Largest and heaviest animals

The largest animal currently alive is the

In 2023, paleontologists estimated that the extinct whale

The African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana) is the largest living land animal. A native of various open habitats in sub-Saharan Africa, males weigh about 6.0 tonnes (13,200 lb) on average.[11] The largest elephant ever recorded was shot in Angola in 1974. It was a male measuring 10.67 metres (35.0 ft) from trunk to tail and 4.17 metres (13.7 ft) lying on its side in a projected line from the highest point of the shoulder, to the base of the forefoot, indicating a standing shoulder height of 3.96 metres (13.0 ft). This male had a computed weight of 10.4 to 12.25 tonnes.[1]

Heaviest living animals

The heaviest living animals are all whales. Since no scale can accommodate the whole body of a large whale, most have been weighed by parts.

| Rank | Animal | Average mass [tonnes] |

Maximum mass [tonnes] |

Average total length [m (ft)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Blue whale[12] | 110[13] | 190[1] | 24 (79)[14] |

| 2 | North Pacific right whale | 60[15] | 120[1] | 15.5 (51)[13] |

| 3 | Southern right whale | 58[13] | 110[16] | 15.25 (50)[13] |

| 4 | Fin whale | 57[13] | 120[16] | 19.5 (64)[13] |

| 5 | Bowhead whale | 54.5[13][17] | 120[1] | 15 (49)[13] |

| 6 | North Atlantic right whale | 54[13][18] | 110[16][19] | 15 (49)[13][19] |

| 7 | Sperm whale | 31.25[13][20] | 57[21] | 13.25 (43.5)[13][20] |

| 8 | Humpback whale | 29[13][22] | 48[23] | 13.5 (44)[13] |

| 9 | Sei whale | 22.5[13] | 45[24] | 14.8 (49)[13] |

| 10 | Gray whale | 19.5[13] | 45[25] | 13.5 (44)[13] |

Heaviest terrestrial animals

The heaviest land animals are all mammals. The African elephant is now listed as two species, the African bush elephant and the African forest elephant, as they are now generally considered to be two separate species.[26]

| Rank | Animal | Average mass [tonnes] |

Maximum mass [tonnes] |

Average total length [m (ft)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | African bush elephant | 6[27][28] | 10.4[29] | 7 (23)[30] |

| 2 | Asian elephant | 4.5[1][31] | 8.15[1] | 6.8 (22.3)[31] |

| 3 | African forest elephant | 2.7[32] | 6.0[32] | 6.2 (20.3)[33] |

| 4 | White rhinoceros | 2[34][35] | 4.5[36] | 4.4 (14.4)[37] |

| 5 | Indian rhinoceros | 1.9[38][39] | 4.0[40] | 4.2 (13.8)[41] |

| 6 | Hippopotamus | 1.8[42][43] | 4.5[44] | 5.05 (16.5)[45] |

| 7 | Black rhinoceros | 1.1[46] | 2.9[47] | 4 (13.1)[48] |

| 8 | Javan rhinoceros | 1.75[49][50] | 2.3[51] | 3.8 (12.5)[52] |

| 9 | Giraffe | 1.0[1] | 2[53] | 5.15 (16.9)[54] |

| 10 | Gaur | 0.95[55] | 1.5[55] | 3.8 (12.5)[56] |

Vertebrates

Mammals (Mammalia)

The blue whale is the largest mammal of all time, with the largest known specimen being 33.6 m (110.2 ft) long and the largest weighted specimen being 190 tonnes.[12][57][58] The extinct whale species Perucetus colossus was shorter than the blue whale, at 17.0–20.1 meters (55.8–65.9 ft) but it is estimated to have rivaled or surpassed it in weight, at 85–340 tonnes. At the highest estimates, this would make Perucetus the heaviest known animal in history.[8]

The largest land mammal extant today is the African bush elephant. The largest extinct land mammal known was long considered to be Paraceratherium orgosensis, a rhinoceros relative thought to have stood up to 4.8 m (15.7 ft) tall, measured over 7.4 m (24.3 ft) long and may have weighed about 17 tonnes.[59][60] In 2015, a study suggested that one example of the proboscidean Palaeoloxodon namadicus may have been the largest land mammal ever, based on extensive research of fragmentary leg bone fossils from one individual, with a maximum estimated size of 22 tonnes.[61][59]

Stem-mammals (Synapsida)

The

- Caseasaurs (Caseasauria)

- The herbivorous Alierasaurus was the largest caseid and the largest amniote to have lived at the time, with an estimated length around 6–7 m (20–23 ft).[65] Another huge caseasaur is Cotylorhynchus hancocki, with an estimated length and weight of at least 6 m (20 ft)[66] and more than 500 kg (1,100 lb).[67]

- Sphenacodontids (Sphenacodontidae)

- The biggest carnivorous synapsid of Early Permian was Dimetrodon, which could reach 4.6 m (15 ft) and 250 kg (550 lb).[68] The largest members of the genus Dimetrodon were also the world's first fully terrestrial apex predators.[69]

- Tappenosaurids (Tappenosauridae)

- The Middle Permian Tappenosaurus was estimated at 5.5 m (18 ft) in length which is comparable in size with the largest dinocephalians.[70]

- Therapsids (Therapsida)

- The plant-eating dicynodont Lisowicia bojani is the largest-known of all non-mammalian synapsids, at 4.5 m (15 ft) and 9,000 kg (20,000 lb).[62][71][72] The largest carnivorous therapsid was the aforementioned Anteosaurus from what is now South Africa during Middle Permian epoch. It reached 5–6 m (16–20 ft) long, and about 500–600 kg (1,100–1,300 lb) in weight.[64]

Reptiles (Reptilia)

The largest living reptile, a representative of the order Crocodilia, is the saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) of Southern Asia and Australia, with adult males being typically 3.9–5.5 m (13–18 ft) long. The largest confirmed saltwater crocodile on record was 6.32 m (20.7 ft) long, and weighed about 1,360 kg (3,000 lb).[1] Unconfirmed reports of much larger crocodiles exist, but examinations of incomplete remains have never suggested a length greater than 7 m (23 ft).[73] Also, a living specimen estimated at 7 m (23 ft) and 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) has been accepted by the Guinness Book of World Records.[74] However, due to the difficulty of trapping and measuring a very large living crocodile, the accuracy of these dimensions has yet to be verified. A specimen named Lolong caught alive in the Philippines in 2011 (died February 2013) was found to have measured 6.17 m (20.2 ft) in length.[75][76][77][78][79]

The Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis), also known as the "Komodo monitor", is a large species of lizard found in the Indonesian islands of Komodo, Rinca, Flores, Gili Motang, Nusa kode and Padar. A member of the monitor lizard family (Varanidae), it is the largest living species of lizard, growing to a maximum length of more than 3 metres (9.8 feet) in rare cases and weighing up to approximately 166 kilograms (366 pounds).[80]

Largest living reptiles

The following is a list of the largest living reptile species ranked by average weight, which is dominated by the crocodilians. Unlike mammals, birds, or fish, the mass of large reptiles is frequently poorly documented and many are subject to conjecture and estimation.[1]

| Rank | Animal | Average mass [kg (lb)] |

Maximum mass [kg (lb)] |

Average total length [m (ft)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saltwater crocodile | 450 (1,000)[81][82] | 2,000 (4,400)[83][84] | 4.5 (14.8)[81][85] |

| 2 | Nile crocodile | 410 (900)[86] | 1,090 (2,400)[1] | 4.2 (13.8)[86] |

| 3 | Orinoco crocodile | 380 (840)[citation needed] | 1,100 (2,400)[citation needed] | 4.1 (13.5)[87][88] |

| 4 | Leatherback sea turtle | 364 (800)[89][90] | 932 (2,050)[1] | 2.0 (6.6)[1] |

| 5 | American crocodile | 336 (740)[91] | 1,000 (2,200)[92] | 4.0 (13.1)[93][94] |

| 6 | Black caiman | 300 (661)[citation needed] | 1,000 (2,200)[citation needed] | 3.9 (12.8)[95][96][97][98] |

| 7 | Gharial | 250 (550)[99] | 1,000 (2,200)[100] | 4.5 (14.8)[99] |

| 8 | American alligator | 240 (530)[101][102] | 1,000 (2,200)[1] | 3.4 (11.2)[102] |

| 9 | Mugger crocodile | 225 (495)[101] | 700 (1,500)[103] | 3.3 (10.8)[102] |

| 10 | False gharial | 210 (460)[104] | 590 (1,300)[105] | 4.0 (13.1)[106] |

| 11 | Aldabra giant tortoise | 205 (450)[107] | 360 (790)[1] | 1.4 (4.6)[108] |

| 12 | Loggerhead sea turtle | 200 (441)[citation needed] | 545 (1,202)[citation needed] | 0.95 (3.2)[108] |

| 13 | Green sea turtle | 190 (418.9)[109] | 395 (870.8)[86] | 1.12 (3.67)[86] |

| 14 | Slender-snouted crocodile |

180 (400)[110] | 325 (720)[110] | 3.3 (10.8)[110] |

| 15 | Galapagos tortoise | 175 (390)[111] | 417 (919)[112] | 1.5 (4.9)[113] |

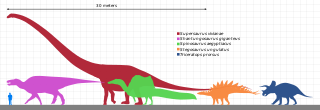

Dinosaurs (Dinosauria)

Dinosaurs are now extinct, except for birds, which are theropods.

- Sauropods (Sauropoda)

- The largest dinosaurs, and the largest animals to ever live on land, were the plant-eating, long-necked Carnegie Natural History Museum in 1907. A Patagotitan specimen found in Argentina in 2014 is estimated to have been 37–40 m (121–131 ft) long and 20 m (66 ft) tall, with a weight of 69–77 tonnes.[120][121]

- There were larger sauropods, but they are known only from a few bones. The current record-holders include Argentinosaurus, which may have weighed 100 tonnes; Supersaurus which might have reached 34 m (112 ft) in length and Sauroposeidon which might have been 18 m (59 ft) tall. Some abnormal specimens such as specimen BYU 9024 of the Barosaurus genus could reach an astounding 45-48 meters long, with mass varying from the 'modest' 60-66 tons to the more immense 92-120 tons.[122][123][124] Two other such sauropods include Bruhathkayosaurus and Maraapunisaurus. Both are known only from fragments that no longer exist. Bruhathkayosaurus might have been between 40–44 m (131–144 ft) in length and 175–220 tonnes in weight according to some estimates, with recent estimates being place between 110-170 tons.[125][10] Maraapunisaurus might have been approximately 35–40 m long and 80–120 tonnes or more.[126] Each of these two 'super-sauropods' would have easily rivalled the largest blue whale in size.[10][12]

| Rank | Animal | Average mass [tonnes] |

Maximum mass [tonnes] |

Average total length [m (ft)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bruhathkayosaurus matleyi |

110-170[10] | 240[10] | 44.1 (144.6)[127][128] |

| 2 | Maraapunisaurus fragillimus |

80-120[129] | 150[130] | 35-40 (115-131)[129] |

| 3 | Barosaurus lentus BYU 9024 |

60-66[122][123][131][132] | 92-120[124] | 45-48 (148-157)[132] |

| 4 | Argentinosaurus huinculensis |

75-80[117] | 100[117][133] | 35–39.7 (115–130)[117][134] |

| 5 | Mamenchisaurus | 50-80[135] | 80[135] | 26–35 (85–115)[135] |

| 6 | Notocolossus gonzalezparejasi |

44.9–75.9[133] | 75.9[133] | 28 (92)[133] |

| 7 | Patagotitan mayorum |

55-69[136] | 77[136] | 33–37 (108–121)[136] |

| 8 | Puertasaurus reuili |

50-60[137] | 60 | 27-30 (89-98)[138][139][140] |

| 9 | Sauroposeidon proteles |

40-60[141] | 60[141] | 27–34 (89–112)[141][137][142] |

| 10 | Dreadnoughtus schrani |

22.1–59.3[143] | 59.3[143] | 26 (85)[133][143] |

- Theropods (Theropoda)

- The largest have been lower.

- Another giant theropod is Spinosaurus aegyptiacus from the mid-Cretaceous of North Africa. Size estimates have been fluctuating far more over the years, with length estimates ranging from 12.6 to 18 m and mass estimates from 7 to 20.9 t.[146][147] Recent findings favor a length exceeding 15 m [148] and a body mass of 7.5 tons.[149]

- Other contenders known from partial skeletons include Giganotosaurus carolinii (est. 12.2–13.2 m and 6-13.8 tonnes) and Carcharodontosaurus saharicus (est. 12-13.3 m and 6.2-15.1 tonnes).[147][150][151][152][153][122]

- The largest extant theropod is the common ostrich(see birds, below).

- Armored dinosaurs (Thyreophora)

- The largest thyreophorans were Ankylosaurus and Stegosaurus, from the Late Cretaceous and Late Jurassic periods (respectively) of what is now North America, both measuring up to 9 m (30 ft) in length and estimated to weigh up to 6 tonnes.[154][155]

- Ornithopods (Ornithopoda)

- The largest ornithopods were the hadrosaurids Shantungosaurus, a late Cretaceous dinosaur found in the Shandong Peninsula of China, and Magnapaulia from the late Cretaceous of North America. Both species are known from fragmentary remains but are estimated to have reached over 15 m (49 ft) in length[156][157] and were likely the heaviest non-sauropod dinosaurs, estimated at over 23 tonnes.[157]

- Ceratopsians (Ceratopsia)

- The largest ceratopsians were Triceratops and its ancestor Eotriceratops from the late Cretaceous of North America. Both estimated to have reached about 9 m (30 ft) in length[158] and weighed 12 tonnes.[159][160]

Birds (Aves)

The largest living bird, a member of the Struthioniformes, is the common ostrich (Struthio camelus), from the plains of Africa. A large male ostrich can reach a height of 2.8 m (9.2 ft) and weigh over 156 kg (344 lb).[161] A mass of 200 kg (440 lb) has been cited for the common ostrich but no wild ostriches of this weight have been verified.[162] Eggs laid by the ostrich can weigh 1.4 kg (3.1 lb) and are the largest eggs in the world today.[citation needed]

The largest bird in the fossil record may be the extinct

The heaviest bird ever capable of flight was

Heaviest living bird species

The following is a list of the heaviest living bird species based on maximum reported or reliable mass, but average weight is also given for comparison. These species are almost all flightless, which allows for these particular birds to have denser bones and heavier bodies. Flightless birds comprise less than 2% of all living bird species.[citation needed]

| Rank | Animal | Binomial Name | Average mass [kg (lb)] |

Maximum mass [kg (lb)] |

Average total length [cm (ft)] |

Flighted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Common ostrich |

Struthio camelus | 104 (230)[169] | 156.8 (346)[169] | 210 (6.9)[170] | No |

| 2 | Somali ostrich | Struthio molybdophanes | 90 (200)[169] | 130 (287)[citation needed] | 200 (6.6)[169] | No |

| 3 | Southern cassowary | Casuarius casuarius | 45 (99)[169] | 85 (190)[171] | 155 (5.1)[169] | No |

| 4 | Northern cassowary | Casuarius unappendiculatus | 44 (97)[169] | 75 (170)[169] | 149 (4.9)[170] | No |

| 5 | Emu | Dromaius novaehollandiae | 33 (73)[169][172] | 70 (150)[citation needed] | 153 (5)[169] | No |

| 6 | Emperor penguin | Aptenodytes forsteri | 31.5 (69)[170][173] | 46 (100)[170] | 114 (3.7)[170] | No |

| 7 | Greater rhea | Rhea americana | 23 (51)[172] | 40 (88)[170] | 134 (4.4)[169] | No |

| 8 | Domestic turkey/wild turkey | Meleagris gallopavo | 13.5 (29.8) [174] | 39 (86)[175] | 100 - 124.9 (3.3 – 4.1)[citation needed] | Yes |

| 9 | Dwarf cassowary | Casuarius bennetti | 19.7 (43)[169] | 34 (75)[169] | 105 (3.4)[citation needed] | No |

| 10 | Lesser rhea |

Rhea pennata | 19.6 (43)[169] | 28.6 (63)[169] | 96 (3.2)[170] | No |

| 11 | Mute swan | Cygnus olor | 11.87 (26.2) | 23 (51) | 100-130 (3.3 - 4.3)[176] | Yes |

| 12 | Great bustard | Otis tarda | 10.6 (23.4)[citation needed] | 21 (46)[1] | 115 (3.8)[citation needed] | Yes |

| 13 | King penguin | Aptenodytes patagonicus | 13.6 (30)[170][173] | 20 (44)[177] | 92 (3)[citation needed] | No |

| 14 | Kori bustard | Ardeotis kori | 11.4 (25.1)[170] | 20 (44.1)[citation needed] | 150 (5)[170] | Yes |

| 15 | Trumpeter swan | Cygnus buccinator | 11.6 (25.1) | 17.2 (38) | 138 - 165 (4.5 - 5.4) | Yes |

| 16 | Wandering albatross |

Diomedea exulans | 11.9 (24) | 16.1 (38)[178] | 107 - 135 (3.5 - 4.4) | Yes |

| 17 | Whooper swan | Cygnus cygnus | 11.4 (25) | 15.5 (32) | 140 - 165 (4.5 - 5.4) | Yes |

| 18 | Dalmatian Pelican |

Pelecanus crispus | 11.5 (25) | 15 (33.1)[citation needed] | 183 (6)[citation needed] | Yes |

| 19 | Andean condor | Vultur gryphus | 11.3 (25)[176] | 14.9 (33)[176] | 100 - 130 (3.3 - 4.3)[176] | Yes |

Amphibians (Amphibia)

The largest living

- Frogs (Anura)

- The largest member of the largest order of dendrobatid is the Colombian golden poison frog (Phyllobates terribilis), which can attain a length of 6 cm (2.4 in) and nearly 28.3 g (1.00 oz).[185] Most frogs are classified under the suborder Neobatrachia, although nearly 200 species are part of the suborder Mesobatrachia, or ancient frogs. The largest of these are the little-known Brachytarsophrys or Karin Hills frogs, of South Asia, which can grow to a maximum snout-to-vent length of 17 cm (6.7 in) and a maximum weight of 0.54 kg (1.2 lb).[186]

- Caecilians (Gymnophiona)

- The largest of the worm-like caecilians is the Colombian Thompson's caecilian (Caecilia thompsoni), which reaches a length of 1.5 m (4.9 ft), a width of about 4.6 cm (1.8 in) and can weigh up to about 1 kg (2.2 lb).[1]

- Salamanders (Urodela)

- Besides the previously mentioned Chinese and South China giant salamanders, the closely related reticulated siren of the southeastern United States rivals the hellbender in size, although it is more lean in build.[187] The largest of the newts is the Iberian ribbed newt (Pleurodeles waltl), which can grow up to 30 cm (12 in) in length.[188]

Fish

Invertebrate chordates

Tunicates (Tunicata)

The largest tunicate is Synoicum pulmonaria, found at depths of 20 and 40 metres (66 and 131 ft), and are up to 14 centimetres (6 in) in diameter. It is also present in the northwestern Atlantic Ocean, around the coasts of Greenland and Newfoundland, but is less common here than in the east, and occurs only at depths between 10 and 13 metres (33 and 43 ft).[189]

- Entergonas (Enterogona)

- The largest entergona is Synoicum pulmonaria it is usually found at depths between about 20 and 40 metres (66 and 131 ft) and can grow to over a metre (yard) in length. It is also present in the northwestern Atlantic Ocean, around the coasts of Greenland and Newfoundland, but is less common here than in the east, and occurs only at depths between 10 and 13 metres (33 and 43 ft).[189]

- Pleurogonas (Pleurogona)

- The largest pleurogona is Pyura pachydermatina .[190] In colour it is off-white or a garish shade of reddish-purple. The stalk is two thirds to three quarters the length of the whole animal which helps distinguish it from certain invasive tunicates not native to New Zealand such as Styela clava and Pyura stolonifera.[191] It is one of the largest species of tunicates and can grow to over a metre (yard) in length.[192]

- Aspiraculates (Aspiraculata)

- The largest aspiraculate is Oligotrema large and surrounded by six large lobes; the cloacal syphon is small. They live exclusively in deep water and range in size from less than one inch (2 cm) to 2.4 inches (6 cm).

Thaliacea

The largest thaliacean, Pyrosoma atlanticum, is cylindrical and can grow up to 60 cm (2 ft) long and 4–6 cm wide. The constituent zooids form a rigid tube, which may be pale pink, yellowish, or bluish. One end of the tube is narrower and is closed, while the other is open and has a strong diaphragm. The outer surface or test is gelatinised and dimpled with backward-pointing, blunt processes. The individual zooids are up to 8.5 mm (0.33 in) long and have a broad, rounded branchial sac with gill slits. Along the side of the branchial sac runs the endostyle, which produces mucus filters. Water is moved through the gill slits into the centre of the cylinder by cilia pulsating rhythmically. Plankton and other food particles are caught in mucus filters in the processes as the colony is propelled through the water. P. atlanticum is bioluminescent and can generate a brilliant blue-green light when stimulated.[193][194]

- Doliolida (Doliolida)

- The largest doliolida is Doliolida [195] The doliolid body is small, typically 1–2 cm long, and barrel-shaped; it features two wide siphons, one at the front and the other at the back end, and eight or nine circular muscle strands reminiscent of barrel bands. Like all tunicates, they are filter feeders. They are free-floating; the same forced flow of water through their bodies with which they gather plankton is used for propulsion - not unlike a tiny ramjet engine. Doliolids are capable of quick movement. They have a complicated lifecycle consisting of sexual and asexual generations. They are nearly exclusively tropical animals, although a few species are found as far north as northern California.[citation needed]

- Salps (Salpida)

- The largest salp is Cyclosalpa bakeri 15cm (6ins) long. There are openings at the anterior and posterior ends of the cylinder which can be opened or closed as needed. The bodies have seven transverse bands of muscle interspersed by white, translucent patches. A stolon grows from near the endostyle (an elongated glandular structure producing mucus for trapping food particles). The stolon is a ribbon-like organ on which a batch of aggregate forms of the animal are produced by budding. The aggregate is the second, colonial form of the salp and is also gelatinous, transparent and flabby. It takes the shape of a radial whorl of individuals up to about 20cm (4in) in diameter. It is formed of approximately 12 zooids linked side by side in a shape that resembles a crown.[193][196] are largest thetyses: Thetys vagina Individuals can reach up to 30 cm (12 in) long.[citation needed]

- Larvaceans (Larvacea)

- The largest larvacean is Appendicularia 1 cm (0.39 in) in body length (excluding the tail).[citation needed]

Cephalochordates (Leptocardii)

The largest lancelet is the European lancelet (Branchiostoma lanceolatum) "primitive fish". It can grow up to 6 cm (2.5 in) long.[197]

Invertebrate non-chordates

Echinoderms (Echinodermata)

The largest species of

- Crinoids (Crinoidea)

- The largest species of crinoids grew much larger, and stalk lengths up to 40 m (130 ft) have been found in the fossil record.[199]

- Sea urchins and allies (Echinoidea)

- The largest sea urchin is the species Sperosoma giganteum from the deep northwest Pacific Ocean, which can reach a shell width of about 30 cm (12 in).[200] Another deep sea species Hygrosoma hoplacantha is only slightly smaller.[200] The largest species found along the North America coast is the Pacific red sea urchin (Mesocentrotus franciscanus) where the shell can reach 19 cm (7.5 in).[201] If the spines enter into count, the biggest species may be a Diadematidae like Diadema setosum, with a test up to 10 cm (3.9 in) only, but its spines can reach up to 30 cm (12 in) in length.[202]

- Sea cucumbers (Holothuroidea)

- The bulkiest species of sea cucumber are Stichopus variegatus and Thelenota anax, weighing several pounds, being about 21 cm (8.3 in) in diameter, and reaching a length of 1 m (3.3 ft) when fully extended. Synapta maculata can reach an extended length of 3 m (9.8 ft), but is extremely slender (3-5cm) and weigh much less than Stichopodids.[1]

- Brittle stars (Ophiuroidea)

- The largest known specimen of euryalids, the biggest ophiurid brittle star may be Ophiopsammus maculata (6–7 inches).[203]

- Sea stars (Asteroidea)

- The heaviest sea star is Thromidia gigas from the Indo-Pacific, which can surpass 6 kg (13 lb) in weight, but only has a diameter of about 65 cm (2.13 ft).[198][200] Despite its relatively small disk and weight, the long slender arms of Midgardia xandaros from the Gulf of California makes it the sea star with the largest diameter at about 1.4 m (4.5 ft).[200] Mithrodia clavigera may also become wider than 1 m (39 in) in some cases, with stout arms.[citation needed]

Flatworms (Platyhelminthes)

- Monogenean flatworms (Monogenea)

- The largest known members of this group of very small parasites are among the genus of Listrocephalos, reaching a length of 2 cm (0.79 in).[204]

- Flukes (Trematoda)

- The largest known species of

- Tapeworms (Cestoda)

- The largest known species of

Segmented worms (Annelida)

The largest of the

Ribbon worms (Nemertea)

The largest

Mollusks (Mollusca)

Both the largest mollusks and the largest of all invertebrates (in terms of mass) are the largest squids. The colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni) is projected to be the largest invertebrate.[210] Current estimates put its maximum size at 12 to 14 m (39 to 46 ft) long and 750 kg (1,650 lb),[211] based on analysis of smaller specimens. In 2007, authorities in New Zealand announced the capture of the largest known colossal squid specimen. It was initially thought to be 10 m (33 ft) and 450 kg (990 lb). It was later measured at 4.2 m (14 ft) long and 495 kg (1,091 lb) in weight. The mantle was 2.5 m (8.2 ft) long when measured.[212][213]

The giant squid (Architeuthis dux) was previously thought to be the largest squid, and while it is less massive and has a smaller mantle than the colossal squid, it may exceed the colossal squid in overall length including tentacles. One giant squid specimen that washed ashore in 1878 in Newfoundland reportedly measured 16.8 m (55 ft) in total length (from the tip of the mantle to the end of the long tentacles), head and body length 6.1 m (20 ft), 4.6 m (15 ft) in circumference at the thickest part of mantle, and weighed about 900 kg (2,000 lb). This specimen is still often cited as the largest invertebrate that has ever been examined.[1][214][215] However, no animals approaching this size have been scientifically documented and, according to giant squid expert Steve O'Shea, such lengths were likely achieved by greatly stretching the two tentacles like elastic bands.[216]

- Aplacophorans (Aplacophora)

- The largest known of these worm-like, shell-less

- Chitons (Polyplacophora)

- The largest of the chitons is the gumboot chiton, Cryptochiton stelleri, which can reach a length of 33 cm (13 in) and weigh over 2 kg (4.4 lb).[218]

- Bivalves (Bivalvia)

- The largest of the Platyceramus platinus, a Cretaceous giant that reached an axial length of up to 3 m (nearly 10 ft).[219]

- Gastropods (Gastropoda)

- The "largest" of this most diverse and successful can be defined in various ways.

- The living gastropod species that has the largest (longest) shell is Syrinx aruanus with a maximum shell length of 0.91 m (3.0 ft), a weight of 18 kg (40 lb) and a width of 96 cm (38 in).[220][221] Another giant species is Melo amphora, which in a 1974 specimen from Western Australia, measured 0.71 m (2.3 ft) long, had a maximum girth of 0.97 m (3.2 ft) and weighed 16 kg (35 lb).[1]

- The largest shell-less gastropod is the giant black sea hare (Aplysia vaccaria) at 0.99 m (3.2 ft) in length and almost 14 kg (31 lb) in weight.

- The largest of the land snails is the giant African snail (Achatina achatina) at up to 1 kg (2.2 lb) and 35 cm (14 in) long.

- Cephalopods (Cephalopoda)

- (See giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini), can grow to be very large. The largest confirmed weight of a giant octopus is 74 kg (163 lb),[222] with a 7 m (23 ft) arm span (with the tentacles fully extended) and a head-to-tentacle-tip length of 3.9 m (13 ft).[223] Specimens have been reported up to 125 kg (276 lb) but are unverified. A weight of 10 - 50kg is a much more common size.[1]

Roundworms (Nematoda)

The largest

Velvet worms (Onychophora)

The largest

Arthropods (Arthropoda)

The largest arthropod known to have existed is the eurypterid (sea scorpion) Jaekelopterus, reaching up to 2.5 m (8.2 ft) in body length, followed by the millipede relative Arthropleura at around 2.1 m (6.9 ft) in length.[227] Among living arthropods, the Japanese spider crab (Macrocheira kaempferi) is the largest in overall size, the record specimen, caught in 1921, had an extended arm span of 3.8 m (12 ft) and weighed about 19 kg (42 lb).[1] The heaviest is the American lobster (Homarus americanus), the largest verified specimen, caught in 1977 off of Nova Scotia weighed 20 kg (44 lb) and its body length was 1.1 m (3.6 ft).[1] The largest land arthropod and the largest land invertebrate is the coconut crab (Birgus latro), up to 40 cm (1.3 ft) long and weighing up to 4 kg (8.8 lb) on average. Its legs may span 1 m (3.3 ft).[1]

Arachnids (Arachnida)

Both spiders and scorpions include contenders for the largest arachnids.

- Spiders (Araneae)

- The largest species of arachnid by length is probably the Brazilian salmon pink (Lasiodora parahybana). The huntsman spider may span up to 29 cm (11 in) across the legs, while in the New World tarantulas like Theraphosa can range up to 26 cm (10 in).[1] In Grammostola, Theraphosa and Lasiodora, the weight is projected to be up to at least 150 g (5.3 oz) and body length is up to 10 cm (3.9 in).[229]

- Scorpions (Scorpiones)

- The largest of the Pulmonoscorpius kirktonensis, a giant extinct species of scorpion from Scotland, at an estimated length of 0.7 m (2.3 ft),[230] and the aquatic Brontoscorpio, at up to 94 cm (3.08 ft) which is only known from a free finger.[231]

- Pseudoscorpions (Pseudoscorpiones)

- The largest pseudoscorpion is Garypus titanius, from Ascension island, which can be 12 mm (0.47 in) long.[232]

Crustaceans (Crustacea)

The largest crustacean is the

- Branchiopods (Branchiopoda)

- The largest of these primarily freshwater crustaceans is probably Branchinecta gigas, which can reach a length 10 cm (3.9 in).[238]

- Barnacles and allies (Maxillopoda)

- The largest species is giant acorn barnacle, Balanus nubilis, reaching 7 cm (2.8 in) in diameter and 12.7 cm (5.0 in) high.[240]

- Ostracods (Ostracoda)

- The largest living representative of these small and little-known but numerous crustaceans is the species Gigantocypris australis females of which reaching a maximum length of 3 cm (1.2 in).

- Amphipods, isopods, and allies (Peracarida)

Giant isopod - The largest species is the giant isopod (Bathynomus pergiganteus), which can reach a length of 45 cm (18 inches) and a weight of 1.7 kg (3.7 lb).[241]

- Remipedes (Remipedia)

- The largest of these cave-dwelling crustaceans is the species Godzillius robustus, at up to 4.5 cm (1.8 in).[242]

Horseshoe crabs (Xiphosura)

The four modern horseshoe crabs are of roughly the same sizes, with females measuring up to 60 cm (2.0 ft) in length and 5 kg (11 lb) in weight.[243]

Sea spiders (Pycnogonida)

The largest of the sea spiders is the deep-sea species Colossendeis colossea, attaining a leg span of nearly 60 cm (2.0 ft).[244]

Trilobites (Trilobita)

Some of these extinct marine arthropods exceeded 60 cm (24 in) in length. A nearly complete specimen of Isotelus rex from Manitoba attained a length over 70 cm (28 in), and an Ogyginus forteyi from Portugal was almost as long. Fragments of trilobites suggest even larger record sizes. An isolated pygidium of Hungioides bohemicus implies that the full animal was 90 cm (35 in) long.[245][246]

Myriapods (Myriapoda)

- Centipedes (Chilopoda)

- The biggest of the centipedes is Scolopendra gigantea of the neotropics, reaching a length of 33 cm (13 in).[247]

- Millipedes (Diplopoda)

- Two species of millipede both reach a very large size: Archispirostreptus gigas of East Africa and Scaphistostreptus seychellarum, endemic to the Seychelles islands. Both of these species can slightly exceed a length of 28 cm (11 in) and measure over 2 cm (0.79 in) in diameter.[1] The largest ever known was the Arthropleura, a gigantic prehistoric specimen that reached nearly 189 cm (74 in).

- Symphylans (Symphyla)

- The largest known symphylan is Hanseniella magna, originating in Tasmanian caves, which can reach lengths from 25 mm (0.98 in) up to 30 mm (1.2 in).[248]

Insects (Insecta)

Some moths and butterflies have much larger areas than the heaviest beetles, but weigh a fraction as much.

The longest insects are the stick insects, see below.

Representatives of the extinct dragonfly-like

- Cockroaches and termites (Blattodea)

- The largest Isoptera), have recently been re-considered to belong in Blattodea. The largest of the termites is the African species Macrotermes bellicosus. The queen of this species can attain a length of 14 cm (5.5 in) and breadth of 5.5 cm (2.2 in) across the abdomen; other adults, on the other hand, are about a third of the size.[1]

- Beetles (Coleoptera)

- The beetles are the largest order of organisms on earth, with about 400,000 species so far identified. The most massive species are the Goliathus, Megasoma and Titanus beetles already mentioned. Another fairly large species is the Hercules beetle (Dynastes hercules) of the neotropic rainforest with a maximum overall length of at least 19 cm (7.5 in) including the extremely long pronotal horn. The weight in this species does not exceed 16.5 g (0.58 oz).[1] The longest overall beetle is a species of longhorn beetle, Batocera wallacei, from New Guinea, which can attain a length of 26.6 cm (10.5 in), about 19 cm (7.5 in) of which is comprised by the long antennae.[1]

- Earwigs (Dermaptera)

- Since 1798, the largest of the earwigs has been the Saint Helena giant earwig (Labidura herculeana), endemic to the island of its name, measuring up to 8 cm (3.1 in) in length.[251] As of 2014, with the declaring of the organism extinct by the IUCN,[252] this may no longer be the case, although some believe a small number individuals are still extant.[253]

- True flies (Diptera)

- The largest species of this order, which includes the common housefly, is the neotropical species Gauromydas heros, which can reach a length of 6 cm (2+3⁄8 in) and a wingspan of 10 cm (3.9 in).[1] Species of crane fly, the largest of which is Holorusia brobdignagius, can attain a length of 23 cm (9.1 in) but are extremely slender and much lighter in weight than Gauromydas.

- Mayflies (Ephemeroptera)

- The largest mayflies are members of the genus Proboscidoplocia from Madagascar. These insects can reach a length of 7 cm (2.8 in).[254]

- True bugs (Hemiptera)

- The largest species of this diverse order is usually listed as the Tacua can also grow to comparably large sizes. The largest type of aphid is the giant oak aphid (Stomaphis quercus), which can reach an overall length of 2 cm (0.79 in).[260] The biggest species of leafhopper is Ledromorpha planirostris, which can reach a length of 2.8 cm (1.1 in).[261], the largest bee.

Megachile pluto - Ants and allies (Hymenoptera)

- The largest of the ants, and the heaviest species of the order, are the females of the African Dorylus helvolus, reaching a length of 5.1 cm (2.0 in) and a weight of 8.5 g (0.30 oz).[1] The ant that averages the largest for the mean size within the whole colony is a ponerine ant, Dinoponera gigantea, from South America, averaging up to 3.3 cm (1.3 in) from the mandibles to the end of abdomen.[1] Workers of the bulldog ant (Myrmecia brevinoda) of Australia are up to 3.7 cm (1.5 in) in total length, although much of this is from their extremely large mandibles.[1] The largest of the bee species, also in the order Hymenoptera, is Megachile pluto of Indonesia, the females of which can be 3.8 cm (1.5 in) long, with a 6.3 cm (2.5 in) wingspan. Nearly as large, the carpenter bees can range up to 2.53 cm (1.00 in).[1] The largest wasp is probably the so-called tarantula hawk species Pepsis pulszkyi of South America, at up to 6.8 cm (2.7 in) long and 11.6 cm (4.6 in) wingspan, although many other Pepsis approach a similar size. The giant scarab-hunting wasp Megascolia procer may rival the largest tarantula hawks in weight and wingspan, though its body is not as long.[1]

- Moths and allies (Lepidoptera)

Queen Alexandra's birdwing. - The Xyleutes boisduvali) of Australia, which has weighed up to 20 g (0.71 oz) although the species does not surpass 25.5 cm (10.0 in) in wingspan.[1]

- Mantises (Mantodea)

- The largest species of this order is Toxodera denticulata from Java, which has been measured up to 20 cm (7.9 in) in overall length.[264] However, an undescribed species from the Cameroon jungle is allegedly much larger than any other mantis and may rival the larger stick insects for the longest living insect.[265] Among widespread mantis species, the largest is the Chinese mantis (Tenodera aridifolia). The females of this species can attain a length of up to 10.6 cm (4.2 in).

- Scorpionflies (Mecoptera)

- The largest scorpionfly, the common scorpionfly (Panorpa communis), can reach a body length of about 30 millimetres (1.2 in).[266]

- Alderflies and allies (Megaloptera)

- This relatively small insect order includes some rather large species, many of which are noticeable for their elongated, imposing mandibles. The dobsonflies reach the greatest sizes of the order and can range up to 12.5 cm (4.9 in) in length.[267]

- Net-winged insects (Neuroptera)

- These flying insects reach their largest size in sedimentary rocks, Makarkinia adamsi had wings nearly 140–160 mm (5.5–6.3 in) in length.[271]

- Dragonflies and damselflies (Odonata)

- The largest species of Odonata is the Megaloprepus (at up to 7 g (0.25 oz)), it is smaller in its linear dimensions.[1]

- Grasshoppers and allies (Orthoptera)

- The largest of this widespread, varied complex of insects are the Macrolyristes corporalis of Southeast Asia which can range up to 21.5 cm (8.5 in) with its long legs extended and can have a wingspan of 20 cm (7.9 in).[274]

- Stick insects (Phasmatodea)

- The longest known Heteropteryx dilatata) of Malaysia does not reach the extreme lengths of its cousins, the body reaching up to 16 cm (6.3 in) long, but it is much bulkier. The largest Heteropteryx weighed about 65 g (2.3 oz) and was 3.5 cm (1.4 in) wide across the thickest part of the body.[1]

- Lice (Phthiraptera)

- These insects, which live parasitically on other animals, are as a rule quite small. The largest known species is the hog louse, Haematopinus suis, a sucking louse that lives on large livestock like pigs and cattle. It can range up to 6 mm (0.24 in) in length.[282]

- Stoneflies (Plecoptera)

Pteronarcys californica - The largest species of stonefly is Pteronarcys californica of western North America, a species favored by fishermen as lures. This species can attain a length of 5 cm (2.0 in) and a wingspan of over 9.5 cm (3.7 in).[283]

- Booklice (Psocoptera)

- The largest of this order of very small insects are the barklice of the genus Psocus, the top size of which is about 1 cm.[284]

- Fleas (Siphonaptera)

- The largest species of flea is Hystrichopsylla schefferi. This parasite is known exclusively from the fur of the mountain beaver (Aplodontia rufa) and can reach a length of 1.2 cm (0.47 in).[1]

- Silverfishes and allies (Thysanura)

- These ancient flightless insects, some of which feed on human household objects, can range up to 4.3 cm (1.7 in) in length. A 350 million year old form was known to grow quite large, at up to 6 cm (2.4 in).[citation needed]

- Thrips (Thysanoptera)

- Members of the genus thrips. The maximum size these species attain is approximately 1.3 cm (0.51 in) in length.[285]

- Caddisflies (Trichoptera)

- The largest of the small, moth-like caddisflies is Eubasilissa maclachlani. This species can range up to 7 cm (2.8 in) across the wings.[286]

- Angel insects (Zoraptera)

- The largest angel insect species,

Cnidarians (Cnidaria)

The lion's mane jellyfish (Cyanea capillata) is the largest cnidarian species, of the class Scyphozoa. The largest known specimen of this giant, found washed up on the shore of Massachusetts Bay in 1870,[289][290] had a bell diameter of 2.5 m (8.2 ft), a weight of 150 kg (330 lb). The tentacles of this specimens were as long as 37 m (121 ft) and were projected to have a tentacular spread of about 75 m (246 ft) making it one of the longest extant animals.[1]

- Corals and sea anemones (Anthozoa)

- The largest individual species are the can be over 10 m (33 ft), but the actual individual organisms are quite small.

- Hydrozoans (Hydrozoa)

- The colonial siphonophore Praya dubia can attain lengths of 40–50 m (130–160 ft).[293] The Portuguese man o' war's (Physalia physalis) tentacles can attain a length of up to 50 m (160 ft).[294] On 6 April 2020 the Schmidt Ocean Institute announced the discovery of a giant Apolemia siphonophore in submarine canyons near Ningaloo Coast, measuring 15 m (49 ft) diameter with a ring approximately 47 m (154 ft) long, claiming it was possibly the largest siphonophore ever recorded.[295][296]

Sponges (Porifera)

The largest known species of

- Calcareous sponges (Calcarea)

- The largest known of these small, inconspicuous sponges is probably the species Pericharax heteroraphis, attaining a height of 30 cm (0.98 ft). Most calcareous sponges do not exceed 10 cm (3.9 in) tall.[citation needed]

- Hexactinellid sponges (Hexactinellida)

- A relatively common species, Rhabdocalyptus dawsoni, can reach a height of 1 m (3.3 ft) once they are of a very old age.[299] This is the maximum size recorded for a hexactinellid sponge.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9

- ^ Davies, Ella (20 April 2016). "The longest animal alive may be one you never thought of". BBC Earth. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ "Largest mammal". Guinness World Records.

- PMID 38436015.

- ^ "How Large Are Blue Whales Really? Size Comparison". Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2019 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ "How big are blue whales? And what does 'big' mean? By palaeozoologist on DeviantArt". February 2014.

- PMID 25649000.

- ^ S2CID 260433513. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ Pester, Patrick (8 March 2024). "Colossus the enormous 'oddball' whale is not the biggest animal to ever live, scientists say". Lve Science. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ S2CID 259782734.

- ISBN 978-0-470-34448-4.

- ^ a b c Zimmer, Carl (29 February 2024). "Researchers Dispute Claim That Ancient Whale Was Heaviest Animal Ever - A new study argues that Perucetus, an ancient whale species, was certainly big, but not as big as today's blue whales". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 February 2024. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Mark Tandy. Lives of Whales Archived 16 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Iwcoffice.org

- ^ Blue Whale. The Marine Mammal Center

- ^ North Pacific Right Whale | Marine education | Alaska Sea Grant. Seagrant.uaf.edu (15 February 2008)

- ^ ISBN 978-0-375-41141-0

- ^ Bowhead Whales, Balaena mysticetus. Marinebio.org (30 September 2011)

- ^ Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife – Maine Endangered Species Program/Northern Right Whale Archived 8 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Maine.gov

- ^ a b North Atlantic Right Whale. Animal Info (2 November 2005)

- ^ ISBN 0-12-551340-2

- ^ WDC - Sperm Whale

- ^ Humpback Whale. Animal Info (1 February 2005)

- ISBN 9780292702417.

- ^ "Sei Whale Species Guide". Whale and Dolphin Conservation (WDC). Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-12-551340-1.

- ^ African Elephant Really Two Wildly Different Species. News.nationalgeographic.com (22 December 2010)

- ^ ADW: Loxodonta africana: Information. Animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu

- ^ Georges Frei. Weight and Size of elephants in zoo and circus. Upali.ch

- (PDF) from the original on 24 August 2016.

- ^ African Elephant. The Animal Files

- ^ a b Shoshani, J. and Eisenberg, J. F. Elephas maximus. Archived 30 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine Mammalian Species (1982) 182:1–8

- ^ a b Forest elephant videos, photos and facts – Loxodonta cyclotis Archived 24 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. ARKive

- ^ Forest Elephant Loxodonta cyclotis – Appearance/Morphology: Measurement and Weight (Literature Reports). Wildpro.twycrosszoo.org Archived 11 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "White Rhino - Species - WWF". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ White rhinoceros videos, photos and facts – Ceratotherium simum Archived 9 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine. ARKive (6 August 2004)

- ^ "African Rhinoceros". viuzza.net. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ White Rhinoceroses, White Rhinoceros Pictures, White Rhinoceros Facts. Animals.nationalgeographic.com

- ^ Indian rhinoceros videos, photos and facts – Rhinoceros unicornis Archived 4 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. ARKive

- ^ Laurie, W. A.; Lang, E. M. and Groves, C. P. Rhinocerus unicorns Archived 29 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Mammalian Species (1983) 211:1–6

- ISBN 978-0-671-42805-1

- ^ Indian rhinoceros Archived 26 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Ultimateungulate.com

- ISBN 0-85661-131-X.

- ^ Hippopotamus. Learnanimals.com

- ^ "Hippopotamus amphibius (hippopotamus)". Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ Hippopotamuses, Hippopotamus Pictures, Hippopotamus Facts. Animals.nationalgeographic.com

- ^ Black Rhinoceroses, Black Rhinoceros Pictures, Black Rhinoceros Facts. Animals.nationalgeographic.com

- S2CID 253955264.

- ^ ADW: Diceros bicornis: Information. (9 April 2009)

- ^ Javan Rhinoceros. Animal Info (26 November 2005)

- ^ Javan Rhino. Onehornedrhino.org Archived 13 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Javan rhinoceros videos, photos and facts – Rhinoceros sondaicus Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. ARKive

- ^ EDGE :: Mammal Species Information Archived 8 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine Edgeofexistence.org (12 November 2010)

- ISBN 978-0-521-42637-4

- ^ Giraffe. The Animal Files

- ^ ISBN 0691099847

- ^ Walrus: Physical Characteristics Archived 20 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Seaworld.org

- ^ "Largest mammal".

- ^ "Balaenoptera musculus (Blue whale)". Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ S2CID 2092950.

- doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1993.tb02560.x.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ "An Ancient Elephant May Have Been Biggest Land Mammal Ever". 17 July 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ a b St. Fleur, Nicholas (4 January 2019). "An Elephant-Size Relative of Mammals That Grazed Alongside Dinosaurs". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- S2CID 196679837.

- ^ a b Anteosaurus. Palaeos.com

- S2CID 133755506.

- ^ "Permian Stratigraphy – International Commission on Stratigraphy International Union of Geological Sciences" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- PMID 24739998.

- .

- PMID 24509889.

- ^ Olson, E.C. (1955). "Parallelism in the evolution of the Permian reptilian faunas of the Old and New Worlds". Fieldiana. 37 (13): 395. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- PMID 30467179.

- Science Daily. 23 November 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ Crocodilian Biology Database – FAQ – Which is the largest species of crocodile? Flmnh.ufl.edu

- ^ Boloji.com – A Study in Diversity Archived 30 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine. News.boloji.com

- ^ ""Lolong" holds world record as largest croc in the world". Protected Areas and Wildlife Bureau. 17 November 2011. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ Britton, Adam (12 November 2011). "Accurate length measurement for Lolong". Croc Blog. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ "NatGeo team confirms Lolong the croc is world's longest". GMA News Online. 9 November 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ "Philippine town claims world's largest crocodile title". The Telegraph. 9 November 2011. Archived from the original on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ "'Lolong' claims world's largest croc title". ABS-CBNnews.com. Agence France-Presse. 9 November 2011. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- .

- ^ a b "Saltwater Crocodile". National Geographic. 11 November 2010. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011.

- ^ "Crocodylus porosus- Salt-water Crocodile, Estuarine Crocodile". Australian Government- Department of the Environment. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ Grigg, G. & Gans, C. "Morphology & Physiology of Crocodylia" (PDF). Australian Government- Department of the Environment. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ "World's Top 5 Largest Crocodiles Ever Recorded". Our Planet. 16 December 2017.

- JSTOR 1564770.

- ^ a b c d "BBC Nature - Nile crocodile videos, news and facts".

- ^ Orinoco crocodile videos, photos and facts – Crocodylus intermedius Archived 5 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine. ARKive

- ^ WAZA. "Orinoco Crocodile". Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ Leatherback Sea Turtle. euroturtle.org Archived 3 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Client Validation". www.vanaqua.org. Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Jake Fishman. "ADW: Crocodylus acutus: INFORMATION". Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ ANIMAL BYTES – American Crocodile Archived 2 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Seaworld.org

- ^ "American Crocodile". National Geographic. 10 September 2010. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011.

- ^ http://www.myfwc.com/media/664081/AmericanCrocodilesinFL.pdf Archived 7 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Crocodilian Species – Black Caiman (Melanosucus niger). Crocodilian.com

- ^ "Black caiman videos, photos and facts - Melanosuchus niger - ARKive". Archived from the original on 4 February 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ SeaWorld Parks & Entertainment. "Caimans". Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ http://www.iucncsg.org/365_docs/attachments/protarea/06_M-24b37cab.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b "Gharial". Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ Gavials (Gharials), Gavial (Gharial) Pictures, Gavial (Gharial) Facts. Animals.nationalgeographic.com

- ^ a b "American Alligator". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ a b c "American Alligator". 25 April 2016.

- .

- ^ http://www.zoonegaramalaysia.my/RPFalseGharial.pdf Archived 27 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- PMID 28942308.

- ^ "Tomistoma Task Force". tomistoma.org.

- ^ Chris Ng. "ADW: Dipsochelys dussumieri: INFORMATION". Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ PMID 5160860.

- ^ "Information About Sea Turtles: Green Sea Turtle – Sea Turtle Conservancy". Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ a b c "African Slender-Snouted Crocodile - The Maryland Zoo in Baltimore". The Maryland Zoo in Baltimore.

- ^ ADW: Geochelone nigra: Information. Animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu

- ^ White Matt (18 August 2015). "2002: Largest Tortoise". Official Guinness World Records. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ San Diego Zoo's Animal Bytes: Galápagos Tortoise. Sandiegozoo.org

- S2CID 56028251.

- ^ Janensch, W. (1950). "The skeleton reconstruction of Brachiosaurus brancai". pp. 97–103.

- ^ Paul, G.S. (1988). "The brachiosaur giants of the Morrison and Tendaguru with a description of a new subgenus, Giraffatitan, and a comparison of the world's largest dinosaurs". Hunteria. 2 (3): 1–14.

- ^ PMID 24802911.

- S2CID 15220647.

- ^ "The World of Dinosaurs". Museum für Naturkunde. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ Morgan, James (17 May 2014). "BBC News - 'Biggest dinosaur ever' discovered". BBC News. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ^ "Giant dinosaur slims down... a bit". BBC News. 10 August 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ S2CID 53446536.

- ^ PMID 24204747.

- ^ a b "Volumetric analysis of Barosaurus' size". thesauropodomorphlair. 28 January 2020.

- ^ Mortimer, M. (2001), "Re: Bruhathkayosaurus" Archived 22 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine, discussion group, The Dinosaur Mailing List, 19 June 2001. Accessed 23 May 2008.

- S2CID 210840060.

- ^ Mortimer, M. (2001), "Re: Bruhathkayosaurus", discussion group, The Dinosaur Mailing List, 19 June 2001. Accessed 23 May 2008.

- ^ Mortimer, M. (2004), "Re: Largest Dinosaurs" Archived 13 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine, discussion group, The Dinosaur Mailing List, 7 September 2004. Accessed 23 May 2008.

- ^ S2CID 210840060.

- ^ Carpenter, K. (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus." In Foster, J.R. and Lucas, S.G., eds., 2006, Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36: 131–138.

- ^ Paul, G.S., 2016, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs 2nd edition, Princeton University Press p. 213

- ^ a b "The size of the BYU 9024 animal". svpow.com. 16 June 2019. Archived from the original on 16 April 2022.

- ^ PMID 26777391.

- ^ Paul, G.S. (1997). "Dinosaur models: the good, the bad, and using them to estimate the mass of dinosaurs" (PDF). In Wolberg, D.L.; Stump, E.; Rosenberg, G.D. (eds.). DinoFest International Proceedings. Dinofest International. The Academy of Natural Sciences. pp. 129–154. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ S2CID 210840060.

- ^ PMID 28794222.

- ^ a b Paul, G.S. (2016) The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. 2nd ed. Princeton University Press p. 206

- ^ Holtz, Tom (2012) Genus List for Holtz (2007) Dinosaurs

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R. (2014). "Supplementary Information to Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages".

- ^ Hartman, Scott (2013). "The biggest of the big". Skeletal Drawing. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Wedel, Mathew J.; Cifelli, R.L.; Sanders, R..K. (2000). "Osteology, paleobiology, and relationships of the sauropod dinosaur Sauroposeidon" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 45: 343–388. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- ^ Wedel, Mathew J.; Cifelli, Richard L. (Summer 2005). "Sauroposeidon: Oklahoma's Native Giant" (PDF). Oklahoma Geology Notes. 65 (2): 40–57. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2008.

- ^ PMID 26063751.

- PMID 22022500.

- ^ Hartman, Scott (7 July 2013). "Mass estimates: North vs South redux". Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- S2CID 85702490. Archived from the original(PDF) on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ S2CID 86025320.

- S2CID 34421257.

- ^ "Discoveries - Paul Sereno - Paleontologist - The University of Chicago". paulsereno.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- S2CID 30701725.

- ^ Coria, R. A. and Currie, P. J. (2006). "A new carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina". Geodiversitas, 28 (1): 71–118. pdf link Archived 2 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix.

- S2CID 39658297.

- ^ Chemistry - Stegosaurus. Chemistrydaily.com Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ankylosaurus Facts. sciencekids.co.nz

- S2CID 119700784.

- ^ JSTOR 1304231.

- ISBN 978-0-691-02882-8.

- .

- doi:10.1139/E07-011.

- ^ a b birding.com records Archived 2 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Avian Medicine: Principles and Application. avianmedicine.net Archived 19 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- PMID 30839722.

- ISBN 978-0-253-34282-9

- ISBN 978-0-470-65666-2

- PMID 17609382.

- ^ PMID 25002475.

- ^ Osborne, Hannah (7 July 2014). "Pelagornis Sandersi: World's Biggest Bird Was Twice as Big as Albatross with 24ft Wingspan". ibtimes.co.uk. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-854996-3

- ^ ISBN 978-84-87334-10-8

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- ^ ISBN 0-8069-4232-0

- ^ Ramsey, Tanya Lewis, Lydia. "The turkeys we eat today weigh twice as much as they did a few decades ago". Business Insider.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Turkey Facts - Turkey for Holidays - University of Illinois Extension". extension.illinois.edu. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ ISBN 84-87334-20-2.

- ^ Leopard Seals Group Penguin Slideshow Ppt Presentation Archived 18 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Authorstream.com (31 March 2009)

- ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^ Cox, C. B.; Hutchinson, P. (1991). "Fishes and amphibians from the Late Permian Pedrado Fogo Formation of northern Brazil" (PDF). Palaeontology. 34: 561–573. INIST 19854877. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2012.

- ^ African Bullfrog. Honoluluzoo.org Archived 3 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Giant "Frog From Hell" Fossil Found in Madagascar. News.nationalgeographic.com (28 October 2010)

- PMID 24489877.

- ^ White Lipped Tree Frog. The Animal Files

- ^ Surinam horned frog (Ceratophrys cornuta) – Videos Peru – Peru Videos. Bullafina.com (11 June 2008) [dead link]

- ^ Golden Poison Dart Frogs, Golden Poison Dart Frog Pictures, Golden Poison Dart Frog Facts. Animals.nationalgeographic.com

- ISBN 0-12-178560-2.

- ^ Platt, John R. "Swampy Thing: The Giant New Salamander Species Discovered in Florida and Alabama". Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ The Largest Newt As a Pet. Buzzle.com

- ^ a b André, Frédéric; Tourenne, Murielle; Foveau, Aurélie (8 August 2011). "Synoicum pulmonaria (Ellis & Solander, 1786)" (in French). DORIS. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- PMID 9084635.

- ^ "Pyura". Biosecurity in New Zealand. Ministry for Primary Industries, New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ISBN 978-81-315-0104-7.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b Cyclosalpa bakeri - Ritter, 1905 Archived 21 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine JelliesZone, by David Wrobel. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ Pyrosoma atlanticum Marine Species Identification Portal. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ Doliolida World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ Pelagic Tunicates Archived 23 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine JelliesZone, by David Wrobel. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ Branchiostoma lanceolatum Marine Species Information Portal. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ a b Mah, Christopher (27 July 2008). "What Are the World's LARGEST Starfish?". The Echinoblog.

- ISBN 0-8118-4633-4p. 129

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7565-1611-6.

- ^ "Strongylocentrotus franciscanus". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ "Long-spined black sea urchin". Wild Singapore. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ Mah, Christopher (27 April 2009). "The World's BIGGEST Brittle Stars!". The Echinoblog.

- ^ "Neoentobdella gen. nov for species of Entobdella Blainville in Lamarck, 1818 (Monogenea, Capsalidae, Entobdellinae) from stingray hosts, with descriptions of two new species" (PDF). Acta Parasitologica. 50 (1): 32–48. 2005.

- ^ DPDx – Fasciolopsiasis. Dpd.cdc.gov Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Time Magazine(8 April 1957)

- ^ Hargis, William J. Parasitology and pathology of marine organisms of the world ocean Archived 15 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (1985)

- ^ The Mighty Worm. Worm Digest (2 October 2005) Archived 19 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Carwardine, M. 1995. The Guinness Book of Animal Records. Guinness Publishing. p. 232.

- ^ Photo in the News: Colossal Squid Caught off Antarctica. News.nationalgeographic.com (28 October 2010)

- ^ "The UnMuseum - The Colossal Squid". www.unmuseum.org. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Kathy Marks. NZ's colossal squid to be microwaved Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. The New Zealand Herald (23 March 2007)

- ^ "How big is the colossal squid?". Te papa. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008.

- ^ Giant Squids, Architeuthis dux. Marinebio.org

- ^ Giant Squid, Giant Squid Pictures, Giant Squid Facts. Animals.nationalgeographic.com (4 December 2006)

- ^ O'Shea, S. 2003. "Giant Squid and Colossal Squid Fact Sheet". The Octopus News Magazine Online.

- .

- ^ Gumboot Chiton. alaska.gov

- S2CID 130048023.

- ^ John D. Taylor and Emily A. Glover. Food of giants – field observations on the diet of Syrinx aruanus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Turbinellidae) the largest living gastropod, in F. E. Wells, D. I. Walker and D. S. Jones (eds.) 2003. The Marine Flora and Fauna of Dampier, Western Australia. Western Australian Museum, Perth.

- ^ Largest snails in the world – Giant African snail. largestfastestsmartest.co.uk

- hdl:1828/12155.

- ^ [Octopus – Species].[full citation needed]

- PMID 14822893. Archived from the original(PDF) on 15 December 2013.

- ^ Natural History Collections: Nematoda. Nhc.ed.ac.uk

- S2CID 6456946.

- PMID 18029297.

- ^ "First Contact". panda.org. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Poisonous Animals: Tarantula (Grammostola, Phrixothrichus). Library.thinkquest.org

- S2CID 131416804.

- JSTOR 1302906.

- ISBN 978-0-520-26140-2.

- Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. 17: 1–286. Archived from the original(PDF) on 6 June 2011.

- ^ D. R. Currie; T. M. Ward (2009). South Australian Giant Crab (Pseudocarcinus gigas) Fishery (PDF). South Australian Research and Development Institute. Fishery Assessment Report for PIRSA. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ Roy Caldwell. "Species: Lysiosquillina maculata". Roy's List of Stomatopods for the Aquarium. University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ "Tasmanian Giant Freshwater Lobster (Astacopsis gouldi)". Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. 9 February 2007. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- .

- ^ Branchinecta gigas (crustacean). Britannica Online Encyclopaedia

- ^ Pennella balaenopterae. Animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu

- ^ Giant Acorn Barnacle. Oregon Coast Aquarium Archived 9 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Knight, J.D. Giant Isopod – Deep Sea Creatures on Sea and Sky. Seasky.org

- ^ Remipedia: Species – robustus, Godzillius. Crustacea.net (2 October 2002)

- ^ Horseshoe Crabs, Limulus polyphemus at. Marinebio.org

- ^ Sea spiders Facts, information, pictures. work=Encyclopedia.com (22 October 2004)

- .

- ^ Giant Trilobites in Portugal Could Be Biggest Portugal – Discovery News. Dsc.discovery.com (7 May 2009). Archived 10 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Scolopendra gigantea. Arachnoboards.com (13 August 2003)

- ISBN 978-0122268656. Archived from the original(PDF) on 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Largest". Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)(2011). source: The University of Florida Book of Insect Records "Largest". Archived from the original on 20 August 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2009. - ^ Creature Features – Giant Burrowing Cockroach Archived 18 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Abc.net.au

- ^ The Giant Earwig of St. Helena Labidura herculeana. Earwig Research Centre. Earwigs-online.de

- ^ Trust), David Pryce (St Helena National; Liza White (Environment and Natural Resources Directorate, St Helena Government) (22 August 2014). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Labidura herculeana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- ^ "Gone for good: world's largest earwig declared extinct". Mongabay Environmental News. 19 November 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Madagascan mayfly hyper-diversity. The BioFresh blog (24 May 2011)

- ^ P. J. Perez-Goodwyn (2006). Taxonomic revision of the subfamily Lethocerinae Lauck & Menke (Heteroptera: Belostomatidae)". Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde. A (Biologie) 695: 1–71.

- ^ Haddad Jr; Schwartz; Schwartz; and Carvalho (2010). Bites Caused by Giant Water Bugs Belonging to Belostomatidae Family (Hemiptera, Heteroptera) in Humans: A Report of Seven Cases. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine 21: 130–133.

- ^ BBC News (26 May 2011). Giant water bug photographed devouring baby turtle. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ISBN 0-7614-7270-3

- ISBN 978-3540301462

- ^ Giant Oak Aphid hunt is on. The Telegraph (8 August 2007)

- ^ Ledromorpha planirostris Archived 14 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Bugs.bio.usyd.edu.au

- ISBN 978-1-405-15142-9

- ISBN 3-540-30146-1

- ^ Live Pet Mantis Hobby Archived 4 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Bugsincyberspace.com

- ISBN 978-0-553-59256-6.

- ^ "Scorpion Flies - Panorpa communis - UK Safari". www.uksafari.com.

- ^ Dobsonfly. Real Monstrosities (26 January 2011)

- ^ Palparellus voeltzkowi (Kolbe, 1906). Researcharchive.calacademy.org

- ^ Bio-Ditrl, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- S2CID 86240200.

- .

- ^ Giant Grasshoppers – The largest grasshopper – Valanga irregularis. Brisbaneinsects.com

- ^ Eastern Lubber Grasshopper – Florida eco travel guide. Wildflorida.com

- ^ Giant Long-Legged Katydid Archived 7 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Hmns.org

- ^ "Longest Insect discovered in China". Archived from the original on 8 May 2016.

- ISBN 9780643094185.

- ^ "World's longest insect revealed". Natural History Museum. 16 October 2008. Archived from the original on 19 October 2008. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- ^ Seow-Choen, F. (1995). The longest insect in the world. Malayan Nat. 48: 12.

- ISSN 1175-5326. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- ^ Brock, P.D. 1999. The amazing world of stick and leaf-insects. Cravitz Printing Co., Essex, England.

- ^ Seow-Choen, F. (1995). "The longest insect in the world". Malayan Nat. 48: 12.

- ^ ADW: Haematopinus suis: Information. Animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu

- ^ Pteronarcys californica – aka Giant Stonefly or Giant Salmonfly. Riverwood Blog – Fly Fishing Gear & Guided Fishing Trips in Oregon (20 April 2009) Archived 2 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ National Barkfly (Outdoor Psocoptera) Recording Scheme. Brc.ac.uk

- ^ List of largest insects. Paulsquiz.com Archived 14 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Diptera.info – Discussion Forum: The LARGEST caddisfly of the world.

- ISBN 978-1-118-94560-5.

- ^ Engel, Michael S. (2005). "Zoraptera". Tree of Life Web Project. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ Rare sighting of a lion’s mane jellyfish in Tramore Bay. waterford-today.ie

- ^ "Lion's Mane Jellyfish". jellyfishfacts.net. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Sea Anemones, Sea Anemone Pictures Archived 16 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Northrup.org

- ^ Tube Anemones – Ceriantharia. Seawater.no

- ^ Praya picture. Lifesci.ucsb.edu

- ^ Portuguese Man-of-Wars, Portuguese Man-of-War Pictures, Portuguese Man-of-War Facts. Animals.nationalgeographic.com

- ^ "Longest Giant Stringy Sea Creature Ever Recorded Looks like It Belongs in Outer Space". interestingengineering.com. 9 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- EurekAlert!. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Biggest, Smallest, Fastest, Deepest: Marine Animal Records – Marine Biology: Life in the Ocean. Care2.com (4 March 2009)

- ^ Xestospongia muta. Encyclopedia of Life

- Wikidata Q56915355.