List of 2022 FIFA World Cup controversies: Difference between revisions

59,845 edits →England 1–2 France: Tchouaméni 17': refs + "some" (to not generalise) |

59,845 edits No edit summary |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

{{EngvarB|date=November 2022}} |

{{EngvarB|date=November 2022}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=April 2022}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=April 2022}} |

||

{{2022 FIFA World Cup sidebar}} |

|||

The awarding of the [[2022 FIFA World Cup]] to [[Qatar]] created a number of concerns and controversies regarding both Qatar's suitability as a host country and the fairness of the [[2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cup bids|FIFA World Cup bidding process]].<ref name="Atlantic 2022">{{cite magazine |author-last=McTague |author-first=Tom |date=19 November 2022 |title=The Qatar World Cup Exposes Soccer's Shame |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2022/11/qatar-hosting-fifa-world-cup-soccer/672171/ |url-status=live |magazine=[[The Atlantic]] |location=Washington, D.C. |publisher=[[Emerson Collective]] |issn=2151-9463 |oclc=936540106 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221119231915/https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2022/11/qatar-hosting-fifa-world-cup-soccer/672171/ |archive-date=19 November 2022 |access-date=20 November 2022}}</ref><ref name="Reason 2022">{{cite magazine |last=Boehm |first=Eric |date=21 November 2022 |title=The Qatar World Cup Is a Celebration of Authoritarianism |url=https://reason.com/2022/11/21/the-qatar-world-cup-is-a-celebration-of-authoritarianism/ |url-status=live |magazine=[[Reason (magazine)|Reason]] |publisher=[[Reason Foundation]] |oclc=818916200 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221121221030/https://reason.com/2022/11/21/the-qatar-world-cup-is-a-celebration-of-authoritarianism/ |archive-date=21 November 2022 |access-date=22 November 2022}}</ref><ref name="timesofindia">{{cite news |author=[[Reuters]] |date=16 November 2022 |title=FIFA World Cup 2022: Why Qatar is a controversial location for the tournament |url=https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/sports/football/fifa-world-cup-2022/fifa-world-cup-2022-why-is-qatar-a-controversial-location-for-the-tournament/articleshow/95533015.cms |work=Times of India |access-date=22 November 2022}}</ref> Some media outlets, sporting experts, and human rights groups have criticised Qatar's record of [[human rights violation]]s,<ref name="Atlantic 2022" /><ref name="Reason 2022" /><ref name="foreignpolicy">{{cite magazine |date=25 November 2022 |title=Qatar Can't Hide Its Abuses by Calling Criticism Racist |url=https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/11/25/qatar-cant-hide-its-abuses-by-calling-criticism-racist/ |url-status=live |magazine=[[Foreign Policy]] |location=[[Washington, D.C.]] |publisher=[[Graham Holdings Company]] |issn=0015-7228 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221127213633/https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/11/25/qatar-cant-hide-its-abuses-by-calling-criticism-racist/ |archive-date=27 November 2022 |access-date=28 November 2022 |author-last=Begum |author-first=Rothna}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author=Tony Manfred |date=1 March 2015 |title=14 reasons the Qatar World Cup is going to be a disaster |url=https://sports.yahoo.com/news/14-reasons-qatar-world-cup-174400894.html |access-date=2 March 2015 |publisher=[[Yahoo! Sports]]}}</ref> Qatar's limited football history, the high expected cost, the [[Climate of Qatar|local climate]],<ref name="Atlantic 2022"/> and [[bribery]] in the bidding process,<ref name="Reason 2022"/> though other parts of the world do not focus as much on these concerns.<ref>{{Cite news |date=2022-11-14 |title=2022 World Cup: Criticism of Qatar finds unequal resonance around the world |language=en |work=Le Monde.fr |url=https://www.lemonde.fr/en/sports/article/2022/11/14/2022-world-cup-criticism-of-qatar-finds-unequal-resonance-around-the-world_6004287_9.html |access-date=2022-11-21}}</ref> |

The awarding of the [[2022 FIFA World Cup]] to [[Qatar]] created a number of concerns and controversies regarding both Qatar's suitability as a host country and the fairness of the [[2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cup bids|FIFA World Cup bidding process]].<ref name="Atlantic 2022">{{cite magazine |author-last=McTague |author-first=Tom |date=19 November 2022 |title=The Qatar World Cup Exposes Soccer's Shame |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2022/11/qatar-hosting-fifa-world-cup-soccer/672171/ |url-status=live |magazine=[[The Atlantic]] |location=Washington, D.C. |publisher=[[Emerson Collective]] |issn=2151-9463 |oclc=936540106 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221119231915/https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2022/11/qatar-hosting-fifa-world-cup-soccer/672171/ |archive-date=19 November 2022 |access-date=20 November 2022}}</ref><ref name="Reason 2022">{{cite magazine |last=Boehm |first=Eric |date=21 November 2022 |title=The Qatar World Cup Is a Celebration of Authoritarianism |url=https://reason.com/2022/11/21/the-qatar-world-cup-is-a-celebration-of-authoritarianism/ |url-status=live |magazine=[[Reason (magazine)|Reason]] |publisher=[[Reason Foundation]] |oclc=818916200 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221121221030/https://reason.com/2022/11/21/the-qatar-world-cup-is-a-celebration-of-authoritarianism/ |archive-date=21 November 2022 |access-date=22 November 2022}}</ref><ref name="timesofindia">{{cite news |author=[[Reuters]] |date=16 November 2022 |title=FIFA World Cup 2022: Why Qatar is a controversial location for the tournament |url=https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/sports/football/fifa-world-cup-2022/fifa-world-cup-2022-why-is-qatar-a-controversial-location-for-the-tournament/articleshow/95533015.cms |work=Times of India |access-date=22 November 2022}}</ref> Some media outlets, sporting experts, and human rights groups have criticised Qatar's record of [[human rights violation]]s,<ref name="Atlantic 2022" /><ref name="Reason 2022" /><ref name="foreignpolicy">{{cite magazine |date=25 November 2022 |title=Qatar Can't Hide Its Abuses by Calling Criticism Racist |url=https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/11/25/qatar-cant-hide-its-abuses-by-calling-criticism-racist/ |url-status=live |magazine=[[Foreign Policy]] |location=[[Washington, D.C.]] |publisher=[[Graham Holdings Company]] |issn=0015-7228 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221127213633/https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/11/25/qatar-cant-hide-its-abuses-by-calling-criticism-racist/ |archive-date=27 November 2022 |access-date=28 November 2022 |author-last=Begum |author-first=Rothna}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author=Tony Manfred |date=1 March 2015 |title=14 reasons the Qatar World Cup is going to be a disaster |url=https://sports.yahoo.com/news/14-reasons-qatar-world-cup-174400894.html |access-date=2 March 2015 |publisher=[[Yahoo! Sports]]}}</ref> Qatar's limited football history, the high expected cost, the [[Climate of Qatar|local climate]],<ref name="Atlantic 2022"/> and [[bribery]] in the bidding process,<ref name="Reason 2022"/> though other parts of the world do not focus as much on these concerns.<ref>{{Cite news |date=2022-11-14 |title=2022 World Cup: Criticism of Qatar finds unequal resonance around the world |language=en |work=Le Monde.fr |url=https://www.lemonde.fr/en/sports/article/2022/11/14/2022-world-cup-criticism-of-qatar-finds-unequal-resonance-around-the-world_6004287_9.html |access-date=2022-11-21}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 23:15, 11 December 2022

It has been suggested that this article should be discuss ) (December 2022) |

| Part of a series on the |

| 2022 FIFA World Cup |

|---|

|

|

|

The awarding of the

Criticism of

Incumbent FIFA President

Human rights issues

Migrant workers, slavery allegations, and deaths

One of the most discussed issues of the Qatar World Cup was the treatment of workers hired to build the infrastructure.[1][2] Human Rights Watch and the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) state that the kafala system leaves migrants vulnerable to systematic abuse.[16][17] Workers could not change jobs or even leave the country without their sponsor's permission.[16] In November 2013, Amnesty International reported "serious exploitation", including workers having to sign false statements that they had received their wages in order to regain their passports.[18] Most Qatari nationals avoid doing manual work or low-skilled jobs. They are given preference in the workplace.[19] Michael van Praag, president of the Royal Dutch Football Association, requested the FIFA Executive Committee to pressure Qatar over those allegations to ensure better workers' conditions. He also stated that a new vote on the attribution of the World Cup to Qatar would have to take place if the corruption allegations were to be proved.[20]

The issue of migrant workers' rights attracted greater attention since the

After visiting a labour camp, Sharan Burrows of the ITUC stated that "If two years on [since the award of the 2022 World Cup] the [Qatari] Government has not done the fundamentals, they have no commitment to human rights".[16] The Qatar 2022 Committee said: "Our commitment is to change working conditions in order to ensure a lasting legacy of improved worker welfare. We are aware this cannot be done overnight. But the 2022 FIFA World Cup is acting as a catalyst for improvements in this regard."[16]

In September 2013, The Guardian reported that workers have faced poor conditions as companies handling construction for 2022 World Cup infrastructure forced workers to stay by denying them promised salaries and withholding necessary worker ID permits, rendering them illegal aliens. The report stated that there was evidence to suggest that workers face exploitation and abuse as defined by the International Labour Organization (ILO).[26] A video shown to labour rights group showed men living in dilapidated labour camps under unsanitary conditions.[27][28]

In May 2014, Qatar announced plans to abolish the Kafala system, but implementation was delayed until 2016,[29] and even if the promised reforms are implemented[needs update], employers would still have considerable power over workers (for example, a proposed requirement that wages must be paid into a designated bank account would not cover labourers paid in cash).[30][31]

In 2015, a crew of four journalists from the BBC were arrested and held for two days after they attempted to report on the condition of workers in the country.[32] The reporters had been invited to visit the country as guests of the Government of Qatar.[32] The Wall Street Journal reported in June 2015 the International Trade Union Confederation's claim that over 1,200 workers had died while working on infrastructure and real-estate projects related to the World Cup, and the Qatar Government's counter-claim that none had.[33] The BBC later reported that this often-cited figure of 1,200 workers having died in World Cup construction in Qatar between 2011 and 2013 is not correct, and that the 1,200 number is instead representing deaths from all Indians and Nepalese working in Qatar, not just of those workers involved in the preparation for the World Cup, and not just of construction workers.[25]

In March 2016, Amnesty International accused Qatar of using forced labour, forcing the employees to live in poor conditions, and withholding their wages and passports. It also accused FIFA of failing to act against the human right abuses. Migrant workers told Amnesty about verbal abuse and threats they received after complaining about not being paid for up to several months. Nepali workers were denied leave to visit their family after the 2015 Nepal earthquake.[34]

In October 2017, the ITUC said that Qatar had signed an agreement to improve the situation of more than two million migrant workers in the country. According to the ITUC, the agreement provided for substantial reforms in the labour system, including ending the Kafala system, and would positively affect the general situation of workers, especially those working on 2022 FIFA World Cup infrastructure projects. The workers would no longer need their employer's permission to leave the country or change their jobs.[35] In November 2017, the ILO started a three-year technical cooperation programme with Qatar to improve working conditions and labour rights. Qatar introduced new labour laws to protect migrant workers’ rights: Law No. 15 of 2017 introduced clauses on maximum working hours and constitutional rights to annual leave;[36] Law No. 13 of 2018 abolished exit visas for about 95 per cent of migrant workers.[37] On 30 April 2018, the ILO opened its first project office in Qatar to monitor and support the implementation of the new labour laws.[37][38]

In February 2019, Amnesty International said Qatar was falling short on promised labour reforms before the start of the World Cup, a sentiment that FIFA backed. Amnesty also found that abuses were still occurring.[39] In May 2019, an investigation by the UK's Daily Mirror newspaper discovered that some of the 28,000 workers on the stadiums were being paid 750 Qatari riyals per month, equivalent to £190 per month or 99 pence an hour for a typical 48-hour week.[40] In October 2019, the ILO said that Qatar had taken steps towards upholding the rights of migrant workers.[41]

In 2019, the Planning and Statistics Authority of the State of Qatar reported that 15,021 non-Qataris had died between 2010 and 2019 in its Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin - Births & Deaths 2019.[42]

In April 2020, the government of Qatar provided $824 million to pay the wages of migrant workers in quarantine or undergoing treatment for COVID-19.[43][44]

In August 2020, the Qatari government announced a monthly minimum wage for all workers of 1,000 riyals (US$275), an increase from the previous temporary minimum wage of 750 riyals a month.[45][46] The new laws went into effect in March 2021.[47] The ILO said "Qatar is the first country in the region to introduce a non-discriminatory minimum wage, which is a part of a series of historical reforms of the country's labour laws,"[48] but the campaign group Migrant Rights said the new minimum wage was too low to meet migrant workers' need with Qatar's high cost of living.[49] In addition, employers are obligated to pay 300 riyals for food and 500 riyals for accommodation, if they do not provide employees with these directly. The No Objection Certificate was removed so that employees can change jobs without consent of the current employer. A Minimum Wage Committee was also formed to check on the implementation.[50]

In February 2021, another investigative report published by The Guardian used data from embassies and national foreign employment offices to estimate a death toll of 6500 migrant workers since the World Cup was awarded to Qatar.[51] The figures used by The Guardian did not include occupation or place of work so deaths could not be definitively associated with the World Cup construction programme, but "a very significant proportion of the migrant workers who have died since 2011 were only in the country because Qatar won the right to host the World Cup."[51][52]

In March 2021, Hendriks Graszoden, the turf supplier for the 2006 World Cup and for the European Championships in 2008 and 2016, refused to supply Qatar with World Cup turf. According to company spokesperson Gerdien Vloet, one reason for this decision was the accusations of human rights abuses.[53]

In a September 2021 report, Amnesty criticised Qatar for failing to investigate migrant workers' deaths.[54]

In a December 2021 interview with

In February 2022, a Mexican economist working for the World Cup organising committee said she had to flee Qatar to avoid a possible jail sentence for extramarital sex after reporting being assaulted to Qatari authorities.[57] In April 2022, Qatar dropped criminal proceedings against the Mexican stadium worker. Human Rights Watch welcomed the decision to end the proceedings. The case against her was closed.[58]

At the March 2022 FIFA Congress in Doha, Lise Klaveness—head of the Norwegian Football Federation—criticised the organisation for having awarded the World Cup to Qatar, citing the various controversies surrounding the tournament. She argued that "in 2010 World Cups were awarded by FIFA in unacceptable ways with unacceptable consequences. Human rights, equality, democracy: the core interests of football were not in the starting XI until many years later. These basic rights were pressured onto the field as substitutes by outside voices. FIFA has addressed these issues but there's still a long way to go."[59][60] Hassan al-Thawadi, secretary general of Qatar 2022, criticised her remarks for ignoring the country's recent labour reforms.[60] In May 2022, Amnesty accused FIFA of looking the other way while thousands of migrants worked in conditions "amounting to forced labor", arguing that FIFA should have required labour protections as a condition of hosting.[61]

In August 2022, Qatari authorities arrested and deported over 60 migrant workers who protested about non-payment of wages by their employer, Al Bandary International Group, a major construction and hospitality firm. Some of the demonstrators, from Nepal, Bangladesh, India, Egypt and the Philippines, had not been paid for seven months. London-based labour rights body Equidem said most were sent home.[62] Qatar's labour ministry said it was paying Al Bandary workers and taking further action against the company - already under investigation for failing to pay wages.[63]

In September 2022, Amnesty published the results of a poll of over 17,000 football fans from 15 countries which showed 73% supported FIFA compensating migrant workers in Qatar for human rights violations.[64] FIFA responded with a statement noting progress on Qatar's migrant worker policies, adding "FIFA will continue its efforts to enable remediation for workers who may have been adversely impacted in relation to FIFA World Cup-related work in accordance with its Human Rights Policy and responsibilities under relevant international standards."[65]

On September 28, 2022, Danish sportswear company Hummel unveiled Denmark's "toned down" kits for the tournament in protest of Qatar's human rights record. One of these kits includes a black alternate kit that represents "the color of mourning", which references the dispute between Hummel and World Cup organisers in Qatar in which Hummel claimed that thousands of migrant workers died during the construction of the venues.[66] Hummel said in their statement on their official Instagram:

With the Danish national team's new jerseys, we wanted to send a dual message. They are not only inspired by Euro 92, paying tribute to Denmark's greatest football success, but also a protest against Qatar and its human rights record. That's why we've toned down all the details for Denmark's new World Cup jerseys, including our logo and iconic chevrons. We don't wish to be visible during a tournament that has cost thousands of people their lives. We support the Danish national team all the way, but that isn't the same as supporting Qatar as a host nation. We believe that sport should bring people together. And when it doesn't, we want to make a statement.[67]

On 24 November 2022, during the tournament, the European Parliament adopted a resolution requesting FIFA to help compensate the families of migrant workers who died in Qatar, and for Qatar conduct a full human rights investigation.[68]

Women's rights

Discrimination against women was also criticized.[69][70] Women in Qatar must obtain permission from their male guardians to marry, study abroad on government scholarships, work in many government jobs, travel abroad, receive certain forms of reproductive health care, and act as the primary guardian of children, even if they are divorced.[71]

A Mexican employee of the World Cup Organizing Committee was accused of allegedly having sex outside of marriage. The woman had previously reported rape. However, the male claimed to have been in a relationship with her, after which the woman was investigated for extramarital sex. Women in Qatar face the possible penalty of flagellation and a seven-year prison sentence if convicted for having sex outside of marriage. The criminal case against the Organizing Committee employee was dropped months after she was allowed to leave Qatar.[72]

LGBT issues

LGBT fans

The

On several occasions the Qatari organisers have promised to comply with FIFA rules on promoting tolerance, including LGBT issues. On 8 December 2020, Qatar announced that rainbow flags will be allowed in stadiums at the 2022 World Cup. Nasser Al-Khater, 2022 World Cup chief executive, said: "When it comes to the rainbow flags in the stadiums, FIFA have their own guidelines, they have their rules and regulations, whatever they may be, we will respect them."[81] On 21 September 2022, Football Association (England) chief executive Mark Bullingham said there had been assurances that LGBT couples would not face arrest while holding hands or kissing in public in Qatar.[82]

Shortly before the tournament commenced, former Qatar international player and World Cup ambassador Khalid Salman described homosexuality as a "damage in the mind" in an interview with German broadcaster ZDF, which led to further criticism, including from the German government. The interview was cut short following the comments.[83][84]

Team apparel

Several European captains – those of England, Wales, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Switzerland and the Netherlands – were planning to wear

The United Kingdom (for England and Wales) and United States governments also criticised FIFA for introducing player punishment for the armbands.[88][89] British newspaper Metro changed its website logo to a rainbow to protest the FIFA decision.[90] Also on 21 November, FIFA rejected Belgium's away jerseys due to the word "Love" being on the inside of the collar, even though it was unrelated to any campaign supporting LGBT rights.[91][92][93] The United States included a rainbow in their team branding, replacing the red stripes in their logo with differently coloured ones to create a Pride rainbow, but only used this for facilities used by the team, not on their jerseys.[94]

On 22 November, the German Football Association (DFB) announced that they were taking legal action against FIFA for the decision, submitting a case to the Court of Arbitration for Sport.[95] The German team played their first match the next day, and covered their mouths with their hands during their team photo as a protest against FIFA, signalling that they had been silenced.[96] The Football Association (FA), England football's governing body, also announced they were exploring legal options, saying that it understands World Cup rules would only administer a fine for kit violations and that FIFA may be attempting to enforce IFAB rules, which could allow them to implement other sanctions and which England believe should not apply to the World Cup, instead.[97]

On 23 November, the

Also on 23 November, Irish foreign minister Simon Coveney criticised the world football governing body in his country's parliament, describing it as "absolutely extraordinary that FIFA has effectively chosen to lean on national football associations in different countries to prevent players wearing an armband to support LGBT+ rights". He also said: "That is a political intervention by FIFA to limit freedom of expression, which is worthy of significant mention and criticism."[101]

Fans began buying OneLove armbands after the ban and according to Badge Direct, who produce the armbands, they were sold out by 24 November.[102] In response, FIFA allowed teams to wear the official "no discrimination" armbands intended for the quarter-finals during the group stage.[103]

Other attendees' apparel

US journalist Grant Wahl was detained for half an hour, before the United States' opener against Wales. He was wearing a black shirt with a rainbow on the front. He was told his shirt was not allowed due to it being "political". After 25 minutes, a security commander allowed him into the venue and apologised, and he also received an apology from a representative of FIFA. He later passed away on December 10th under mysterious circumstances after collapsing towards the end of the quarter-final match between Argentina and the Netherlands.[104][105]

Female Wales fans and Football Association of Wales (FAW) staff (including former Wales women's football captain Laura McAllister) had rainbow bucket hats, produced by the FAW, confiscated at the same game.[106] The FAW said they were "extremely disappointed" and they would be raising the incidents with FIFA the following day;[107] FIFA subsequently opened talks about rainbow apparel with Qatari officials on 22 November.[108]

A Brazilian journalist had his phone seized by authorities when people mistook a flag representing his state, Pernambuco's, flag, which includes a rainbow within a larger design, for an LGBT flag. Other Brazilian fans from the region reported similar incidents of having flags taken from them because of the rainbow.[109]

According to BBC reporter Natalie Perks, she and a cameraman were prevented from entering Al Bayt Stadium ahead of the England vs United States Group B game on 25 November because the cameraman was found to have a rainbow-decorated watch and strap in his possession, which had been gifted to him by his son. Perks said they were eventually permitted entry to the stadium after dialling a number aimed specifically at media personnel to help them if they encountered difficulties.[110] According to The Guardian, a reporter for The Times newspaper was questioned at the same stadium around the same game because of a wristband they were wearing.[111]

Despite FIFA reassuring fans that rainbow coloured apparels would be allowed inside the stadium, Qatari officials continued to confiscate rainbow-coloured items from several fans.[112][113]

One fan attending a Group A final round game involving the Dutch national team on 29 November had a security guard scream in his face, was forced to take off a multi-coloured baseball cap he was wearing and then was forced to strip his clothes, including his underwear. Then his cap disappeared and security staff claimed he wasn't wearing it at all, only for it to emerge from behind a scanner. Then, when his ticket was being checked he was told to stand in the corner, where he was surrounded by seven people, four of whom were police and one of whom was wearing a FIFA uniform, where further threats were made.[114]

Homophobic football chants

A perennial issue in the sport in some countries, homophobic football chants were reported to be heard at the first matches involving Mexico and Ecuador, particularly from Ecuador fans towards Chile[115] and the Qatar team during the tournament's opening match, with FIFA opening hearings to determine disciplinary action.[116] Mexico was subject of a second disciplinary measure by FIFA after the final group stage match against Saudi Arabia because of homophobic chants during the course of the game.[117]

Pre-tournament

Stadiums

Involvement of Albert Speer

Albert Speer (Jr), son of Hitler's chief architect and Minister of Armaments and War Production Albert Speer (Sr), was given the responsibility of designing the stadiums for the 2022 Qatar World Cup. Barney Ronay, a senior sportswriter with The Guardian, expressed disbelief that the Qatar Supreme Committee thought it "the best vibe, the best shout" to involve an architect who is reminiscent of the Nazis.[118]

According to Der Spiegel, "Speer's stadium designs are a significant reason why Qatar was awarded the 2022 football World Cup."[119]

Environmental impact

Each stadium in Qatar requires 10,000 litres of water per day in winter months, when the tournament is taking place, to maintain the pitch. With little access to freshwater in the nation, the sourced water was saltwater, which has to be desalinated. The process damages the marine environment. Desalination plants in the Middle East also heavily rely on the use of fossil fuels. As well as the pitches at the stadiums, the organising committee grew and maintained a large farm of match-suitable fresh grass outside Doha, in case of turf damage. The need for so much desalination, and the oil and gas used to power the plants, have been criticised.[120]

One of the eight stadiums,

Corruption

There have been allegations of bribery or corruption in the Qatar's 2022 World Cup selection process involving members of FIFA's executive committee. There have been numerous allegations of bribery between the Qatar bid committee and FIFA members and executives, some of whom—including Theo Zwanziger and Sepp Blatter—were later recorded regretting awarding Qatar the tournament.[122][123][124][125]

2011

In May 2011, allegations of corruption within the FIFA senior officials raised questions over the legitimacy of the World Cup being held in Qatar. According to then vice-president Jack Warner, an email has been publicised about the possibility that Qatar 'bought' the 2022 World Cup through bribery via Mohammed bin Hammam who was president of the Asian Football Confederation at the time. Qatar's officials in the bid team for 2022 have denied any wrongdoing.[126] A whistleblower, revealed to be Phaedra Almajid, alleged that several African officials were paid $1.5m by Qatar.[127] She later retracted her claims of bribery, stating she had fabricated them in order to exact revenge on the Qatari bid team for relieving her of her job with them. She also denied being put under any pressure to make her retraction. FIFA confirmed receiving an email from her which stated her retraction.[128][129]

2014–15

In March 2014, it was alleged that a firm linked to Qatar's successful campaign paid committee member

On 1 June 2014, The Sunday Times claimed to have obtained documents including e-mails, letters and bank transfers which allegedly proved that Bin Hammam had paid more than 5 million US dollars to Football officials to support the Qatar bid. Bin Hamman and all those accused of accepting bribes denied the charges.[131]

Later in June 2014,

In an interview published on 7 June 2015,

FIFA ethics investigation report

In 2014, FIFA appointed Michael Garcia as its independent ethics investigator to look into bribery allegations against Qatar and Russia, the hosts for the 2018 and 2022 World Cup. Garcia investigated all nine bids and eleven countries involved in the 2018 and 2022 bids and spoke to all persons connected to the bids and appealed for witnesses to come forward with evidence.[135] At the end of investigation, Garcia submitted a 430-page report in September 2015. FIFA governing body then appointed a German judge Hans Joachim Eckert who reviewed and presented a 42-page summary of the report two months later. The report cleared Qatar and Russia of bribery allegations stating that Qatar "pulled Aspire into the orbit of the bid in significant ways" but did not "compromise the integrity" of the overall bid process.[136]

Michael Garcia reacted almost immediately stating that the report is “materially incomplete” and with “erroneous representations of the facts and conclusions".[136] In 2017, a German journalist Peter Rossberg who claimed to have obtained the report wrote in a Facebook post that the report "does not provide the proof that the 2018 or 2022 World Cup was bought" and stated that he would publish the full report bit by bit. This forced FIFA to release the original report as authored by the investigator Michael Garcia. The full report did not provide any evidence of corruption against the host of 2022 World Cup but stated that bidders tested rules of conduct to the limit.[137] The report ended talks of a re-vote.

2020

In January,

According to leaked documents obtained by The Sunday Times, Qatari state-run television channel Al Jazeera secretly offered $400 million to FIFA, for broadcasting rights, just 21 days before FIFA announced that Qatar will hold the 2022 World Cup. The contract also documented a secret TV deal between FIFA and Qatar's state run media broadcast Al Jazeera that $100 million will also be paid into a designated FIFA account only if Qatar wins the World Cup ballot in 2010. An additional $480 million was also offered by the State of Qatar government, three years after the initial offer, which brings the amount to $880 million offered by Qatar to host the 2022 World Cup. The documents are now part of the bribery inquiry by Swiss Police.[139][140]

FIFA refused to comment on the inquiry and responded to The Sunday Times in an email and wrote "allegations linked to the FIFA World Cup 2022 bid have already been extensively commented by FIFA, who in June 2017 published the Garcia report in full on Fifa.com. Furthermore, please note that Fifa lodged a criminal complaint with the Office of the Attorney General of Switzerland, which is still pending. FIFA is and will continue to cooperate with the authorities."[138][139] A beIN spokesman said in a statement that the company would not "respond to unsubstantiated or wildly speculative allegations."[141]

Damian Collins, a British Member of Parliament (MP) and chairman of a UK parliamentary committee, called for payments from Al Jazeera to be frozen and launched an investigation into the apparent contract since the contract "appears to be in clear breach of the rules".[138]

Former UEFA president

Scheduling

The notion of staging the tournament in winter proved controversial; Blatter ruled out a January or February event because it may clash with the 2022 Winter Olympics,[144] while others expressed concerns over a November or December event, because it might clash with the Christmas season (even though Qatar is predominantly Muslim, the players in the tournament are predominantly Christian).[145] The Premier League voiced concern over moving the tournament to the northern hemisphere's winter as it could interfere with the local leagues. FA Chairman Greg Dyke said, shortly after he took his job in 2013, that he was open to either a winter tournament or moving the tournament to another country.[146] FIFA executive committee member Theo Zwanziger said that awarding the 2022 World Cup to Qatar's desert state was a "blatant mistake", and that any potential shift to a winter event would be unmanageable due to the effect on major European domestic leagues.[122]

In October 2013, a taskforce was commissioned to consider alternative dates, and report after the 2014 World Cup in Brazil.

It was agreed all the stakeholders should meet, all the stakeholders should have an input and then the decision would be made, and that decision as far as I understand will not be taken until the end of 2014 or the March executive meeting in 2015. As it stands it remains in the summer with no decision expected until end of 2014 or March 2015".[148] Another option to combat heat problems was changing the date of the World Cup to the northern hemisphere's winter, when the climate in Qatar would be cooler. However, this proved just as problematic as doing so would disrupt the calendar of a number of domestic leagues, particularly in Europe.[122]

Franz Beckenbauer, a member of FIFA's executive committee, said Qatar could be allowed to host the 2022 World Cup in winter. He justified his proposal on the grounds that Qatar would be saving money, which otherwise they would have spent in cooling the stadiums. Beckenbauer said: "One should think about another solution. In January and February you have comfortable 25 °C (77 °F) there". "Qatar won the vote and deserves a fair chance as the first host from the Middle East".[149] At a ceremony in Qatar marking the occasion of having been awarded the World Cup, FIFA President Sepp Blatter later agreed that this suggestion was plausible,[150] but FIFA later clarified that any change from the bid position of a June–July games would be for the host association to propose.[151] Beckenbauer would later receive a 90-day ban from any football-related activity from FIFA after refusing to cooperate in the investigation of bribery.[152]

The notion of holding the Cup during Europe's winter was further boosted by UEFA President Michel Platini's indicating that he was ready to rearrange the European club competitions accordingly. Platini's vote for the summer 2022 World Cup went to Qatar.[153] FIFA President Sepp Blatter also said that despite air-conditioned stadiums the event was more than the games itself and involved other cultural events. In this regard, he questioned if fans and players could take part in the summer temperatures.[154]

In addition to objections by European leagues,

In September 2013, it was alleged that FIFA had held talks with broadcasters over the decision to change the date of the World Cup as it doing so could cause potential clashes with other scheduled television programming. The

In February 2015, FIFA awarded Fox the rights to the 2026 World Cup, without opening it up for bidding with ESPN, NBC, and other interested American broadcasters.[158] Richard Sandomir of The New York Times reported that FIFA did so to avoid Fox from suing in U.S. courts, which under the American legal system could force FIFA to open up their books and expose any possible corruption.[159] As BBC sports editor Dan Roan observed, "It does not seem to matter to FIFA that rival networks ESPN and NBC may have wanted to bid, or that more money could have been generated for the good of the sport had a proper auction been held. As ever, it seemed, FIFA was looking after itself".[160]

On 24 February 2015, it was announced that a winter World Cup would go ahead in favour of the traditional summertime event. The event was scheduled to be held between November and December. Commentators noted the clash with the Christmas season was likely to cause disruption, whilst there was concern for how short the tournament was intended to be. It was also confirmed that the 2023 Africa Cup of Nations would be moved from January to June to prevent African players from having a relatively quick two-week turnaround, although the monsoonal rainy season in its host country Guinea starts about that time.[161]

Climate

As the World Cup usually occurs during the northern hemisphere's summer, the weather in Qatar was a concern with temperatures reaching more than 50 °C (122 °F). Two doctors from Qatar's Aspetar sports hospital in Doha who gave an interview in November 2010 to Qatar Today magazine said the climate would be an issue, stating that the region's climate would "affect performance levels from a health point of view" of professional athletes, specifically footballers, that "recovery times between games would be longer" than in a temperate climate and that, on the field of play, "more mistakes would be made". One of the doctors said that "total acclimation (to the Qatari climate) is impossible".[162]

The inspection team for evaluating who would host the tournament said that Qatar was "high risk" due to the weather. FIFA President Sepp Blatter initially rejected the criticism, but in September 2013 said the FIFA executive committee would evaluate the feasibility of a winter event instead of a summer one.

Cost

By some estimates, the World Cup is set to cost Qatar approximately US$220 billion (£184 billion). This is about 60 times the $3.5 billion that South Africa spent on the 2010 FIFA World Cup.[163] Nicola Ritter, a German legal and financial analyst, told an investors' summit held in Munich that £107 billion would be spent on stadiums and facilities plus a further £31 billion on transport infrastructure. Ritter said £30 billion would be spent on building air-conditioned stadiums with £48 billion on training facilities and accommodation for players and fans. A further £28 billion will be spent on creating a new city called Lusail that will surround the stadium that will host the opening and final matches of the tournament.[164]

According to a report released in April 2013 by

Possible Israeli qualification

The head of the Qatar bid delegation stated that if Israel were to qualify, they would be able to compete in the World Cup despite Qatar not recognising the state of Israel.[169][170][171] Israel ultimately were eliminated during FIFA World Cup qualification, and thus did not compete at the tournament in Qatar.

Russian participation after its invasion of Ukraine

After the Russian Federation's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, FIFA stated that matches would not be held in Russia, though Russia would still be able to continue its participation in World Cup qualifying, where it had reached Path B. Also in Path B were Poland, the Czech Republic and Sweden, all of which refused to play against Russia in any form (as did England, which had already qualified for the tournament).[172]

On 27 February 2022, FIFA announced a number of sanctions impacting Russia's participation in international football. Russia was prohibited from hosting international competitions, and the national team had been ordered to play all home matches behind closed doors in neutral countries. They may not compete under the name, flag, or national anthem of Russia: similarly to the Russian athletes' participation in events such as the Olympics,[173] the team would compete under the abbreviation of their national federation, the Russian Football Union ("RFU") rather than "Russia".[174] The next day, FIFA decided to suspend Russia from international competitions "until further notice", including its participation in the 2022 FIFA World Cup.[175] In July 2022, the Court of Arbitration for Sport dismissed the Russian appeals and upheld FIFA's and UEFA's decisions.[176]

Some observers, while approving of the boycott of Russia, pointed out that FIFA did not boycott Saudi Arabia for its

Qatari football record

At the time of being awarded the tournament in 2010, Qatar was ranked 113 in the world,[180] and had never qualified for the World Cup before. The most prestigious accolade the team had won was the Arabian Gulf Cup twice, both times hosting. Since being awarded the tournament, they have also won the Arabian Gulf Cup for a third time in 2014 and the AFC Asian Cup in 2019. Qatar became the smallest country by land area to host the World Cup (less than half the size of 1954 hosts Switzerland). These facts led some to question the strength of football culture in Qatar and if that made them unsuitable World Cup hosts.

The

With a 2–0 loss to Ecuador on the tournament's opening day, Qatar became the first host nation to lose their opening match at the World Cup;[186] Qatar subsequently lost 3–1 to Senegal in their second group match, becoming the first team to be eliminated from the tournament.[187] They lost their final group game 2–0 to the Netherlands, becoming the first and only host to lose all their games.[188]

Alcohol

Hassan Abdulla al Thawadi, chief executive of the Qatar 2022 World Cup bid, said the

In February 2022, the communications executive director at the supreme committee, Fatma Al-Nuaimi, stated in an interview that alcohol would be available in designated fan zones outside stadiums and in other Qatari official hospitality venues.[193] In July 2022, it was reported that while fans would be allowed to bring alcoholic beverages into the stadiums, alcoholic beverages would not be sold inside the stadiums. But according to a source, "the plans are still being finalised."[194] However, on 18 November 2022, days before the first match, Qatar officially banned alcoholic beverages from sale within the eight stadiums.[195]

On 30 November 2022, The Times published an interview with some female fans attending FIFA World Cup 2022 games, with some of them saying that less drunkenness among other attendees made them feel safer at the stadiums than they expected.[196]

November 2022 Infantino communications

"Focus on the football" letter

On 5 November 2022,

"Today I feel" address

On 19 November 2022, Infantino gave an hour-long address to the media during a pre-tournament press conference, during which he defended FIFA's hosting of the tournament in Qatar, and commented upon pre-tournament developments such as the banning of alcohol.[198] He opened by declaring that he "felt" Qatari, Arabic, African, gay, disabled, and like a migrant worker, because he understood how it felt to be discriminated.[198] He argued that criticism of the treatment of migrant workers by Western critics was hypocritical because "for what we Europeans have been doing for 3,000 years around the world, we should be apologising for the next 3,000 years before starting to give moral lessons to people". Infantino argued that none of the European companies "who earn millions and millions from Qatar or other countries in the region" had taken steps to address the rights of migrant workers like FIFA had, and suggested that Europe needed to be more open to accepting refugees and migrant workers.[199][14] He asked, "do we want to continue to spit on the others because they look different, or they feel different? We defend human rights. We do it our way. We obtain results. We got women fans in Iran. The Women's League was created in Sudan. Let’s celebrate. Don't divide."[198][199][14] In response to a last-minute prohibition on the sale of alcohol inside the stadiums, Infantino stated that it was a decision made jointly by FIFA and the organising committee, but argued that FIFA was still in "200% control" of the event, prohibitions on the sale of alcohol at sporting events were not exclusive to Qatar, and joked that "if this is the biggest issue we have for the World Cup then I will resign immediately and go to the beach to relax".[199][14] He once again argued that people should "focus on the football", and direct their criticism to FIFA and "me if you want" instead of Qatar.[200]

The speech draw further criticism: The Associated Press labeled the speech an "extraordinary diatribe" and a "tirade"[201] while The Guardian called it "bizarre and incendiary".[198] Infantino was accused of deflecting criticism of Qatar's human rights record.[199][14] Amnesty International criticised Infantino for "brushing aside legitimate human rights criticisms",[198] Sky Sports pundit Melissa Reddy accused Infantino of engaging in whataboutism,[200] while FairSquare director Nicholas McGeehan described the remarks as being "as crass as they were clumsy", and feeling like "talking points directly from the Qatari authorities".[198] Writing for The Observer, Barney Ronay described the address as being "a wretched spectacle—not to mention myopic, tin-eared and oddly lost", and felt that Infantino was "clearly furious with his critics, furious that this thing cannot be bent to his will. And by the end it had become hugely engrossing just to see someone so blind to his own contortions, so shameless, and quite clearly losing his grip on his own spectacular."[202]

Opening ceremony and anthem

In the weeks before the tournament began, singers Dua Lipa and Shakira announced that they had refused to perform at the opening ceremony and collaborate on the tournament anthem due to human rights violations implemented by the Emirate's internal policies.[203] British singer Rod Stewart said he turned down a substantial offer to perform in the country: "They offered me a lot of money, more than a million dollars, to perform there [in Qatar]. I turned it down. It's not right to go there."[204] In addition, the league's ambassador, David Beckham, was criticized by the LGBT community in the United Kingdom for lending his face to the event in exchange for $10 million. Talking about the fact former Spice Girls member Melanie C, arguing that it is "complex" for sports to change culture when so much money is involved.[205] British singer Robbie Williams defended his choice to participate as a guest at the opening event, stating: "I don't condone any abuses of human rights anywhere. But, that being said, if we're not condoning human rights abuses anywhere, then it would be the shortest tour the world has ever known. [...] You get this microscope that goes 'okay, these are the baddies, and we need to rally against them'... I think that the hypocrisy there is that if we take that case in this place, we need to apply that unilaterally to the world. Then if we apply that unilaterally to the world, nobody can go anywhere".[206][207]

After the announcement of the collaboration for the World Cup anthem "

American actor Morgan Freeman was criticised on social media by media outlets for participating in the tournament's opening ceremony, with references made to his acting performance as Nelson Mandela in the dedicated film Invictus (2009).[213][214] During Freeman's monologue, numerous spectators left the stadium in protest.[215]

Iranian protests

In October 2022, calls were made to ban the

Since the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the presence of Iranian women in Iranian stadiums had been illegal until October 2019 after the death of Sahar Khodayari, when select Iranian women were allowed to enter the stadium after 40 years for a World Cup qualifier.[219] However, in March 2022, Iranian women were again banned from entering the stadium for a World Cup qualifier, with authorities using pepper spray to disperse them.[220]

Former Iranian national team goalkeeper

In early November 2022, the

Ahead of the country's opening game (Group B England vs Iran match), many Iranians boycotted their team as they felt it was representing the government.[223] Ahead of that opening game against England, the Iranian team refused to sing the national anthem in solidarity with the Mahsa Amini protests, with some Iranian supporters cheering against their own team or boycotting their team as a result.[224][225][226][227]

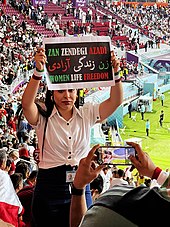

In the following match against Wales, amidst the boos and whistles from the Iranian supporters during the playing of the national anthem, the Iranian players were filmed singing the national anthem, with some protestors having their pre-revolutionary Lion and Sun flags and Women, Life, Freedom banners snatched from them by pro-government fans and stadium security at the Ahmad bin Ali Stadium.[228][229][230][231] Security guards at the Ahmad bin Ali Stadium seized a flag with the inscription "Woman. Freedom. Life" from an Iranian fan before the Group B game between Iran and Wales.[232] Reuters reported on several incidents involving Iranian fans at this game, including a man wearing a shirt emblazoned with the words "Women, Life, Freedom" being escorted by three security officers into the ground, but was unable to confirm why he was being given a security escort,[233] as well as a Reuters photograph which showed a woman whose face was painted with dark red tears holding a shirt in the air with "Mahsa Amini - 22" on it.[233] Another Iranian fan told Reuters that her friends had been prevented from entering the stadium due to their effforts to bring t-shirts reading "Women Life Freedom" but that she had managed to get one t-shirt through the security blanket outside the stadium.[233] Protesters were harassed by government supporters with some protesters being detained by Qatari police, while stadium security confirmed they were given orders to confiscate anything but the flag of the Islamic Republic of Iran.[234][235] Protesters against the regime covered the lenses of security cameras with sanitary pads.[236] One Iranian fan said Qatari police insisted she wash away the markings on her arms and chest, which commemorated those who had been killed by Iranian security forces.[228] Documents obtained by Iran International showed Iran was coordinating secret efforts with Qatar to control who attends the World Cup and restrict any signs of dissent.[237]

Prior to what would be Iran's final fixture (Group B Iran vs United States match), Iran's state-run media called for the US team to be expelled from the tournament after the US Soccer Federation removed the Islamic Republic emblem from Iran's flag in a social media post. The US Federation confirmed it had done so to show support for Iranian protesters before deleting the post. FIFA did not comment on the issue.[238]

Ahead of that concluding fixture against the United States, the Iranian players were reportedly called in to a meeting with members of the IRGC and threatened with violence and the torture of their families if they did not sing the national anthem or joined the protests against the Iranian regime.[239] During the match, the Iranian players sang the national anthem again before losing to the United States 1–0 for the first time in their history, thereby being knocked out of the tournament.[240] Many Iranians celebrated the defeat and one Iranian man was killed by security forces in Bandar-e Anzali after honking his car horn in celebration.[241] Another Iranian fan was arrested by Qatari police after he was wearing a shirt with the Woman, Life, Freedom slogan.[242]

Treatment of fans

Jewish and Israeli fans

It was reported that Qatar went back on its word to provide cooked

Multiple Israeli reporters at the tournament reported fans from Arab nations chanting anti-Israeli slogans.[244][245] Some Israelis reported that they had been escorted out of restaurants when their nationality was revealed.[246]

Paid fans

In 2020, Qatar began a fan engagement program promising to pay air travel, entrance tickets to matches, housing and even spending money for groups of fans from all competing nations. However, fans who are handpicked by the Qatari government are required to sing and chant when asked to, and are required to report any social media posts which are critical of Qatar. Many fans reportedly declined the offer.[247] On 18 November 2022, it was reported that Qatar had cancelled the daily spending allowances for fans who were paid to attend the World Cup.[248]

Days prior to the start of the 2022 FIFA World Cup, Qatar was accused of reportedly having paid actors to play the role of fans at the tournament in order to promote the country.[249][250][251][252][253] Qatar was similarly accused of having paid for supporters when it hosted the 2015 World Men's Handball Championship.[254]

During the World Cup, Nejmeh SC ultras from Lebanon were employed by the Qatari government to act as Qatar national team fans during their games. The 1,500 "adopted" ultras wore maroon t-shirts with "Qatar" stamped on front, sang the Qatari national anthem and beat drums while singing chants.[255]

Accommodation

In the days leading up to the tournament, videos emerged of the tournament accommodation, which consisted of shipping containers, some with a curtain leading to the exterior instead of four solid walls, and portable air conditioners. This accommodation cost over $200 a night. A Greek salad which costs $10, consisting of a small amount of lettuce, one slice of cucumber, and no feta, served in a foam container was criticized as expensive and unpalatable. These criticisms led to comparisons to the ill-fated Fyre Festival.[256] Alcohol, where available, is expensive, with beer being $13.73 for 500ml.[257]

One official fan village, comprising hundreds of shipping containers, still resembled a building site less than two days before the first World Cup match. People who had stayed in another village complained about the air conditioning and beds: "It has been hell. The air con in the cabin barely works and sounds like a [fighter jet] is taking off.... [The beds] are rock hard so you might as well sleep on the floor."[258]

Due to these issues, which Qatar officials say were caused by "owner and operator negligence", Qatar offered refunds to fans "severely impacted" by the issues.[259]

Provisions inside stadiums

Qatar bid's chief executive, Hassan al-Thawadi said "Heat is not and will not be an issue".[260] Journalist John Smallwood of the Daily News said the Qatar 2022 bid's official site explains:

Each of the five stadiums will harness the power of the sun's rays to provide a cool environment for players and fans by converting solar energy into electricity that will then be used to cool both fans and players at the stadiums. When games are not taking place, the solar installations at the stadiums will export energy onto the power grid. During matches, the stadiums will draw energy from the grid. This is the basis for the stadiums’

carbon neutrality. Along with the stadiums, we plan to make the cooling technologies we’ve developed available to other countries in hot climates, so that they too can host major sporting events.[261]

Keepie uppie challenge

One self-described "overweight" fan, who had set a target of doing keepie uppies outside each of the eight stadiums at which matches in the tournament were played, was "set upon" by four officials who surrounded him from contrasting directions outside Al Bayt Stadium. The fan said: "I was a bit worried as it's daunting being in a foreign country and then being set upon by four security guards, pinning you in". The officials demanded he delete the video he had been filming, which was part of a "light-hearted" attempt to distract his YouTube audience from the "doom and gloom" of world events. While playing keepy-uppy near Stadium 974, Qatari officials twice drove him to a train station after pursuing him in a golf buggy.[262]

Brass band instrument confiscation

Though not connected to any protest against Iran, the official Wales brass band had their instruments confiscated before the Group B Wales vs Iran match. The brass band had been allowed to play at the previous Wales match (against the United States) and FIFA officially supported their attendance at the tournament.[263]

Security

A woman journalist from Argentina, Dominique Metzger was robbed of items from her handbag during live reporting. When she approached the police, they asked her "What justice do you want? What sentence do you want us to give him? Do you want him to be sentenced to five years in prison? Do you want him to be deported?"[264]

Ticketing

Many England supporters missed the start of the Group B England vs Iran match due to problems with FIFA's ticketing app.[265] That day also, the FIFA app caused tickets belonging to fans of the United States team to disappear.[266][267]

There were problems also with ticketing, first before, and then during, throughout, the Round of 16 Morocco vs Spain match on 6 December, including with FIFA's ticketing app.[268][269][270][271]

Attendances

Match attendance figures came under scrutiny due to reported crowd attendances that exceeded stadium capacities, this despite games having visibly empty seats.[13]

Media incidents

Security interference

Prior to the tournament, there were several reported incidents of altercations between broadcasters and Qatari security officials. Rasmus Tantholdt of Denmark's

RTÉ journalist Tony O'Donoghue accused Qatari police of stopping him during efforts to film in the country on 17 November.[274]

Dominique Metzger, a reporter from Argentina, had a wallet and important documents stolen from a bag during a live TV broadcast.[275]

With the tournament underway, television presenter Joaquín 'El Pollo' Alvarez (from Argentina) was interrupted by Qatari forces when he was in the middle of a live television broadcast outdoors in Barwa Village, a complex in Doha designed specifically for Qatar's hosting of the tournament. Alvarez was interviewing an older supporter who was sitting in her wheelchair. He had to stop when asked if he was an accredited media representative and, with the help of a colleague, search for a press pass in his bag. But then an official became irritated and ordered the cameraman to stop filming, insisting that the outdoor street was "private". Alvarez said he had been threatened with arrest ("I was frightened and thought they were going to take me prisoner... It's impossible to work and enjoy a World Cup like this"). The film crew were threatened also with the destruction of their equipment. Nicolas Magali, who was co-hosting the live broadcast from the TV studio in Argentina's capital Buenos Aires, told viewers: "This is an example of severe censorship and we have to say so. They covered up the camera, didn't let us film, ordered you away in a rude fashion and on top of that the person doing the talking didn't identify himself".[276][277]

Death of Grant Wahl

American soccer journalist Grant Wahl collapsed and died while covering the Netherlands vs. Argentina match in the early morning of 10 December 2022.[278]

Wahl had experienced cold-like symptoms in the days prior, but felt better following a course of treatment from the World Cup medical centre.[278] An outspoken critic of Qatar's selection as World Cup host, Wahl had been briefly detained while wearing a t-shirt depicting a rainbow at an earlier game during the tournament (United States vs Wales).[279] Wahl reportedly received death threats for wearing the shirt, and his brother said he believes Wahl's death was the result of foul play, implicating the Qatari government as playing a role.[280][281]

Other journalists with Wahl at the time of his death have reported that he did not collapse but instead began fitting or experiencing a seizure, and called for help himself. They have criticised the Qatar Supreme Committee for not providing

Chinese censorship

CCTV, the state broadcaster and the official broadcaster of FIFA World Cup in mainland China, replaced footage of maskless audiences with close-ups of coaches, officials or players, or birds-eye view of stadiums in its broadcast, as scenes of maskless audiences fueled unrest with China's zero-COVID policy during ongoing protests.[283] Following the protests, the Chinese government began to relax pandemic control measures and more images of audience without masks appeared on live telecast.[284]

Algerian censorship

After the Group F Belgium vs Morocco match, state-run TV2 of Algeria completely omitted the existence of the Morocco match, due to tensions between Algeria and Morocco.[285] After Morocco defeated Spain in the Round of 16, Algeria's state TV channel and the Algeria Press Service never mentioned Morocco's victory, although many Algerians celebrated for Morocco.[286]

Boycotts

Tromsø IL of Norway released a statement calling for a boycott of the 2022 World Cup, in relation to reports of "modern-day slavery" and the "alarming number of deaths", among additional concerns in their statement. The club urged the Norwegian Football Federation to support such a boycott.[287]

In reaction to the

On 20 June 2021, a congress of the Norwegian Football Federation decided against a boycott of the 2022 World Cup in Qatar.[293]

On 20 October 2021, the German Football Association (DFB) published an interview on its website that confirmed that Germany would not boycott the 2022 World Cup in Qatar. According to vice-president Peter Peters, "Qatar has seen many positive developments in the past few years, and it is football's role to support those developments."[294][291]

On 27 March 2022, the Fourth High-Level Strategic Dialogue between the State of Qatar and the

In November 2022, fans of Borussia Dortmund, Bayern Munich, and Hertha Berlin unveiled banners calling for a boycott of the Qatar World Cup.[296][297]

In October 2022, it was announced Paris had joined other French cities in boycotting the broadcasting of the 2022 tournament amid concerns over rights violations of migrant workers and the environmental impact of the tournament.[298][299][300]

Cologne-based supermarket chain REWE cut all ties with the German Football Association (DFB) with immediate effect on 23 November as the company's CEO Lionel Souque moved to disassociate them from the sport, calling FIFA's actions in the early days of the tournament "scandalous", and even electing to waive its pre-existing advertising rights.[301][302]

Match incidents

Serbian incidents

"No Surrender" Kosovo flag

Shortly after the Group G Brazil vs Serbia match on 24 November, a flag showing Kosovo as being part of Serbia with words "Нема предаје" (transl. No surrender) was seen hanging in Serbia's locker room.[303] The Football Association of Kosovo sued the Football Association of Serbia and urged FIFA to open an investigation. On 26 November 2022, FIFA opened proceedings against the Football Association of Serbia due on the basis of article 11 of the FIFA Disciplinary Code and article 4 of the Regulations for the FIFA World Cup 2022.[304][305][306] The Football Association of Serbia was subsequently fined 20,000 Swiss francs by FIFA on 7 December.[307]

Serbia vs Switzerland group stage

During the Group G Serbia vs Switzerland match on 2 December, midfielder Granit Xhaka twice rattled the entire Serbian team. First, in the 65th minute, Xhaka grabbed his crotch in the direction of Serbian players, causing the entire Serbian bench to angrily respond to him and Serbian reserve goalkeeper Predrag Rajković being booked (i.e. given a yellow card). Second, at the end of the match, Xhaka got into a fight against Nikola Milenković for his chants against Serbians, with both players going into the referee's book.[308]

Between the two incidents between Xhaka and the Serbian players, FIFA issued a public address in the 77th minute of the game asking for "discriminatory chants and gestures" to stop.[309]

Furthermore, Xhaka, an ethnic

FIFA later opened a disciplinary proceeding against Serbia over the breach of three of FIFA's articles, including misconduct of players, discrimination, and order and security at matches.[311]

Croatian incidents

Xenophobic chants were reported during the course of the Group F Croatia vs Canada match on 27 November. During the match, Croatian fans chanted xenophobic anti-Serb slogans against Canadian goalkeeper Milan Borjan, an ethnic Serb who was born in Croatia and fled the country during the Croatian War of Independence.[312] They also displayed a modified John Deere banner making a reference to Operation Storm, a military operation that ended the war and abolished the Republic of Serbian Krajina, which resulted in a mass exodus, ethnnic cleansing and war crimes against its civilian Serb residents.[313][314][315]

FIFA opened a disciplinary measure against Croatia over these incidents after the Canadian Soccer Association filed a complaint.[316] On 7 December, the Croatian Football Federation was fined 50,000 Swiss francs due to violating article 16 of the FIFA Disciplinary Code.[307]

Pitch invasions

A

Another person interrupted the Group D Tunisia vs France match on 30 November by running into the pitch carrying a Palestinian flag.[318]

Netherlands vs Argentina quarter-final

Spanish referee Antonio Mateu Lahoz officiated the second quarter-final, held on 9 December, a game between the Netherlands and Argentina. Mateu Lahoz's decision-making throughout this game was called into question by many of those involved, as well as by neutral observers. BBC presenter Gary Lineker at one point during the game commented: "13 yellow cards. This referee has always loved to be the centre of attention. Makes Mike Dean seem shy."[319] Ultimately, Mateu Lahoz produced a FIFA World Cup record of 18 yellow cards, including to people who were sitting on the bench and thus not involved in the game.[320][321] After the end of the game, Mateu Lahoz issued a red card to Netherlands player Denzel Dumfries, however no TV commentator picked up on this, leaving viewers who checked the match reports afterwards puzzled.[319][322] During the extra time period (which resulted from Netherlands striker Wout Weghorst scoring an equalising goal with the last kick of normal time, which itself went on for ten minutes extra due to the number of stoppages), BBC commentator Martin Keown remarked: "I think the referee is losing the plot here."[323]

Earlier, and with Argentina giving up a two-goal lead to leave the score at 2–1, Argentina's Leandro Paredes fouled his opponent Nathan Aké. Paredes responded to the referee's whistle by taking his foot to the ball and blasting it at the bench on which staff and players from the Netherlands were seated. Staff and players from the Netherlands all poured onto the pitch in anger, followed by staff and players from Argentina, sparking an on-pitch brawl featuring players and substitutes. Netherlands captain Virgil van Dijk was seen to charge forward and knock Paredes to the ground.[324] Given the general confusion surrounding the game's total of yellow cards and the contradictions when various match reports are viewed, it is unclear how many players Lahoz booked in this one incident.

After the game Lionel Messi asked FIFA to get rid of Mateu Lahoz.[325] Messi also criticised the Netherlands manager: "Louis van Gaal says they play good football, but what he did was put tall people and spam long balls" and blamed Lahoz for causing the game to go on longer than it should have: "The referee sent us into extra time".[326] The referee's decision not to show the yellow card to Messi for a deliberate handball also attracted comment, though Messi eventually succumbed to Mateu Lahoz's book in the 10th minute of injury time at the end of the second half, at which point he would have been sent off with a red card if he had been booked for the earlier foul.[327][328] Argentina's goalkeeper Emiliano Martínez described Mateu Lahoz as "crazy, the worst referee of the tournament, he is arrogant. You say something to him and he talks back to you badly. I think since Spain went out [to Morocco in the Round of 16] he wanted us to go out as well".[329]

Immediately following the penalty shootout victory, several Argentina players goaded the losing Netherlands players, e.g. Nicolás Otamendi raised his hands behind his ears, Leandro Paredes and Gonzalo Montiel gestured directly at them, while Alexis Mac Allister, Germán Pezzella and Ángel Di María screamed at their beaten opponents.[330]

Messi, while giving a post-match interview, said to Wout Weghorst: "What you looking at, fool? Go on, get back there."[331]

Controversial goals

Japan 2–1 Spain: Tanaka 51'

In the

Tunisia 1–0 France: Griezmann 90+8' disallowed

Viewers tuning in to French television for the Group D Tunisia vs France match on 30 November missed that the French team had lost the game 1–0. TF1 switched to an ad after Antoine Griezmann had seemingly levelled the game late in stoppage time, causing French viewers to miss the pitchside monitor consultation that led VAR to rule that Griezmann had been offside. The goal was chalked off. French football supporters awoke in shock the following morning to belatedly discover that the game had not ended in a tie at all, but in a surprise defeat for the reigning world champions. The incident brought to mind the time British broadcaster ITV cut for an ad break and viewers missed Steven Gerrard scoring England's opening goal at the 2010 FIFA World Cup.[339][340]

England 1–2 France: Tchouaméni 17'

The first goal scored in the quarter-final between England and France – by Aurélien Tchouaméni for France in the 17th minute – was questioned by some of the British pundits due to England player Bukayo Saka being taken to the ground in order for France to win possession in the build-up to the goal. While some of the pundits thought it was a clear foul during the attacking phase, others thought that the contact was not clear enough for VAR to overturn the on-pitch decision, a view with which some British journalists agreed.[341][342][343]

Post-match incidents

Moroccan riots

Following the

Uruguayans after Ghana game

The Group H Ghana vs Uruguay match on 2 December finished in a 2–0 victory for Uruguay; however, Uruguay failed to progress from the group. After the final whistle, several Uruguayan players confronted the referee and other FIFA officials over what they deemed as controversial decisions during the course of the game, and while walking down the tunnel towards the dressing rooms, Edinson Cavani pushed over the VAR monitor.[348] FIFA notified the Uruguayan association that an investigation was underway on the insults and treatment that Cavani, José María Giménez and Luis Suárez allegedly gave to said FIFA officials, sparking fears of severe punishments similar to the one that Suárez received in 2014 after biting an opponent.[349][350]

Samuel Eto'o assault

Following the Group G Cameroon vs Brazil match on 2 December, Samuel Eto'o assaulted a man outside Stadium 974. A video circulated on social media of the former Cameroon international and Barcelona player, who was Cameroonian Football Federation president, attacking the man. Eto'o said himself, in a statement issued later that week, that it was a "violent altercation", that it was "an unfortunate incident" and that his victim was "probably" a fan of Algeria.[351]

Transportation

At the opening of the

Roads and highways

According to a staff writer for BQ in 2014, "Qatar currently has about 2,500 km of highways and the set plan is for 8,500 kilometres (5,300 mi) by 2020, in addition to public transport bus lines". The writer quoted Jassim bin Saif Al Sulaiti, Minister of transport, who said "local roads now extend to an area covering 9,500 kilometres (5,900 mi) and the set plan is to increase this area to cover 34,000 kilometres (21,000 mi) 2020. We currently have 160 bridges connecting roads and it is expected that the number of bridges would reach 200 by 2020, in addition to increasing the number of tunnels from the current one to 32 in the future".[353]

Public transport

According to a staff writer for BQ, "work is underway to improve the public bus service and infrastructure and a plan of action has been drawn up covering a period of five years". The writer quoted Jassim bin Saif Al Sulaiti, Minister of transport, who said "Qatar has allocated QR 5 billion over the next five years to develop the current fleet of 400 buses in the public transport company to a network of 2,000 buses".[353]

References

- ^ from the original on 19 November 2022. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ from the original on 21 November 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Reuters (16 November 2022). "FIFA World Cup 2022: Why Qatar is a controversial location for the tournament". Times of India. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ from the original on 27 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ Tony Manfred (1 March 2015). "14 reasons the Qatar World Cup is going to be a disaster". Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ "2022 World Cup: Criticism of Qatar finds unequal resonance around the world". Le Monde.fr. 14 November 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ a b Baxter, Kevin (20 November 2022). "Qatar walks tightrope between Arab values and Western norms with World Cup gamble". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Sullivan, Becky (18 November 2022). "Why Qatar is a controversial host for the World Cup". NPR. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ a b Alam, Niaz (18 November 2022). "Corruption beats boycotts". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ a b Benedetti, Eliezer (20 November 2022). ""15.000 muertos por 5.760 minutos de fútbol": ¿Qué es #BoycottQatar2022 y por qué es tendencia todos los días?". El Comercio (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Sepp Blatter: Former FIFA president admits decision to award the World Cup to Qatar was a 'mistake'". Sky Sports. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ "Sepp Blatter: awarding 2022 World Cup to Qatar was a mistake". the Guardian. 16 May 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ a b "World Cup announce questionable attendance figures with capacities exceeded at stadiums". the Guardian. 22 November 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ "In defence of Qatar's hosting of the World Cup". The Economist. 19 November 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d Montague, James (1 May 2013). "Desert heat: World Cup hosts Qatar face scrutiny over 'slavery' accusations". CNN. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013.

- ^ Morin, Richard (12 April 2013). "Indentured Servitude in the Persian Gulf". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ^ "Qatar: End corporate exploitation of migrant construction workers". Amnesty International. 17 November 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help) - ^ Rights, Migrant (6 October 2015). "Qatar: No country for migrant men". migrant-rights.org. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ "KNVB leader Michael van Praag to run for FIFA president against Sepp Blatter". ESPN. 26 January 2015. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018.

- ^ a b c Gibson, Owen (18 February 2014). "More than 500 Indian Workers Have Died in Qatar Since 2012, Figures Show". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Pete Pattisson (1 September 2020). "New Labour Law Ends Qatar's Exploitative Kafala System". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Booth, Robert. "Qatar World Cup construction 'will leave 4,000 migrant workers dead'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 May 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ^ "Fifa 2022 World Cup: Is Qatar doing enough to save migrant workers' lives?". ITV News. 8 June 2015. Archived from the original on 7 March 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ a b c Stephenson, Wesley (6 June 2015). "Have 1,200 World Cup workers really died in Qatar?". BBC. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ Pattisson, Pete (25 September 2013). "Revealed: Qatar's World Cup 'slaves'". The Guardian (UK). Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ Pattisson, Pete; Khalili, Mustafa (25 September 2013). "Qatar: the migrant workers forced to work for no pay in World Cup host country – video". The Guardian (UK).

- ^ "Qatar World Cup: Stadium builders working in 'sub-human' conditions". The Daily Telegraph. London. 6 April 2014.

- ^ Saraswathi, Vani (6 November 2016). "Qatar's Kafala reforms: A ready reckoner - Migrant RightsMigrant Rights". Migrant Rights. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ "Still Slaving Away". The Economist. 6 June 2015. pp. 38–39.

- ^ "evidence of forced labour on the Qatar 2022 World Cup infrastructure project". ESPN. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013.