Philip I Philadelphus

| Philip I Philadelphus | |

|---|---|

Antiochus XIII, Cleopatra Selene | |

| Born | between 124 and 109 BC |

| Died | 83 or 75 BC |

| Issue | Philip II |

| Dynasty | Seleucid |

| Father | Antiochus VIII |

| Mother | Tryphaena |

Philip I Epiphanes Philadelphus (

After the murder of Seleucus VI in 94 BC, Philip I became king with his twin brother

Philip I tried unsuccessfully to take Damascus for himself, after which he disappears from the historical record; there is no information about when or how he died. The Antiochenes, apparently refusing to accept Philip I's minor son

Background, name and early life

The

With his Ptolemaic wife

Reign

Philip I and Antiochus XI probably resided in Cilicia during Seleucus VI's reign.[21] In 94 BC, shortly after their brother's death, Philip I and Antiochus XI minted jugate coins with their portraits on the obverse.[11] The historian Alfred Bellinger suggested that their base of operations was a coastal city north of Antioch,[22] but according to the numismatist Arthur Houghton, Beroea is a stronger candidate because the city's rulers were Philip I's allies.[23] All the jugate coins were minted in Cilicia; the series with the most numerous surviving specimens was probably issued in Tarsus, making it the likely base of operations.[24] Antiochus XI was portrayed in front of his brother, indicating that he was the senior king.[note 2][25] Deriving their legitimacy from Antiochus VIII, the brothers were depicted on the coins with exaggerated aquiline noses similar to their father.[26] Hellenistic kings did not use regnal numbers, which is a modern practise; instead, they used epithets to distinguish themselves from similarly named monarchs.[27][28] On his coins, Philip I used the epithets Philadelphus (sibling-loving) and Epiphanes (the glorious, or illustrious).[29] The brothers intended to avenge Seleucus VI;[note 3][11] according to the fourth century writer Eusebius, they sacked Mopsuestia and destroyed it.[note 4][10]

Reign in Cilicia and Beroea

While Philip I remained in Cilicia, Antiochus XI advanced on Antioch and drove Antiochus X from the city in the beginning of 93 BC.[24] Philip I did not live in the Syrian metropolis and left Antiochus XI as master of the capital.[note 5][32] By autumn 93 BC, Antiochus X regrouped and defeated Antiochus XI, who drowned in the Orontes.[11] The first century historian Josephus mentioned only Antiochus XI in the battle, but Eusebius wrote that Philip I was also present. Bellinger believed that Philip I's troops participated, but that he remained behind at his base, since only Antiochus XI was killed.[25] Following the defeat, Philip I is thought to have retreated to his capital, which was probably the same base from which he and his brother operated when they first prepared to avenge Seleucus VI.[33] Antiochus X eventually controlled Cilicia,[13] and Philip I probably took Beroea as his base.[34]

Demetrius III may have marched north to support Antiochus XI in the battle of 93 BC,[35] and he certainly supported Philip I in the struggle against Antiochus X.[36] Eusebius wrote that Philip I defeated Antiochus X and replaced him in the capital in 93/92 BC (220 SE (Seleucid year)).[note 6] However, Eusebius does not note the reign of Antiochus XI or mention Demetrius III.[10] The account contradicts archaeological evidence, represented in a market weight belonging to Antiochus X from 92 BC, and contains factual mistakes.[38] The English minister and numismatist Edgar Rogers believed that Philip I ruled Antioch immediately after Antiochus XI,[39] but suggestions that Philip I controlled Antioch before the demise of Antiochus X and Demetrius III can be dismissed; they contradict the numismatic evidence, and no ancient source claimed that Demetrius III, who actually succeeded Antiochus X in Antioch, had to push Philip I out of the city.[34]

In any case, Antiochus X disappeared from the record after 92 BC,[38] but could have remained in power until 224 SE (89/88 BC);[34] he probably died fighting against Parthia.[note 7] Taking advantage of Antiochus X's death, Demetrius III rushed to the capital and occupied it;[42] this led Philip I to break his alliance with his brother.[12] With most of Syria in the hands of Demetrius III, Philip I retreated to his base.[note 8][12] In 88 BC, Demetrius III marched on Beroea for the final battle with Philip I.[12] To raise the siege, Philip I's ally Straton, the ruler of Beroea, called on the Arab phylarch Aziz and the Parthian governor Mithridates Sinaces for help. The allies defeated Demetrius III, who was sent into captivity in Parthia. Any captive who was a citizen of Antioch was released without a ransom, a gesture which must have eased Philip I's occupation of Antioch.[44]

Reign in the capital

Shortly after the battle, in late 88 BC or early 87 BC, Philip I entered the Syrian capital,[12] and had Cilicia under his authority.[45] He was faced with the need to replenish the empty treasury to rebuild a country destroyed after years of civil war, and in case a new pretender to the throne arose.[46] Those factors, combined with the low estimates of annual coin dies used by Philip I's immediate predecessors in Antioch—Antiochus X (his second reign) and Demetrius III—compared with the general die estimates of late Seleucid kings, led numismatist Oliver D. Hoover to propose that Philip I simply re-coined his predecessors' coins and skewed their dies.[47] This resulted in currency bearing Philip I's image, reduced in weight from the standard 1,600 g (56 oz) to 1,565 g (55.2 oz). This yielded a profit of half an obol on each older coin which was re-struck.[48] Profit was, however, not the main aim of Philip I; it is more probable that he wanted to pay his troops with coins bearing his own image instead of that of his rivals. The recoinage was also necessary since Philip I's coins were reduced in weight and the king needed to enforce the use of his currency by removing his rivals' heavier coins out of circulation.[49] Philip I may have adopted the New Seleucid era dating, which have the return of Antiochus VIII from his exile in Aspendos in 200 SE (113/112 BC) as a starting point;[50][16] the traditional Seleucid era started in 1 SE (312/311 BC).[37]

Philip I's position on the throne was insecure: Cleopatra Selene hid in Syria with

End and succession

After the attack on Damascus, Philip I disappeared from ancient literature. Without proof, 83 BC is commonly accepted as Philip I's year of death by most scholars;

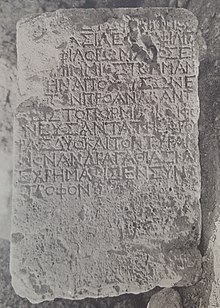

- Escaped to Cilicia: An inscription of Philip II was found in Mithridates VI of Pontus and Rome. Another possibility is that Philip I was preparing to take back his throne after the death of Antiochus XII (d. 82 BC), but was caught off guard by the arrival of Tigranes II and put to death in Cilicia.[59] Historian Theodora Stillwell MacKay suggested that Philip I fled to Olba following his confrontation with Antiochus XII.[58] The epigraphers Josef Keil and Adolf Wilhelm suggested that Philip I stayed with the priest-prince of the city.[60]

- Peaceful long reign: according to Bellinger, the silence of ancient literature might be an indication of a peaceful reign that was perhaps facilitated by Philip I's alliance with Parthia; this would explain the massive amount of silver coinage produced by Philip I found as far as Dura-Europos, which was under Parthian rule.[61] Appian's account is flawed, and contradicts contemporary accounts, notably the Roman statesman Cicero, who wrote in 75 BC that Cleopatra Selene sent Antiochus XIII to Rome to appeal for his right to the Egyptian throne; he did not have to appeal for his rights to Syria which, in the words of Cicero, he inherited from his ancestors.[62] Cleopatra Selene and her son probably took advantage of Antiochus XII's death in 82 BC to assume control of the south;[63][64] the statement of Cicero indicates that in 75 BC, Tigranes II was still not in control of Syria, for if he were, Antiochus XIII would have asked the Roman Senate for support to regain Syria, since Tigranes II was the son-in-law of Rome's enemy, Mithridates VI. Likewise, Philip I could not have been alive since Antiochus XIII went to Rome without having to assert his right to Syria.[62][49]

- The argument for a later Armenian invasion is corroborated by Josephus, who wrote that the Jews heard about the Armenian invasion and Tigranes II's plans to attack Judea only during the reign of the Hasmonean queen Salome Alexandra, which began in 76 BC; it would be odd if Tigranes II took control of Syria in 83 BC and the Jews learned about it only after 76 BC.[54] Another point of argument is the massive quantity of coinage left by Philip I, which could not have been produced if his reign was short and ended in 83 BC.[65] In light of this, Hoover proposed 75 BC, or slightly earlier, as Philip I's last year; this would be in line with Cicero's statement about Antiochus XIII. Hoover suggested the year 74 BC as the date of Tigranes II's invasion, giving Cleopatra Selene and her son time to claim the whole country.[note 11][67]

Legacy

Philip I's coins were still in circulation when the Romans annexed Syria in 64 BC.[68] The first Roman coins struck in Syria were copies of Philip I's coins, and bore his image with the monogram of the Roman governor.[69] The first issue was in 57 BC under governor Aulus Gabinius,[70] and the last series of Philip I's posthumous coins was minted in 13 BC.[69] The Romans may have considered Philip I the last legitimate Seleucid king, a theory held by Kevin Butcher and other scholars.[71] Hoover opted for a simpler answer; Philip I's coins were the most numerous and earlier Seleucid coin models were destroyed, making it economically sensible for the Romans to continue Philip I's model.[72] Anomalous coins of Philip, differing from his standard lifetime models but similar to the later Roman Philip coins, indicate that they might have been minted by the autonomous city of Antioch between 64 and 58 BC before governor Aulus Gabinius issued his Philipean coins, making it viable for the Romans to continue minting coins already being struck.[73]

Family tree

| Family tree of Philip I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Citations:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- List of Syrian monarchs

- List of Seleucid rulers

- Timeline of Syrian history

Notes

- ^ Philip I's parents were identified as Antiochus VIII and Tryphaena by the fourth century historian Eusebius, who noted that Antiochus XI and Philip I were twins (didymi).[10]

- ^ According to Josephus, only Antiochus XI became king and Philip I succeeded him; numismatic evidence opposes this statement, since the earliest coins show Philip I and Antiochus XI as joint rulers.[25]

- ^ The earliest coins show the monarchs bearded, a possible sign of mourning or vengeance.[30]

- Sarapis in Mopsuestia (evidenced by a dated inscription found in the city), weakening the credibility of Eusebius' account.[31]

- ^ Eusebius does not note Antiochus XI's reign in Antioch, and the occupation of the capital by Antiochus XI in 93 BC is known only through the coins he struck in it.[25]

- ^ Some dates in the article are given according to the Seleucid era which is indicated when two years have a slash separating them. Each Seleucid year started in the late autumn of a Gregorian year; thus, a Seleucid year overlaps two Gregorian ones.[37]

- ^ Josephus wrote, "Both these brothers did Antiochus vehemently oppose, but presently died; for when he was come as an auxiliary to Laodice, queen of the Gileadites, when she was making war against the Parthians, and he was fighting courageously, he fell, while Demetrius and Philip governed Syria".[40] The Parthians might have been allied with Philip I.[41]

- ^ Coins of Demetrius III were struck in Tarsus, Seleucia Pieria, Antioch and Damascus.[43]

- Seleucus I, in a mausoleum named the Nikatoreion in Seleucia Pieria; no literary or archaeological evidence exist for the burial locations of other Seleucid kings, but it is possible that they were buried in the Nikatoreion.[55]

- ^ Eusebius and Jerome conflated the fate of Philip I with that of his son Philip II claiming that Philip I was captured by the Roman governor of Syria Aulus Gabinius.[54]

- ^ Cleopatra Selene and her son never controlled Antioch, but possessed parts of Syria.[66]

References

Citations

- ^ Marciak 2017, p. 8.

- ^ Goodman 2005, p. 37.

- ^ Tinsley 2006, p. 179.

- ^ Whitehorne 1994, pp. 149, 151, 154.

- ^ Kelly 2016, p. 82.

- ^ Kosmin 2014, p. 23.

- ^ Otto & Bengtson 1938, pp. 103, 104.

- ^ Chrubasik 2016, p. XXIV.

- ^ a b Houghton & Müseler 1990, p. 61.

- ^ a b c Eusebius 1875, p. 261.

- ^ a b c d Houghton 1987, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d e Houghton 1987, p. 81.

- ^ a b Lorber & Iossif 2009, p. 103.

- ^ Bazarnik 2010, p. 123.

- ^ Bevan 2014, p. 56.

- ^ a b Wright 2012, p. 11.

- ^ Dumitru 2016, p. 260.

- ^ Hoover 2007, p. 285.

- ^ Dumitru 2016, p. 263.

- ^ Houghton 1998, p. 66.

- ^ Bevan 1902, p. 260.

- ^ Bellinger 1949, p. 93.

- ^ Houghton 1987, p. 82.

- ^ a b Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 573.

- ^ a b c d Bellinger 1949, p. 74.

- ^ Wright 2011, p. 46.

- ^ McGing 2010, p. 247.

- ^ Hallo 1996, p. 142.

- ^ Gillies 1820, p. 167.

- ^ Hoover, Houghton & Veselý 2008, p. 207.

- ^ Rigsby 1996, p. 466.

- ^ Bellinger 1949, pp. 74, 93.

- ^ Bellinger 1949, p. 93, 92.

- ^ a b c Hoover 2007, p. 294.

- ^ a b c Hoover, Houghton & Veselý 2008, p. 214.

- ^ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 581.

- ^ a b Biers 1992, p. 13.

- ^ a b Hoover 2007, p. 290.

- ^ Rogers 1919, p. 32.

- ^ Josephus 1833, p. 421.

- ^ Wright 2012, p. 12.

- ^ Hoover 2007, p. 295.

- ^ Dąbrowa 2010, p. 177.

- ^ Downey 2015, pp. 134, 135.

- ^ Houghton 1998, p. 67.

- ^ Hoover 2011, p. 259.

- ^ a b Hoover 2011, pp. 259, 260.

- ^ Hoover 2011, p. 260.

- ^ a b Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 596.

- ^ Rogers 1919, p. 31.

- ^ Josephus 1833, p. 422.

- ^ Lorber & Iossif 2009, p. 112.

- ^ Lorber & Iossif 2009, p. 104.

- ^ a b c d Hoover 2007, p. 296.

- ^ a b Canepa 2010, p. 9.

- ^ Bellinger 1949, pp. 79, 80.

- ^ Bouché-Leclercq 1913, p. 426.

- ^ a b MacKay 1968, p. 91.

- ^ Bouché-Leclercq 1913, pp. 426, 427.

- ^ Keil & Wilhelm 1931, p. 66.

- ^ Bellinger 1949, p. 79.

- ^ a b Hoover 2007, p. 297.

- ^ Wright 2012, p. 33.

- ^ Burgess 2004, p. 21.

- ^ Hoover 2004, p. 31.

- ^ Bellinger 1949, p. 81.

- ^ Hoover 2007, pp. 297, 298.

- ^ Butcher & Ponting 2014, p. 541.

- ^ a b Butcher & Ponting 2014, p. 542.

- ^ Crawford 1985, p. 203.

- ^ Butcher 2003, p. 215.

- ^ Hoover 2011, p. 263.

- ^ Hoover 2004, pp. 34, 35.

Sources

- Bazarnik, Katarzyna (2010). "Chronotope in Liberature". In Bazarnik, Katarzyna; Kucała, Bożena (eds.). James Joyce and After: Writer and Time. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-443-82247-3.

- Bellinger, Alfred R. (1949). "The End of the Seleucids". Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. 38. Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. OCLC 4520682.

- Bevan, Edwyn Robert (1902). The House of Seleucus. Vol. II. London: Edward Arnold. OCLC 499314408.

- Bevan, Edwyn (2014) [1927]. A History of Egypt under the Ptolemaic Dynasty. Routledge Revivals. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-68225-7.

- Biers, William R. (1992). Art, Artefacts and Chronology in Classical Archaeology. Approaching the Ancient World. Vol. 2. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-06319-7.

- Bouché-Leclercq, Auguste (1913). Histoire Des Séleucides (323-64 avant J.-C.) (in French). Ernest Leroux. OCLC 558064110.

- Burgess, Michael Roy (2004). "The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress– The Rise and Fall of Cleopatra II Selene, Seleukid Queen of Syria". The Celator. 18 (3). Kerry K. Wetterstrom. ISSN 1048-0986.

- Butcher, Kevin (2003). Roman Syria and the Near East. The British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-2235-9.

- Butcher, Kevin; Ponting, Matthew (2014). The Metallurgy of Roman Silver Coinage: From the Reform of Nero to the Reform of Trajan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02712-1.

- Canepa, Matthew P. (2010). "Achaemenid and Seleucid Royal Funerary Practices and Middle Iranian Kingship". In Börm, Henning; Wiesehöfer, Josef (eds.). Commutatio et Contentio. Studies in the Late Roman, Sasanian, and Early Islamic Near East: in Memory of Zeev Rubin. Reihe Geschichte. Vol. 3. Wellem. ISSN 2190-0256.

- Chrubasik, Boris (2016). Kings and Usurpers in the Seleukid Empire: The Men who Would be King. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-198-78692-4.

- Crawford, Michael Hewson (1985). Coinage and Money Under the Roman Republic: Italy and the Mediterranean Economy. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05506-3.

- Dąbrowa, Edward (2010). "Demetrius III in Judea". Electrum. 18. Instytut Historii. Uniwersytet Jagielloński. ISSN 1897-3426.

- Downey, Robert Emory Glanville (2015) [1961]. A History of Antioch in Syria from Seleucus to the Arab Conquest. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-400-87773-7.

- Dumitru, Adrian (2016). "Kleopatra Selene: A Look at the Moon and Her Bright Side". In Coşkun, Altay; McAuley, Alex (eds.). Seleukid Royal Women: Creation, Representation and Distortion of Hellenistic Queenship in the Seleukid Empire. Historia – Einzelschriften. Vol. 240. Franz Steiner Verlag. ISSN 0071-7665.

- Eusebius (1875) [c. 325]. Schoene, Alfred (ed.). Eusebii Chronicorum Libri Duo (in Latin). Vol. 1. Translated by Petermann, Julius Heinrich. Apud Weidmannos. OCLC 312568526.

- Gillies, John (1820) [1786]. The History of Ancient Greece: Its Colonies, and Conquests. Part the Second, Embracing the History of the Ancient World, from the Dominion of Alexander to that of Augustus, with a Survey of Preceding Periods, and a Continuation of the History of Arts and Letters. Vol. IV (New: With Corrections and Additions ed.). T. Cadell & W. Davies. OCLC 1001209411.

- Goodman, Martin (2005) [2002]. "Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period". In Goodman, Martin; Cohen, Jeremy; Sorkin, David Jan (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-28032-2.

- Hallo, William W. (1996). Origins. The Ancient Near Eastern Background of Some Modern Western Institutions. Studies in the History and Culture of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 6. Brill. ISSN 0169-9024.

- Hoover, Oliver D. (2000). "A Dedication to Aphrodite Epekoos for Demetrius I Soter and His Family". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 131. Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH. ISSN 0084-5388.

- Hoover, Oliver D. (2004). "Anomalous Tetradrachms of Philip I Philadelphus struck by Autonomous Antioch (6458 BC)". Schweizer Münzblätter. 54 (214). Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Numismatik. ISSN 0016-5565.

- Hoover, Oliver D. (2007). "A Revised Chronology for the Late Seleucids at Antioch (121/0–64 BC)". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 56 (3). Franz Steiner Verlag: 280–301. S2CID 159573100.

- Hoover, Oliver D.; Houghton, Arthur; Veselý, Petr (2008). "The Silver Mint of Damascus under Demetrius III and Antiochus XII (97/6 BC–83/2 BC)". American Journal of Numismatics. Second series. 20. American Numismatic Society. ISSN 1053-8356.

- Hoover, Oliver D. (2011). "A Second Look at Production Quantification and Chronology in the Late Seleucid Period". In de Callataÿ, François (ed.). Time is Money? Quantifying Monetary Supplies in Greco-Roman Times. Pragmateiai. Vol. 19. Edipuglia. ISSN 2531-5390.

- Houghton, Arthur (1987). "The Double Portrait Coins of Antiochus XI and Philip I: a Seleucid Mint at Beroea?". Schweizerische Numismatische Rundschau. 66. Schweizerischen Numismatischen Gesellschaft. ISSN 0035-4163.

- Houghton, Arthur; Müseler, Wilhelm (1990). "The Reigns of Antiochus VIII and Antiochus IX at Damascus". Schweizer Münzblätter. 40 (159). Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Numismatik. ISSN 0016-5565.

- Houghton, Arthur (1998). "The Struggle for the Seleucid Succession, 94–92 BC: a New Tetradrachm of Antiochus XI and Philip I of Antioch". Schweizerische Numismatische Rundschau. 77. Schweizerischen Numismatischen Gesellschaft. ISSN 0035-4163.

- Houghton, Arthur; Lorber, Catherine; Hoover, Oliver D. (2008). Seleucid Coins, A Comprehensive Guide: Part 2, Seleucus IV through Antiochus XIII. Vol. 1. The American Numismatic Society. OCLC 920225687.

- Josephus (1833) [c. 94]. OCLC 970897884.

- Keil, Josef; Wilhelm, Adolf (1931). Denkmäler aus dem Rauhen Kilikien. Monumenta Asiae Minoris Antiqua (in German). Vol. III. Manchester: The University Press. OCLC 769301925.

- Kelly, Douglas (2016). "Alexander II Zabinas (Reigned 128–122)". In Phang, Sara E.; Spence, Iain; Kelly, Douglas; Londey, Peter (eds.). Conflict in Ancient Greece and Rome: The Definitive Political, Social, and Military Encyclopedia (3 Vols.). Vol. I. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-610-69020-1.

- Kosmin, Paul J. (2014). The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in the Seleucid Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0.

- Lorber, Catharine C.; Iossif, Panagiotis (2009). "Seleucid Campaign Beards". L'Antiquité Classique. 78. l’asbl L’Antiquité Classique. ISSN 0770-2817.

- MacKay, Theodora Stillwell (1968). Olba in Rough Cilicia. Bryn Mawr College. OCLC 14582261.

- Marciak, Michał (2017). Sophene, Gordyene, and Adiabene. Three Regna Minora of Northern Mesopotamia Between East and West. Impact of Empire. Vol. 26. Brill. ISSN 1572-0500.

- McGing, Brian C. (2010). Polybius' Histories. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-71867-2.

- Ogden, Daniel (1999). Polygamy, Prostitutes and Death: The Hellenistic Dynasties. Duckworth with the Classical Press of Wales. ISBN 978-0-715-62930-7.

- Otto, Walter Gustav Albrecht; Bengtson, Hermann (1938). Zur Geschichte des Niederganges des Ptolemäerreiches: ein Beitrag zur Regierungszeit des 8. und des 9. Ptolemäers. Abhandlungen (Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-Historische Klasse) (in German). Vol. 17. Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. OCLC 470076298.

- Rigsby, Kent J. (1996). Asylia: Territorial Inviolability in the Hellenistic World. Hellenistic Culture and Society. Vol. 22. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20098-2.

- Rogers, Edgar (1919). "Three Rare Seleucid Coins and their Problems". The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society. fourth. 19. Royal Numismatic Society. ISSN 2054-9199.

- Tinsley, Barbara Sher (2006). Reconstructing Western Civilization: Irreverent Essays on Antiquity. Susquehanna University Press. ISBN 978-1-575-91095-6.

- Whitehorne, John (1994). Cleopatras. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05806-3.

- Wright, Nicholas L. (2011). "The Iconography of Succession Under the Late Seleukids". In Wright, Nicholas L. (ed.). Coins from Asia Minor and the East: Selections from the Colin E. Pitchfork Collection. The Numismatic Association of Australia. ISBN 978-0-646-55051-0.

- Wright, Nicholas L. (2012). Divine Kings and Sacred Spaces: Power and Religion in Hellenistic Syria (301-64 BC). British Archaeological Reports (BAR) International Series. Vol. 2450. Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-407-31054-1.

External links

- The biography of Philip I in the website of the numismatist Petr Veselý.