Megaherbivore

Megaherbivores (Greek

Extant megaherbivores are

Definition

Megaherbivores are large herbivores that weigh more than 1 ton when fully grown.[2] They also include large marine herbivores.[1] They are a type of megafauna (>45 kg), and are the largest animals on land.[3]

Evolution

Permian

Megaherbivores first evolved in the

Triassic

Lisowicia was the last dicynodont that lived and became extinct in the Late Triassic.[5] Some scientists have proposed that there was never a Triassic–Jurassic extinction event, but others argue that the extinctions may have occurred earlier. Flood basalts are thought to be the primary driver of the extinctions, towards the end of the Triassic.[13] [14]

| Amniota |

| ||||||||||||

Jurassic

The taxonomic structure then switched to

Cretaceous

Dinosauria

|

|

From the Triassic to the Cretaceous, a diverse assemblage of megaherbivorous dinosaurs, such as sauropods,[17] occupied different ecological niches. Based on their dentition, ankylosaurs may have mainly consumed succulent plants, as opposed to nodosaurs, which were mainly browsers. It is thought that ceratopsids fed on rugged vegetation, due to their jaw being designed for a crushing effect. Studies on hadrosaur dentition concluded that they primarily fed on fruits.[18]

Paleogene

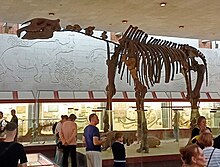

Following the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction, megaherbivore dinosaurs were extirpated from the face of the earth. One mechanism is thought to have played a major role: an extraterrestrial impact event in the Yucatán Peninsula.[19] For about 25 million years, the earth was void of large terrestrial herbivores that weighed more than 1 tonne. After this period, small mammalian species evolved into large herbivores. Herbivorous mammals had evolved to megaherbivore size across every continent around 40 mya.[2] The largest of these animals were Paraceratheriidae and Proboscidea.[20] Other taxa included Brontotheriidae.[21] The Sirenia, aquatic megaherbivores, such as Dugongidae, Protosirenidae, and Prorastomidae were present in the Eocene.[22] They inhabited every major landmass in the Cenozoic and Pleistocene before the arrival of humans.[4]

Pleistocene

There were around 50 different species by the Late Pleistocene:[3]

Mammalia

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Diprotodon was present across the entire Australian continent by the Late Pleistocene.[23] Glyptodonts were grazing herbivores. Like many other xenarthrans, they had no incisor or canine teeth, but had cheek teeth that would have been able to grind up tough vegetation. [24] Ground sloths were herbivores, with some being browsers,[25] others grazers,[26] and some intermediate between the two as mixed feeders.[27] Mammoths, like modern day elephants, have hypsodont molars. These features also allowed mammoths to live an expansive life because of the availability of grasses and trees.[28]

Today, nine of the 50 species persist. The Americas saw the worst decline in megaherbivores, with all 27 species going extinct.[3]

The

Recent

| Placentalia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There are nine extant species of megaherbivores, found in Africa and Asia.[35][36] They include elephants, rhinos, hippos and giraffes.[35][37]: 1 [38] Elephants belong to the order Proboscidea, that has been around since the late Paleocene.[39] Hippopotamuses are the closest living relatives to cetaceans. Soon after the common ancestor of whales and hippos diverged from even-toed ungulates, the lineages of cetaceans and hippopotamuses split apart.[40][41] Giraffidae are a sister taxon to Antilocapridae, with an estimated split of more than 20 million years ago, according to a 2019 genome study.[42] Rhinoceroses may originate from Hyrachyus, an animal whose remains dates back to the late Eocene.[37]: 17

Megaherbivores and other large herbivores are becoming less common throughout their natural distribution, which is having an impact on animal species within the ecosystem. This is mainly attributed to the destruction of their natural environment, agriculture, overhunting, and human invasion of their habitats.[43][44] As a consequence of their slow reproductive rate and the preference for targeting larger species, overexploitation poses the greatest threat to megaherbivores. As time progresses, it is thought that the situation will only grow worse.[43]

Ecology of recent megaherbivory

Browsers and grazers

Living species exhibit the following adaptations: they have dietary tolerance, have a strong effect on vegetation and with the exception of calves, they face little threat from predators.[45][46][47]

Elephants and Indian rhinoceroses exhibit both grazing and browsing feeding habits. The hippopotamus and white rhinoceros prefer

Due to their size, megaherbivores can defoliate the landscape. Because of this, they are considered keystone species in their environment.[49] Megaherbivores affect the composition of plant species, which alters the movement and exchange of inorganic and organic matter back into the production of matter. They can open up areas through feeding behavior, which over time clears vegetation. The number of seeds that megaherbivores spread is greater than that of other frugivores.[4] Megaherbivore grazers, like the white rhino, have a profound impact on short grass. In one study, short grass became more infrequent after the elimination of white rhinos, affecting smaller grazers in the process.[48] Their metabolic rate is lethargic, and as a result, digestion is slowed. During this prolonged digestion period, high-fiber plant matter is disintegrated.[38]

In a 2018 study, it was concluded that megaherbivores were not affected by the "landscape of fear," a landscape in which prey avoid certain hot-spot predation areas, thereby altering predator-frightened trophic cascades. Their feces were most apparent in closed, dense areas, indicating that they distribute resources to risky areas in this "landscape of fear".[50]

Interspecific interactions

Most megaherbivore species are too big and powerful for most predators to kill.

Giraffes may flee or act in a non-aggressive manner, while white rhinos typically do not react to the presence of predators. Black and Indian rhinoceroses, elephants, and hippopotamuses react strongly to predators.[37]: 124–131

Adaptations of extant megaherbivores

Size

Elephants are the largest members, weighing between 2.5–6.0 tons. Indian rhinos, white rhinos and hippos usually weigh between 1.4–2.3 tons. The Javan and black rhino average 1–1.3 tons in weight. Giraffes are the smallest members, with a general weight range of 0.8–1.2 tons.[37]: 14 [56]

K-selection

Extant megaherbivores are

Reproduction

When females enter estrus, males will attempt to attract and mate with them. Breeding opportunities may be influenced by the hierarchical system of males. Giraffes and elephants mate for a relatively short time, while rhinos and hippos have a mating session lasting an extended period of time. Females have long gestation periods, between 8 and 22 months. Intervals between births vary between species, but the overall range is 1.3 to 4.5 years.[37]: 116–124

They usually give birth to a single calf. Calves are born helpless and heavily rely on females for food and protection. As they get older, the calf begins weaning while still suckling. When they reach juvenility, they are able to fend for themselves, but only to a certain extent. Females typically separate from their offspring by chasing them. Despite this, females may continue to interact with their progeny even after weaning.[37]: 133

Lifespan and mortality

Hippopotamuses and rhinoceroses can live to be 40 years old, while elephants can live longer than 60 years.[52] Giraffes have a lifespan of around 25 years.[37]: 158

Around 2 to 5% of adult megaherbivores die each year. Males are more likely than females to die from wounds sustained during disputes. Giraffes are the most preyed-upon megaherbivore species. Occasionally, in times of drought, populations may significantly reduce, with calves being the most impacted.[37]: 158

See also

References

- ^ a b "Megaherbivore". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

Tropical seagrass meadows support a diversity of grazers spanning the meso-, macro-, and megaherbivore scales.

- ^ PMID 35414237.

- ^ PMID 26811442.

- ^ ISSN 2296-701X.

- ^ PMID 30467179.

- PMID 33875588.

- PMID 24287957.

- ISSN 0024-4066.

- PMID 26601239.

- S2CID 240076553.

- PMID 33837195.

- S2CID 87789173.

- ^ Barras, Colin (8 January 2024). "The mass extinction that might never have happened". New Scientist. Retrieved 2024-01-08.

- S2CID 91926999.

- PMID 35433123.

- S2CID 53619160.

- S2CID 259000968.

- PMID 24918431.

- PMID 25065505.

- S2CID 206989975.

- S2CID 258618428.

- .

- ISSN 1040-6182.

- ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- .

- S2CID 239902623.

- S2CID 254701351.

- .

- .

- PMID 24649488.

- ISBN 978-0-8165-1759-6.

- ISBN 978-0-300-00755-8.

- ISBN 978-0-8165-1100-6.

- ISBN 0-632-09120-7.

- ^ a b 'Wildlife' Review. U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. 1989.

- S2CID 235698268.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-42637-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-59726-609-3.

- PMID 19549873.

- PMID 9159931.

- PMID 15677331.

- PMID 31221828.

- ^ PMID 26601172.

- S2CID 233926684.

- ISBN 9780123847201.

- S2CID 206989975.

- ISSN 0141-6707.

- ^ ISBN 978-91-7760-966-7.

- PMID 24649488.

- PMID 30033334.

- ISSN 1545-1542.

- ^ ISBN 978-94-009-2605-9.

- S2CID 86371484.

- PMID 24026347.

- ISBN 978-0-520-08085-0.

- S2CID 84294169.

- S2CID 201756810.

- S2CID 265507842.

- ^ a b Rafferty, John P. "K-selected species". Britannica. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ISSN 0952-8369.