May Thirtieth Movement

| Part of People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949. |

| Outline of the Chinese Civil War |

|

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

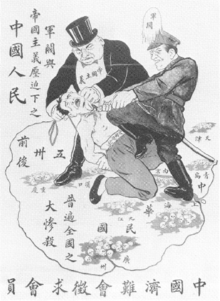

The May Thirtieth Movement (

Roots of the Incident

In the aftermath of the 1924

Alongside public grief at the recent death of China's Republican hero

In early months of 1925, conflicts and strikes on those matters intensified.

A week later a group of Chinese students, heading for Ku's public "state" funeral and carrying banners, were arrested while traveling through the International Settlement. With their trial set for May 30, various student organisations convened in the days before and decided to hold mass demonstrations across the International Settlement and outside the

The Nanjing Road Incident

On the morning of May 30, 1925, just after the trial of the arrested students began,

After forcing protesters out of the charge room, a picket of police (there was only a skeleton staff of approximately two dozen officers overall, predominantly Sikh and Chinese, with three white officers) was set up to prevent demonstrators from entering the station. In the minutes before the shooting, police and some witnesses reported that cries of "kill the foreigners" were raised as the demonstration turned violent.[6][7] Inspector Edward Everson, station commander and the highest-ranking officer on the scene (as the police commissioner K.J. McEuen had not let early warnings of public demonstrations interfere with his attendance at the city's Race Club) eventually shouted, "Stop! If you do not stop I will shoot!" in Wu. A few seconds later, at 3:37 pm, and as the crowd was within six feet of the station entrance, he fired into the crowd with his revolver. The Sikh and Chinese policemen then also opened fire, discharging some 40 rounds. At least four demonstrators were killed at the scene, with another five dying later of their injuries. At least 14 injured were hospitalized, with many others wounded.[8]

Strikes and martial law

On Sunday, May 31, crowds of students posted bills and demanded shops refuse to sell foreign goods or serve non-Chinese. They then convened at the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, where they gave a list of demands, including punishment of the officers involved in the shooting, an end to extraterritoriality and closure of the Shanghai International Settlement. The president of the Chamber of Commerce was away, but eventually his deputy agreed to press for the demands to be carried out. Nevertheless, he subsequently sent a message to the foreign Municipal Council that his consent was given under duress.

The Municipal Council declared a state of martial law on Monday, June 1, calling up the Shanghai Volunteer Corps militia and requesting foreign military assistance to carry out raids and protect vested interests. Over the next month Shanghai businesses and workers went on strike, and there were sporadic outbreaks of demonstration and violence. Trams and foreigners were attacked, and there was looting of shops that refused to uphold the boycott of foreigners. Servants to foreigners refused to work, and almost a third of Chinese police failed to turn up for their shifts. The gas works, electricity station, waterworks and telephone exchange became entirely run by Western volunteers.

The numbers of Chinese killed and injured in the May 30 Movement's riots vary: figures normally vary between 30 and 200 dead, with hundreds injured. Policemen, firemen and foreigners were also injured, some seriously, and one Chinese police constable was killed.

Aftermath

The incident shocked and galvanized China, and the strikes and boycotts, coupled with further violent demonstrations and riots, quickly spread across the country, bringing foreign economic interests to a near standstill.

The target of public ire moved from the Japanese (for the death of Ku Chen-Hung) to the British, and

Two investigations into the events of May 30 were ordered, one by Chinese authorities and one by international appointees, Justice Finley Johnson (presiding), Judge of the Court of First Instance in the Philippines (representing America), Sir Henry Gollan, Chief Justice of Hong Kong (representing Britain) and Justice Kisaburo Suga of the Hiroshima Court of Appeal (representing Japan). The Chinese authorities refused to participate in the international investigation, which found 2-1 that the shooting justifiable. Only the Justice Finley from America disagreed and recommended sweeping changes, including the retirement of the chief of the Settlement Police, Commissioner McEuen, and Inspector Everson. Their forced resignation in late-1925 would be the only official result of the inquiry.[citation needed]

By November, with

The May Thirtieth events caused the transfer of the Muslim Chengda College and Imam (Ahong) Ma Songting to Beijing.[10]

The May Thirtieth Movement began a period of increasing radicalization and militancy among China's industrial workers, students, and progressive intellectuals.[11]: 61 It resulted in a major period of growth for the CCP.[12]: 56 It also helped boost the Kuomintang to national hegemony.[12]: 56

Memorial

In the 1990s, the May Thirtieth Movement Monument was installed at People's Park.[citation needed]

See also

- History of the Republic of China

- May Fourth Movement

- Republic of China Armed Forces

- Shanghai massacre

- Warlord Era

References

- ISBN 978-0-313-32383-6.

- ^ a b Waldron, Arthur, (1991) From War to Nationalism: China's Turning Point, p. 5.

- ^ Ku, Hung-Ting [1979] (1979). Urban Mass Movement: The May Thirtieth Movement in Shanghai. Modern Asian Studies, Vol.13, No.2. pp.197-216

- ^ B.L [1936] (Jul 15, 1936). Shanghai at Last Gets Factory Inspection Law. Far Eastern Survey, Vol.5, No.15.

- ^ Ku, Hung-Ting [1979] (1979). Urban Mass Movement: The May Thirtieth Movement in Shanghai. Modern Asian Studies, Vol.13, No.2. pp.201

- ^ a b Potter, Edna Lee (1940). News Is My Job: A Correspondent in War-Torn China. Macmillan publishing. p. 198

- ISBN 0-7139-9684-6. p. 165

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7425-3422-3. p. 100

- ^ http://www.yalebooks.co.uk/yale/results.asp?SF1=author&ST1=Niv%20Horesh&. Retrieved May 13, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)[dead link] - ISBN 978-0-295-80055-4.

- ISBN 9780231204477.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-350-23394-2.