Stanisławów Ghetto

| Stanisławów Ghetto | |

|---|---|

Tempel Synagogue in Stanislavov before World War II | |

Stanisławów location during German occupied Poland today Ivano-Frankivsk, Western Ukraine | |

| Incident type | Imprisonment, slave labor, mass killing |

| Organizations | SS |

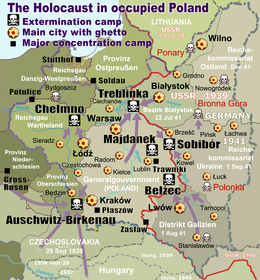

| Camp | Belzec (see map) |

| Victims | 20,000 Jews[1] and 10,000–12,000 before the Ghetto was set up, in Bloody Sunday massacre |

Stanisławów Ghetto (

On 12 October 1941, during the so-called Bloody Sunday, some 10,000–12,000[3] Jews were shot into mass graves at the Jewish cemetery by the German uniformed SS-men from SIPO and Order Police battalions assisted by the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police. Dr. Tenenbaum of the Judenrat refused the offer of exemption and was killed along with the others.[1] Two months after that, the ghetto was established officially for the 20,000 Jews still remaining, and sealed off with walls on 20 December 1941. Over a year later, in February 1943, the Ghetto was officially closed, when no more Jews were held in it.[1]

Historical background

The Polish

During the 1939 invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, the province was captured by the Red Army in September 1939. The Soviet NKVD crimes committed against the local population included the last minute massacre of 2,500 political prisoners in the city,[6] Ukrainian, Polish, and Jewish alike,[7] just before the Nazi occupation of Stanislavov.[8][9] Women with dozens of children were shot by the Soviets at the secluded Dem'ianiv Laz ravine outside the city, among at least 524 victims forced to dig their own mass grave.[6][10]

Nazi atrocities

There were more than 50,000 Jews in Stanisławów and surrounding countryside when it was occupied by the Hungarian army on 2 July 1941.[7] The Germans arrived on 26 July.[3] On the same day, the Gestapo detachment ordered a Judenrat established in the city.[11] It was headed by Israel Seibald.[1] On 1 August 1941, Galicia became the fifth district of the General Government. A day later, Poles and Jews of the intelligentsia were ordered to report to the police under the guise of "registering" for placement. Of the eight hundred men who came, six hundred were transported by SIPO to the forest called Czarny Las, near Pawełcze village (Pawelce),[12][13] and murdered in secrecy.[14] Families (80% Jewish)[15] were not informed, and continued sending parcels for them.[16]

The command of Stanisławów was taken over by an

Bloody Sunday massacre

On 12 October 1941 at the orders of

The Bloody Sunday massacre of 12 October 1941 was the single largest massacre of Polish Jews perpetrated by the uniformed police in the

The ghetto

On 20 December 1941 the Stanisławów Ghetto was set up officially, and closed from the outside.[1] Walls were built (with three gates), and the windows facing out boarded up. Some 20,000 Jews were crammed there into a little space. Rationing was enforced, with insufficient food, and workshops set up to support the German war effort. Over the winter and until July 1942 most extrajudicial killings were carried out in Rudolf's Mill (Rudolfsmühle).[1] From August 1942 onward the courtyard of the SiPo headquarters was used for that. On 22 August 1942, the Nazis held the reprisal Aktion for the murder of a Ukrainian collaborator, which they blamed on a Jew. More than 1,000 Jews were rounded up and shot at the cemetery. The leader of the Jewish council, Mordechai Goldstein, was hanged in public, along with 20 members of the Jewish Ghetto Police. Before taking them to the SiPo headquarters, policemen raped Jewish girls and women.[1]

The Ghetto was reduced in size after the German and Ukrainian raid of 31 March 1942, and the burning of homes, in punishment for the council's noncompliance with the first deportation action.

Just before the liquidation of the ghetto, a group of Jewish insurgents managed to escape. They formed a partisan unit called "Pantelaria" active on the outskirts of Stanisławów. The two commanders were young Anda Luft pregnant with her daughter Pantelaria (born in the forest),[27] and Oskar Friedlender. Their greatest accomplishment was the ambush and execution of the German chief of police named Tausch. The group was attacked and destroyed by the Nazis in mid winter 1943–44. Anda and her new baby girl were killed.[7]

There were rescue attempts during the ghetto liquidation. When the Jehovah's Witnesses learned that the Nazis planned to murder all Jews in the city, they organized an escape from the ghetto for a Jewish woman and her two daughters who later became Witnesses. They hid these Jewish women throughout the entire period of the war.[28] Among the Christian Poles bestowed with the honour of Righteous Among the Nations were members of the Ciszewski family who hid in their home eleven Jews escaping deportation to Belzec extermination camp in September 1942. All survived.[29] The Gawrych family hid five Jews until 8 March 1943, when they were raided by German policeman. Four Jews were shot and killed, and one (Szpinger) managed to escape. Jan Gawrych was arrested and subsequently was tortured and murdered.[30] The Soviet army reached the city on 27 July 1944. Hidden by rescuers, there were about 100 Jewish Holocaust survivors liberated. In total about 1,500 Jews from Stanisławów survived the war elsewhere.[1]

Aftermath

The commander of Stanisławów during the Bloody Sunday massacre

Following World War II, at the insistence of Joseph Stalin during

Footnotes

- a. SS).

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Andrea Löw, USHMM (10 June 2013). "Stanislawów (now Ivano-Frankivsk)". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

From The USHMM Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ISBN 0-271-02308-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Dieter Pohl. Hans Krueger and the Murder of the Jews in the Stanislawow Region (Galicia) (PDF file from Yad Vashem.org). pp. 12/13, 17/18, 21.

It is impossible to determine what Krueger's exact responsibility was in connection with "Bloody Sunday" [massacre of 12 October 1941]. It is clear that a massacre of such proportions under German civil administration was virtually unprecedented.

- ^ "The 1931 GUS Census. District of Stanisławów". Kresy.co.uk. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ Sejm, Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych (Poland's Internet archive of State published documents). Dz.U. 1924 nr 102 poz. 937. (in Polish)

- ^ a b Robert Nodzewski, "Demianów Łaz" IV Rozbiór Polski, 1939. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d Grzegorz Rąkowski (2007). "Historia Stanisławowa". Przewodnik po Czarnohorze i Stanisławowie (in Polish). Stanislawow.net. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- ISBN 1-57181-882-0– via Google Books preview.

- ^ Brian Crozier, Remembering Katyn | Hoover Institution. Archived 24 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine 30 April 2000; Stanford University. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ Soviet 1941 massacre at Dem'ianiv Laz. Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Memorial Society (memorial.kiev.ua). Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ Muzeum Historii Żydów PolskichPOLIN. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ a b PWL. "Mord w Czarnym Lesie (Murder in the Black Forest)". Województwo Stanisławowskie. Historia. PWL-Społeczna organizacja kresowa. Archived from the original on 27 November 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ a b Tadeusz Kamiński, Tajemnica Czarnego Lasu (The Black Forest Secret, Internet Archive). Publisher: Cracovia Leopolis, Kraków, 2000. Book excerpts.

- ^ Dieter Pohl 1998, p. 6/24.

- )

- ^ a b c Holocaust Encyclopedia – Stanisławów. 1941–44: Stanislau, Distrikt Galizien. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ Symposium Presentations (September 2005). "The Holocaust and [German] Colonialism in Ukraine: A Case Study" (PDF). The Holocaust in the Soviet Union. The Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 15, 18–19, 20 in current document of 1/154. Archived from the original on 16 August 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Tadeusz Olszański (4 November 2009). "Wkracza gestapo". Opowieści z rodzinnego grodu. Tygodnik Polityka. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8032-0392-1. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- )

- ^ George Eisen, Tamás Stark (2013). The 1941 Galician Deportation (PDF). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 215 (9/35 in PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

More than 10,000 Jews, including 2,000 Hungarian Jews [the so-called "Galicianer" Jews deported out of Hungary], perished on that day — as it happened, on the last day of the Jewish festival of Sukkoth (Hoshana Rabbah). SS-Hauptsturmführer (Captain) Hans Krüger orchestrated the massacre, aided by Ukrainian collaborators and Reserve Police Battalion 133. Notably, Krüger had at his disposal a Volksdeutsche unit, recruited from Hungary, that routinely participated in exterminations.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ McKinley von Theme, 1941: 12 Oktober – Erschiessung in Stanislawow. Archived 11 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine ShoaPortalVienna 2014, den opfern zum gedenken. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ^ H.M.C., Timeline of Jewish Persecution: 1941. October 12: Bloody Sunday. Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- Museum of the History of Polish Jews. pp. 6–7. Archived from the originalon 23 October 2014. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- Browning, Christopher R. (1998) [1992]. Arrival in Poland (PDF file, direct download 7.91 MB complete). Penguin Books. pp. 135–136, 141–142. Retrieved 5 December 2014.)

Also: PDF cache archived by WebCite.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); External link in|quote= - ^ Struan Robertson (2013). "The genocidal missions of Reserve Police Battalion 101 in the General Government (Poland) 1942–1943". Hamburg Police Battalions during the Second World War. Regionalen Rechenzentrum der Universität Hamburg. Archived from the original on 22 February 2008. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Agnieszka Zagner, Tadeusz Olszański, "Życie kresowe" (PDF file, direct download 9.51 MB) Żydowskie Muzeum Galicja w Krakowie. "W tym miesiącu". Słowo Żydowskie Nr 6 (448) 2009, p. 18.

- ^ 2002 Yearbook of Jehovah's Witnesses. — N.Y.: Watchtower, 2001; p. 143.

- Museum of the History of Polish Jews. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ "Gawrych FAMILY". db.yadvashem.org. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ Albert Norden, "Krüger, Hans: Ein Blutrichter Hitlers" at www.braunbuch.de Braunbuch. War and Nazi Criminals in the Federal Republic.

- ^ Bund der Vertriebenen, Hans Krüger, der 1964 BdV-Präsident zurücktreten musste. Archived 10 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine 20 August 2006. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

Further reading

- OCLC 768801015.

Source: Yad Vashem Studies, Vol. 26, Jerusalem 1998, pp. 239–265.

- Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich, Sprawiedliwi wśród Narodów Świata. Przywracanie Pamięci. Odznaczeni. (in Polish)

- Weiner, Rebecca. Virtual Jewish History Tour

- Dr. Mordecai Paldiel, "83.7 KB".

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help)83.7 KB Yad Vashem, The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority. - Jason Hallgarten, The Rabka Four. Instruments of Genocide and Grand Larceny (Poland) by Robin O'Neil (2011) Chapter 7: Hans Krueger in Stanislawow, Kolomyja and District. Yizkor Book Project.

- G. L. Esterson, Extermination of the Jews in Galicia by Robin O'Neil Chapter 6: Kolomyja and District Transports to Belzec. Yizkor Book Project 2009.