Cloning: Difference between revisions

Rescuing 2 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.6.1) (Feminist) |

|||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

* [[Tadpole]]: (1952) [[Robert Briggs (scientist)|Robert Briggs]] and [[Thomas Joseph King|Thomas J. King]] had [[List of animals that have been cloned#Frog (tadpole)|successfully cloned northern leopard frogs]]: thirty-five complete embryos and twenty-seven tadpoles from one-hundred and four successful nuclear transfers.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://library.thinkquest.org/24355/data/details/1952.html|title=ThinkQuest|publisher=|accessdate=3 May 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.nap.edu/readingroom/books/biomems/rbriggs.html | title=Robert W. Briggs | publisher=National Academies Press | accessdate=1 December 2012}}</ref> |

* [[Tadpole]]: (1952) [[Robert Briggs (scientist)|Robert Briggs]] and [[Thomas Joseph King|Thomas J. King]] had [[List of animals that have been cloned#Frog (tadpole)|successfully cloned northern leopard frogs]]: thirty-five complete embryos and twenty-seven tadpoles from one-hundred and four successful nuclear transfers.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://library.thinkquest.org/24355/data/details/1952.html|title=ThinkQuest|publisher=|accessdate=3 May 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.nap.edu/readingroom/books/biomems/rbriggs.html | title=Robert W. Briggs | publisher=National Academies Press | accessdate=1 December 2012}}</ref> |

||

* [[Carp]]: (1963) In [[China]], [[embryologist]] [[Tong Dizhou]] produced the world's [[List of animals that have been cloned#Carp|first cloned fish]] by inserting the DNA from a cell of a male carp into an egg from a female carp. He published the findings in a Chinese science journal.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.pbs.org/bloodlines/timeline/text_timeline.html |title=Bloodlines timeline |date= |work= |publisher=PBS.org|accessdate= }}</ref> |

* [[Carp]]: (1963) In [[China]], [[embryologist]] [[Tong Dizhou]] produced the world's [[List of animals that have been cloned#Carp|first cloned fish]] by inserting the DNA from a cell of a male carp into an egg from a female carp. He published the findings in a Chinese science journal.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.pbs.org/bloodlines/timeline/text_timeline.html |title=Bloodlines timeline |date= |work= |publisher=PBS.org|accessdate= }}</ref> |

||

* [[Mice]]: (1986) A mouse was successfully cloned from an early embryonic cell. [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] scientists Chaylakhyan, Veprencev, Sviridova, and Nikitin had the mouse "Masha" cloned. Research was published in the magazine "Biofizika" volume ХХХII, issue 5 of 1987.{{Clarify|date=August 2008}}<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Chaylakhyan | first1 = Levon | journal = Биофизика | title= Электростимулируемое слияние клеток в клеточной инженерии| volume = ХХХII | issue = 5 | pages = 874–887 | doi = | date = 1987 | url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160911074840/http://www.pereplet.ru/nauka/anobele/klon/bio.html | |

* [[Mice]]: (1986) A mouse was successfully cloned from an early embryonic cell. [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] scientists Chaylakhyan, Veprencev, Sviridova, and Nikitin had the mouse "Masha" cloned. Research was published in the magazine "Biofizika" volume ХХХII, issue 5 of 1987.{{Clarify|date=August 2008}}<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Chaylakhyan | first1 = Levon | journal = Биофизика | title = Электростимулируемое слияние клеток в клеточной инженерии | volume = ХХХII | issue = 5 | pages = 874–887 | doi = | date = 1987 | url = http://www.pereplet.ru/nauka/anobele/klon/bio.html | pmid = | pmc = | deadurl = bot: unknown | archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20160911074840/http://www.pereplet.ru/nauka/anobele/klon/bio.html | archivedate = 11 September 2016 | df = dmy-all }}</ref><!-- ideally an English translation is needed; following cite is from an archived copy of the original, now dead, link. A translation appears to indicate that Russians worked with embryonic mouse cells to produce a non-SCNT clone in 1987 --><ref>{{cite web| title=Кто изобрел клонирование?| archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20041223221951/http://www.whoiswho.ru/russian/Curnom/22003/cl.htm| archivedate=2004-12-23| url=http://www.whoiswho.ru/russian/Curnom/22003/cl.htm}} (Russian)</ref> |

||

* [[Domestic sheep|Sheep]]: Marked the first mammal being cloned (1984) from early embryonic cells by [[Steen Willadsen]]. [[Megan and Morag]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/sci_tech/highlights/wilmutt.shtml |title=Gene Genie | BBC World Service |publisher=Bbc.co.uk |date=2000-05-01 |accessdate=2010-08-04}}</ref> cloned from differentiated embryonic cells in June 1995 and [[Dolly the sheep]] from a somatic cell in 1996.<ref>{{cite journal |author=McLaren A |title=Cloning: pathways to a pluripotent future |journal=Science |volume=288 |issue=5472 |pages=1775–80 |year=2000 |pmid=10877698 |doi=10.1126/science.288.5472.1775}}</ref> |

* [[Domestic sheep|Sheep]]: Marked the first mammal being cloned (1984) from early embryonic cells by [[Steen Willadsen]]. [[Megan and Morag]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/sci_tech/highlights/wilmutt.shtml |title=Gene Genie | BBC World Service |publisher=Bbc.co.uk |date=2000-05-01 |accessdate=2010-08-04}}</ref> cloned from differentiated embryonic cells in June 1995 and [[Dolly the sheep]] from a somatic cell in 1996.<ref>{{cite journal |author=McLaren A |title=Cloning: pathways to a pluripotent future |journal=Science |volume=288 |issue=5472 |pages=1775–80 |year=2000 |pmid=10877698 |doi=10.1126/science.288.5472.1775}}</ref> |

||

* [[Rhesus monkey]]: [[Tetra (monkey)|Tetra]] (January 2000) from embryo splitting<ref>[[CNN]]. [http://archives.cnn.com/2000/NATURE/01/13/monkey.cloning/ Researchers clone monkey by splitting embryo] 2000-01-13. Retrieved 2008-08-05.</ref>{{Clarify|date=August 2008}}<!-- see [[Talk:Cloning#]cleanup notes]] - this is not SCNT --><ref>{{cite news|author=Dean Irvine |url=http://edition.cnn.com/2007/WORLD/europe/11/16/ww.humancloning/index.html?iref=allsearch |title=You, again: Are we getting closer to cloning humans? - CNN.com |publisher=Edition.cnn.com |date=2007-11-19 |accessdate=2010-08-04}}</ref> |

* [[Rhesus monkey]]: [[Tetra (monkey)|Tetra]] (January 2000) from embryo splitting<ref>[[CNN]]. [http://archives.cnn.com/2000/NATURE/01/13/monkey.cloning/ Researchers clone monkey by splitting embryo] 2000-01-13. Retrieved 2008-08-05.</ref>{{Clarify|date=August 2008}}<!-- see [[Talk:Cloning#]cleanup notes]] - this is not SCNT --><ref>{{cite news|author=Dean Irvine |url=http://edition.cnn.com/2007/WORLD/europe/11/16/ww.humancloning/index.html?iref=allsearch |title=You, again: Are we getting closer to cloning humans? - CNN.com |publisher=Edition.cnn.com |date=2007-11-19 |accessdate=2010-08-04}}</ref> |

||

| Line 124: | Line 124: | ||

Advocates support development of therapeutic cloning in order to generate tissues and whole organs to treat patients who otherwise cannot obtain transplants,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ornl.gov/sci/techresources/Human_Genome/elsi/cloning.shtml#organsQ |title=Cloning Fact Sheet |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130502125744/http://www.ornl.gov/sci/techresources/Human_Genome/elsi/cloning.shtml |publisher=U.S. Department of Energy Genome Program |date=2009-05-11 |archivedate=2013-05-02}}</ref> to avoid the need for [[immunosuppressive drugs]],<ref name="ncbi.nlm.nih.gov"/> and to stave off the effects of aging.<ref name=EndingAging>de Grey, Aubrey; Rae, Michael (September 2007). ''Ending Aging: The Rejuvenation Breakthroughs that Could Reverse Human Aging in Our Lifetime''. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 416 pp. {{ISBN|0-312-36706-6}}.</ref> Advocates for reproductive cloning believe that parents who cannot otherwise procreate should have access to the technology.<ref>Staff, Times Higher Education. 10 August 2001 [http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/164313.article In the news: Antinori and Zavos]</ref> |

Advocates support development of therapeutic cloning in order to generate tissues and whole organs to treat patients who otherwise cannot obtain transplants,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ornl.gov/sci/techresources/Human_Genome/elsi/cloning.shtml#organsQ |title=Cloning Fact Sheet |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130502125744/http://www.ornl.gov/sci/techresources/Human_Genome/elsi/cloning.shtml |publisher=U.S. Department of Energy Genome Program |date=2009-05-11 |archivedate=2013-05-02}}</ref> to avoid the need for [[immunosuppressive drugs]],<ref name="ncbi.nlm.nih.gov"/> and to stave off the effects of aging.<ref name=EndingAging>de Grey, Aubrey; Rae, Michael (September 2007). ''Ending Aging: The Rejuvenation Breakthroughs that Could Reverse Human Aging in Our Lifetime''. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 416 pp. {{ISBN|0-312-36706-6}}.</ref> Advocates for reproductive cloning believe that parents who cannot otherwise procreate should have access to the technology.<ref>Staff, Times Higher Education. 10 August 2001 [http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/164313.article In the news: Antinori and Zavos]</ref> |

||

Opponents of cloning have concerns that technology is not yet developed enough to be safe<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.aaas.org/spp/sfrl/docs/cloningstatement.shtml| title = AAAS Statement on Human Cloning}}</ref> and that it could be prone to abuse (leading to the generation of humans from whom organs and tissues would be harvested),<ref name="McGee">{{cite web |last=McGee |first=G. |

Opponents of cloning have concerns that technology is not yet developed enough to be safe<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.aaas.org/spp/sfrl/docs/cloningstatement.shtml| title = AAAS Statement on Human Cloning}}</ref> and that it could be prone to abuse (leading to the generation of humans from whom organs and tissues would be harvested),<ref name="McGee">{{cite web |last=McGee |first=G. |title=Primer on Ethics and Human Cloning |date=October 2011 |publisher=American Institute of Biological Sciences |url=http://www.actionbioscience.org/biotech/mcgee.html |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://archive.is/20130223142719/http://www.actionbioscience.org/biotech/mcgee.html |archivedate=23 February 2013 |df=dmy-all }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |publisher=UNESCO |date=1997-11-11 |url=http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13177&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html |title=Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights |accessdate=2008-02-27}}</ref> as well as concerns about how cloned individuals could integrate with families and with society at large.<ref>McGee, Glenn (2000). 'The Perfect Baby: Parenthood in the New World of Cloning and Genetics.' Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.</ref><ref name="Human Cloning Ethics">{{cite journal| author=Havstad JC| title=Human reproductive cloning: a conflict of liberties. | journal=Bioethics | year= 2010 | volume= 24 | issue= 2 | pages= 71–7 | pmid=19076121 | doi=10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00692.x | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=19076121 }}</ref> |

||

Religious groups are divided, with some opposing the technology as usurping "God's place" and, to the extent embryos are used, destroying a human life; others support therapeutic cloning's potential life-saving benefits.<ref>Bob Sullivan, Technology correspondent for MSNBC. November 262003 [http://www.nbcnews.com/id/3076930/#.UqzUNmRDuxg Religions reveal little consensus on cloning – Health – Special Reports – Beyond Dolly: Human Cloning]</ref><ref>William Sims Bainbridge, Ph.D. |

Religious groups are divided, with some opposing the technology as usurping "God's place" and, to the extent embryos are used, destroying a human life; others support therapeutic cloning's potential life-saving benefits.<ref>Bob Sullivan, Technology correspondent for MSNBC. November 262003 [http://www.nbcnews.com/id/3076930/#.UqzUNmRDuxg Religions reveal little consensus on cloning – Health – Special Reports – Beyond Dolly: Human Cloning]</ref><ref>William Sims Bainbridge, Ph.D. |

||

Revision as of 11:20, 22 December 2017

In biology, cloning is the process of producing similar populations of genetically identical individuals that occurs in nature when organisms such as bacteria, insects or plants reproduce asexually. Cloning in biotechnology refers to processes used to create copies of DNA fragments (molecular cloning), cells (cell cloning), or organisms. The term also refers to the production of multiple copies of a product such as digital media or software.

The term clone, invented by J. B. S. Haldane, is derived from the Ancient Greek word κλών klōn, "twig", referring to the process whereby a new plant can be created from a twig. In horticulture, the spelling clon was used until the twentieth century; the final e came into use to indicate the vowel is a "long o" instead of a "short o".[1][2] Since the term entered the popular lexicon in a more general context, the spelling clone has been used exclusively.

In botany, the term lusus was traditionally used.[3]: 21, 43

Natural cloning

Cloning is a natural form of reproduction that has allowed life forms to spread for more than 50 thousand years. It is the reproduction method used by

Molecular cloning

Molecular cloning refers to the process of making multiple molecules. Cloning is commonly used to amplify

Cloning of any DNA fragment essentially involves four steps[8]

- fragmentation - breaking apart a strand of DNA

- ligation - gluing together pieces of DNA in a desired sequence

- transfection – inserting the newly formed pieces of DNA into cells

- screening/selection – selecting out the cells that were successfully transfected with the new DNA

Although these steps are invariable among cloning procedures a number of alternative routes can be selected; these are summarized as a cloning strategy.

Initially, the DNA of interest needs to be isolated to provide a DNA segment of suitable size. Subsequently, a ligation procedure is used where the amplified fragment is inserted into a

Cell cloning

Cloning unicellular organisms

Cloning a cell means to derive a population of cells from a single cell. In the case of unicellular organisms such as bacteria and yeast, this process is remarkably simple and essentially only requires the inoculation of the appropriate medium. However, in the case of cell cultures from multi-cellular organisms, cell cloning is an arduous task as these cells will not readily grow in standard media.

A useful tissue culture technique used to clone distinct lineages of cell lines involves the use of cloning rings (cylinders).

Cloning stem cells

Therapeutic cloning is achieved by creating embryonic stem cells in the hopes of treating diseases such as diabetes and Alzheimer's. The process begins by removing the nucleus (containing the DNA) from an egg cell and inserting a nucleus from the adult cell to be cloned.[11] In the case of someone with Alzheimer's disease, the nucleus from a skin cell of that patient is placed into an empty egg. The reprogrammed cell begins to develop into an embryo because the egg reacts with the transferred nucleus. The embryo will become genetically identical to the patient.[11] The embryo will then form a blastocyst which has the potential to form/become any cell in the body.[12]

The reason why SCNT is used for cloning is because somatic cells can be easily acquired and cultured in the lab. This process can either add or delete specific genomes of farm animals. A key point to remember is that cloning is achieved when the oocyte maintains its normal functions and instead of using sperm and egg genomes to replicate, the oocyte is inserted into the donor’s somatic cell nucleus.[13] The oocyte will react on the somatic cell nucleus, the same way it would on sperm cells.[13]

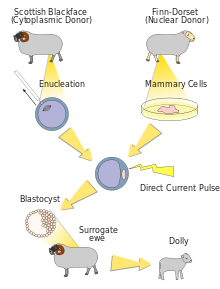

The process of cloning a particular farm animal using SCNT is relatively the same for all animals. The first step is to collect the somatic cells from the animal that will be cloned. The somatic cells could be used immediately or stored in the laboratory for later use.[13] The hardest part of SCNT is removing maternal DNA from an oocyte at metaphase II. Once this has been done, the somatic nucleus can be inserted into an egg cytoplasm.[13] This creates a one-cell embryo. The grouped somatic cell and egg cytoplasm are then introduced to an electrical current.[13] This energy will hopefully allow the cloned embryo to begin development. The successfully developed embryos are then placed in surrogate recipients, such as a cow or sheep in the case of farm animals.[13]

SCNT is seen as a good method for producing agriculture animals for food consumption. It successfully cloned sheep, cattle, goats, and pigs. Another benefit is SCNT is seen as a solution to clone endangered species that are on the verge of going extinct.[13] However, stresses placed on both the egg cell and the introduced nucleus can be enormous, which led to a high loss in resulting cells in early research. For example, the cloned sheep Dolly was born after 277 eggs were used for SCNT, which created 29 viable embryos. Only three of these embryos survived until birth, and only one survived to adulthood.[14] As the procedure could not be automated, and had to be performed manually under a microscope, SCNT was very resource intensive. The biochemistry involved in reprogramming the differentiated somatic cell nucleus and activating the recipient egg was also far from being well understood. However, by 2014 researchers were reporting cloning success rates of seven to eight out of ten[15] and in 2016, a Korean Company Sooam Biotech was reported to be producing 500 cloned embryos per day.[16]

In SCNT, not all of the donor cell's genetic information is transferred, as the donor cell's

Organism cloning

Organism cloning (also called reproductive cloning) refers to the procedure of creating a new multicellular organism, genetically identical to another. In essence this form of cloning is an asexual method of reproduction, where fertilization or inter-gamete contact does not take place. Asexual reproduction is a naturally occurring phenomenon in many species, including most plants (see vegetative reproduction) and some insects. Scientists have made some major achievements with cloning, including the asexual reproduction of sheep and cows. There is a lot of ethical debate over whether or not cloning should be used. However, cloning, or asexual propagation,[17] has been common practice in the horticultural world for hundreds of years.

Horticultural

The term clone is used in horticulture to refer to descendants of a single plant which were produced by vegetative reproduction or apomixis. Many horticultural plant cultivars are clones, having been derived from a single individual, multiplied by some process other than sexual reproduction.[18] As an example, some European cultivars of grapes represent clones that have been propagated for over two millennia. Other examples are potato and banana.[19] Grafting can be regarded as cloning, since all the shoots and branches coming from the graft are genetically a clone of a single individual, but this particular kind of cloning has not come under ethical scrutiny and is generally treated as an entirely different kind of operation.

Many

, resulting in clonal populations of genetically identical individuals.Parthenogenesis

Clonal derivation exists in nature in some animal species and is referred to as

Artificial cloning of organisms

Artificial cloning of organisms may also be called reproductive cloning.

First moves

Methods

Reproductive cloning generally uses "somatic cell nuclear transfer" (SCNT) to create animals that are genetically identical. This process entails the transfer of a nucleus from a donor adult cell (somatic cell) to an egg from which the nucleus has been removed, or to a cell from a blastocyst from which the nucleus has been removed.[23] If the egg begins to divide normally it is transferred into the uterus of the surrogate mother. Such clones are not strictly identical since the somatic cells may contain mutations in their nuclear DNA. Additionally, the mitochondria in the cytoplasm also contains DNA and during SCNT this mitochondrial DNA is wholly from the cytoplasmic donor's egg, thus the mitochondrial genome is not the same as that of the nucleus donor cell from which it was produced. This may have important implications for cross-species nuclear transfer in which nuclear-mitochondrial incompatibilities may lead to death.

Artificial embryo splitting or embryo twinning, a technique that creates monozygotic twins from a single embryo, is not considered in the same fashion as other methods of cloning. During that procedure, a donor

Dolly the sheep

Dolly was publicly significant because the effort showed that genetic material from a specific adult cell, programmed to express only a distinct subset of its genes, can be reprogrammed to grow an entirely new organism. Before this demonstration, it had been shown by John Gurdon that nuclei from differentiated cells could give rise to an entire organism after transplantation into an enucleated egg.[30] However, this concept was not yet demonstrated in a mammalian system.

The first mammalian cloning (resulting in Dolly the sheep) had a success rate of 29 embryos per 277 fertilized eggs, which produced three lambs at birth, one of which lived. In a bovine experiment involving 70 cloned calves, one-third of the calves died young. The first successfully cloned horse, Prometea, took 814 attempts. Notably, although the first[clarification needed] clones were frogs, no adult cloned frog has yet been produced from a somatic adult nucleus donor cell.

There were early claims that

Dolly was named after performer Dolly Parton because the cells cloned to make her were from a mammary gland cell, and Parton is known for her ample cleavage.[32]

Species cloned

The modern cloning techniques involving nuclear transfer have been successfully performed on several species. Notable experiments include:

- Tadpole: (1952) Robert Briggs and Thomas J. King had successfully cloned northern leopard frogs: thirty-five complete embryos and twenty-seven tadpoles from one-hundred and four successful nuclear transfers.[33][34]

- embryologist Tong Dizhou produced the world's first cloned fish by inserting the DNA from a cell of a male carp into an egg from a female carp. He published the findings in a Chinese science journal.[35]

- Mice: (1986) A mouse was successfully cloned from an early embryonic cell. Soviet scientists Chaylakhyan, Veprencev, Sviridova, and Nikitin had the mouse "Masha" cloned. Research was published in the magazine "Biofizika" volume ХХХII, issue 5 of 1987.[clarification needed][36][37]

- Dolly the sheep from a somatic cell in 1996.[39]

- BGI in China was producing 500 cloned pigs a year to test new medicines.[43]

- Gaur: (2001) was the first endangered species cloned.[44]

- Cattle: Alpha and Beta (males, 2001) and (2005) Brazil[45]

- Cat: CopyCat "CC" (female, late 2001), Little Nicky, 2004, was the first cat cloned for commercial reasons[46]

- Ralph, the first cloned rat (2003)[47]

- Mule: Idaho Gem, a john mule born 4 May 2003, was the first horse-family clone.[48]

- Horse: Prometea, a Haflinger female born 28 May 2003, was the first horse clone.[49]

- Afghan hound was the first cloned dog (2005).[50]

- Wolf: Snuwolf and Snuwolffy, the first two cloned female wolves (2005).[51]

- Pyrenean ibex (2009) was the first extinct animal to be cloned back to life; the clone lived for seven minutes before dying of lung defects.[53][54]

- Injaz, is the first cloned camel.[55]

- Pashmina goat: (2012) Noori, is the first cloned pashmina goat. Scientists at the faculty of veterinary sciences and animal husbandry of Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Kashmir successfully cloned the first Pashmina goat (Noori) using the advanced reproductive techniques under the leadership of Riaz Ahmad Shah.[56]

- Gastric brooding frog: (2013) The gastric brooding frog, Rheobatrachus silus, thought to have been extinct since 1983 was cloned in Australia, although the embryos died after a few days.[57]

Human cloning

Human cloning is the creation of a genetically identical copy of a human. The term is generally used to refer to artificial human cloning, which is the reproduction of human cells and tissues. It does not refer to the natural conception and delivery of

Two commonly discussed types of theoretical human cloning are therapeutic cloning and reproductive cloning. Therapeutic cloning would involve cloning cells from a human for use in medicine and transplants, and is an active area of research, but is not in medical practice anywhere in the world, as of 2014. Two common methods of therapeutic cloning that are being researched are

Ethical issues of cloning

There are a variety of

Advocates support development of therapeutic cloning in order to generate tissues and whole organs to treat patients who otherwise cannot obtain transplants,

Opponents of cloning have concerns that technology is not yet developed enough to be safe[62] and that it could be prone to abuse (leading to the generation of humans from whom organs and tissues would be harvested),[63][64] as well as concerns about how cloned individuals could integrate with families and with society at large.[65][66]

Religious groups are divided, with some opposing the technology as usurping "God's place" and, to the extent embryos are used, destroying a human life; others support therapeutic cloning's potential life-saving benefits.[67][68]

Cloning of animals is opposed by animal-groups due to the number of cloned animals that suffer from malformations before they die,[69][70] and while food from cloned animals has been approved by the US FDA,[71][72] its use is opposed by groups concerned about food safety.[73][74][75]

Cloning extinct and endangered species

Cloning, or more precisely, the reconstruction of functional DNA from

In 2001, a cow named Bessie gave birth to a cloned Asian gaur, an endangered species, but the calf died after two days. In 2003, a banteng was successfully cloned, followed by three African wildcats from a thawed frozen embryo. These successes provided hope that similar techniques (using surrogate mothers of another species) might be used to clone extinct species. Anticipating this possibility, tissue samples from the last bucardo (Pyrenean ibex) were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after it died in 2000. Researchers are also considering cloning endangered species such as the giant panda and cheetah.

In 2002, geneticists at the

In January 2009, for the first time, an extinct animal, the Pyrenean ibex mentioned above was cloned, at the Centre of Food Technology and Research of Aragon, using the preserved frozen cell nucleus of the skin samples from 2001 and domestic goat egg-cells. The ibex died shortly after birth due to physical defects in its lungs.[85]

One of the most anticipated targets for cloning was once the woolly mammoth, but attempts to extract DNA from frozen mammoths have been unsuccessful, though a joint Russo-Japanese team is currently working toward this goal. In January 2011, it was reported by Yomiuri Shimbun that a team of scientists headed by Akira Iritani of Kyoto University had built upon research by Dr. Wakayama, saying that they will extract DNA from a mammoth carcass that had been preserved in a Russian laboratory and insert it into the egg cells of an African elephant in hopes of producing a mammoth embryo. The researchers said they hoped to produce a baby mammoth within six years.[86][87] It was noted, however that the result, if possible, would be an elephant-mammoth hybrid rather than a true mammoth.[88] Another problem is the survival of the reconstructed mammoth: ruminants rely on a symbiosis with specific microbiota in their stomachs for digestion.[88]

Scientists at the University of Newcastle and University of New South Wales announced in March 2013 that the very recently extinct gastric-brooding frog would be the subject of a cloning attempt to resurrect the species.[89]

Many such "de-extinction" projects are described in the Long Now Foundation's Revive and Restore Project.[90]

Lifespan

After an eight-year project involving the use of a pioneering cloning technique, Japanese researchers created 25 generations of healthy cloned mice with normal lifespans, demonstrating that clones are not intrinsically shorter-lived than naturally born animals.[31][91] Other sources have noted that the offspring of clones tend to be healthier than the original clones and indistinguishable from animals produced naturally.[92]

In a detailed study released in 2016 and less detailed studies by others suggest that once cloned animals get past the first month or two of life they are generally healthy. However, early pregnancy loss and neonatal losses are still greater with cloning than natural conception or assisted reproduction (IVF). Current research endeavors are attempting to overcome this problem.[32]

In popular culture

Discussion of cloning in the popular media often presents the subject negatively. In an article in the 8 November 1993 article of

The concept of cloning has featured a wide variety of

Cloning is a recurring theme in a number of contemporary science fiction films, ranging from action films such as Jurassic Park (1993), Alien Resurrection (1997), The 6th Day (2000), Resident Evil (2002), Star Wars: Episode II (2002) and The Island (2005), to comedies such as Woody Allen's 1973 film Sleeper.[98]

The process of cloning is represented in different ways in fiction. Many works depict the artificial creation of humans by a method of growing cells from a tissue or DNA sample; the process may instantaneous, or take place through a slow process of growing human embryos in

Cloning humans from body parts is also a common theme in science fiction. Cloning features strongly among the science fiction conventions parodied in Woody Allen's Sleeper, the plot of which centres around an attempt to clone an assassinated dictator from his disembodied nose.[101] In the 2008 Doctor Who story "Journey's End", a duplicate version of the Tenth Doctor spontaneously grows from his severed hand, which had been cut off in a sword fight during an earlier episode.[102]

Cloning and identity

Science fiction has used cloning, most commonly and specifically human cloning, due to the fact that it brings up controversial questions of identity.

In 2012, a Japanese television series named "Bunshin" was created. The story's main character, Mariko, is a woman studying child welfare in Hokkaido. She grew up always doubtful about the love from her mother, who looked nothing like her and who died nine years before. One day, she finds some of her mother's belongings at a relative's house, and heads to Tokyo to seek out the truth behind her birth. She later discovered that she was a clone.[106]

In the 2013 television series Orphan Black, cloning is used as a scientific study on the behavioral adaptation of the clones.[107] In a similar vein, the book The Double by Nobel Prize winner José Saramago explores the emotional experience of a man who discovers that he is a clone.[108]

Cloning as resurrection

Cloning has been used in fiction as a way of recreating historical figures. In the 1976 Ira Levin novel The Boys from Brazil and its 1978 film adaptation, Josef Mengele uses cloning to create copies of Adolf Hitler.[109]

In

Cloning for warfare

The use of cloning for military purposes has also been explored in several works. In Doctor Who, an alien race of armour-clad, warlike beings called Sontarans was introduced in the 1973 serial "The Time Warrior". Sontarans are depicted as squat, bald creatures who have been genetically engineered for combat. Their weak spot is a "probic vent", a small socket at the back of their neck which is associated with the cloning process.[111] The concept of cloned soldiers being bred for combat was revisited in "The Doctor's Daughter" (2008), when the Doctor's DNA is used to create a female warrior called Jenny.[112]

The 1977 film

Cloning for exploitation

A recurring sub-theme of cloning fiction is the use of clones as a supply of

The exploitation of human clones for dangerous and undesirable work was examined in the 2009 British science fiction film Moon.[117] In the futuristic novel Cloud Atlas and subsequent film, one of the story lines focuses on a genetically-engineered fabricant clone named Sonmi~451 who is one of millions raised in an artificial "wombtank," destined to serve from birth. She is one of thousands of clones created for manual and emotional labor; Sonmi herself works as a server in a restaurant. She later discovers that the sole source of food for clones, called 'Soap', is manufactured from the clones themselves.[118]

See also

- The President's Council on Bioethics

- The Frozen Ark

Notes

References

- ^ "Torrey Botanical Club: Volumes 42–45". Torreya. 42–45. Torrey Botanical Club: 133. 1942Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ American Association for the Advancement of Science (1903). Science. Moses King. pp. 502–. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- ^ de Candolle, A. (1868). Laws of Botanical Nomenclature adopted by the International Botanical Congress held at Paris in August 1867; together with an Historical Introduction and Commentary by Alphonse de Candolle, Translated from the French. translated by H.A. Weddell. London: L. Reeve and Co.

- ^ "Tasmanian bush could be oldest living organism". Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on 23 July 2006. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ibiza's Monster Marine Plant". Ibiza Spotlight. Archived from the original on 26 December 2007. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - .

- ^ "Blackwell Publishing Ltd Clonal dynamics in western North American aspen (Populus tremuloides)". U.S. Department of Agriculture, Oxford, UK : Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2008. p. 17. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ISBN 0-8053-4665-1.

- PMID 10650336.

- ^ Gil, Gideon (17 January 2008). "California biotech says it cloned a human embryo, but no stem cells produced". Boston Globe.

- ^ a b Halim, N. (September 2002). "Extensive new study shows abnormalities in cloned animals". Massachusetts institute of technology. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Plus, M. (2011). "Fetal development". Nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Latham, K. E. (2005). "Early and delayed aspects of nuclear reprogramming during cloning" (PDF). Biology of the Cell. pp. 97, 119–132.

- )

- ^ Shukman, David (14 January 2014) China cloning on an 'industrial scale' BBC News Science and Environment, Retrieved 10 April 2014

- ^ Zastrow, Mark (8 February 2016). "Inside the cloning factory that creates 500 new animals a day". New Scientist. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Asexual Propagation". Aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ Sagers, Larry A. (2 March 2009) Proliferate favorite trees by grafting, cloning Utah Stae University, Deseret News (Salt Lake City) Retrieved 21 February 2014

- PMID 21730145.

- ^ Castagnone-Sereno P, et al. Diversity and evolution of root-knot nematodes, genus Meloidogyne: new insights from the genomic era Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2013;51:203-20

- ^ a b Shubin, Neil (24 February 2008) Birds Do It. Bees Do It. Dragons Don’t Need To New York Times, Retrieved 21 February 2014

- ^ "Cloning Fact Sheet". Human Genome Project Information. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- )

- ISBN 0-8126-9375-2.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Swedin, Eric. "Cloning". CredoReference. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- .

- ^ Swedin, Eric. "Cloning". CredoReference. Science in the Contemporary World. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ^ TV documentary Visions Of The Future part 2 shows this process, explores the social implicatins of cloning and contains footage of monoculture in livestock

- PMID 13903027.

- ^ )

- ^ a b BBC. 22 February 2008. BBC On This Day: 1997: Dolly the sheep is cloned

- ^ "ThinkQuest". Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Robert W. Briggs". National Academies Press. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ "Bloodlines timeline". PBS.org.

- ^ Chaylakhyan, Levon (1987). "Электростимулируемое слияние клеток в клеточной инженерии". Биофизика. ХХХII (5): 874–887. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Кто изобрел клонирование?". Archived from the original on 23 December 2004. (Russian)

- ^ "Gene Genie | BBC World Service". Bbc.co.uk. 1 May 2000. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- PMID 10877698.

- ^ CNN. Researchers clone monkey by splitting embryo 2000-01-13. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ^ Dean Irvine (19 November 2007). "You, again: Are we getting closer to cloning humans? - CNN.com". Edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- doi:10.1038/74335.

- ^ Shukman, David (14 January 2014) China cloning on an 'industrial scale' BBC News Science and Environment, Retrieved 14 January 2014

- ^ "First cloned endangered species dies 2 days after birth". CNN. 12 January 2001. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Camacho, Keite. Embrapa clona raça de boi ameaçada de extinção. Agência Brasil. 2005-05-20. (Portuguese) Retrieved 2008-08-05

- ^ "Americas | Pet kitten cloned for Christmas". BBC News. 23 December 2004. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ "Rat called Ralph is latest clone". BBC News. 25 September 2003. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Associated Press 25 August 2009 (25 August 2009). "Gordon Woods dies at 57; Veterinary scientist helped create first cloned mule". latimes.com. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "World's first cloned horse is born – 06 August 2003". New Scientist. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ "First Dog Clone". News.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ (1 September 2009) World's first cloned wolf dies Phys.Org, Retrieved 9 April 2015

- ^ Sinha, Kounteya (13 February 2009). "India clones world's first buffalo". The Times of India. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- Spanish ibex, is thriving. Peter Maas. Pyrenean Ibex – Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica Archived 27 June 2012 at the Wayback Machineat The Sixth Extinction]. Last updated 15 April 2012.

- ^ Extinct ibex is resurrected by cloning, The Daily Telegraph, 31 January 2009

- Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- ^ Ishfaq-ul-Hassan (15 March 2012). "India gets its second cloned animal Noorie, a pashmina goat". Kashmir, India: DNA.

- ^ Hickman, L. "Scientists clone extinct frog – Jurassic Park here we come?". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ PMID 18523539.

- ^ "Cloning Fact Sheet". U.S. Department of Energy Genome Program. 11 May 2009. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013.

- ISBN 0-312-36706-6.

- ^ Staff, Times Higher Education. 10 August 2001 In the news: Antinori and Zavos

- ^ "AAAS Statement on Human Cloning".

- ^ McGee, G. (October 2011). "Primer on Ethics and Human Cloning". American Institute of Biological Sciences. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights". UNESCO. 11 November 1997. Retrieved 27 February 2008.

- ^ McGee, Glenn (2000). 'The Perfect Baby: Parenthood in the New World of Cloning and Genetics.' Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- PMID 19076121.

- ^ Bob Sullivan, Technology correspondent for MSNBC. November 262003 Religions reveal little consensus on cloning – Health – Special Reports – Beyond Dolly: Human Cloning

- ^ William Sims Bainbridge, Ph.D. Religious Opposition to Cloning[permanent dead link] Journal of Evolution and Technology – Vol. 13 – October 2003

- ^ Staff, Humane Society Cloning

- ^ Sean Poulter for the Daily Mail. 26 November 2010. Clone farming would introduce cruelty on a massive scale, say animal welfare groups

- PMID 23829575.

- ^ "FDA says cloned animals are OK to eat". NBCNews.com. Associated Press. 28 December 2006.

- ^ "An HSUS Report: Welfare Issues with Genetic Engineering and Cloning of Farm Animals" (PDF). Humane Society of the United States.

- ^ "Not Ready for Prime Time: FDA's Flawed Approach to Assessing the Safety of Food from Animal Clones" (PDF). Center for Food Safety. March 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)(PDF) - Consumers Union.

- ^ a b Holt, W. V., Pickard, A. R., & Prather, R. S. (2004) Wildlife conservation and reproductive cloning. Reproduction, 126.

- PMID 16909565.

- )

- ^ Shukman, David (14 January 2014) China cloning on an 'industrial scale' BBC News Science and Environment, Retrieved 27 February 2016

- ^ Baer, Drake (8 September 2015). "This Korean lab has nearly perfected dog cloning, and that's just the start". Tech Insider, Innovation. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ Ferris Jabr for Scientific American. 11 March 2013. Will cloning ever saved endangered species?

- ^ Heidi B. Perlman (8 October 2000). "Scientists Close on Extinct Cloning". The Washington Post. Associated Press.

- ISBN 0-7425-3408-1.

- ^ Holloway, Grant (28 May 2002). "Cloning to revive extinct species". CNN.com.

- ^ Gray, Richard; Dobson, Roger (31 January 2009). "Extinct ibex is resurrected by cloning". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 1 February 2009.

- ^ "Scientists 'to clone mammoth'". BBC News. 18 August 2003.

- ^ "BBC News". Bbc.co.uk. 7 December 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Когда вернутся мамонты" ("When the Mammoths Return"), February 5, 2015 (retrieved September 6, 2015)

- National Geographic. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "Long Now Foundation, Revive and Restore Project".

- ^ "Generations of Cloned Mice With Normal Lifespans Created: 25th Generation and Counting". Science Daily. 7 March 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ISBN 978-184831-347-7.

- ^ "TIME Magazine – U.S. Edition – Vol. 142 No. 19". 8 November 1993. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Today The Sheep..." Newsweek. 9 March 1997. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ Huxley, Aldous; "Brave New World and Brave New World Revisited"; p. 19; HarperPerennial, 2005.

- ISBN 9788126910366. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ISBN 9780415974608.

- ^ planktonrules (17 December 1973). "Sleeper (1973)". IMDb. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ISBN 0199673969. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ISBN 9781476604541. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ISBN 9781592592050. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ISBN 9780812697254. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- JSTOR 3527566.

- ^ "Yvonne A. De La Cruz ''Science Fiction Storytelling and Identity: Seeing the Human Through Android Eyes''" (PDF). Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ^ "Uma Thurman, Rhys Ifans and Tom Wilkinson star in two plays for BBC Two" (Press release). BBC. 19 June 2008. Retrieved 9 September 2008.

- ^ "Review of Bunshin".

- ^ foreverbounds. "Orphan Black (TV Series 2013– )". IMDb. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Banville, John (10 October 2004). "'The Double': The Tears of a Clone". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ Christian Lee Pyle (CLPyle) (12 October 1978). "The Boys from Brazil (1978)". IMDb. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ISBN 9780761328025. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ISBN 9781480342958. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ISBN 9781442234819. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ISBN 9780786471812. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ compel_bast (15 August 2008). "Star Wars: The Clone Wars (2008)". IMDb. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ espenshade55 (11 February 2011). "Never Let Me Go (2010)". IMDb. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Island (2005)". IMDb. 22 July 2005. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ larry-411 (17 July 2009). "Moon (2009)". IMDb. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Technology News – 2017 Innovations and Future Tech".

External links

- "Cloning". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Cloning Fact Sheet from Human Genome Project Information website.

- 'Cloning' Freeview video by the Vega Science Trust and the BBC/OU

- Cloning in Focus, an accessible and comprehensive look at cloning research from the University of Utah's Genetic Science Learning Center

- Click and Clone. Try it yourself in the virtual mouse cloning laboratory, from the University of Utah's Genetic Science Learning Center

- "Cloning Addendum: A statement on the cloning report issues by the President's Council on Bioethics," The National Review, 15 July 2002 8:45am