth Cataract and Beyond: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference for Nubian Studies. ISBN 978-90-429-3044-5.

- Werner, Roland (2013). Das Christentum in Nubien. Geschichte und Gestalt einer afrikanischen Kirche. Lit.

- Williams, Bruce B.; Heidorn, Lisa; Tsakos, Alexander; Then-Obłuska, Joanna (2015). "Oriental Institute Nubian Expedition (OINE)" (PDF). In Gil J. Stein (ed.). The Oriental Institute 2014–2015 Annual Report. Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. pp. 130–143. ISBN 978-1-61491-030-5.

- Wozniak, Magdalena (2014). "Royal Iconography: Contribution to the Sudy of Costume". The Fourth Cataract and Beyond. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference for Nubian Studies. Leuven. pp. 929–941.

- Wyzgol, Maciej; El-Tayeb, Mahmoud (2018). "Early Makuria Research Project. Excavations at Tanqasi: first season in 2018". Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean. 27: 273–288. ISSN 1234-5415.

- Wyzgol, Maciej (2018). "A decorated bronze censer from the Cathedral in Old Dongola". Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean. 26/1. Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology: 773–786. S2CID 55185622.

- Zabkar, Louis (1963). "The Eparch of Nobatia as King". Journal of Near Eastern Studies.

- Zielinska, Dobrochna; Tsakos, Alexandros (2019). "Representations of Archangel Michael in Wall Paintings from Medieval Nubia". In Ingvild Sælid Gilhus; Alexandros Tsakos; Marta Camilla Wright (eds.). The Archangel Michael in Africa. History, Cult and Persona. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 79–94. ISBN 9781350084711.

- Zurawski, Bogdan (2014). Kings and Pilgrims. St. Raphael Church II at Banganarti, mid-eleventh to mid-eighteenth century. IKSiO. ISBN 978-83-7543-371-5.

Further reading

- Eger, Jana (2019). "The Land of Tari and Some New Thoughts on Its Location". The Archaeology of Medieval Islamic Frontiers: From the Mediterranean to the Caspian Sea. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-1607328780.

- Godlweski, Wlodzimierz (2004). "The Rise of Makuria (late 5th-8th cent.)". In Timothy Kendall (ed.). Nubian Studies. 1998. Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference of Nubian Studies, August 20–26. Northeastern University. pp. 52–72. ISBN 0976122103.

- Innemée, Karel C. (2016). Monks and bishops in Old Dongola, and what their costumes can tell us.

- Jakobielski, Stefan; et al., eds. (2017). Pachoras, Faras, The wall paintings from the Cathedrals of Aetios, Paulos and Petros. University of Warsaw. ISBN 978-83-942288-7-3.

- Martens-Czarnecka, Małgorzata (2011). The Wall Paintings from the Monastery on Kom H in Dongola. Warsaw University Press. ISBN 978-83-235-0923-3.

- Seignobos, Robin (2015). "Les évêches Nubiens: Nouveaux témoinages. La source de la liste de Vansleb et deux autres textes méconnus". In Adam Lajtar; Grzegorz Ochala; Jacques van der Vliet (eds.). Nubian Voices II. New Texts and Studies on Christian Nubian Culture (in French). Raphael Taubenschlag Foundation. ISBN 978-8393842575.

- Seignobos, Robin (2016). "La liste des conquêtes nubiennes de Baybars selon Ibn Šadd ād (1217 – 1285)" (PDF). In A. Łajtar; A. Obłuski; I. Zych (eds.). Aegyptus et Nubia Christiana. The Włodzimierz Godlewski Jubilee Volume on the Occasion of his 70 th Birthday (in French). Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology. pp. 553–577. ISBN 9788394228835.

- Then-Obłuska, Joanna (2017). "Royal ornaments of a late antique African kingdom, Early Makuria, Nubia (AD 450–550). Early Makuria Research Project". Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean. 26/1: 687–718.

- Baadj, Amar (2014). "The Political Context of the Egyptian Gold Crisis during the Reign of Saladin". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 47 (1): 121–138. JSTOR 24393332.

- Wozniak, Magdalena. L'influence byzantine dans l'art nubien.

- Wozniak, Magdalena. Rayonnement de Byzance: Le costume royal en Nubie (Xe s.).

- Wozniak, Magdalena (2016). The chronology of the eastern chapels in the Upper Church at Banganarti. Some observations on the genesis of "apse portraits" in Nubian royal iconography.